- Do Experts Listen to Other Experts? (Marginal Revolution) —"very little is known about how experts influence each others’ opinions, and how that influence affects final evaluations."

- Why Symbols Aren’t Forever (Sapiens) — "The shifting status of cultural symbols reveals a lot about who we are and what we value."

- Balanced Anarchy or Open Society? (Kottke.org) — "Personal computing and the internet changed (and continues to change) the balance of power in the world so much and with such speed that we still can’t comprehend it."

What people are really using generative AI for

As I’ve written several times before here on Thought Shrapnel, society seems to act as though the giant, monolithic, hugely profitable porn industry just doesn’t… exist? This despite the fact it tends to be a driver of technical innovation. I won’t get into details, but feel free to search for phrases such as ‘teledildonics’.

So this article from the new (and absolutely excellent) 404 Media on a venture capitalist firm’s overview of the emerging generative AI industry shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. As a society and as an industry, we don’t make progress on policy, ethics, and safety by pretending things aren’t happening.

As the father, seeing this kind of news is more than a little disturbing. And we don’t deal with all of it by burying our head in the sand, shaking our head, or crossing our fingers.

The Andreesen Horowitz (also called a16z) analysis is derived from crude but telling data—internet traffic. Using website traffic tracking company Similarweb, a16z ranks the top 50 generative AI websites on the internet by monthly visits, as of June 2023. This data provides an incomplete picture of what people are doing with AI because it’s not tracking use of popular AI apps like Replika (where people sext with virtual companions) or Telegram chatbots like Forever Companion, which allows users to talk to chatbots trained on the voices of influencers like Amouranth and Caryn Marjorie (who just want to talk about sex).Source: 404 Media Generative AI Market Analysis: People Love to Cum[…]

What I can tell you without a doubt by looking at this list of the top 50 generative AI websites is that, as has always been the case online and with technology generally, porn is a major driving force in how people use generative AI in their day to day lives.

[…]

Even if we put ethical questions aside, it is absurd that a tech industry kingmaker like a16z can look at this data, write a blog titled “How Are Consumers Using Generative AI?” and not come to the obvious conclusion that people are using it to jerk off. If you are actually interested in the generative AI boom and you are not identifying porn as core use for the technology, you are either not paying attention or intentionally pretending it’s not happening.

AI and bullshit jobs

I had the pleasure of working with the large-brained Helen Beetham when I was at Jisc just over a decade ago. In this long-ish post, she covers quite a few areas of, with plenty of links, and pulls the threads together around graduate jobs and an AI curriculum.

While I could have quoted a lot of this, especially around innovation, the stories being told to graduates, and the neo-colonial nature of AI companies, I’ve gone for the last three paragraphs in which Helen discusses bullshit jobs. I’d highly recommend reading the whole thing.

My hope is that, rather than a curriculum ‘for AI’, these conversations would create space for learning that addresses human challenges. Getting life on earth out of the mess that fossil fuels and rampant production have made of it will take all the graduate labour we can produce and more. Nobody is going to be without meaningful work - not climate scientists or green energy specialists or engineers or geologists or computer scientists or materials chemists or statisticians. Not a single person educated in the STEM subjects beloved of governments everywhere can be left idle. But nor are we getting out of this without social scientists to help us weather the social and economic and political storms, humanities graduates to develop new laws and policies, new philosophies and imagined futures, and professionals committed to a just transition in their own spheres of work. And there are other crises, entwined with the climate crisis, that graduates need and want to address, such as galloping economic inequality, crises of democracy and human rights, food and water shortages, and the crisis of care. Universities can offer fewer and fewer guarantees of secure employment and decent pay, but they can offer meaningful work, justifying students’ investment in the future.Source: ‘Luckily, we love tedious work’ | Helen BeethamThe longer you look at the things ChatGPT can do, the more they resemble what David Graeber described as Bullshit Jobs - jobs that don’t need doing. While I don’t agree with the way he singles out specific job roles, Graeber is surely right that more and more work involves doing things with data and information and ‘content’ that has no value beyond maintaining those systems. And one claim he made that is borne out by workplace research is that meaningless work is bad for people’s mental health.

It’s a nice little aphorism that ‘if AI can do your job, AI should do your job’. But here’s a different one. If AI can ‘do’ your job, you deserve a better job. And if meaningless jobs are bad for workers’ mental health, how much worse are they for all our futures? The phrase ‘fiddling while Rome burns’ hardly begins to cover our present situation. As the polycrisis heats up, the crisis of not enough water-cooler text is not something any graduate should have to care about, nor any university curriculum either.

