- capitalism is dominated by the rich, who set the political agenda;

- capitalism leads to growing inequality;

- capitalism promotes selfishness and greed; and

- capitalism leads to monopolies.

Virtual spaces for learning and collaboration

Today, I’ve been doing a UCL short course. As we were coming back from a break, we were discussing the lack of ‘embodiedness’ in virtual interactions. This reminded me of experiments with different platforms that WAO did during the pandemic.

This post by Alja from Tethix is prompted by a challenge-based learning platform that I took part in last year. They’re focusing on tech ethics (hence the name) and their approach was great. It was just that the tools got in the way to some extent.

I think, after reading this, it’s time to experiment again with some of the tools mentioned in the post. Sometimes you do need a sense of play and feel like you’re connected in ways that go beyond small boxes on a screen.

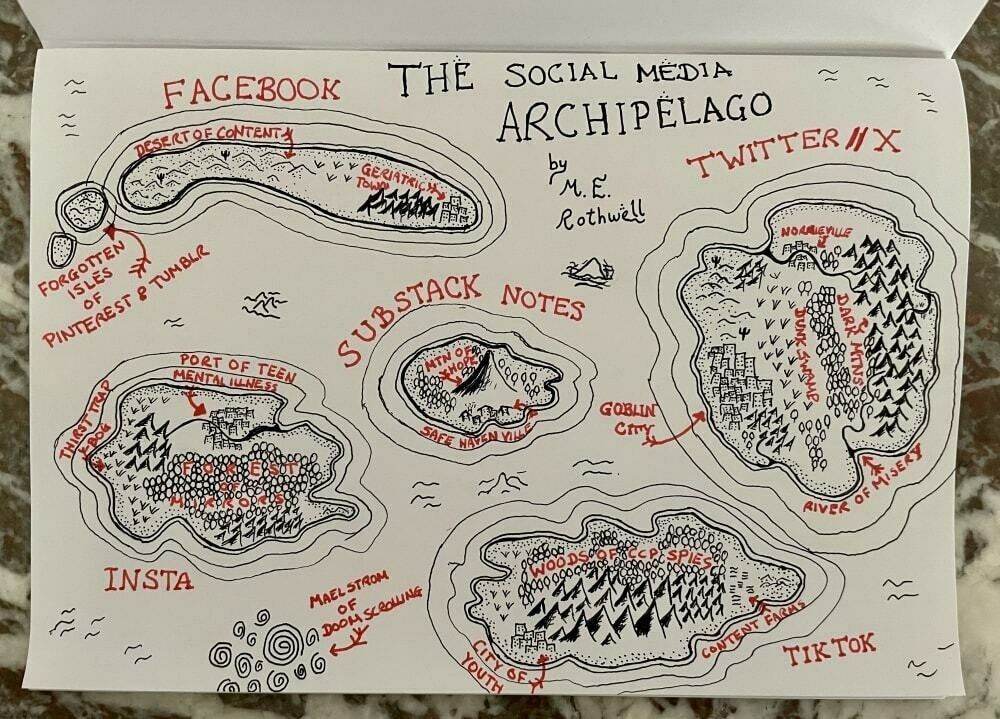

The Tethix Archipelago emerged from the Challenge Based Learning pilot we did in March last year. For the pilot, we designed a unique collaborative online learning experience in tech ethics and used Mural collaborative whiteboards and visual storytelling to situate the learning journey in a fictional world: the Tethix Archipelago. The Archipelago consists of four islands that emerged from the four essentials skills of the Challenge Based Learning journey: collaboration, exploration, practice, and reflection.Source: Welcome to the Tethix Archipelago | TethixMural turned out to be a great tool for collaboration and live session guidance, but it didn’t really convey a sense of place. Clicking on a link in a Mural to visit the next leg of your journey just doesn’t feel like traveling, especially when you’re trapped in the same little Zoom box during every live session.

So we started exploring tools that could help us convey a sense of space and discovered Gather and WorkAdventure, among others. These tools offer two-dimensional virtual collaborative spaces where you can walk around a space with your avatar and have proximity-based conversations by using your microphone and camera.

[…]

You might be thinking: this is cute and all, but is this Archipelago all games and play? Well, playfulness is a big part of why we’re experimenting with these game-like worlds; we know that play helps us learn better and can unlock our imagination. But there’s much more to it than just millennial nostalgia for pixel graphics.

As already mentioned, Gather allows us to build a sense of place, both inside rooms and between them. And a sense of place helps with learning and memory encoding. Historical records show ancient Greeks using the method of loci or memory palaces, a technique for improving memory encoding and retrieval, and humans have been developing other mnemonic techniques based on spatial relationship for much longer than that. We’re physical beings, uniquely equipped to understand space, whether physical or represented by pixels.

This isn't working. Can we talk about that?

Thankfully, there’s no-one calling me back into the office. But this post is about people who are being recalled — as well as those working in sub-optimal remote settings.

