- Our inability to distinguish between confidence and competence

- Our love of charasmatic individuals

- The allure of “people with grandiose visions that tap into our own narcissism”

- How does a computer ‘see’ gender? (Pew Research Center) — "Machine learning tools can bring substantial efficiency gains to analyzing large quantities of data, which is why we used this type of system to examine thousands of image search results in our own studies. But unlike traditional computer programs – which follow a highly prescribed set of steps to reach their conclusions – these systems make their decisions in ways that are largely hidden from public view, and highly dependent on the data used to train them. As such, they can be prone to systematic biases and can fail in ways that are difficult to understand and hard to predict in advance."

- The Communication We Share with Apes (Nautilus) — "Many primate species use gestures to communicate with others in their groups. Wild chimpanzees have been seen to use at least 66 different hand signals and movements to communicate with each other. Lifting a foot toward another chimp means “climb on me,” while stroking their mouth can mean “give me the object.” In the past, researchers have also successfully taught apes more than 100 words in sign language."

- Why degrowth is the only responsible way forward (openDemocracy) — "If we free our imagination from the liberal idea that well-being is best measured by the amount of stuff that we consume, we may discover that a good life could also be materially light. This is the idea of voluntary sufficiency. If we manage to decide collectively and democratically what is necessary and enough for a good life, then we could have plenty."

- 3 times when procrastination can be a good thing (Fast Company) — "It took Leonardo da Vinci years to finish painting the Mona Lisa. You could say the masterpiece was created by a master procrastinator. Sure, da Vinci wasn’t under a tight deadline, but his lengthy process demonstrates the idea that we need to work through a lot of bad ideas before we get down to the good ones."

- Why can’t we agree on what’s true any more? (The Guardian) — "What if, instead, we accepted the claim that all reports about the world are simply framings of one kind or another, which cannot but involve political and moral ideas about what counts as important? After all, reality becomes incoherent and overwhelming unless it is simplified and narrated in some way or other.

- A good teacher voice strikes fear into grown men (TES) — "A good teacher voice can cut glass if used with care. It can silence a class of children; it can strike fear into the hearts of grown men. A quiet, carefully placed “Excuse me”, with just the slightest emphasis on the “-se”, is more effective at stopping an argument between adults or children than any amount of reason."

- Freeing software (John Ohno) — "The only way to set software free is to unshackle it from the needs of capital. And, capital has become so dependent upon software that an independent ecosystem of anti-capitalist software, sufficiently popular, can starve it of access to the speed and violence it needs to consume ever-doubling quantities of to survive."

- Young People Are Going to Save Us All From Office Life (The New York Times) — "Today’s young workers have been called lazy and entitled. Could they, instead, be among the first to understand the proper role of work in life — and end up remaking work for everyone else?"

- Global climate strikes: Don’t say you’re sorry. We need people who can take action to TAKE ACTUAL ACTION (The Guardian) — "Brenda the civil disobedience penguin gives some handy dos and don’ts for your civil disobedience"

- Some of your talents and skills can cause burnout. Here’s how to identify them (Fast Company) — "You didn’t mess up somewhere along the way or miss an important lesson that the rest of us received. We’re all dealing with gifts that drain our energy, but up until now, it hasn’t been a topic of conversation. We aren’t discussing how we end up overusing our gifts and feeling depleted over time."

- Learning from surveillance capitalism (Code Acts in Education) — "Terms such as ‘behavioural surplus’, ‘prediction products’, ‘behavioural futures markets’, and ‘instrumentarian power’ provide a useful critical language for decoding what surveillance capitalism is, what it does, and at what cost."

- Facebook, Libra, and the Long Game (Stratechery) — "Certainly Facebook’s audacity and ambition should not be underestimated, and the company’s network is the biggest reason to believe Libra will work; Facebook’s brand is the biggest reason to believe it will not."

- The Pixar Theory (Jon Negroni) — "Every Pixar movie is connected. I explain how, and possibly why."

