- How does a computer ‘see’ gender? (Pew Research Center) — "Machine learning tools can bring substantial efficiency gains to analyzing large quantities of data, which is why we used this type of system to examine thousands of image search results in our own studies. But unlike traditional computer programs – which follow a highly prescribed set of steps to reach their conclusions – these systems make their decisions in ways that are largely hidden from public view, and highly dependent on the data used to train them. As such, they can be prone to systematic biases and can fail in ways that are difficult to understand and hard to predict in advance."

- The Communication We Share with Apes (Nautilus) — "Many primate species use gestures to communicate with others in their groups. Wild chimpanzees have been seen to use at least 66 different hand signals and movements to communicate with each other. Lifting a foot toward another chimp means “climb on me,” while stroking their mouth can mean “give me the object.” In the past, researchers have also successfully taught apes more than 100 words in sign language."

- Why degrowth is the only responsible way forward (openDemocracy) — "If we free our imagination from the liberal idea that well-being is best measured by the amount of stuff that we consume, we may discover that a good life could also be materially light. This is the idea of voluntary sufficiency. If we manage to decide collectively and democratically what is necessary and enough for a good life, then we could have plenty."

- 3 times when procrastination can be a good thing (Fast Company) — "It took Leonardo da Vinci years to finish painting the Mona Lisa. You could say the masterpiece was created by a master procrastinator. Sure, da Vinci wasn’t under a tight deadline, but his lengthy process demonstrates the idea that we need to work through a lot of bad ideas before we get down to the good ones."

- Why can’t we agree on what’s true any more? (The Guardian) — "What if, instead, we accepted the claim that all reports about the world are simply framings of one kind or another, which cannot but involve political and moral ideas about what counts as important? After all, reality becomes incoherent and overwhelming unless it is simplified and narrated in some way or other.

- A good teacher voice strikes fear into grown men (TES) — "A good teacher voice can cut glass if used with care. It can silence a class of children; it can strike fear into the hearts of grown men. A quiet, carefully placed “Excuse me”, with just the slightest emphasis on the “-se”, is more effective at stopping an argument between adults or children than any amount of reason."

- Freeing software (John Ohno) — "The only way to set software free is to unshackle it from the needs of capital. And, capital has become so dependent upon software that an independent ecosystem of anti-capitalist software, sufficiently popular, can starve it of access to the speed and violence it needs to consume ever-doubling quantities of to survive."

- Young People Are Going to Save Us All From Office Life (The New York Times) — "Today’s young workers have been called lazy and entitled. Could they, instead, be among the first to understand the proper role of work in life — and end up remaking work for everyone else?"

- Global climate strikes: Don’t say you’re sorry. We need people who can take action to TAKE ACTUAL ACTION (The Guardian) — "Brenda the civil disobedience penguin gives some handy dos and don’ts for your civil disobedience"

- Reactionary neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, within an exclusionary vision of a racist, patriarchal, and homophobic society.

- Progressive neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, while using the banner of 'diversity' to assimilate equality and meritocracy.

- The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education (Highline) — "As our most trusted universities continue to privatize large swaths of their academic programs, their fundamental nature will be changed in ways that are hard to reverse. The race for profits will grow more heated, and the social goal of higher education will seem even more like an abstraction."

- Social Peacocking and the Shadow (Caterina Fake) — "Social peacocking is life on the internet without the shadow. It is an incomplete representation of a life, a half of a person, a fraction of the wholeness of a human being."

- Why and How Capitalism needs to be reformed (Economic Principles) — "The problem is that capitalists typically don’t know how to divide the pie well and socialists typically don’t know how to grow it well."