Everyone has something to teach

As someone who is apparently in a microgeneration between Generation X and Millennials, I feel constantly the tension between the “old ways” of doing things and the “throwing things against the wall to see what sticks” approach.

This article frames the issue nicely: everyone has something to teach, no matter whether you’re the person with lots of experience to share, or the person with the new approach.

Gaining experience takes time, effort, and often comes at the price of making painful mistakes. You don’t want to let those lessons go. You want them to mean something, to help you from making the same painful mistakes again. To help others from making the same mistakes you made. So it will always be the case that those with the most experience – and the good, smart, accurate wisdom that comes from it – will be the least willing to adapt their views as the world evolves.Source: Experts From A World That No Longer Exists · Collaborative FundNeither should be the case, because every generation cycles through the same process. Today’s older generation once understood the world better than their parents, who scoffed at them. Today’s younger generation will one day be stuck in the antiquated norms of their past, and their kids will scoff at them. I can imagine my son in 80 years screaming, “Get off my metaverse lawn!”

One takeaway from this is that no age has a monopoly on insight, and different levels of experience offer different kinds of lessons. Vishal Khandelwal recently wrote that old guys don’t understand tech, but young guys don’t understand risk. Another way to put it is: everyone has something to teach.

Image: CC BY Tea, two sugars

Friday forebodings

I think it's alright to say that this was a week when my spirits dropped a little. Apologies if that's not what you wanted to hear right now, and if it's reflected in what follows.

For there to be good things there must also be bad. For there to be joy there must also be sorrow. And for there to be hope there must be despair. All of this will pass.

We’re Finding Out How Small Our Lives Really Are

But there’s no reason to put too sunny a spin on what’s happening. Research has shown that anticipation can be a linchpin of well-being and that looking ahead produces more intense emotions than retrospection. In a 2012 New York Times article on why people thirst for new experiences, one psychologist told the paper, “Novelty-seeking is one of the traits that keeps you healthy and happy and fosters personality growth as you age,” and another referred to human beings as a “neophilic species.” Of course, the current blankness in the place of what comes next is supposed to be temporary. Even so, lacking an ability to confidently say “see you later” is going to have its effects. Have you noticed the way in which conversations in this era can quickly become recursive? You talk about the virus. Or you talk about what you did together long ago. The interactions don’t always spark and generate as easily as they once did.

Spencer Kornhaber (The Atlantic)

Part of the problem with all of this is that we don't know how long it's going to last, so we can't really make plans. It's like an extended limbo where you're supposed to just get on with it, whatever 'it' is...

Career Moats in a Recession

If you're going after a career moat now, remember that the best skills to go after are the ones that the market will value after the recession ends. You can’t necessarily predict this — the world is complex and the future is uncertain, but you should certainly keep the general idea in mind.

A simpler version of this is to go after complementary skills to your current role. If you've been working for a bit, it's likely that you'll have a better understanding of your industry than most. So ask yourself: what complementary skills would make you more valuable to the employers in your job market?

Cedric James (Commonplace)

I'm fortunate to have switched from education to edtech at the right time. Elsewhere, James says that "job security is the ability to get your next job, not keep your current one" and that this depends on your network, luck, and having "rare and valuable skills". Indeed.

Everything Is Innovative When You Ignore the Past

This is hard stuff, and acknowledging it comes with a corollary: We, as a society, are not particularly special. Vinsel, the historian at Virginia Tech, cautioned against “digital exceptionalism,” or the idea that everything is different now that the silicon chip has been harnessed for the controlled movement of electrons.

It’s a difficult thing for people to accept, especially those who have spent their lives building those chips or the software they run. “Just on a psychological level,” Vinsel said, “people want to live in an exciting moment. Students want to believe they’re part of a generation that’s going to change the world through digital technology or whatever.”

Aaron Gordon (VICE)

Everyone thinks they live in 'unprecedented' times, especially if they work in tech.

‘We can’t go back to normal’: how will coronavirus change the world?

But disasters and emergencies do not just throw light on the world as it is. They also rip open the fabric of normality. Through the hole that opens up, we glimpse possibilities of other worlds. Some thinkers who study disasters focus more on all that might go wrong. Others are more optimistic, framing crises not just in terms of what is lost but also what might be gained. Every disaster is different, of course, and it’s never just one or the other: loss and gain always coexist. Only in hindsight will the contours of the new world we’re entering become clear.