- Mario Royale (Kottke.org) — "Mario Royale (now renamed DMCA Royale to skirt around Nintendo’s intellectual property rights) is a battle royale game based on Super Mario Bros in which you compete against 74 other players to finish four levels in the top three. "

- Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think (The Atlantic) — "In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s."

- What Happens When Your Kids Develop Their Own Gaming Taste (Kotaku) — "It’s rewarding too, though, to see your kids forging their own path. I feel the same way when I watch my stepson dominate a round of Fortnite as I probably would if he were amazing at rugby: slightly baffled, but nonetheless proud."

- Whence the value of open? (Half an Hour) — "We will find, over time and as a society, that just as there is a sweet spot for connectivity, there is a sweet spot for openness. And that point where be where the default for openness meets the push-back from people on the basis of other values such as autonomy, diversity and interactivity. And where, exactly, this sweet spot is, needs to be defined by the community, and achieved as a consensus."

- How to Be Resilient in the Face of Harsh Criticism (HBR) — "Here are four steps you can try the next time harsh feedback catches you off-guard. I’ve organized them into an easy-to-remember acronym — CURE — to help you put these lessons in practice even when you’re under stress."

- Fans Are Better Than Tech at Organizing Information Online (WIRED) — "Tagging systems are a way of imposing order on the real world, and the world doesn't just stop moving and changing once you've got your nice categories set up."

- What do cats do all day? (The Kid Should See This) — "Catcam footage from collar cameras captured the activities of 16 free-roaming domestic cats in England as they explored, stared, touched noses, hunted, vocalized, and more."

- These researchers invented an entirely new way of building with wood (Fast Company) — "Each of the 12 wooden components of the tower was made by laminating two pieces of wood with different levels of moisture. Then, when the laminated pieces of wood dried out, the piece of wood curved naturally–no molds or braces needed."

- What Did Old English Sound Like? Hear Reconstructions of Beowulf, The Bible, and Casual Conversations (Open Culture) — "Over the course of 1000 years, the language came together from extensive contact with Anglo-Norman, a dialect of French; then became heavily Latinized and full of Greek roots and endings; then absorbed words from Arabic, Spanish, and dozens of other languages, and with them, arguably, absorbed concepts and pictures of the world that cannot be separated from the language itself."

- Adversarial interoperability: reviving an elegant weapon from a more civilized age to slay today's monopolies (BoingBoing) — "This kind of adversarial interoperability goes beyond the sort of thing envisioned by "data portability," which usually refers to tools that allow users to make a one-off export of all their data, which they can take with them to rival services. Data portability is important, but it is no substitute for the ability to have ongoing access to a service that you're in the process of migrating away from."

- Fables of School Reform (The Baffler) — "Even pre-internet efforts to upgrade the technological prowess of American schools came swathed in the quasi-millennial promise of complete school transformation."

- Apple created the privacy dystopia it wants to save you from (Fast Company) — I'm not sure I agree with either the title or subtitle of this piece, but it raises some important points.

- When Grown-Ups Get Caught in Teens’ AirDrop Crossfire (The Atlantic) — hilarious and informative in equal measure!

- Anxiety, revolution, kidnapping: therapy secrets from across the world (The Guardian) — a fascinating look at the reasons why people in different countries get therapy.

- Post-it note war over flowers deemed ‘most middle-class argument ever’ (Metro) — amusing, but there's important things to learn from this about private/public spaces.

- Modern shamans: Financial managers, political pundits and others who help tame life’s uncertainty (The Conversation) — a 'cognitive anthropologist' explains the role of shamans in ancient societies, and extends the notion to the modern world.

Adversarial interoperability to return to a world of 'fast companies'

Cory Doctorow is one of my favourite people on the entire planet. I’ve heard him speak in person and online on numerous occasions. I met him a couple of times while at Mozilla, and he’s even recommended swimming pools in Toronto to me when I visited. (He’s a daily swimmer due to chronic back pain.)

