- Build in 'Spaces' (for client projects, etc.)

- Split screen view

- Easel (clip *live* parts of web pages)

- Higher income & education demographics - Information-seeking traffic predominates, e.g., news, mail, search; Instagram, WhatsApp and Twitter are the dominant social media apps; games like Clash of Clans are the most widely used, …

- Lower income & education demographics - Entertainment traffic predominates, e.g., video-streaming, gaming, adult services; Facebook and Snapchat are the dominant social media apps; games like Candy Crush are the most widely used, …

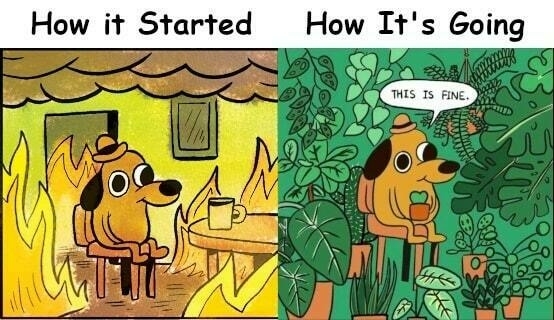

Remember distinct music scenes and culinary traditions? Yeah, they're coming back.

Anything that Anil Dash writes is worth reading and this, his first article for Rolling Stone, is no different. I haven’t quoted it here, but I love the first paragraph. What goes around, comes around, eh?

[T]his new year offers many echoes of a moment we haven’t seen in a quarter-century. Some of the most dominant companies on the internet are at risk of losing their relevance, and the rest of us are rethinking our daily habits in ways that will shift the digital landscape as we know it. Though the specifics are hard to predict, we can look to historical precedents to understand the changes that are about to come, and even to predict how regular internet users — not just the world’s tech tycoons — may be the ones who decide how it goes.Source: The Internet Is About to Get Weird Again | Rolling Stone[…]

We are about to see the biggest reshuffling of power on the internet in 25 years, in a way that most of the internet’s current users have never seen before. And while some of the drivers of this change have been hyped up, or even over-hyped, a few of the most important changes haven’t gotten any discussion at all.

[…]

Consider the dramatic power shift happening right now in social media. Twitter’s slide into irrelevance and extremism as it decays into X has hastened the explosive growth of a whole host of newer social networks. There’s the nerdy vibes of the noncommercial Mastodon communities (each one with its own set of Dungeons and Dragons rules to play by), the raucous hedonism of Bluesky (like your old Tumblr timeline at its most scandalous), and the at-least-it’s-not-LinkedIn noisiness of Threads, brought to you by Instagram, meaning Facebook, meaning Meta. There are lots more, of course, and probably another new one popping up tomorrow, but that’s what’s great about it. A generation ago, we saw early social networks like LiveJournal and Xanga and Black Planet and Friendster and many others come and go, each finding their own specific audience and focus. For those who remember a time in the last century when things were less homogenous, and different geographic regions might have their own distinct music scenes or culinary traditions, it’s easy to understand the appeal of an online equivalent to different, connected neighborhoods that each have their own vibe. While this new, more diffuse set of social networks sometimes requires a little more tinkering to get started, they epitomize the complexity and multiplicity of the weirder and more open web that’s flourishing today.

[...]I’m not a pollyanna about the fact that there are still going to be lots of horrible things on the internet, and that too many of the tycoons who rule the tech industry are trying to make the bad things worse. (After all, look what the last wild era online lead to.) There’s not going to be some new killer app that displaces Google or Facebook or Twitter with a love-powered alternative. But that’s because there shouldn’t be. There should be lots of different, human-scale alternative experiences on the internet that offer up home-cooked, locally-grown, ethically-sourced, code-to-table alternatives to the factory-farmed junk food of the internet. And they should be weird.

Image: DALL-E 3

Is this the end of the 'extremely online' era?

As I mentioned in a recent post, you can’t win a war against system designed to destroy your attention. You have to try a different strategy. One of those is disengaging, which is what Thomas J Bevan is noticing, and advocating for, in this post.

I like his mention of going to a place where he noticed there was “something off” and he realised nobody was using their phone. Not because they weren’t allowed to, but because they were having too much of a good time to bother with them.