Peter C Baker (the Guardian)

An interesting read, outlining the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios. The coronavirus pandemic is a crisis, but of course what comes next (CLIMATE CHANGE) is even bigger.

The Terrible Impulse To Rally Around Bad Leaders In A Crisis

This tendency to rally around even incompetent leaders makes one despair for humanity. The correct response in all cases is contempt and an attempt, if possible, at removal of the corrupt and venal people in charge. Certainly no one should be approving of the terrible jobs they [Cuomo, Trump, Johnson] have done.

All three have or will use their increased power to do horrible things. The Coronavirus bailout bill passed by Congress and approved by Trump is a huge bailout of the rich, with crumbs for the poor and middle class. So little, in fact, that there may be widespread hunger soon. Cuomo is pushing forward with his cuts, and I’m sure Johnson will live down to expectations.

Ian Welsh

I'm genuinely shocked that the current UK government's approval ratings are so high. Yes, they're covering 80% of the salary of those laid-off, but the TUC was pushing for an even higher figure. It's like we're congratulating neoliberal idiots for destroying our collectively ability to be able to respond to this crisis effectively.

As Coronavirus Surveillance Escalates, Personal Privacy Plummets

Yet ratcheting up surveillance to combat the pandemic now could permanently open the doors to more invasive forms of snooping later. It is a lesson Americans learned after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, civil liberties experts say.

Nearly two decades later, law enforcement agencies have access to higher-powered surveillance systems, like fine-grained location tracking and facial recognition — technologies that may be repurposed to further political agendas like anti-immigration policies. Civil liberties experts warn that the public has little recourse to challenge these digital exercises of state power.

Natasha Singer and Choe Sang-Hun (The New York Times)

I've seen a lot of suggestions around smarpthone tracking to help with the pandemic response. How, exactly, when it's trivial to spoof your location? It's just more surveillance by the back door.

How to Resolve Any Conflict in Your Team

Have you ever noticed that when you argue with someone smart, if you manage to debunk their initial reasoning, they just shift to a new, logical-sounding reason?

Reasons are like a salamander’s legs — if you cut one off, another grows in its place.

When you’re dealing with a salamander, you need to get to the heart. Forget about reasoning and focus on what’s causing the emotions. According to [non-violent communication], every negative emotion is the result of an unmet, universal need.

Dave bailey

Great advice here, especially for those who work in organisations (or who have clients) who lack emotional intelligence.

2026 – the year of the face to face pivot

When the current crisis is over in terms of infection, the social and economic impact will be felt for a long time. One such hangover is likely to be the shift to online for so much of work and interaction. As the cartoon goes “these meetings could’ve been emails all along”. So let’s jump forward then a few years when online is the norm.

Martin Weller (The Ed Techie)

Some of the examples given in this post gave me a much-needed chuckle.

Now's the time – 15 epic video games for the socially isolated

However, now that many of us are finding we have time on our hands, it could be the opportunity we need to attempt some of the more chronologically demanding narrative video game masterpieces of the last decade.

Keith Stuart (The Guardian)

Well, yes, but what we probably need even more is multiplayer mode. Red Dead Redemption II is on this list, and it's one of the best games ever made. However, it's tinged with huge sadness for me as it's a game I greatly enjoyed playing with the late, great, Dai Barnes.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup, become a supporter, or download Thought Shrapnel Vol.1: Personal Productivity!

Header image by Alex Fu

We don’t receive wisdom; we must discover it for ourselves after a journey that no one can take us on or spare us

So said Marcel Proust, that famous connoisseur of les petites madeleines. While I don't share his effete view of the world, I do like French cakes and definitely agree with his sentiments on wisdom.

Earlier this week, Eylan Ezekiel shared this Nesta Landscape of innovation approaches with our Slack channel. It's what I would call 'slidebait' — carefully crafted to fit onto slide decks in keynotes around the world. It's a smart move because it gets people talking about your organisation.

In my opinion, how these things are made is more interesting than the end result. There are inevitably value judgements when creating anything like this, and, because Nesta have set it out as overlapping 'spaces', the most obvious takeaway from the above diagram is that those innovation approaches sitting within three overlapping spaces are the 'most valuable' or 'most impactful'. Is that true?

A previous post on this topic from the Nesta blog explains:

Although this map is neither exhaustive nor definitive – and at some points it may seem perhaps a little arbitrary, personal choice and preference – we have tried to provide an overview of both commonly used and emerging innovation approaches.