Friday fumings

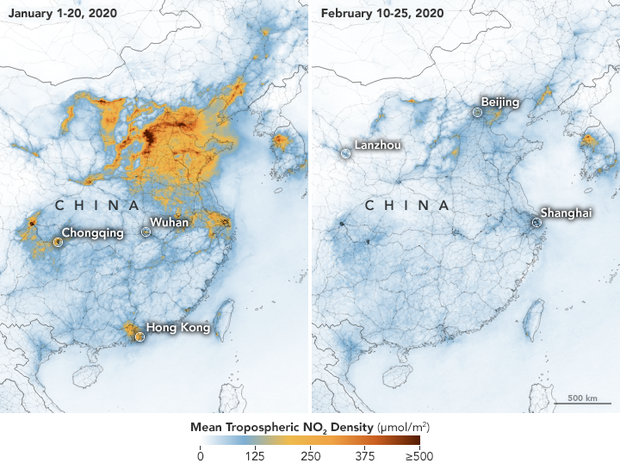

My bet is that you've spent most of this week reading news about the global pandemic. Me too. That's why I decided to ensure it's not mentioned at all in this week's link roundup!

Let me know what resonates with you... 😷

Finding comfort in the chaos: How Cory Doctorow learned to write from literally anywhere

My writing epiphany — which arrived decades into my writing career — was that even though there were days when the writing felt unbearably awful, and some when it felt like I was mainlining some kind of powdered genius and sweating it out through my fingertips, there was no relation between the way I felt about the words I was writing and their objective quality, assessed in the cold light of day at a safe distance from the day I wrote them. The biggest predictor of how I felt about my writing was how I felt about me. If I was stressed, underslept, insecure, sad, hungry or hungover, my writing felt terrible. If I was brimming over with joy, the writing felt brilliant.

Cory Doctorow (CBC)

Such great advice in here from the prolific Cory Doctorow. Not only is he a great writer, he's a great speaker, too. I think both come from practice and clarity of thought.

Slower News

Trends, micro-trends & edge cases.

This is a site that specialises in important and interesting news that is updated regularly, but not on an hour-by-hour (or even daily) basis. A wonderful antidote to staring at your social media feed for updates!

SCARF: The 5 key ingredients for psychological safety in your team

There’s actually a mountain of compelling evidence that the single most important ingredient for healthy, high-performing teams is simple: it’s trust. When Google famously crunched the data on hundreds of high-performing teams, they were surprised to find that one variable mattered more than any other: “emotional safety.” Also known as: “psychological security.” Also known as: trust.

Matt Thompson

I used to work with Matt at Mozilla, and he's a pretty great person to work alongside. He's got a book coming out this year, and Laura (another former Mozilla colleague, but also a current co-op colleague!) drew my attention to this.