His new book, which I’m saving to read for my next holiday, is The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of Computation. In this interview as part of promoting the book, he talks about how we’ve ended up in a world without real competition in the technology marketplace. Essential reading, as ever.

There used to be a time when the tech sector could be described as a bunch of “fast companies,” right? They would use the interoperability that’s latent in all digital technology and they would specifically target whatever pain points the incumbent had introduced. If incumbents were making money by showing you ads, they made an ad blocker. If incumbents were making money by charging gigantic margins on hard drives, they made cheaper hard drives.Source: Cory Doctorow: Silicon Valley is now a world of ‘lumbering behemoths’ | Fast CompanyOver time, we went from an internet where tech companies more or less had their users’ backs, to an internet where tech companies are colluding to take as big a bite as possible out of those users. We do not have fast companies anymore; we have lumbering behemoths. If you’ve started a fast company, it’s probably just a fake startup that you’re hoping to get acqui-hired by one of the big giants, which is something that used to be illegal.

As these companies grew more concentrated, they were able to collude and convince courts and regulators and lawmakers that it was time to get rid of the kind of interoperability, the reverse engineering that had been a feature of technology since the very beginning, and move into a new era in which no one was allowed to do anything to a tech platform that their shareholders wouldn’t appreciate. And that the government should step in to use the state’s courts to punish anyone who disagrees. That’s how we got to the world that we’re in today.

Leadership is contextual

This article feels quite foreign to me as a member of a co-operative, but it contains an important insight. I feel that there’s more nuance than the author provides, in that leadership is contextual.

Some people believe that they are a ‘leader’ because their job title says so. But true leadership comes when people choose to follow you, not be coerced into something because you’re higher up the pyramid than they are.

For as long as I can remember, leadership was the expectation. If you wanted to move up in the world, you had to be a leader: in school, at work, in your extracurriculars. Leadership was the golden ticket, and the more opportunities you took, the closer you’d get to owning the whole chocolate factory.Source: What to do if you don't want to be a leader | Fast Company

AI-generated misinformation is getting more believable, even by experts

I’ve been using thispersondoesnotexist.com for projects recently and, honestly, I wouldn’t be able to tell that most of the faces it generates every time you hit refresh aren’t real people.

For every positive use of this kind of technology, there are of course negatives. Misinformation and disinformation is everywhere. This example shows how even experts in critical fields such as cybersecurity, public safety, and medicine can be fooled, too.

If you use such social media websites as Facebook and Twitter, you may have come across posts flagged with warnings about misinformation. So far, most misinformation—flagged and unflagged—has been aimed at the general public. Imagine the possibility of misinformation—information that is false or misleading—in scientific and technical fields like cybersecurity, public safety, and medicine.There is growing concern about misinformation spreading in these critical fields as a result of common biases and practices in publishing scientific literature, even in peer-reviewed research papers. As a graduate student and as faculty members doing research in cybersecurity, we studied a new avenue of misinformation in the scientific community. We found that it’s possible for artificial intelligence systems to generate false information in critical fields like medicine and defense that is convincing enough to fool experts.Source: False, AI-generated cybersecurity news was able to fool experts | Fast Company