Bas Leurs (formerly of nesta)

When you're working for a well-respected organisation, you have to be really careful, because people can take what you produce as some sort of Gospel Truth. No matter how many caveats you add, people confuse the map with the territory.

I have some experience with creating a 'map' for a given area, as I was Mozilla's Web Literacy Lead from 2013 to 2015. During that time, I worked with the community to take the Web Literacy Standard Map from v0.1 to v1.5.

Digital literacies of various types are something I've been paying attention to for around 15 years now. And, let me tell, you, I've seen some pretty bad 'maps' and 'frameworks'.

For example, here's a slide deck for a presentation I did for a European Commission Summer School last year, in which I attempted to take the audience on a journey to decide whether a particular example I showed them was any good:

If you have a look at Slide 14 onwards, you'll see that the point I was trying to make is that you have no way of knowing whether or not a shiny, good-looking map is any good. The organisation who produced it didn't 'show their work', so you have zero insight into its creation and the decisions taken in its creation. Did their intern knock it up on a short deadline? We'll never know.

The problem with many think tanks and 'innovation' organisations is that they move on too quickly to the next thing. Instead of sitting with something and let it mature and flourish, as soon as the next bit of funding comes in, they're off like a dog chasing a shiny car. I'm not sure that's how innovation works.

Before Mozilla, I worked at Jisc, which at the time funded innovation programmes on behalf of the UK government and disseminated the outcomes. I remember a very simple overview from Jisc's Sustaining and Embedding Innovations project that focused on three stages of innovation:

Invention

This is about the generation of new ideas e.g. new ways of teaching and learning or new ICT solutions.Early Innovation

This is all about the early practical application of new inventions, often focused in specific areas e.g. a subject discipline or speciality such as distance learning or work-based learning.Systemic Innovation

Jisc

This is where an institution, for example, will aim to embed an innovation institutionally.

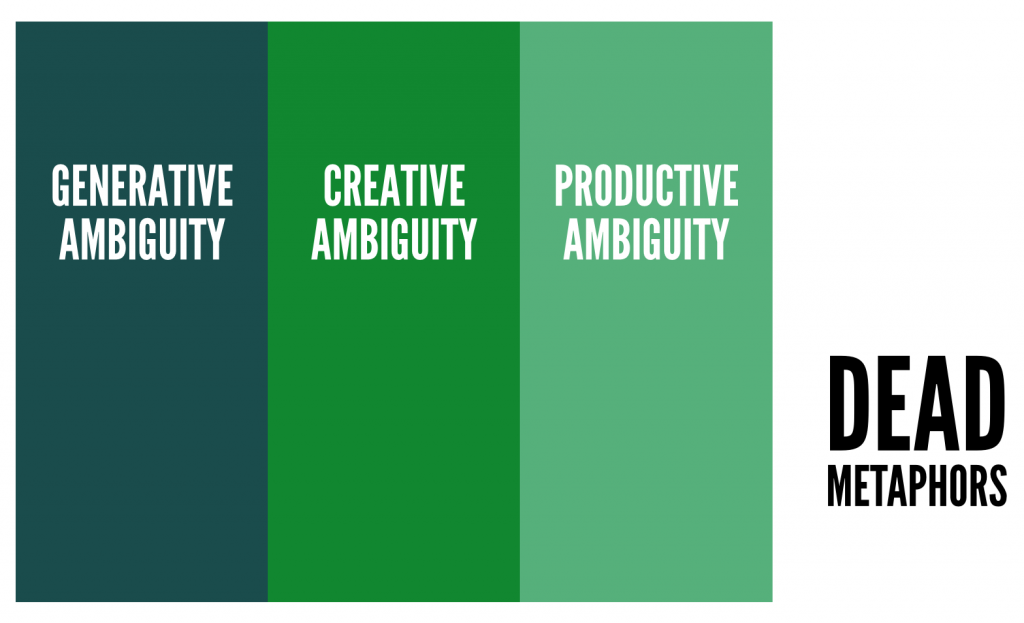

The problem with many maps and frameworks, especially around digital skills and innovation, is that they remove any room for ambiguity. So, in an attempt not to come across as vague, they instead become 'dead metaphors'.

I don't think I've ever seen an example where, without any contextualisation, an individual or organisation has taken something 'off the shelf' and applied it to achieve uniformly fantastic results. That's not how these things work.