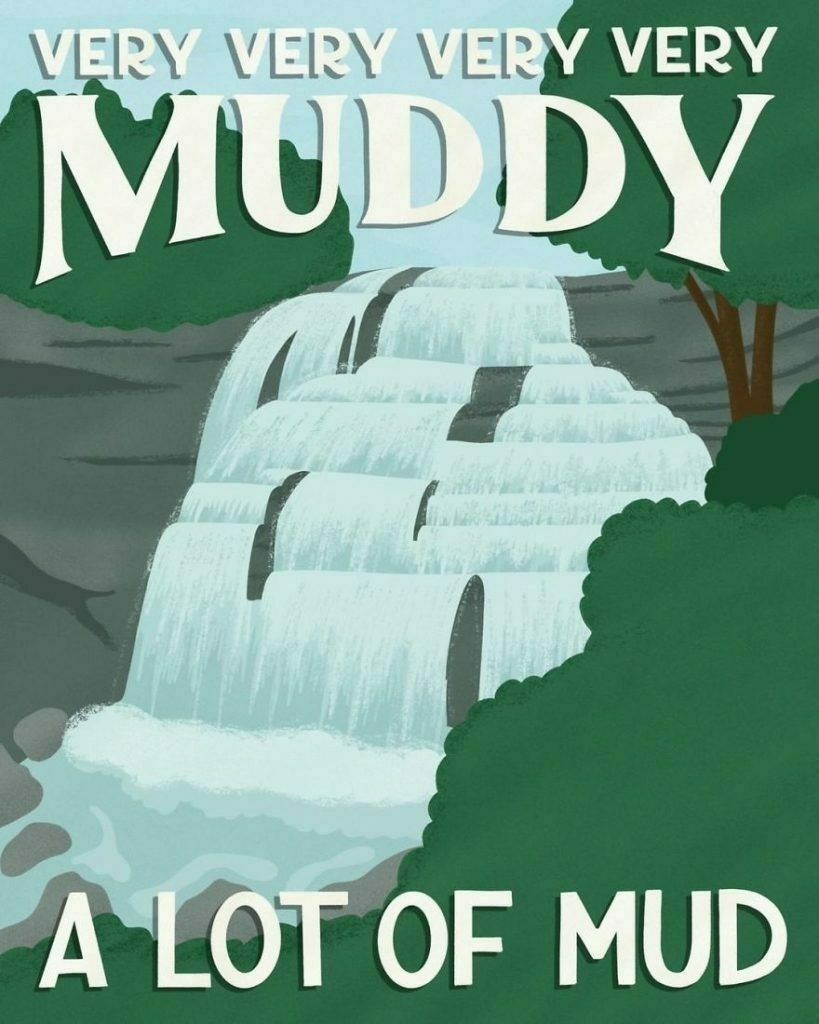

I Illustrated National Parks In America Based On Their Worst Review And I Hope They Will Make You Laugh (16 Pics)

I'm an illustrator and I have always had a personal goal to draw all 62 US National Parks, but I wanted to find a unique twist for the project. When I found that there are one-star reviews for every single park, the idea for Subpar Parks was born. For each park, I hand-letter a line from the one-star reviews alongside my illustration of each park as my way of putting a fun and beautiful twist on the negativity.

Amber Share (Bored Panda)

I love this, especially as the illustrations are so beautiful and the comments so banal.

What Does a Screen Do?

We know, for instance, that smartphone use is associated with depression in teens. Smartphone use certainly could be the culprit, but it’s also possible the story is more complicated; perhaps the causal relationship works the other way around, and depression drives teenagers to spend more time on their devices. Or, perhaps other details about their life—say, their family background or level of physical activity—affect both their mental health and their screen time. In short: Human behavior is messy, and measuring that behavior is even messier.

Jane C. Hu (Slate)

This, via Ian O'Byrne, is a useful read for anyone who deals with kids, especially teenagers.

13 reads to save for later: An open organization roundup

For months, writers have been showering us with multiple, ongoing series of articles, all focused on different dimensions of open organizational theory and practice. That's led to to a real embarrassment of riches—so many great pieces, so little time to catch them all.

So let's take moment to reflect. If you missed one (or several) now's your chance to catch up.

Bryan Behrenshausen (Opensource.com)

I've already shared some of the articles in this roundup, but I encourage you to check out the rest, and subscribe to opensource.com. It's a great source of information and guidance.

It Doesn’t Matter If Anyone Exists or Not

Capitalism has always transformed people into latent resources, whether as labor to exploit for making products or as consumers to devour those products. But now, online services make ordinary people enact both roles: Twitter or Instagram followers for conversion into scrap income for an influencer side hustle; Facebook likes transformed into News Feed-delivery refinements; Tinder swipes that avoid the nuisance of the casual encounters that previously fueled urban delight. Every profile pic becomes a passerby—no need for an encounter, even.

Ian Bogost (The Atlantic)

An amazing piece of writing, in which Ian Bogost not only surveys previous experiences with 'strangers' but applies it to the internet. As he points out, there is a huge convenience factor in not knowing who made your sandwich. I've pointed out before that capitalism is all about scale, and at the end of the day, caring doesn't scale, and scaling doesn't care.