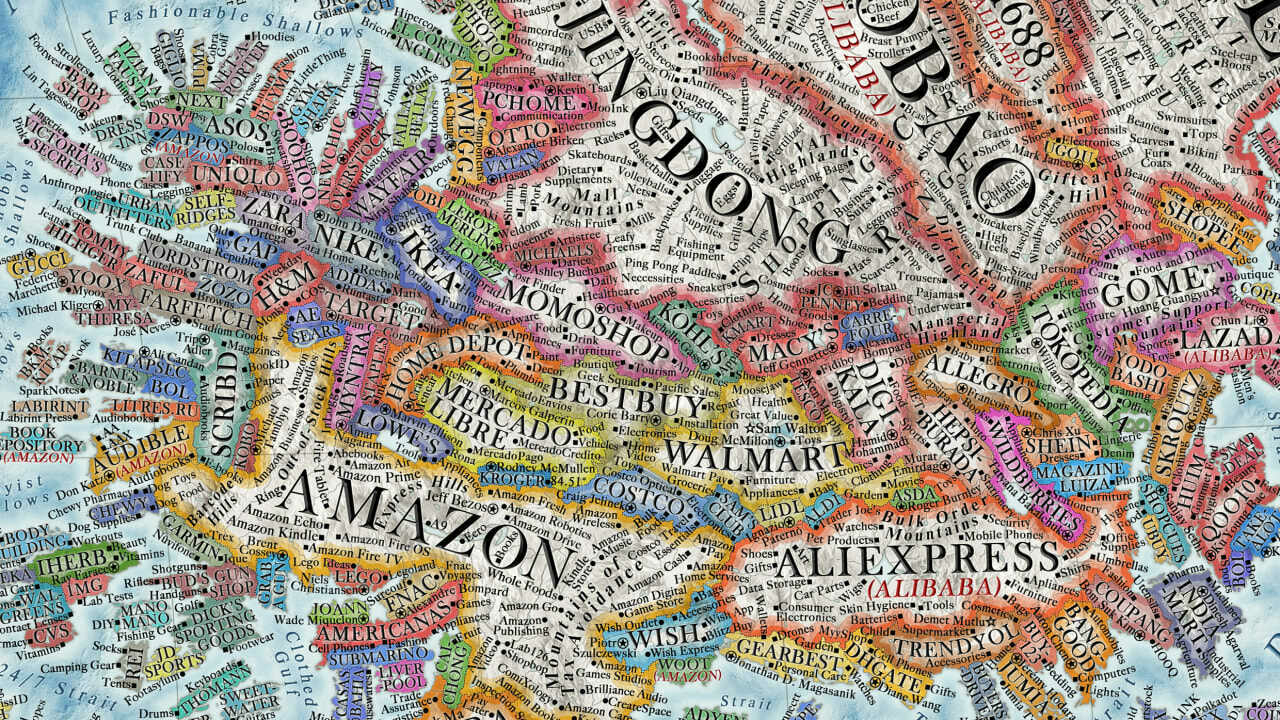

The world's most popular websites, mapped

Years ago, iA had a map of the web which was much smaller and less intricate than this. My son had it up on his bedroom wall. The digital world is a lot more complex and a lot less English-speaking that it once was!

“As internet access has spread rapidly throughout developing countries in the last decade, the popularity of non-English websites has increased considerably—about a third of the world’s most visited 50 websites are based in China, with Tmall, QQ, Baidu, or Sohu surpassing Amazon, Yahoo, and even Facebook in terms of traffic,” Vargic says. “There is also a much larger [number] of popular Indonesian, Indian, Iranian, Brazilian, and other sites than even [a few] years ago.”Source: Think you know the world's most popular websites? Think again | Fast Company

Digital fashion is another example of a nascent industry beset with inequalities

As the conclusion to this article states, if digital fashion industry doesn’t differentiate itself from IRL fashion now, it’s storing up problems for the future.

If one of the main arguments in support of digital fashion is its ability to serve the marginalized, what happens when its development is in the hands of those with overwhelmingly socio-economically privileged backgrounds? The Institute of Digital Fashion (IoDF), a digital fashion studio and retailer, weighed in on why these issues are major obstacles to the healthy advancement of the industry in an online interview. “The industry’s biggest challenges are the current traps of the IRL fashion industry. In brief, if we mirror these, we are lost!” its founders state. Recognizing these issues, founders Cattytay and Leanne Elliott Young are taking steps to help it develop on a socially conscious path.Source: Everyone from Gucci to Louis Vuitton is betting on digital fashion. Here’s why they should proceed with caution | Fast Company

Mastering a 5,400-character typewriter

I can’t even imagine how difficult this must have been to type on!