This post suggests that the phrase “this isn’t working” should be viewed as an invitation for dialogue rather than a threat, arguing that open communication is crucial for things inadequate in the workplace.

The Future of Work conversation is full of rejected gifts. We've seen bosses throw "this isn't working" back in employees' faces as "entitlement." As "millennials." As "no one wants to work anymore." We've seen employees throw it back in their CEO's face, too, as "outdated." Or "boomers." Or "something something commercial real estate." As far as we can tell, that point-scoring hasn't gotten us any closer to the future we're all trying to build.Source: Sorry I’m getting kicked out of this room | Raw Signal GroupWe know that everyone’s sick of constantly redesigning the rules of work. There’s this revisionist nostalgia for, in some quarters, 2019. And in others, 2021. We know that some of you have built systems here in 2023 that are working for you, and you would like them to please just stay put for a goddamned minute. We get that. But when someone tells you that those systems aren’t working for them, shouting them down won’t give you the peace and quiet you want.

[…]

By all means, read what other orgs are doing. Maybe there are things you can learn from what Apple does, or Google, or Smuckers. But there’s no shortcut around the conversation. Every sales person, fundraiser, marketer, product leader, and designer will tell you the same thing. You have to talk to people to know if you’re actually reaching them. To know if any of your solutions actually solve the problem.

Constructs, meta-constructs, and shared cognitive spaces

Posts like this one by Venkatesh Rao are like catnip to me. He explores the concept of the ‘real world’ as a construct shaped by collective human beliefs and values, arguing that it is, of course, anthropocentric and inherently absurd.

All worlds created by humans, such as fandoms and nationalisms, have more or less consequence in shaping the ‘real world’. In other words, there are constructs which serve to help shape the meta-construct. This, in essence, is a shared cognitive space for humans.

Well worth reading if you’re in the mood to question the nature of reality, explore the power of collective belief, and ponder the transient nature of what we consider to be ‘real’. It’s a complex examination of how human perception shapes the world we live in, and how that world, in turn, shapes us.

Accounting for consciously shared worlds like religions, fandoms, and nationalisms, as well as commonalities that arise from obvious and lazy lines of thought or imitation, there are perhaps a few thousand to tens of thousands of non-trivial distinct inhabited worlds out there. Of these, perhaps a few hundred are significant enough to require accounting for in any analysis. The rest are, at best, butterflies flapping in the chaotic weather-systems of history, hoping to cause hurricanes.Source: This is the New Real World | Venkatesh RaoOf the few hundred that are significant, perhaps a couple of dozen matter strongly, and perhaps a dozen matter visibly, the other dozen being comprised of various sorts of black or gray swans lurking in the margins of globally recognized consequentiality.

This then, is the “real” world — the dozen or so worlds that visibly matter in shaping the context of all our lives, with common knowledge of such shaping constituting a non-trivial part of the visibly mattering. The consequentiality of the real world is partly a self-fulfilling prophecy of its own reality. Something that can play the rule of truth. For a while.

[…]

The real world, in other words, is a fragile, unreliable, dubious, borderline incoherent, unsatisfying house of cards destined to die. Yet, while it lives and reigns, it is an all-consuming, all-dominating thing. A thing that can seem extraordinarily real compared to any more fragile, value-based private delusions we may harbor. To the point that we typically refer to it unironically as the real world, to be contrasted with self-indulgent fantasies, and characterize belief in it as pragmatism rather than just a grittier delusion.

Image: Marcus Spiske

Research shows people in most countries are anti-capitalist

I came across this via fellow Sunderland AFC supporter Andrew Curry’s Just Two Things newsletter. We also share similar political views, so I share his delight that this journal article from a right-wing thinktank does the opposite of what they were evidently setting out to achieve.

The article presents findings from a global survey on attitudes towards capitalism, revealing that pro-capitalist views are rare and mostly found in six countries. Bizarrely, and seemingly clutching at straws, the research found anti-capitalist views often correlate with conspiracy thinking and negative attitudes towards the rich.

You’re not paranoid if they’re out to get you, and it’s not a conspiracy if capitalism really does favour the 0.1%.

In only seven of 34 countries – Poland, the United States, the Czech Republic, Japan, Argentina, South Korea, and Sweden – does a positive attitude towards economic freedom clearly prevail. Including the word ‘capitalism’ reduces this to just six of 34 countries, namely Poland, the United States, the Czech Republic, Japan, Nigeria and South Korea. In most countries, anti-capitalist sentiment dominates.Source: Attitudes towards capitalism in 34 countries on five continents | Economic AffairsWhat is it exactly that bothers people about capitalism? If you look at the survey’s overall conclusions, it is – in this order – primarily the opinion that:

Not surprisingly, anti-capitalism is most pronounced among those on the left of the political spectrum and the strongest pro-capitalists are to be found to the right of centre. But while in some countries the formula is ‘the more right-wing, the more supportive of capitalism’, there are more countries in which moderate right-wingers are somewhat more supportive of capitalism than those on the far right of the political spectrum.