You don't want quality time, you want garbage time

We desire quality moments and to make quality memories. It's tempting to think that we can create quality time just by designating it so, such as via a vacation. That generally ends up backfiring due to our raised expectations being let down by reality. If we expect that our vacation is going to be perfect, any single mistake ruins the experience

In contrast, you are likely to get a positive surprise when you have low expectations, which is likely the case during a "normal day". It’s hard to match perfection, and easy to beat normal. Because of this, it's more likely quality moments come out of chance

If you can't engineer quality time, and it's more a matter of random events, it follows that you want to increase how often such events happen. You can't increase the probability, but you can increase the duration for such events to occur. Put another way, you want to increase quantity of time, and not engineer quality time.

Leon Lin (Avoid boring people)

There's a lot of other interesting-but-irrelevant things in this newsletter, so scroll to the bottom for the juicy bit. I've quoted the most pertinent point, which I definitely agree with. There's wisdom in Gramsci's quotation about having "pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will".

The Prodigal Techbro

The prodigal tech bro doesn’t want structural change. He is reassurance, not revolution. He’s invested in the status quo, if we can only restore the founders’ purity of intent. Sure, we got some things wrong, he says, but that’s because we were over-optimistic / moved too fast / have a growth mindset. Just put the engineers back in charge / refocus on the original mission / get marketing out of the c-suite. Government “needs to step up”, but just enough to level the playing field / tweak the incentives. Because the prodigal techbro is a moderate, centrist, regular guy. Dammit, he’s a Democrat. Those others who said years ago what he’s telling you right now? They’re troublemakers, disgruntled outsiders obsessed with scandal and grievance. He gets why you ignored them. Hey, he did, too. He knows you want to fix this stuff. But it’s complicated. It needs nuance. He knows you’ll listen to him. Dude, he’s just like you…

Maria Farrell (The Conversationalist)

Now that we're experiencing something of a 'techlash' it's unsurprising that those who created surveillance capitalism have had a 'road to Damascus' experience. That doesn't mean, as Maria Farrell points out, that we should all of a sudden consider them to be moral authorities.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup, become a supporter, or download Thought Shrapnel Vol.1: Personal Productivity!

It’s not a revolution if nobody loses

Thanks to Clay Shirky for today's title. It's true, isn't it? You can't claim something to be a true revolution unless someone, some organisation, or some group of people loses.

I'm happy to say that it's the turn of some older white men to be losing right now, and particularly delighted that those who have spent decades abusing and repressing people are getting their comeuppance.

Enough has been written about Epstein and the fallout from it. You can read about comments made by Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation, in this Washington Post article. I've only met RMS (as he's known) in person once, at the Indie Tech Summit five years ago, but it wasn't a great experience. While I'm willing to cut visionary people some slack, he mostly acted like a jerk.

RMS is a revered figure in Free Software circles and it's actually quite difficult not to agree with his stance on many political and technological matters. That being said, he deserves everything he gets though for the comments he made about child abuse, for the way he's treated women for the past few decades, and his dictator-like approach to software projects.

In an article for WIRED entitled Richard Stallman’s Exit Heralds a New Era in Tech, Noam Cohen writes that we're entering a new age. I certainly hope so.

This is a lesson we are fast learning about freedom as it promoted by the tech world. It is not about ensuring that everyone can express their views and feelings. Freedom, in this telling, is about exclusion. The freedom to drive others away. And, until recently, freedom from consequences.

After 40 years of excluding those who didn’t serve his purposes, however, Stallman finds himself excluded by his peers. Freedom.

Maybe freedom, defined in this crude, top-down way, isn’t the be-all, end-all. Creating a vibrant inclusive community, it turns out, is as important to a software project as a coding breakthrough. Or, to put it in more familiar terms—driving away women, investing your hopes in a single, unassailable leader is a critical bug. The best patch will be to start a movement that is respectful, inclusive, and democratic.

Noam Cohen

One of the things that the next leaders of the Free Software Movement will have to address is how to take practical steps to guarantee our basic freedoms in a world where Big Tech provides surveillance to ever-more-powerful governments.