The IBM Chinese typewriter was a formidable machine—not something just anyone could handle with the aplomb of the young typist in the film. On the keyboard affixed to the hulking, gunmetal gray chassis, 36 keys were divided into four banks: 0 through 5; 0 through 9; 0 through 9; and 0 through 9. With just these 36 keys, the machine was capable of producing up to 5,400 Chinese characters in all, wielding a language that was infinitely more difficult to mechanize than English or other Western writing systems.Source: How Lois Lew mastered IBM’s 1940s Chinese typewriterTo type a Chinese character, one depressed a total of 4 keys—one from each bank—more or less simultaneously, compared by one observer to playing a chord on the piano. Just as the film explained, “if you want to type word number 4862 you would press 4-8-6-2 and the machine would type the right character.”

Each four-digit code corresponded with a character etched on a revolving drum inside the typewriter. Spinning continuously at a speed of 60 revolutions per minute, or once per second, the drum measured 7 inches in diameter, and 11 inches in length. Its surface was etched with 5,400 Chinese characters, letters of the English alphabet, punctuation marks, numerals, and a handful of other symbols.

Pandemic microaggressions

This article primarily focuses on racism and intolerance to gender differences, but even as a "white, male... heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied, wealthy, and educated" man, I recognise some of what it describes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has opened much of our workforce to a new surge of microaggressions by making coworkers as unwelcome guests in their homes through video meetings. Bosses and coworkers can see our families and furniture. They can hear the background noise from our neighborhoods. They see us with our hair, faces, and clothes less put together than usual due to the closure of the shops and salons that help us assimilate into the mainstream world.

Sarah Morgan, How microaggressions look different when we’re working remotely (Fast Company)

There's a line, I think between friendly banter and curiosity and, for example, being reminded on a daily basis that I'm getting ever more grey, that I'm looking tired, and my forehead is shinier than a billiard ball.

Microaggressions? Perhaps. But on days when I'm not feeling 100%, it sure does grind me down.

How you do anything is how you do everything

So said Derek Sivers, although I suspect that, originally, it's probably a core principle of Zen Buddhism. In this article I want to talk about management and leadership. But also about emotional intelligence and integrity.

I currently spend part of my working life as a Product Manager. At some organisations, this means that you're in charge of the budget, and pull in colleagues from different disciplines. For example, a designer you're working with on a particular project might report to the Head of UX. Matrix-style management and internal budgeting keeps track of everything.

This approach can get complicated so, at other companies (like the one I'm working with), the Product Manager manages both people and product. It's a lot of work, as both can be complicated.

I think I'm OK at managing people, and other people say I'm good at it, but it's not my favourite thing in the world to do.

That's why, when hiring, I try to do so in one of three ways. Ideally, I want to hire people with whom at least one member of the existing team has already worked and can vouch for. If that doesn't work, then I'm looking for people vouched for my the networks of which the team are part. Failing that, I'm trying to find people who don't wait for direction, but know how to get on with things that need doing.

It's an approach I've developed from the work of Laura Thomson. She's a former colleague at Mozilla, and an advocate of a chaordic style of management and self-organising ducks:

Instead of having ‘all your ducks in a row’ the analogy in chaordic management is to have ‘self-organising ducks’. The idea is to give people enough autonomy, knowledge and skill to be able to do the management themselves.

As I've said before, the default way of organising human beings is hierarchy. That doesn't mean it's the best way. Hierachy tends to lean on processes, paperwork and meetings to 'get things done' but even a cursory glance at Open Source projects shows that all of this isn't strictly necessary.

Last week, a new-ish member of the team said that I can be "too nice". I'm still processing that and digging into what they meant, but I then ended up reading an article by Roddy Millar for Fast Company entitled Here’s why being likable may make you a less effective leader.