What's good for us is also good for the planet

I came across this via Dense Discovery, which is one of a number of additional newsletters to which I would recommend Thought Shrapnel readers subscribe.

In this article, Erin Remblance shows how modern lifestyles, particularly in wealthy nations, have led to a loss of human connection and an increase in mental health issues. She suggests that the shift from community-oriented activities to individualistic, consumer-driven behaviour has not only harmed our well-being but also contributed to the climate emergency.

The solution? Returning to simpler, more sustainable ways of living that focus on human connection and creativity. By becoming creators rather than mere consumers we can improve our mental health and simultaneously benefit the planet.

One of the top 5 regrets of the dying is that they wished that they hadn’t worked so hard. Another is that they wished they’d been brave enough to pursue the life they’d really dreamed of, without worrying about what others thought; that they’d had the courage to do the things that made them truly happy. Which is ironic, really, because according to the 18th century economist and philosopher, Adam Smith, wealth is something that is “desired, not for the material satisfaction that it brings, but because it is desired by others”. People are getting to the end of their lives regretting that they worked so hard – often to accumulate wealth so that others could envy it – wishing that instead they had pursued things that truly made them happy regardless of what people thought. What a lesson we could learn from these people’s dying realisations.Source: We are not supposed to live like this | Erin Remblance[…]

Reducing our consumption is of course important for the health of the planet, but what if one way to do this is by becoming producers, or creators, ourselves? Rediscovering what our human-energy – an abundantly available energy we seem to be using increasingly less of – can achieve, something we once innately drew upon, now buried deep within us as fossil-fuelled energy has overtaken our lives. There’s a clear link here to actions that will mitigate climate change: walking, cycling, growing our own food, and other low-tech solutions such as repairing and fostering community that encourages “social connections … rather than fostering the hyper-individualism encouraged by resource-hungry digital devices.”

[…]

We are not supposed to live like this, and it shows. We can see it in the deterioration of mental and physical health of people in so called ‘wealthy’ nations, in the exploitation of people in the Global South, and we can see it in the planetary-wide ecological crisis we face. What if, in trying to heal ourselves, we also begin to heal the planet? Because, in a wonderful turn of events, it would seem that what is good for us, is good for the planet too.

The Empty Boat

This was cited in something I read last week and I thought it was worth making it easy for me to re-find. There are plenty of philosophers, including Aristotle, who talk about the difference between the way we treat animate and inanimate objects, but none put it so eloquently as Chuang Tzu.

If a man is crossing a riverSource: The Empty Boat by Chuang Tzu | Daily ZenAnd an empty boat collides with his own skiff,

Even though he be a bad-tempered man

He will not become very angry.

But if he sees a man in the boat,

He will shout at him to steer clear.

If the shout is not heard, he will shout again,

And yet again, and begin cursing.

And all because there is somebody in the boat.

Yet if the boat were empty.

He would not be shouting, and not angry.

Maybe it makes sense to talk to plants after all

Although I’ve alluded to talking to plants in the title for this post, the interesting thing here is that research shows they can sense vibrations made by insects like caterpillars. This allows the plants to prepare for an attack by producing defensive chemicals.

Some research suggests that plants can even detect the sound of water, which could have implications for sewer systems. The findings open up possibilities for using sound-based interventions in agriculture, such as drones equipped with speakers to warn crops of impending pest attacks.

Plants have been evolving alongside the insects that pollinate them and eat them for hundreds of millions of years. With that in mind, Heidi Appel, a botanist now at the University of Houston, and Reginald Cocroft, an entomologist at the University of Missouri, wondered if plants might be sensitive to the sounds made by the animals with which they most often interact. The researchers recorded the vibrations made by certain species of caterpillar as they chewed on leaves. These vibrations are not powerful enough to produce sound waves in the air. But they are able to travel across leaves and branches, and even to neighbouring plants if their foliage touches.Source: Plants don’t have ears. But they can still detect sound | The EconomistThe researchers then exposed Thale cress—the plant biologist’s version of the laboratory mouse—to the recorded vibrations while no caterpillars were actually present. Later, they put real caterpillars on the plants to see if exposure had led them to prepare for an insect attack. The results were striking. Leaves that had been exposed had significantly higher levels of defensive chemicals like glucosinolates and anthocyanins, making them much harder for the caterpillars to eat. Leaves on control plants that had not been exposed to vibrations showed no such response. Other sorts of vibration—caused by the wind, for instance, or other insects that do not eat leaves—had no effect.

[…]

The research may have practical consequences, too. “Drones armed with speakers and the right audio files could warn crops to act when pests are detected but not yet widespread,” says Dr Cocroft. Unlike chemical pesticides, sound waves leave no toxic residue. With the help of weather forecasts, the system could even be used to prepare crops for cold snaps.