Humans are complex organisms; we're not machines. For a given input you can't expect the same output. We're not lossless replicators.

So although it takes time, effort, and resources, you've got to put in the hard yards to see an innovation through all three of those stages outlined by Jisc. Although the temptation is to nail things down initially, the opposite is actually the best way forward. Take people on a journey and get them to invest in what's at stake. Embrace the ambiguity.

I've written more about this in a post I wrote about a 5-step process for creating a sustainable digital literacies curriculum. It's something I'll be thinking about more as I reboot my consultancy work (through our co-op) for 2020!

For now, though, remember this wonderful African proverb:

The smallest deed is better than the greatest intention

Thanks to John Burroughs for today's title. For me, it's an oblique reference to some of the situations I find myself in, both in my professional and personal life. After all, words are cheap and actions are difficult.

I'm going to take the unusual step of quoting someone who's quoting me. In this case, it's Stephen Downes picking up on a comment I made in the cc-openedu Google Group. I'd link directly to my comments, but for some reason a group about open education is... closed?

I'd like to echo a point David Kernohan made when I worked with him on the Jisc OER programme. He said: "OER is a supply-side term". Let's face it, there are very few educators specifically going out and looking for "Openly Licensed Resources". What they actuallywant are resources that they can access for free (or at a low cost) and that they can legally use. We've invented OER as a term to describe that, but it may actually be unhelpfully ambiguous.

Shortly after posting that, I read this post from Sarah Lambert on the GO-GN (Global OER Graduate Network) blog. She says:

[W]hile we’re being all inclusive and expanding our “open” to encompass any collaborative digital practice, then our “open” seems to be getting less and less distinctive. To the point where it’s getting quite easily absorbed by the mainstream higher education digital learning (eLearning, Technology Enhanced Learning, ODL, call it what you will). Is it a win for higher education to absorb and assimilate “open” (and our gift labour) as the latest innovation feeding the hungry marketised university that Kate Bowles spoke so eloquently about? Is it a problem if not only the practice, but the research field of open education becomes inseparable with mainstream higher education digital learning research?

My gloss on this is that 'open education' may finally have moved into the area of productive ambiguity. I talked about this back in 2016 in a post on a blog I post to only very infrequently, so I might as well quote myself again:

Ideally, I’d like to see ‘open education’ move into the realm of what I term productive ambiguity. That is to say, we can do some workwith the idea and start growing the movement beyond small pockets here and there. I’m greatly inspired by Douglas Rushkoff’s new Team Human podcast at the moment, feeling that it’s justified the stance that I and others have taken for using technology to make us more human (e.g. setting up a co-operative) and against the reverse (e.g. blockchain).

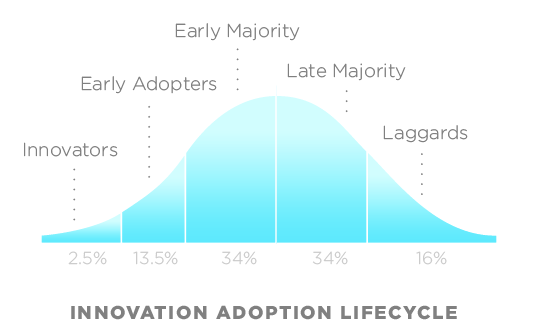

That's going to make a lot of people uncomfortable, and hopefully uncomfortable enough to start exploring new, even better areas. 'Open Education' now belongs, for better or for worse, to the majority. Whether that's 'Early majority' or 'Late majority' on the innovation adoption lifecycle curve probably depends where in the world you live.

Things change and things move on. The reason I used that xkcd cartoon about IRC at the top of this post is because there has been much (OK, some) talk about Mozilla ending its use of IRC.

While we still use it heavily, IRC is an ongoing source of abuse and harassment for many of our colleagues and getting connected to this now-obscure forum is an unnecessary technical barrier for anyone finding their way to Mozilla via the web. Available interfaces really haven’t kept up with modern expectations, spambots and harassment are endemic to the platform, and in light of that it’s no coincidence that people trying to get in touch with us from inside schools, colleges or corporate networks are finding that often as not IRC traffic isn’t allowed past institutional firewalls at all.

Cue much hand-wringing from the die-hards in the Mozilla community. Unfortunately, Slack, which originally had a bridge/gateway for IRC has pulled up the drawbridge on that front, so they could go with something like Mattermost, but given recently history I bet they go with Discord (or similar).