<img class=“alignnone size-full wp-image-8855” src=“https://thoughtshrapnel.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DALL·E-2023-10-26-21.10.14-Vector-art-showing-a-massive-pile-of-smartphones-stacked-high-with-a-single-small-flower-growing-from-the-top-symbolising-hope-and-a-return-to-auth-1.png” alt=“Vector art showing a massive pile of smartphones stacked high, with a single, small flower growing from the top, symbolising hope and a return to authenticity.

" width=“1024” height=“1024” />

The consequences of life lived online have bled through into the real world and this has happened because we have allowed them to. It’s a cliché to say that real life is now a temporary reprieve from the online, as opposed to the other way around. We pay the price for all of this via boarded up shops, closing pubs, empty playgrounds and silent streets as each individual stays at home each night, enchanted by the blue flicker of their own little screen feeding them their own walled in world of news and content and edutainment.Source: The End of the Extremely Online Era | Thomas J BevanI believe it will end, this so-called way of life. Not through the Silicon Valley oligarchs spontaneously developing a conscience or being legislated into acting with a modicum less sociopathy. I don’t believe people will be frightened into changing how they act or suddenly shamed into putting their phones down for once in their lives. Such interventions don’t work with most addicts and more and more people are legitimately hooked on their devices than we are currently willing to countenance. No, I think this will all end, as T.S Eliot said, with a whimper. People will simply lose interest and walk away. Because the internet now is boring. People spend all day scrolling because they are trying to find what isn’t there anymore. The authenticity, the genuinely human moments, the fun.

Image: Created with DALL-E 3

In what ways does this technology increase people's agency?

This is a reasonably long article, part of a series by Robin Berjon about the future of the internet. I like the bit where he mentions that “people who claim not to practice any philosophical inspection of their actions are just sleepwalking someone else’s philosophy”. I think that’s spot on.

Ultimately, Berjon is arguing that the best we can hope for in a client/server model of Web architecture is a benevolent dictatorship. Instead, we should “push power to the edges” and “replace external authority with self-certifying systems”. It’s hard to disagree.

Whenever something is automated, you lose some control over it. Sometimes that loss of control improves your life because exerting control is work, and sometimes it worsens your life because it reduces your autonomy. Unfortunately, it's not easy to know which is which and, even more unfortunately, there is a strong ideological commitment, particularly in AI circles, to the belief that all automation, any automation is good since it frees you to do other things (though what other things are supposed to be left is never clearly specified).Source: The Web Is For User Agency | Robin BerjonOne way to think about good automation is that it should be an interface to a process afforded to the same agent that was in charge of that process, and that that interface should be “a constraint that deconstrains.” But that’s a pretty abstract way of looking at automation, tying it to evolvability, and frankly I’ve been sitting with it for weeks and still feel fuzzy about how to use it in practice to design something. Instead, when we’re designing new parts of the Web and need to articulate how to make them good even though they will be automating something, I think that we’re better served (for now) by a principle that is more rule-of-thumby and directional, but that can nevertheless be grounded in both solid philosophy and established practices that we can borrow from an existing pragmatic field.

That principle is user agency. I take it as my starting point that when we say that we want to build a better Web our guiding star is to improve user agency and that user agency is what the Web is for… Instead of looking for an impossible tech definition, I see the Web as an ethical (or, really, political) project. Stated more explicitly:

The Web is the set of digital networked technologies that work to increase user agency.

[…]

At a high level, the question to always ask is “in what ways does this technology increase people’s agency?” This can take place in different ways, for instance by increasing people’s health, supporting their ability for critical reflection, developing meaningful work and play, or improving their participation in choices that govern their environment. The goal is to help each person be the author of their life, which is to say to have authority over their choices.

A lonely and surveilled landscape

Kyle Chayka, writing in The New Yorker, points to what many of us have felt over the decade or so: the internet just isn’t fun any more. This makes me sad, as my kids will never experience what it was like.