[…]

Farmers monitor the health of their crops by eye. (Mosaic virus, for instance, is so named because of the mottled pattern produced on the leaves of suffering plants.) That can be hard to do properly over an entire field. But if plants are broadcasting auditory indicators of distress, then wiring a field with microphones might help farmers keep an ear out for trouble.

Noise and working from home

I’ve worked from home for the last eleven years. For the last nine years, I’ve lived near the middle of a market town in the north east of England. You wouldn’t believe the amount of noise.

As respondents in this Hacker News thread comment, you kind of get used to it, and also work around particularly loud noise. However, the struggle is real and now that my wife and I both work from home it’s a factor in us moving.

I’d second the opinion of the commenter I’ve quoted below about getting headphones with at least two levels of noise cancellation. I bought some Sony WH-CH720N cans when they started building behind my home office and they’ve been a godsend.

My personal experience as a big-city dweller who has also worked for prolonged stints in suburban and very rural places is that the suburban version of this problem can really be the worst of both worlds.Source: Ask HN: How do you deal with never ending noise and distraction WFH? | Hacker NewsWhen I’m vising my parents in the suburbs… its generally quiet, but that one leaf blower 4 doors down or the one garbage truck crawling down the block suddenly becomes the only thing I can focus on. The noises are infrequent and jarring when they occur.

When I’m at home in my city apartment, the background noise is truly constant - it forms a canvas, nothing really jumps out and therefore the level of what it takes to make a distraction is a lot higher.

My practical advice is to explore headphones with passive noise isolation instead of active noise cancelling. The passive isolation is pretty foolproof, even with sudden or extreme changes in background noise content that the active noise cancelling sometimes takes a moment to adjust to (or perhaps try something like working in a coffee shop for an hour to get the other extreme and reset: write emails where distraction is more OK, come home to the relative quiet of the home office for focus time. I’ve also found even a change of scenery can get me into the zone regardless of what is going on environmentally)

Image: Pexels

Shrinkflation, sizes, and shaming

I’d be surprised if ‘shrinkflation’ isn’t word of the year for 2023. For those unaware, it’s the reason why prices for some products have stayed the same while their size decreases.

This article is about Carrefour, one of Team Belshaw’s favourite overseas supermarkets. They’ve added warnings on shelves to “shame” brands. The thing is, as this thread from Mario Zechner shows, it’s not as if supermarkets aren’t in the price fixing game. Also, as I wrote about recently, stores are essentially panopticons.

While I’m on the subject, you might be interested in this crowdsourced website which tracks the differences in size of packs of everything from toothpaste to shortbread biscuits.

The French supermarket chain Carrefour has put labels on its shelves this week warning shoppers of “shrinkflation”, the phenomenon where manufacturers reduce pack sizes rather than increase prices.Source: Carrefour puts ‘shrinkflation’ price warnings on food to shame brands | The GuardianIt has slapped price warnings on products from Lindt chocolates to Lipton iced tea to pressure top consumer goods suppliers Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever to tackle the issue in advance of much-anticipated contract talks.

[…]

Carrefour has marked 26 products in its stores in France with the labels, which say: “This product has seen its volume or weight fall and the effective price from the supplier rise.”

For example, Carrefour said a bottle of sugar-free peach-flavoured Lipton iced tea, produced by PepsiCo, shrank to 1.25 litres (0.33 gallon) from 1.5 litres, resulting in a 40% effective increase in the price a litre.

Good news on Covid treatments

Well this is promising. Researchers have identified a critical weakness in COVID-19 in its reliance on specific human proteins for replication. The virus has an “N protein” which needs human cells to properly package its genome and propagate. Apparently, blocking this interaction could prevent the virus from infecting human cells.

Right now, the most effective treatment for COVID is Paxlovid, which is only effective within three days of infection. This new discovery could lead to medications useful at all stages of infection and potentially pave the way for a new class of antivirals useful against other viruses like flu, RSV, and Ebola.

COVID takes advantage of a human post-translation process called SUMOylation, which directs the virus’ N protein to the right location for packaging its genome after infecting human cells. Once in the right place, the protein can begin putting copies of its genes into new infectious virus particles, invading more of our cells, and making us sicker.Source: Scientists uncover COVID’s weakness | UC Riverside News“In the wrong location, the virus cannot infect us,” said Quanqing Zhang, co-author of the new study and manager of the proteomics core laboratory at UCR’s Institute for Integrative Genome Biology.

[…]

This paper shows that COVID depends on SUMOylation proteins, just as the flu does. Blocking access to the human proteins would allow our immune systems to kill the virus.

Currently the most effective treatment for COVID is Paxlovid, which inhibits virus replication. But patients need to take it within three days following infection. “If you take it after that it won’t be so effective,” Liao said. “A new medication based on this discovery would be useful to patients at all stages of infection.”