As Seth Godin points out in his most recent podcast episode, everyone wants be described as 'supple', nobody wants to be described as 'brittle'. Yet, the actions we take suggest otherwise. We expect that just because the change we see in the world isn't convenient, that we can somehow slow it down. Nope, you just have to roll with it, whether that's changing technologies, or different approaches to organising ideas and people.

Also check out:

On 'academic innovation'

Rolin Moe is in a good position to talk on the topic of ‘academic innovation’. In fact, it’s literally in his job title: ‘Assistant professor and Director of the Institute for Academic Innovation at Seattle Pacific University".

Moe warns, however, that it’s not necessarily a great idea to create a new discipline out of academic innovation. Until fairly recently, being ‘innovative’ was a negative slur, something that could get you in some serious trouble if you were found guilty.

[T]he historical usage of innovation is not as a foundational platform but a superficial label; yet in 2018 the governing bodies of societal institutions wield “innovation” in setting forth policy, administration and funding. Innovation, a term we all know but do not have a conceptual framework for, is driving change and growth in education. As regularly used without context, innovation is positioned as the future out-of-the-box solution for the problems of the present.Words and terms, of course, change over time. But, as Moe points out, if we’re to update the definition of innovation, we need a common understanding of what it means.This makes the term a conduit of power relationships despite many proponents of innovation serving as vocal advocates for diversity, equity and inclusion in higher education. Thinking about revenue shortfalls in a time of national economic prosperity, the extraction of arts and humanities programs at a time when industry demands critical thinking from graduates, and the positioning of online learning as a democratizing tool when research shows the greatest benefit is to populations of existing privilege, the solutions offered under the innovation mantle have at best affected symptoms, at worst perpetuated causes.

Coalescing around a common understanding is vital for the growth of “academic innovation,” but the history of innovation makes this concept problematic. Some have argued that innovation binds together disciplines such as learning technologies, leadership and change, and industrial/organizational psychology.It seems to me that the neoliberal agenda has invaded education, as it does with any uncommodified available space, and introduced the language of the market. So we get educators using the language of Silicon Valley and attempting to ‘disrupt’ their institution.However, this cohesion assumes a “shared language of inquiry,” which does not currently exist. Today’s shared language around innovation is emotive rather than procedural; we use innovation to highlight the desired positive results of our efforts rather than to identify anything specific about our effort (products, processes or policies). The predominant use of innovation is to highlight the value and future-readiness of whatever the speaker supports, which is why opposite sides of issues in education (see school choice, personalized learning, etc.) use innovation in promoting their ideologies.

If the goal of academic innovation is to be creative and flexible in the development, discovery and engagement of knowledge about the future of education, the foundation for knowledge accumulation and development needs to be innovative in and of itself. That must start with an operational definition of academic innovation, differentiating what innovation means to education from what it means to entrepreneurial spaces or sociological efforts.While I’m sympathetic to the idea that educational institutions can be ‘stodgy’ places that can often need a good kick up the behind, I’m not entirely sure that academic innovation as a discipline will do anything other than legitimise the capitalist takeover of a public good.That definition must address the negotiated history of the term, from the earliest application of the concept in government-funded research spurred by education policy during the 1960s, through overlooked innovation authors like Freeman and Thorstein Veblen. Negotiating the future we want with the history we have is vital in order to determine the best structure to support the development of an inventive network for creating research-backed, criticism-engaged and outside-the-box approaches to the future of education. The energy behind what we today call academic innovation needs to be put toward problematizing and unraveling the causes of the obstacles facing the practice of educating people of competence and character, rather than focusing on the promotion of near-future technologies and their effect on symptomatic issues.

Source: Inside Higher Ed (via Aaron Davis)

Estonia goes for free public transport

Estonia is pretty much already the home of free public wifi, so this is a logical next step. The council of the capital city, Tallinn, provided free public transport to citizens for the last five years after a referdendum. Now the idea is to extend that to everyone — including tourists.

This article mainly comprises of an interview with Allan Alaküla, the Head of Tallinn European Union Office. He makes a couple of important points:

A good thing is, of course, that it mostly appeals to people with lower to medium incomes. But free public transport also stimulates the mobility of higher-income groups. They are simply going out more often for entertainment, to restaurants, bars and cinemas. Therefore they consume local goods and services and are likely to spend more money, more often. In the end this makes local businesses thrive. It breathes new life into the city.In other words, allowing people to move around the city without thinking about the cost encourages people to do so. This has economic and social benefits.