Cory Doctorow is an obvious person to look to in this regard. He has a history of understanding what's going on and writing about it in ways that people understand. In an article for The Globe and Mail, Doctorow notes that a decline in trust of political systems and experts more generally isn't because people are more gullible:

40 years of rising inequality and industry consolidation have turned our truth-seeking exercises into auctions, in which lawmakers, regulators and administrators are beholden to a small cohort of increasingly wealthy people who hold their financial and career futures in their hands.

[...]

To be in a world where the truth is up for auction is to be set adrift from rationality. No one is qualified to assess all the intensely technical truths required for survival: even if you can master media literacy and sort reputable scientific journals from junk pay-for-play ones; even if you can acquire the statistical literacy to evaluate studies for rigour; even if you can acquire the expertise to evaluate claims about the safety of opioids, you can’t do it all over again for your city’s building code, the aviation-safety standards governing your next flight, the food-safety standards governing the dinner you just ordered.

Cory Doctorow

What's this got to do with technology, and in particular Free Software?

Big Tech is part of this problem... because they have monopolies, thanks to decades of buying nascent competitors and merging with their largest competitors, of cornering vertical markets and crushing rivals who won't sell. Big Tech means that one company is in charge of the social lives of 2.3 billion people; it means another company controls the way we answer every question it occurs to us to ask. It means that companies can assert the right to control which software your devices can run, who can fix them, and when they must be sent to a landfill.

These companies, with their tax evasion, labour abuses, cavalier attitudes toward our privacy and their completely ordinary human frailty and self-deception, are unfit to rule our lives. But no one is fit to be our ruler. We deserve technological self-determination, not a corporatized internet made up of five giant services each filled with screenshots from the other four.

Cory Doctorow

Doctorow suggests breaking up these companies to end their de facto monopolies and level the playing field.

The problem of tech monopolies is something that Stowe Boyd explored in a recent article entitled Are Platforms Commons? Citing previous precedents around railroads, Boyd has many questions, including whether successful platforms be bound with the legal principles of 'common carriers', and finishes with this:

However, just one more question for today: what if ecosystems were constructed so that they were governed by the participants, rather by the hypercapitalist strivings of the platform owners — such as Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook — or the heavy-handed regulators? Is there a middle ground where the needs of the end user and those building, marketing, and shipping products and services can be balanced, and a fair share of the profits are distributed not just through common carrier laws but by the shared economics of a commons, and where the platform orchestrator gets a fair share, as well? We may need to shift our thinking from common carrier to commons carrier, in the near future.

Stowe Boyd

The trouble is, simply establishing a commons doesn't solve all of the problems. In fact, what tends to happen next is well known:

The tragedy of the commons is a situation in a shared-resource system where individual users, acting independently according to their own self-interest, behave contrary to the common good of all users, by depleting or spoiling that resource through their collective action.

Wikipedia

An article in The Economist outlines the usual remedies to the 'tragedy of the commons': either governmental regulation (e.g. airspace), or property rights (e.g. land). However, the article cites the work of Elinor Ostrom, a Nobel prizewinning economist, showing that another way is possible:

An exclusive focus on states and markets as ways to control the use of commons neglects a varied menagerie of institutions throughout history. The information age provides modern examples, for example Wikipedia, a free, user-edited encyclopedia. The digital age would not have dawned without the private rewards that flowed to successful entrepreneurs. But vast swathes of the web that might function well as commons have been left in the hands of rich, relatively unaccountable tech firms.

[...]

A world rich in healthy commons would of necessity be one full of distributed, overlapping institutions of community governance. Cultivating these would be less politically rewarding than privatisation, which allows governments to trade responsibility for cash. But empowering commoners could mend rents in the civic fabric and alleviate frustration with out-of-touch elites.

The Economist

I count myself as someone on the left of politics, if that's how we're measuring things today. However, I don't think we need representation at any higher level than is strictly necessary.