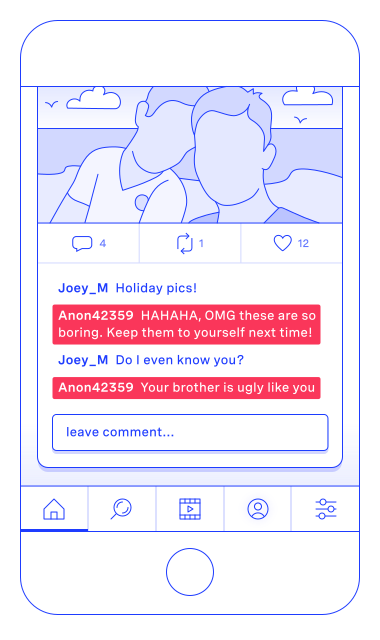

Instead of discovery and peer-to-peer relationships, we’ve got algorithms and influencer broadcasts. It’s an increasingly lonely and surveilled landscape. Thankfully, places of joy still exist, but they feel like pockets of resistance rather than mainstream hangouts.

The social-media Web as we knew it, a place where we consumed the posts of our fellow-humans and posted in return, appears to be over. The precipitous decline of X is the bellwether for a new era of the Internet that simply feels less fun than it used to be. Remember having fun online? It meant stumbling onto a Web site you’d never imagined existed, receiving a meme you hadn’t already seen regurgitated a dozen times, and maybe even playing a little video game in your browser. These experiences don’t seem as readily available now as they were a decade ago. In large part, this is because a handful of giant social networks have taken over the open space of the Internet, centralizing and homogenizing our experiences through their own opaque and shifting content-sorting systems. When those platforms decay, as Twitter has under Elon Musk, there is no other comparable platform in the ecosystem to replace them. A few alternative sites, including Bluesky and Discord, have sought to absorb disaffected Twitter users. But like sproutlings on the rain-forest floor, blocked by the canopy, online spaces that offer fresh experiences lack much room to grow.Source: Why the Internet Isn’t Fun Anymore | The New Yorker[…]

The Internet today feels emptier, like an echoing hallway, even as it is filled with more content than ever. It also feels less casually informative. Twitter in its heyday was a source of real-time information, the first place to catch wind of developments that only later were reported in the press. Blog posts and TV news channels aggregated tweets to demonstrate prevailing cultural trends or debates. Today, they do the same with TikTok posts—see the many local-news reports of dangerous and possibly fake “TikTok trends”—but the TikTok feed actively dampens news and political content, in part because its parent company is beholden to the Chinese government’s censorship policies. Instead, the app pushes us to scroll through another dozen videos of cooking demonstrations or funny animals. In the guise of fostering social community and user-generated creativity, it impedes direct interaction and discovery.

According to Eleanor Stern, a TikTok video essayist with nearly a hundred thousand followers, part of the problem is that social media is more hierarchical than it used to be. “There’s this divide that wasn’t there before, between audiences and creators,” Stern said. The platforms that have the most traction with young users today—YouTube, TikTok, and Twitch—function like broadcast stations, with one creator posting a video for her millions of followers; what the followers have to say to one another doesn’t matter the way it did on the old Facebook or Twitter. Social media “used to be more of a place for conversation and reciprocity,” Stern said. Now conversation isn’t strictly necessary, only watching and listening.

Adversarial interoperability to return to a world of 'fast companies'

Cory Doctorow is one of my favourite people on the entire planet. I’ve heard him speak in person and online on numerous occasions. I met him a couple of times while at Mozilla, and he’s even recommended swimming pools in Toronto to me when I visited. (He’s a daily swimmer due to chronic back pain.)

His new book, which I’m saving to read for my next holiday, is The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of Computation. In this interview as part of promoting the book, he talks about how we’ve ended up in a world without real competition in the technology marketplace. Essential reading, as ever.

There used to be a time when the tech sector could be described as a bunch of “fast companies,” right? They would use the interoperability that’s latent in all digital technology and they would specifically target whatever pain points the incumbent had introduced. If incumbents were making money by showing you ads, they made an ad blocker. If incumbents were making money by charging gigantic margins on hard drives, they made cheaper hard drives.Source: Cory Doctorow: Silicon Valley is now a world of ‘lumbering behemoths’ | Fast CompanyOver time, we went from an internet where tech companies more or less had their users’ backs, to an internet where tech companies are colluding to take as big a bite as possible out of those users. We do not have fast companies anymore; we have lumbering behemoths. If you’ve started a fast company, it’s probably just a fake startup that you’re hoping to get acqui-hired by one of the big giants, which is something that used to be illegal.