Before introducing free public transport, the city center was crammed with cars. This situation has improved — also because we raised parking fees. When non-Tallinners leave their cars in a park-and-ride and check in to public transport on the same day, they [not] only use public transport for free, but also won’t be charged the parking fee. We noticed that people didn’t complain about high parking fees once we offered them a good alternative.This is great, joined-up thinking: make it really easy for visitors to the city to do the right thing. Estonia really is at the forefront of citizen and pro-social innovation, as anyone familiar with their e-Residency scheme will be aware.

Source: Pop-Up City

Bridging technologies

When you go deep enough into philosophy or religion one of the key insights is that everything is temporary. Success is temporary. Suffering is temporary. Your time on earth is temporary.

One way of thinking about this one a day-to-day basis is that everything is a bridge to something else. So that technology that I’ve been excited about since 2011? Yep, it’s a bridge (or perhaps a raft) to get to something else.

Benedict Evans, who works for the VC firm Andreessen Horowitz, sends out a great, short newsletter every week to around 95,000 people. I’m one of them. In this week’s missive, he linked to a blog post he wrote about bridging technologies.

A bridge product says 'of course x is the right way to do this, but the technology or market environment to deliver x is not available yet, or is too expensive, and so here is something that gives some of the same benefits but works now.'As with anything, there are good and bad bridging technologies. At the time, it can be hard to spot the difference:

It's all obvious in retrospect, as with the example of Firefox OS, which was developed at the same time I was at Mozilla:In hindsight, though, not just WAP but the entire feature-phone mobile internet prior to 2007, including i-mode, with cut-down pages and cut-down browsers and nav keys to scroll from link to link, was a bridge. The 'right' way was a real computer with a real operating system and the real internet. But we couldn't build phones that could do that in 1999, even in Japan, and i-mode worked really well in Japan for a decade.

[T]he problem with the Firefox phone project was that even if you liked the experience proposition - 'almost as good as Android but works on much cheaper phones' - the window of time before low-end Android phones closed the price gap was too short.Usually, cheap things add more features until people just 'make do' with 80-90% of the full feature set. However, that's not always the case:

Sometimes the ‘right’ way to do it just doesn’t exist yet, but often it does exist but is very expensive. So, the question is whether the ‘cheap, bad’ solution gets better faster than the ‘expensive, good’ solution gets cheap. In the broader tech industry (as described in the ‘disruption’ concept), generally the cheap product gets good. The way that the PC grew and killed specialized professional hardware vendors like Sun and SGi is a good example. However, in mobile it has tended to be the other way around - the expensive good product gets cheaper faster than the cheap bad product can get good.Evans goes on to talk about autonomous vehicles, something that he's heavily invested in (financially and intellectually) with his VC firm.

In the world of open source, however, it’s a slightly different process. Instead of thinking about the ‘runway’ of capital that you’ve got before you have to give up and go home, it’s about deciding when it no longer makes sense to maintain the project you’re working on. In some cases, the answer to that is ‘never’ which means that the project keeps going and going and going.

It can be good to have a forcing function to focus people’s minds. I’m thinking, for example, of Steve Jobs declaring war on Flash. The reasons he gives are disingenuous (accusing Adobe of not being ‘open’!) but the upshot of Apple declaring Flash as dead to them caused the entire industry to turn upside down. In effect, Flash was a ‘bridge’ to the full web on mobile devices.

Using the idea of technology ‘bridges’ in my own work can lead to some interesting conclusions. For example, the Project MoodleNet work that I’m beginning will ultimately be a bridge to something else for Moodle. Thinking about my own career, each step has been a bridge to something else; the most interesting bridges have been those where I haven’t been quite sure what was one the other side. Or, indeed, if there even was an other side…

Source: Benedict Evans

Does the world need interactive emails?

I’m on the fence on this as, on the one hand, email is an absolute bedrock of the internet, a common federated standard that we can rely upon independent of technological factionalism. On the other hand, so long as it’s built into a standard others can adopt, it could be pretty cool.