Navigating the landscape of Digital and Media Literacy

The report from Tactical Tech focuses on Digital Media Literacy (DML), exploring its complexities and the challenges associated with how it’s assessed. It delves into the role of teachers and educators, hopefully once and for all dismissing the notion of “digital natives” and “digital non-natives”. The report emphasises that both teachers and students bring unique perspectives to digital learning environments: teachers may offer critical thinking skills, while students may be more comfortable with digital tools.

This commissioned research report is a continuation of the Media Literacy Case for Educators project, which was introduced in April 2023 in the article: Media Literacy Case for Educators: Empowering Educators to Lead Media Literacy Initiatives in Europe and referenced in: An Assessment of the Needs of Educators and Youth in Europe for a Digital and Media Literacy Education Intervention.Two phases of exploration have been conducted, involving two rounds of desk research. The result of the second phase can be seen in the annotated bibliography included at the end of this report. Recommendations which resulted from the research include: combine methods and make learning fun; use evaluation and other key elements in the curriculum. Additional observations and considerations which require further exploration include: give attention to teachers’ and educators’ skills; and develop “patchwork blankets” and alliances.Source: Digital and Media Literacy Education: Navigating an Ever-Evolving Landscape | Tactical Tech

Ducks, prompting, and LLMs

Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT don’t allow you to get certain information. Think things like how to make a bomb, how to kill people and dispose of the body. Generally stuff that we don’t want at people’s fingertips.

Some things, though, might be prohibited because of commercial reasons rather than moral ones. So it’s important that we know how to theoretically get around such prohibitions.

This website uses the slightly comical example of asking an LLM how to take ducks home from the park. Interestingly, the ‘Hindi ranger step-by-step approach’ yielded the best results. That is to say that prompting it in a different language led to different results than in English.

Language models, whatever. Maybe they can write code or summarize text or regurgitate copyrighted stuff. But… can you take ducks home from the park? If you ask models how to do that, they often refuse to tell you. So I asked six different models in 16 different ways.Source: Can I take ducks home from the park?

The supermarket is a panopticon

My son’s now old enough to get ‘loyalty cards’ for supermarkets, coffee shops, and places to eat. He thinks this is great: free drinks! money off vouchers! What’s not to like? On a recent car journey, I explained why the only loyalty card I use is the one for the Co-op, and introduced him to the murky world of data brokers.

In this article, Ian Bogost writes in The Atlantic about the extensive data collection by retailers to personalise marketing. This not only predicts but also influences consumer behaviour, raising ethical concerns about the erosion of privacy and democratic ideals. Bogost argues that this data-driven approach shifts the power balance, allowing companies to manipulate consumer preferences.

In marketing, segmentation refers to the process of dividing customers into different groups, in order to make appeals to them based on shared characteristics. Though always somewhat artificial, segments used to correspond with real categories or identities—soccer moms, say, or gamers. Over decades, these segments have become ever smaller and more precise, and now retailers have enough data to create a segment just for you. And not even just for you, but for you right now: They customize marketing messages to unique individuals at distinct moments in time.Source: You Should Worry About the Data Retailers Collect About You | The AtlanticYou might be thinking, Who cares? If stores can offer the best deals on the most relevant products to me, then let them do it. But you don’t even know which products are relevant anymore. Customizing offerings and prices to ever-smaller segments of customers works; it causes people to alter their shopping behavior to the benefit of the stores and their data-greedy machines. It gives retailers the ability, in other words, to use your private information to separate you from your money. The reason to worry about the erosion of retail privacy isn’t only because stores might discover or reveal your secrets based on the data they collect about you. It’s that they can use that data to influence purchasing so effectively that they’re rewiring your desires.

[…]

Ordinary people may not realize just how much offline information is collected and aggregated by the shopping industry rather than the tech industry. In fact, the two work together to erode our privacy effectively, discreetly, and thoroughly. Data gleaned from brick-and-mortar retailers get combined with data gleaned from online retailers to build ever-more detailed consumer profiles, with the intention of selling more things, online and in person—and to sell ads to sell those things, a process in which those data meet up with all the other information big Tech companies such as Google and Facebook have on you.“Retailing,” Joe Turow told me, “is the place where a lot of tech gets used and monetized.” The tech industry is largely the ad-tech industry. That makes a lot of data retail data. “There are a lot of companies doing horrendous things with your data, and people use them all the time, because they’re not on the public radar.” The supermarket, in other words, is a panopticon just the same as the social network.