In a time when technology allows you, to a great extent, to represent yourself, perhaps we need ways of demonstrating how complex and multi-faceted some issues are? Perhaps we need to try 'liquid democracy':

Liquid democracy lies between direct and representative democracy. In direct democracy, participants must vote personally on all issues, while in representative democracy participants vote for representatives once in certain election cycles. Meanwhile, liquid democracy does not depend on representatives but rather on a weighted and transitory delegation of votes. Liquid democracy through elections can empower individuals to become sole interpreters of the interests of the nation. It allows for citizens to vote directly on policy issues, delegate their votes on one or multiple policy areas to delegates of their choosing, delegate votes to one or more people, delegated to them as a weighted voter, or get rid of their votes' delegations whenever they please.

WIkipedia

I think, given the state that politics is in right now, it's well worth a try. The problem, of course, is that the losers would be the political elites, the current incumbents. But, hey, it's not a revolution if nobody loses, right?

Saturday strikings

This week's roundup is going out a day later than usual, as yesterday was the Global Climate Strike and Thought Shrapnel was striking too!

Here's what I've been paying attention to this week:

Neoliberalism in any guise is not the solution but the problem

Today's quotation-as-title is from Nancy Fraser, whose short book The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born in turn gets its title from a quotation from Antonio Gramsci.

It's an excellent book; quick to read, straight to the point, and it helped me to understand some of what is going on at the moment in both US and world politics.

First, let's explain terms, as it is a book that presupposes some knowledge of political philosophy. 'Neoliberalism' isn't an easy term to define, as its meaning has mutated over time, and it's usually used in a derogatory way.

There's a whole history of the term at Wikipedia, but I'll use definitions from Investopedia and The Guardian:

Neoliberalism is a policy model—bridging politics, social studies, and economics—that seeks to transfer control of economic factors to the private sector from the public sector. It tends towards free-market capitalism and away from government spending, regulation, and public ownership.

Investopedia

In short, “neoliberalism” is not simply a name for pro-market policies, or for the compromises with finance capitalism made by failing social democratic parties. It is a name for a premise that, quietly, has come to regulate all we practise and believe: that competition is the only legitimate organising principle for human activity.

Guardian

To me, it's the reason why humans go out of their way to engineer situations where people and organisations are pitted against each other to compete for 'awards', no matter how made-up or paid-for they may be. It's a way of framing society, human interactions, and reducing everything to $$$.

In that vein, the most recent issue of New Philosopher, features an essay by Warwick Smith where he uses the thought experiment of an AI 'paperclip maximiser'. This runs amok and turns the entire universe into paperclips:

I recently heard Daniel Schmachtenberger taking this thought experiment in a very interesting direction by saying that human society is already the paperclip maximiser but instead of making paperclips we're making dollars — which are primarily just zeroes and ones in bank databases. Our collective intelligence system has on overriding purpose: to turn everything into money — trees, labour, water... everything. It is also very good at learning how to learn and is extremely good at eliminating any threats.