As these companies grew more concentrated, they were able to collude and convince courts and regulators and lawmakers that it was time to get rid of the kind of interoperability, the reverse engineering that had been a feature of technology since the very beginning, and move into a new era in which no one was allowed to do anything to a tech platform that their shareholders wouldn’t appreciate. And that the government should step in to use the state’s courts to punish anyone who disagrees. That’s how we got to the world that we’re in today.

Switching to Arc

It’s not often I’ll post tools here, but after a few days of using it, I’m sold on the Arc browser.

My web browser history over the last quarter of a century goes something like: Netscape Navigator –> Internet Explorer –> Firefox –> Chrome –> Brave –> Arc.

Perhaps I should record a screencast, but the three things I like most about Arc are:

Experience a calmer, more personal internet in this browser designed for you. Let go of the clicks, the clutter, the distractions.Source: Arc | The Browser Company

Cambrian governance models

I think it’s fair to say that this article features ‘florid prose’ but the gist is that we should want society to be as complex as possible. This allow innovation to flourish and means we can solve some of the knottiest problems facing our world.

However, we’re hamstrung by issues around transnational governance, and particularly in the digital realm.

To summarise, we are traversing an epochal change and we lack the institutional capacity to complete this transformation without imploding. We could well fail, and the consequences of failure at this juncture would be catastrophic. However, we can collectively rise to the challenge and an exciting assemblage of subfields is emerging to help. We can fix the failed state that is the Internet if we approach building tech with institutional principles, and an Internet that delivers on its cooperative promise of deeper, denser institutional capacity is what we need as a planetary civilisation.Source: The Internet Transition | Robin BerjonWe don’t need a worldwide technical U.N. to figure this out. Rather, we need transnational topic-specific governance systems that interact with one another wherever they connect and overlap but that do not control one another, and that exercise subsidiarity to one another as well as to more local institutions. Yes, it will be a glorious mess — a Cambrian mess — but we will be collectively smarter for it.

Spring '83

John Johnston put me onto this via a comment on my personal blog. Spring ‘83 is a protocol developed by Robin Sloan, multi-talented developer, olive farm owner, and author of novels such as Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore.

The internet these days is much less fun and weird than it used to be, which is sad. Here’s an example of the protocol in action at the site spring83.mozz.us and you can have a play about at The Oakland Follower Sentinel by creating your own keypair (see the blue sidebar!)

For me, the recent resurgence of the email newsletter feels not much like a renaissance, and more like a massing of exhausted refugees in the last reliable shelter. I’m glad we have it; but email cannot be the end of the story, either.Source: Specifying Spring ‘83 | Robin SloanI’m dissembling a bit. The truth is, I reject Twitter, RSS, and email also because … I am hyped up to invent things!

So it came to pass that I found myself dreaming about designs that might satisfy my requirements, while also supporting new interactions, new ways of relating, new aesthetics. At the same time, I read a ton about the early days of the internet. I devoured oral histories; I dug into old protocols.

The crucial spark was RFC 865, published by the great Jon Postel in May 1983. The modern TCP/IP internet had only just come online that January, can you believe it? RFC 865 describes a Quote of the Day Protocol:

A server listens for TCP connections on TCP port 17. Once a connection is established a short message is sent out the connection (and any data received is thrown away). The service closes the connection after sending the quote.That’s it. That’s the protocol.I read RFC 865, and I thought about May 1983. How the internet might have felt at that moment. Jon Postel maintained its simple DNS by hand. There was a time when, you wanted a computer to have a name on the internet, you emailed Jon.

There’s a way of thinking about, and with, the internet of that era that isn’t mere nostalgia, but rather a conjuring of the deep opportunities and excitements of this global machine. I’ll say it again. There are so many ways people might relate to one another online, so many ways exchange and conviviality might be organized.

Spring ‘83 isn’t over yet.

The internet is broken because the internet is a business

I ended up cancelling my Verso books subscription because I was overwhelmed with the number of amazing books coming out every month. This looks like one to keep an eye out for.

Several decades into our experiment with the internet, we appear to have reached a crossroads. The connection that it enables and the various forms of interaction that grow out of it have undoubtedly brought benefits. People can more easily communicate with the people they love, access knowledge to keep themselves informed or entertained, and find myriad new opportunities that otherwise might have been out of reach.Source: The Privatized Internet Has Failed Us | JacobinBut if you ask people today, for all those positive attributes, they’re also likely to tell you that the internet has several big problems. The new Brandeisian movement calling to “break up Big Tech” will say that the problem is monopolization and the power that major tech companies have accrued as a result. Other activists may frame the problem as the ability of companies or the state to use the new tools offered by this digital infrastructure to intrude on our privacy or restrict our ability to freely express ourselves. Depending on how the problem is defined, a series of reforms are presented that claim to rein in those undesirable actions and get companies to embrace a more ethical digital capitalism.