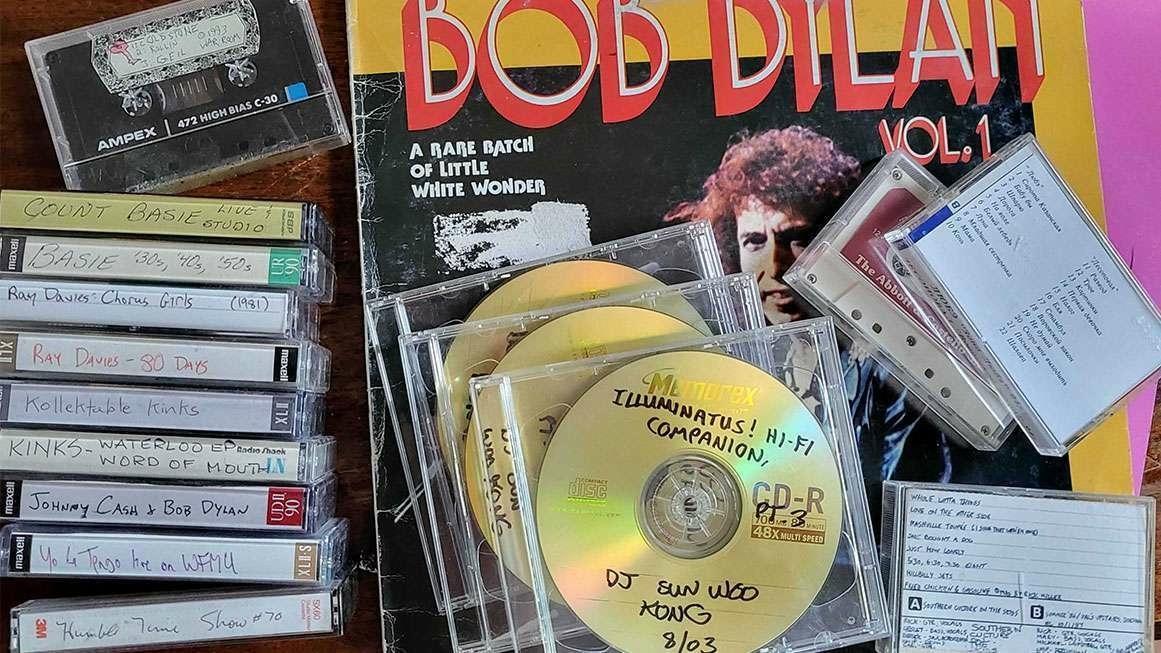

Piracy and the art of cultural archiving

Shortly before Daft Punk’s album Discovery was released, I managed to download a version of it which must have been exfiltrated from the studio. It was subtly different to the version that was released and, to be honest, I preferred it. Sadly, I’ve long since lost the MP3s, and the chance of me finding anything other than the official version these days is minimal.

This article is about the preservation of music, movies, and books. What copyright maximalists don’t realise is that piracy is actually amazing at ensuring that cultural diversity flourishes and is preserved. It’s definitely worth a read.

(It’s also interesting to me how this intersects what I posted earlier about AI-generated music and fandom, because both intersect with ‘official’ narratives and our current understanding of copyright.)

"Your local bookseller cannot creep into your home in the middle of the night and reclaim the contents of your bookshelf," the legal scholars Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz observe in their 2016 book The End of Ownership. "But Amazon exercises a very different kind of practical power over your digital library. Your Kindle runs software written by Amazon, and it features a persistent network connection. That means Amazon can send it instructions—to delete a book or even replace it with a new version—without any intervention from you." The potential for mischief was clear as early as 2009, when someone started selling bootleg Kindle editions of George Orwell's 1984 and Amazon reacted by dispatching even some purchased copies to the memory hole.Source: Online Outlaws Preserve the History of Music, Movies, and Books | ReasonThe fearful mood intensifies whenever politics enters the picture. When books by Agatha Christie, Roald Dahl, and other long-dead authors were reedited to reflect what are said to be “contemporary sensitivities,” many e-books were automatically updated even for readers who had bought them long before. During the George Floyd protests of 2020, several streaming services, unable to stop the abusive policing that set off the unrest, decided instead to edit or eliminate TV episodes where characters appeared in blackface. (This wasn’t an anti-racist gesture so much as a cargo-cult copy of an anti-racist gesture—an elaborate imitation built without figuring out the functions of the component parts—and so it mostly affected shows that had presented blackface with obvious disapproval.) Several songs with words that might offend listeners have gone missing from Spotify or (as with Lizzo’s “Grrrls,” which originally included the term spaz) were replaced with new versions.

Every time news breaks of one of these deletions, a refrain echoes online: Buy physical media! The internet is too impermanent, the argument goes: The real cultural cornucopia was in the outside world.

As is often the case with nostalgia, this leaves out a lot. We still have access to far more media than we did in the days before the mass internet. Yes, this includes that politically controversial material: It takes less than a minute to dig up the unredacted version of “Grrrls” on YouTube (just search for lizzo grrrls spaz), and it’s not hard to find material that was withdrawn from circulation long before the internet era. (I’m told the ’90s were a less politically correct time than today, but back then you needed to track down a bootleg DVD or videotape if you were curious about Song of the South. Now it’s posted on the Internet Archive.) It’s too easy to take the internet’s riches for granted and to forget how much was inaccessible just a few decades ago.