It's a slightly oddly-framed article that quotes Prof. Karen Cates from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management :

Leaders should not put likability above effectiveness. There are times when the humor and smiles need to go and a let’s-get-this-done approach is required. Cates goes further: “Even the ‘nasty boss approach’ can be really effective—but in short, small doses—to get everyone’s attention and say ‘Hey, we’ve got to make some changes around here.’ You can then create—with an earnest approach—that more likable persona as you move forward. Likability is a good thing to have in your leadership toolkit, but it shouldn’t be the biggest hammer in the box.”

Roddy Millar

I think there's a difference between 'trying to be likeable' and 'treating your colleagues with dignity and respect'.

If you're being nice to be just to liked by your team, you're probably doing it wrong. It's a bit like, back when I was teaching, teachers who wanted to be liked by the kids they taught.

The other approach is to simply treat the people around you with dignity and respect, realising that all of human life involves suffering, so let's not add to the burden through our everyday working lives.

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The above is one of my favourite quotations. We don't need to crack the whip or wield some kind of totem of hierarchical power over other people. We just need to ensure people are in the right place (physically and emotoinally), with the right things (tools, skills, and information) to get things done.

In managers are for caring, Harold Jarche points a finger at hierarchical organisations, stating that they are "what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator".

Jarche wonders instead what would happen if they were structured more like communities of practice?

What would an organization look like with looser hierarchies and stronger networks? A lot more human, retrieving some of the intimacy and cooperation of tribal groups. We already have other ways of organizing work. Orchestras are not teams, and neither are jazz ensembles. There may be teamwork on a theatre production but the cast is not a team. It is more like a community of practice, with strong and weak social ties.

Harold Jarche

I think part of the problem, to be honest, is emotional intelligence, or rather the lack of it, in many organisations.

Unfortunately, the way to earn more money in organisations is to start managing people. Which is fine for the subset of people who have the skills to be able to handle this. For others, it's a frustrating experience that takes them away from doing the work.

For TED Ideas, organisational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic asks Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? And what can we do about it? He lists three reasons why we have so many incompetent (male) leaders:

He suggests three ways to fix this. The other two are all well and good, but I just want to focus on the first solution he suggests:

The first solution is to follow the signs and look for the qualities that actually make people better leaders. There is a pathological mismatch between the attributes that seduce us in a leader and those that are needed to be an effective leader. If we want to improve the performance of our leaders, we should focus on the right traits. Instead of falling for people who are confident, narcissistic and charismatic, we should promote people because of competence, humility and integrity. Incidentally, this would also lead to a higher proportion of female than male leaders — large-scale scientific studies show that women score higher than men on measures of competence, humility and integrity. But the point is that we would significantly improve the quality of our leaders.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

The best leaders I've worked for exhibited high levels of emotional intelligence. Most of them were women.

Developing emotional intelligence is difficult and goodness knows I'm no expert. What I think we perhaps need to do is to remove our corporate dependency on hierarchy. In hierarchies, emotion and trust is removed as an impediment to action.

However, in my experience, hierarchy is inherently patriarchal and competitive. It's not something that's necessarily useful in every industry in the 21st century. And hierarchies are not places that I, and people like me, particularly thrive.

Instead, I think we require trust-based ways of organising — ways that emphasis human relationships. I think these are also more conducive to human flourishing.

Right now, approaches such as sociocracy take a while to get our collective heads around as they're opposed to our "default operating system" of hierarchy. However, over time I think we'll see versions of this becoming the norm, as it becomes ever easier to co-ordinate people at a distance.

To sum up, what it means to be an effective leader is changing. Returning to the article cited above by Harold Jarche, he writes:

Hierarchical teams are what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator. In a creative economy, the unity of hierarchical teams is counter-productive, as it shuts off opportunities for serendipity and innovation. In a complex and networked economy workers need more autonomy and managers should have less control.