There’s certainly some truth to the claims of these activists, and aspects of their proposed reforms could make an important difference to our online experiences. But in his new book ‘Internet for the People: The Fight for Our Digital Future’, Ben Tarnoff argues that those criticisms fail to identify the true problem with the internet. Monopolization, surveillance, and any number of other issues are the product of a much deeper flaw in the system.

“The root is simple,” writes Tarnoff: “The internet is broken because the internet is a business.”

Muting the American internet

This is a humorous article, but one with a point.

[W]e need a way to mute America. Why? Because America has no chill. America is exhausting. America is incapable of letting something be simply funny instead of a dread portent of their apocalyptic present. America is ruining the internet.Source: I Should Be Able to Mute America | Gawker[…]

The greatest trick America’s ever pulled on the subjects of its various vassal states is making us feel like a participant in its grand experiment. After all, our fate is bound to the American empire’s whale fall. My generation in particular is the first pure batch of Yankee-Yobbo mutoids: as much Hank Hill as we are Hills Hoist (look it up!), as familiar with the Supreme Court Justices as we are with the judges on Master Chef, as comfortable in Frasier’s Seattle or Seinfeld’s Upper West Side as we are in Ramsay Street or Summer Bay.

[…]

I should not know who Pete Buttigieg is. In a just world, the name Bari Weiss would mean as much to me as Nordic runes. This goes for people who actually might read Nordic runes too. No Swede deserves to be burdened with this knowledge. No Brazilian should have to regularly encounter the phrase “Dimes Square.” To the rest of the vast and varied world, My Pillow Guy and Papa John should be NPCs from a Nintendo DS Zelda title, not men of flesh and bone, pillow and pizza. Ted Cruz should be the name of an Italian pornstar in a Love Boat porn parody. Instead, I’m cursed to know that he is a senator from Texas who once stood next to a butter sculpture of a dairy cow and declared that his daughter’s first words were “I like butter.”

Muting the American internet

This is a humorous article, but one with a point.

[W]e need a way to mute America. Why? Because America has no chill. America is exhausting. America is incapable of letting something be simply funny instead of a dread portent of their apocalyptic present. America is ruining the internet.Source: I Should Be Able to Mute America | Gawker[…]

The greatest trick America’s ever pulled on the subjects of its various vassal states is making us feel like a participant in its grand experiment. After all, our fate is bound to the American empire’s whale fall. My generation in particular is the first pure batch of Yankee-Yobbo mutoids: as much Hank Hill as we are Hills Hoist (look it up!), as familiar with the Supreme Court Justices as we are with the judges on Master Chef, as comfortable in Frasier’s Seattle or Seinfeld’s Upper West Side as we are in Ramsay Street or Summer Bay.

[…]

I should not know who Pete Buttigieg is. In a just world, the name Bari Weiss would mean as much to me as Nordic runes. This goes for people who actually might read Nordic runes too. No Swede deserves to be burdened with this knowledge. No Brazilian should have to regularly encounter the phrase “Dimes Square.” To the rest of the vast and varied world, My Pillow Guy and Papa John should be NPCs from a Nintendo DS Zelda title, not men of flesh and bone, pillow and pizza. Ted Cruz should be the name of an Italian pornstar in a Love Boat porn parody. Instead, I’m cursed to know that he is a senator from Texas who once stood next to a butter sculpture of a dairy cow and declared that his daughter’s first words were “I like butter.”

The new digital divide

We’re already at the stage where most people in the developed world have a device that can access the internet in their pocket. Many families have multiple devices in their house that can access the internet. We’re getting to the stage where that’s starting to be the case in developing countries.