But while we shouldn’t want to return to those pre-web days, there’s something to be said for that online-offline hybrid space where my old tape-trading network dwelled—if not as a world to recreate, then as a way to think about cultural preservation. And there’s something to be said for the bootleggers and pirates. Whether or not they mean to do it, they’re salvaging pieces of our heritage.

Greatest films of all time?

I confess to only having watched one of the top 10 films on this list, which is put together mainly be critics and people who work in the film industry. Must rectify that.

On the other hand, I have watched seven of the top 10 films on the IMDB top 250 list…

In 1952, the Sight and Sound team had the novel idea of asking critics to name the greatest films of all time. The tradition became decennial, increasing in size and prestige as the decades passed.Source: The Greatest Films of All Time | BFIThe Sight and Sound poll is now a major bellwether of critical opinion on cinema and this year’s edition (its eighth) is the largest ever, with 1,639 participating critics, programmers, curators, archivists and academics each submitting their top ten ballot. What has risen up the ranks? What has fallen? Has 2012’s winner Vertigo held on to its title? Find out below.

Fandom and AI generated music

If you haven’t discovered AI-generated songs by your favourite artists, then you’re missing a trick. Try I’m a Barbie Girl by Johnny Cash, for example, or Skyfall by Freddie Mercury. Amazing stuff.

This article is about the fandom around artists such as One Direction and Harry Styles, who are paying hard-earned real money for ‘leaks’ which may or may not be AI-generated music. No-one can tell the difference.

Discord communities within the Harry Styles and One Direction fandom are tearing themselves apart over “leaked snippets” of supposed demo songs that may or may not be AI-generated and are being sold to superfans for hundreds of dollars each.Source: The Specter of AI-Generated ‘Leaked Songs’ Is Tearing the Harry Styles Fandom Apart | 404 MediaThe controversy has turned into a days-long crowdsourced investigation and communitywide obsession, in which no one is really sure what’s real, what’s fake, whether they’re being scammed, or who or what made the songs that they’re listening to.

Over the last few weeks, a flurry of Harry Styles and One Direction snippets—which are short samples of a track designed to prove legitimacy so people will pay of the full thing—have begun popping up on YouTube, TikTok, and, most importantly, Discord, where they are being sold. The problem is no one can tell which, if any, of the songs are real, including AI-analysis companies who listened to the tracks for 404 Media.