The author of this article really doesn’t like Google’s idea of extending AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages) to the inbox:

See, email belongs to a special class. Nobody really likes it, but it’s the way nobody really likes sidewalks, or electrical outlets, or forks. It not that there’s something wrong with them. It’s that they’re mature, useful items that do exactly what they need to do. They’ve transcended the world of likes and dislikes.Fair enough, but as a total convert to Google's 'Inbox' app both on the web and on mobile, I don't think we can stop innovation in this area:

Emails are static because messages are meant to be static. The entire concept of communication via the internet is based around the telegraphic model of exchanging one-way packets with static payloads, the way the entire concept of a fork is based around piercing a piece of food and allowing friction to hold it in place during transit.Are messages 'meant to be static'? I'm not so sure. Books were 'meant to' be paper-based until ebooks came along, and now there's all kinds of things we can do with ebooks that we can't do with their dead-tree equivalents.

Why do this? Are we running out of tabs? Were people complaining that clicking “yes” on an RSVP email took them to the invitation site? Were they asking to have a video chat window open inside the email with the link? No. No one cares. No one is being inconvenienced by this aspect of email (inbox overload is a different problem), and no one will gain anything by changing it.Although it's an entertaining read, if 'why do this?' is the only argument the author, Devin Coldewey, has got against an attempted innovation in this space, then my answer would be why not? Although Coldewey points to the shutdown of Google Reader as an example of Google 'forcing' everyone to move to algorithmic news feeds, I'm not sure things are, and were, as simple as that.

It sounds a little simplistic to say so, but people either like and value something and therefore use it, or they don’t. We who like and uphold standards need to remember that, instead of thinking about what people and organisations should and shouldn’t do.

Source: TechCrunch

Does the world need interactive emails?

I’m on the fence on this as, on the one hand, email is an absolute bedrock of the internet, a common federated standard that we can rely upon independent of technological factionalism. On the other hand, so long as it’s built into a standard others can adopt, it could be pretty cool.

The author of this article really doesn’t like Google’s idea of extending AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages) to the inbox:

See, email belongs to a special class. Nobody really likes it, but it’s the way nobody really likes sidewalks, or electrical outlets, or forks. It not that there’s something wrong with them. It’s that they’re mature, useful items that do exactly what they need to do. They’ve transcended the world of likes and dislikes.Fair enough, but as a total convert to Google's 'Inbox' app both on the web and on mobile, I don't think we can stop innovation in this area:

Emails are static because messages are meant to be static. The entire concept of communication via the internet is based around the telegraphic model of exchanging one-way packets with static payloads, the way the entire concept of a fork is based around piercing a piece of food and allowing friction to hold it in place during transit.Are messages 'meant to be static'? I'm not so sure. Books were 'meant to' be paper-based until ebooks came along, and now there's all kinds of things we can do with ebooks that we can't do with their dead-tree equivalents.

Why do this? Are we running out of tabs? Were people complaining that clicking “yes” on an RSVP email took them to the invitation site? Were they asking to have a video chat window open inside the email with the link? No. No one cares. No one is being inconvenienced by this aspect of email (inbox overload is a different problem), and no one will gain anything by changing it.Although it's an entertaining read, if 'why do this?' is the only argument the author, Devin Coldewey, has got against an attempted innovation in this space, then my answer would be why not? Although Coldewey points to the shutdown of Google Reader as an example of Google 'forcing' everyone to move to algorithmic news feeds, I'm not sure things are, and were, as simple as that.

It sounds a little simplistic to say so, but people either like and value something and therefore use it, or they don’t. We who like and uphold standards need to remember that, instead of thinking about what people and organisations should and shouldn’t do.

Source: TechCrunch

Game-changing modular wheels

This is fantastic:

The Revolve is a full-size 26-inch spoked wheel that can be folded to a third its diameter and 60 percent less space, and back again in an instant, and its commercial availability will offer new design possibilities for folding bicycles, folding wheelchairs and many other vehicles that need to be transported in compact form.A real game-change in terms of accessibility, I reckon.

Source: New Atlas

Game-changing modular wheels

This is fantastic:

The Revolve is a full-size 26-inch spoked wheel that can be folded to a third its diameter and 60 percent less space, and back again in an instant, and its commercial availability will offer new design possibilities for folding bicycles, folding wheelchairs and many other vehicles that need to be transported in compact form.A real game-change in terms of accessibility, I reckon.

Source: New Atlas

Succeeding with innovation projects

There’s some great advice in this article for those, like me, who are leading innovation projects in 2018:

Your role is to make noise around the idea so that potential stakeholders are excited to learn more about it. At this stage, it’s really important to reach out to key individuals within the company and ask for advice, so you can more easily establish an affiliation between them and the new activity, and cultivate a community of internal supporters.Source: TNW