Harold Jarche

Many people no longer live in a world of the 'permanent job' and 'career ladder'. What counts as success for them is not necessarily a steadily-increasing paycheck, but measures such as social justice or 'making a dent in the universe'. This is where hierarchy fails, and where emergent, emotionally-intelligent leaders with teams of self-organising ducks, thrive.

Technology is the name we give to stuff that doesn't work properly yet

So said my namesake Douglas Adams. In fact, he said lots of wise things about technology, most of them too long to serve as a title.

I'm in a weird place, emotionally, at the moment, but sometimes this can be a good thing. Being taken out of your usual 'autopilot' can be a useful way to see things differently. So I'm going to take this opportunity to share three things that, to be honest, make me a bit concerned about the next few years...

Attempts to put microphones everywhere

In an article for Slate, Shannon Palus ranks all of Amazon's new products by 'creepiness'. The Echo Frames are, in her words:

A microphone that stays on your person all day and doesn’t look like anything resembling a microphone, nor follows any established social codes for wearable microphones? How is anyone around you supposed to have any idea that you are wearing a microphone?

Shannon Palus

When we're not talking about weapons of mass destruction, it's not the tech that concerns me, but the context in which the tech is used. As Palus points out, how are you going to be able to have a 'quiet word' with anyone wearing glasses ever again?

It's not just Amazon, of course. Google and Facebook are at it, too.

Full-body deepfakes

With the exception, perhaps, of populist politicians, I don't think we're ready for a post-truth society. Check out the video above, which shows Chinese technology that allows for 'full body deepfakes'.

The video is embedded, along with a couple of others in an article for Fast Company by DJ Pangburn, who also notes that AI is learning human body movements from videos. Not only will you be able to prank your friends by showing them a convincing video of your ability to do 100 pull-ups, but the fake news it engenders will mean we can't trust anything any more.

Neuromarketing

If you clicked on the 'super-secret link' in Sunday's newsletter, you will have come across STEALING UR FEELINGS which is nothing short of incredible. As powerful as it is in showing you the kind of data that organisations have on us, it's the tip of the iceberg.

Kaveh Waddell, in an article for Axios, explains that brains are the last frontier for privacy:

"The sort of future we're looking ahead toward is a world where our neural data — which we don't even have access to — could be used" against us, says Tim Brown, a researcher at the University of Washington Center for Neurotechnology.

Kaveh Waddell

This would lead to 'neuromarketing', with advertisers knowing what triggers and influences you better than you know yourself. Also, it will no doubt be used for discriminatory purposes and, because it's coming directly from your brainwaves, short of literally wearing a tinfoil hat, there's nothing much you can do.

So there we are. Am I being too fearful here?

Saturday strikings

This week's roundup is going out a day later than usual, as yesterday was the Global Climate Strike and Thought Shrapnel was striking too!

Here's what I've been paying attention to this week:

To refrain from imitation is the best revenge

Today's title comes from Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, which regular readers of my writing will know I read on repeat. George Herbert, the English poet, wrote something similar to this in "living well is the best revenge".

But what do these things actually mean in practice?

One of my favourite episodes of Frasier (the only sitcom I've ever really enjoyed) is when Niles has to confront his childhood bully. It leads to this magnificent exchange:

Frasier:

You know the expression, "Living well is the best revenge"?

Niles:

It's a wonderful expression. I just don't know how true it is. You don't see it turning up in a lot of opera plots. "Ludwig, maddened by the poisoning of his entire family, wreaks vengeance on Gunther in the third act by living well."

Frasier:

All right, Niles.

Niles:

"Whereupon Woton, upon discovering his deception, wreaks vengeance on Gunther in the third act again by living even better than the Duke."

Frasier:

Oh, all right!

In other words, it often doesn't feel that 'living well' makes any tangible difference.

But let's step back a moment. What does it mean to 'live well'? Is it the same as refraining from imitating others, or are Marcus Aurelius and George Herbert talking about two entirely different things?