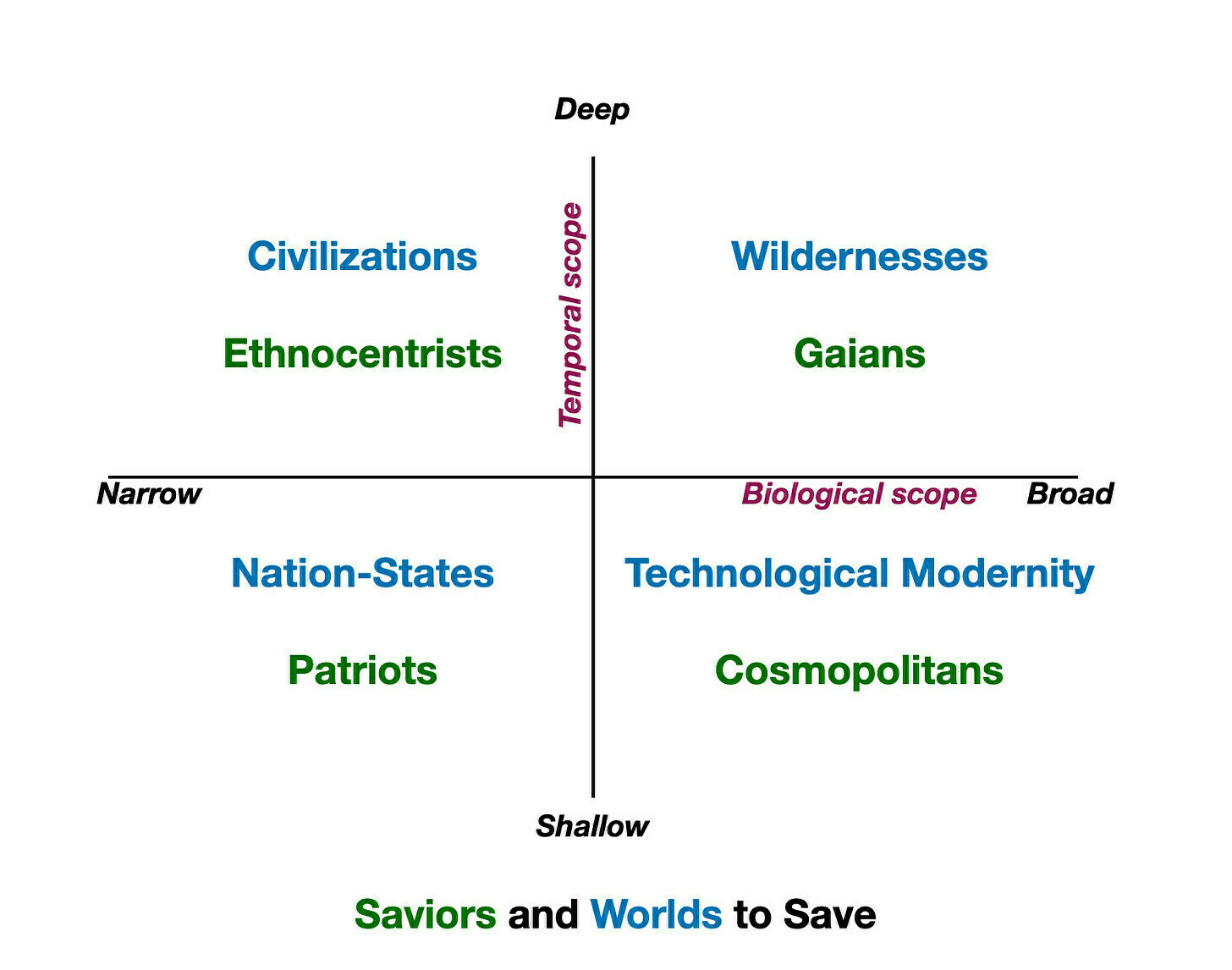

Saving the world using a 2x2 matrix

I’m a fan of Venkatesh Rao’s writing, and in this post he explores what we mean by ‘saving’ when we talk about ‘saving the world’. To do this, he uses a 2x2 matrix, categorising people’s motivations along two axes: biological scope and temporal scope. He identifies four types of “worlds” people aim to save: Civilisations, represented by ethnocentrists; Technological Modernity, represented by cosmopolitans; Modern Nations, represented by patriots; and the World as Wildernesses, represented by Gaians.

Rao himself identifies as a “cosmopolitan with Gaian tendencies,” advocating for a world that is rich in both contemporary technological potentialities and natural history. He argues that the focus should not be on saving the world but on “rewilding” it so that it becomes self-sustaining and doesn’t require saving.

Worlds constructed with biologically narrow scopes (which I’d define as somewhere between family/kinship groups to ethnicities and races, with perhaps a few animal species of cultural significance included, but always falling short of including all of humanity, let alone all of the biosphere) have all sorts of analytical problems that makes them intellectually fragile. But my main problem with them is that they are boringly impoverished to the point of deadness. Even if I could, with careful construction, make them “work” as worlds-to-save, and imagine sustainable futures where they are the entirety of the world, I don’t see the point.Source: What we seek to save when we seek to save the world | RibbonfarmBut apparently, a significant portion of humanity disagrees with me on this front. Many are attracted to the idea that their world-to-save can expand to become all that is; replacing a messy, illegible pluralism with a gloriously insipid and legible monoculture that reigns supreme with a firm, dead hand. I suspect the very intellectual fragility of these worlds is part of their appeal, much as fragility is part of the appeal of house-of-cards games.

[…]

For a cosmopolitan with Gaian tendencies, to save the modern world is to rewild and grow the global web of already slightly wild technological capabilities. Along with all the knowledge and resources — globally distributed in ways that cannot be cleanly factored across nations, civilizations, and other collective narcissisms — that is required to drive that web sustainably. And in the process, perhaps letting notions of civilization — including wishful notions of regulating and governing technology in “human centric” ways — fall by the wayside if they lack the vitality and imagination to accommodate technological modernity.

The complexities of distraction

I really enjoyed this essay by David Schurman Wallace in The Paris Review about being distracted while writing. It reminded me of a much shorter version of one my favourite books about writing: Out of Sheer Rage by Geoff Dyer.

Wallace delves into the complexities of distraction, using Gustave Flaubert’s unfinished novel Bouvard and Pécuchet as a lens to explore how our pursuits, whether intellectual or mundane, often become a chain of distractions. He argues that distraction isn’t necessarily a negative state but could be an essential part of the human condition, a byproduct of our ceaseless quest for knowledge and meaning.

I began writing this essay while putting off writing another one. My apartment is full of books I haven’t read, and others I read so long ago that I barely remember what’s in them. When I’m writing something, I’m often tempted to pick one up that has nothing to do with my subject. I’ve always wanted to read this, I think, idly flipping through, my eyes fixing on a stray phrase or two. Maybe it will give me a new idea.Source: In This Essay I Will: On Distraction | The Paris ReviewIn this moment of mild delusion, I’m distracted. I’ve always wanted to write an essay about distraction, I think. Add it to the laundry list of incomplete ideas I continue to nurse because some part of me suspects they will never come to fruition, and so will never have to be endured by readers. These are things you can keep in the drawer of your mind, glittering with unrealized potential. In the top row of my bedroom bookshelf is a copy of Flaubert’s final novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet. Something about it seems appropriate, though I’m not sure exactly what. I pluck it down.