So the new digital divide? How we use the internet. I think there’s a lot to unpack here, especially as we live in unequal societies dominated by hyper-capitalism. It would be easy to victim blame, but I know from experience that when I’m burned out, all I want to do is stare and scroll at my phone…

In his seminar, Moro referred to the socio-economic divide based on how we use the internet as the second digital divide, in contrast to the original digital divide which was based on access to the internet.Source: The Digital Divide in How We Use the Internet | Irving Wladawsky-BergerGetting online in the 1990s required a personal computer and an account with a service provider, and e-commerce transactions required a credit card and bank account. As our economy was becoming increasingly digital, major new inequalities were now arising because so many around the world could neither afford a PC or an internet account and had no bank relationship or credit card. The reach and connectivity we were all so excited about in this initial phase of the internet era was in reality not so inclusive. While the internet was truly empowering for those with the means to use it, it led to a growing digital divide both within countries and across the world. The internet was ushering a global digital revolution, but it was disconcerting to have a global digital revolution that left out the majority of the world’s population.

This picture started to change in the 2000s. Continuing technology advances were now bringing the empowerment benefits of the digital revolution to a majority of the planet’s population. Mobile phones and wireless internet access went from a luxury to a necessity that most everyone could now afford, initially in advanced economies, and later in most of the rest of the world. We were transitioning from the connected economy of PCs, browsers and web servers to an increasingly hyperconnected digital economy of ubiquitous, powerful and inexpensive mobile devices, cloud-based apps, and broadband wireless networks.

While the original internet access gap is now minimal in developed economies, Moro and his collaborators found that a digital usage gap has now emerged, representing the distinct uses of the internet by different socio-economic groups based primarily on their income and educational status.

[…]

The study found quantitative evidence of a significant digital divide in internet usage between two socio-economic groups, each with different income and educational attainment. In principle, all individuals had access to the same internet. But, the study found that each group generally accessed its own distinct version of the internet, and their socio-economic behavior was thus influenced by the fairly different services and information that they were exposed to. By analyzing mobile traffic flows, the study identified the key services that each group accessed:

“The digital usage gap is so profound between low- and high-income or low- or high-education areas that it can be used to clearly distinguish between them or even identify the relative composition of these groups in a given area,” wrote the authors. “High-income areas or those with higher education attainability show a more pronounced utilization of mobile devices to consume news, exchange e-mails, search for information or listen to music. At the same time, they display a reduced use of some social media platforms or video-streaming services.

Image source: Robin Worrall

Signalling that you're AFK in a world where you can never really be AFK

I used AIM and MSN Messenger as a teenager, from around 1996 to about 2001. It was great, and I remember messaging with friends and the woman who is now my wife using it.

Part of the whole experience of it was that you were using the service on a shared device, a computer that the rest of the family would use. In that sense, it was more like a text-based landline phone. It wasn’t personal like the smart devices that live in our pockets these days.

There a lot of nostalgia about how things used to be, and we’re certainly not going back to shared devices as a primary means of getting online anytime soon. So that means that we need other ways of respecting one another’s boundaries. This is something we can actually reclaim ourselves by responding to messages on our own terms.

Sometimes you had to step away. So you threw up an Away Message: I’m not here. I’m in class/at the game/my dad needs to use the comp. I’ve left you with an emo quote that demonstrates how deep I am. Or, here’s a song lyric that signals I am so over you. Never mind that my Away Message is aimed at you.Source: It's Time to Bring Back the AIM Away Message | WIREDI miss Away Messages. This nostalgia is layered in abstraction; I probably miss the newness of the internet of the 1990s, and I also miss just being … away. But this is about Away Messages themselves—the bits of code that constructed Maginot Lines around our availability. An Away Message was a text box full of possibilities, a mini-MySpace profile or a Facebook status update years before either existed. It was also a boundary: An Away Message not only popped up as a response after someone IM’d you, it was wholly visible to that person b they IM’d you.

Nothing like this exists in our modern messaging apps.

[…]

People send too many messages. I send too many messages. The first step in making messaging amends is to admit that you, too, are an inconsiderate messaging maniac.

But I’ll never stop, and neither will you. Quick messaging is a utility. It is, in many cases, the most efficient and meaningful form of communication we have. It’s crucial for relationship building, for organizing, for supporting others through hard times. It can be joyful.

[…]

Would something like the Away Message, a relic from an era when we just didn’t message so darn much, actually put up the guardrails we need? Maybe not. But I’m willing to try anything at this point. If we can’t ever get away from messages, at the very least we can create a digital simulacrum of ourselves that appears to be away. What else is the internet for?