During an email exchange last week, someone mentioned that they weren't sure whether my segues between topics were 'brilliant' or 'tenuous'. Well, dear reader, here's a chance to judge for yourself....

In a recent article for Fast Company, ostensibly about 'personal branding' Trip O'Dell gets awfully deep awfully quickly and starts invoking Aristotle:

Aristotle is the father of Western philosophy because he didn’t focus on likes, engagement, or followers. Aristotle focused on the nature of authenticity; what it means to be real but also persuasive. He broke the requirements for persuasiveness into four simple elements: ethos (reputation/authority), logos (logic), pathos (feeling), and kairos (timing). Those four elements are required to argue persuasively in any context. However, the stakes are higher in business. Confidently communicating who you are, what you stand for, and why you’re great at what you do is not only essential, it’s liberating.

Trip O'Dell

What I particularly like about the article is the re-focusing on 'personal ethos' rather than 'personal brand'. Branding is a form of marketing, of changing the surface appearance of something. It's about morphing a product (in this case, yourself) into something that better fits in with what other people expect.

An ethos runs much deeper. It is, as Aristotle noted, about your reputation or authority, neither of which are manufactured overnight.

The hardest part of establishing a professional ethos is describing it; it takes work, and it isn’t easy. The process requires a level of maturity and self-awareness that can be uncomfortable at times. You’re forced to ask some essential questions and make yourself vulnerable to critique and rejection. That discomfort is the tax that is paid to eliminate self-defeating habits that hold many people back in their professional lives.

Trip O'Dell

This is where that magnificent word 'authenticity' comes in. No-one really knows what it means, but everyone wants to have it. I'd argue that authenticity is a by-product of reputation and authority. Easy to destroy, difficult to build.

Let me set my stall out by saying that I think that Marcus Aurelius ("To refrain from imitation is the best revenge") and George Herbert ("Living well is the best revenge") were actually talking about much the same thing.

I don't know much about George Herbert, but Wikipedia tells me he was an orator as well as a poet, and fluent in Latin and Greek. So I'm surmising that he at least had a passing knowledge of the Stoics. The chances are he was using his poetic flair to make Marcus Aurelius' quotation a little more memorable.

Revenge can be dramatic and explosive. It can be as subtle as tiny daggers. Either way, revenge involves communicating something to another person in such a way that they realise you've got one up on them.

Malice may or may not be involved; it's probably better if it isn't. The pop diva Mariah Carey is the queen of this, claiming that she "doesn't know" people with whom she's allegedly having a feud.

But, back to the dead white dudes. In How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, Donald Robertson explains that the Stoics saw that both way we live and the way we communicate as important.

The Stoics realized that to communicate wisely, we must phrase things appropriately. Indeed, according to Epictetus, the most striking characteristic of Socrates was that he never became irritated during an argument. He was always polite and refrained from speaking harshly even when others insulted him. He patiently endured much abuse and yet was able to put an end to most quarrels in a calm and rational manner.

Donald J. Robertson

In other words, you don't need to imitate other people's anger, irritability, or lack of patience. You can 'live well' by being comfortable in your own skin and demonstrate the calm waters of your soul.

This, of course, is hard work. Nietzsche is famously quoted as saying:

He who fights too long against dragons becomes a dragon himself; and if you gaze too long into the abyss, the abyss will gaze into you.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

Feel free to substitute 'internet trolls' or 'petty-minded neighbours' for 'dragons'. The effect is the same. Marcus Aurelius is reminding us that refraining from imitating their behaviour is the best form of revenge.

Likewise, George Herbert is telling us that 'living well' is (as Trip O'Dell notes in that Fast Company article) about having a 'personal ethos'. It's about knowing who you are and where you're going. And, potentially, acting like Mariah Carey, throwing shade on your enemies by not acknowledging their existence.

Friday feeds

These things caught my eye this week:

Header image via Dilbert

Friday feastings

These are things I came across that piqued my attention:

Friday fathomings

I enjoyed reading these:

Image via Indexed