Warwick Smith

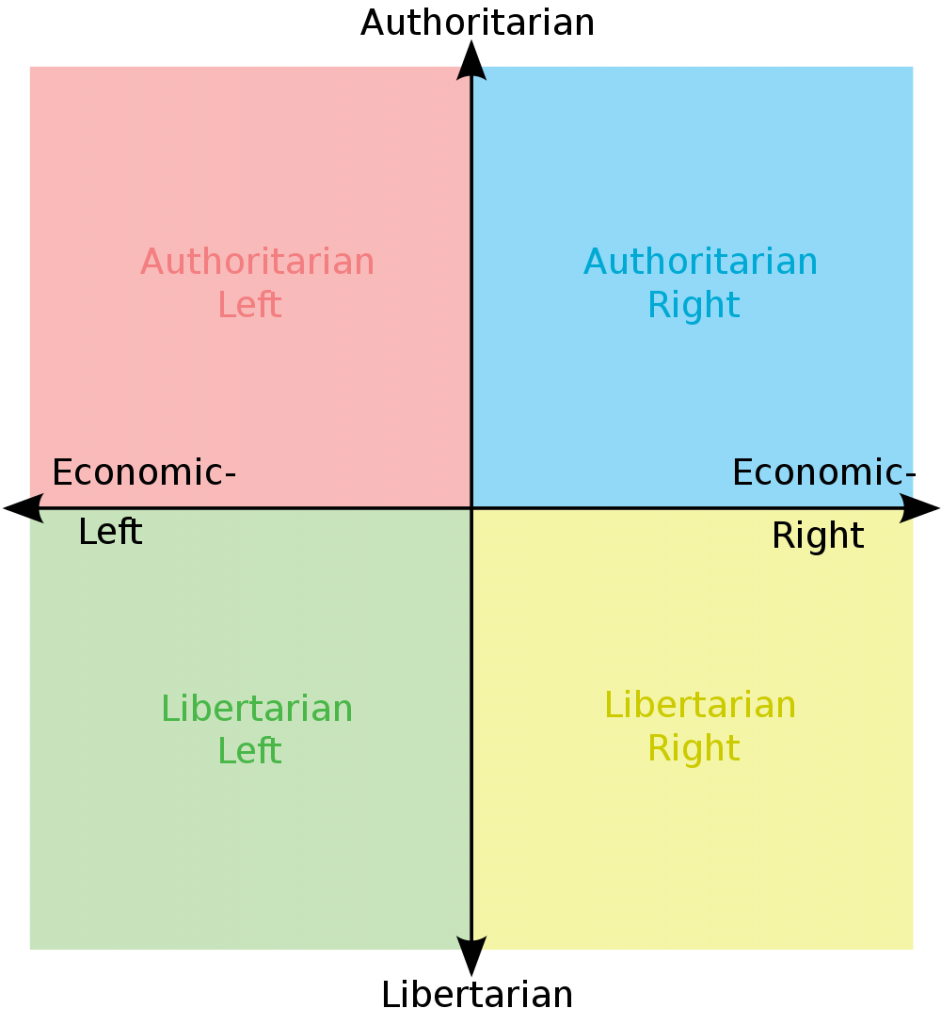

This attempt to turn everything into money is basically the neoliberal project. What Nancy Fraser does is identify two different strains of neoliberalism, which she explains through the lenses of 'distribution' and 'recognition':

The difference between these two strands of neoliberalism, then, comes in the way that they recognise people. Note that the method of distribution remains the same:

The political universe that Trump upended was highly restrictive. It was built around the opposition between two versions of neoliberalism, distinguished chiefly on an axis of recognition. Granted, one could choose between multiculturalism and ethnonationalism. But one was stuck, either way, with financialization and deindustrialization. With the menu limited to progressive and reactionary neoliberalism, there was no force to oppose the decimation of working-class and middle-class standards of living. Antineoliberal projects were severely marginalized, if not simply excluded from the public sphere.

Nancy Fraser

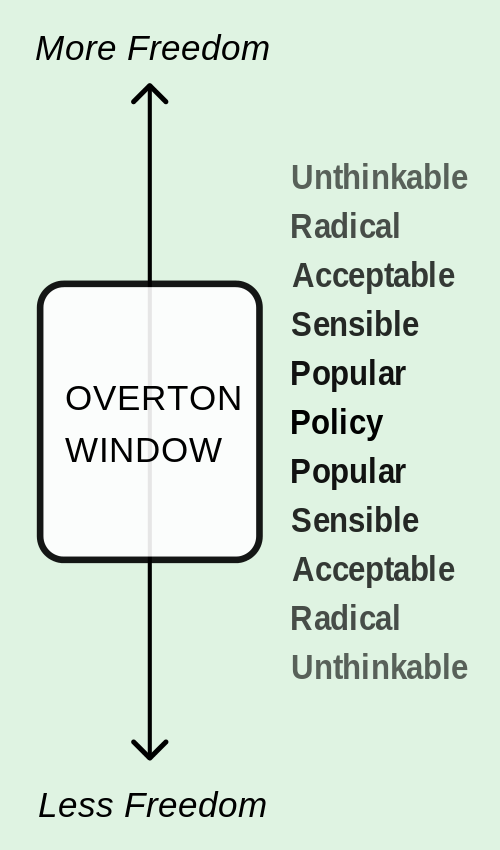

It's as if the Overton Window of acceptable public political discourse served up a menu of only different flavours of neoliberalism:

Ideologies are oriented within a narrative that spans the past, present, and future. We can argue over visions of what education should look like within a society, for example, because we're interested in how the next generation will turn out.

In Present Shock, Douglas Rushkoff explains that instead of shackling themselves to ideologies, Trump and other populist politicians take advantage of the 24/7 'always on' media landscape to provide a constant knee-jerk presentism:

A presentist mediascape may prevent the construction of false and misleading narratives by elites who mean us no good, but it also tends to leave everyone looking for direction and responding or overresponding to every bump in the road.

Douglas Rushkoff

What we're witnessing is essentially the end of politics as we know it, says Rushkoff:

As a result, what used to be called statecraft devolves into a constant struggle with crisis management. Leaders cannot get on top of issues, much less ahead of them, as they instead seek merely to respond to the emerging chaos in a way that makes them look authoritative.

[...]

If we have no destination toward we are progressing, then the only thing that motivates our movement is to get away from something threatening. We move from problem to problem, avoiding calamity as best we can, our worldview increasingly characterized by a sense of panic.

[...]

Blatant shock is the only surefire strategy for gaining viewers in the now.

Douglas Rushkoff

We might be witnessing the end of progressive neoliberalism, but it's not as if that's being replaced by anything different, anything better.

What, then, can we expect in the near term? Absent a secure hegemony, we face an unstable interregnum and the continuation of the political crisis. In this situation, the words of Gramsci ring true: "The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear."

Nancy Fraser

No matter what the question is, neoliberalism is never the answer. The trouble, I think, is that two-dimensional diagrams of political options are far too simplistic:

For example, as Edurne Scott Loinaz shows, even within the Libertarian Left (the 'lower left') there are many different positions:

The Libertarian Left has perhaps the best to offer in terms of fighting neoliberalism and populists like Trump. The problem is unity, and use of language:

When binary language is used within the lower left it does untold violence to our communities and makes solidarity impossible: if one can switch between binary language to speak truth about capitalists and authoritarians, and switch to dimensional language within the zone of solidarity with fellow lower leftists, it will be easier to nurture solidarity within the lower left.

Edurne Scott Loinaz

For the first time in my life, I'm actually somewhat fearful of what comes next, politically speaking. Are we going to end up with populists entrenching the authoritarian right, going back full circle to reactionary neoliberalism? Or does this current crisis mean that something new can emerge?

Header image by Guillaume Paumier used under a Creative Commons license

Let's not force children to define their future selves through the lens of 'work'

I discovered the work of Adam Grant through Jocelyn K. Glei's excellent Hurry Slowly podcast. He has his own, equally excellent podcast, called WorkLife which he creates with the assistance of TED.

Writing in The New York Times as a workplace psychologist, Grant notes just how problematic the question "what do you want to be when you grow up?" actually is:

When I was a kid, I dreaded the question. I never had a good answer. Adults always seemed terribly disappointed that I wasn’t dreaming of becoming something grand or heroic, like a filmmaker or an astronaut.

Let's think: from what I can remember, I wanted to be a journalist, and then an RAF pilot. Am I unhappy that I'm neither of these things? No.

Perhaps it's because a job is more tangible than an attitude or approach to life, but not once can I remember being asked what kind of person I wanted to be. It was always "what do you want to be when you grow up?", and the insinuation was that the answer was job-related.

My first beef with the question is that it forces kids to define themselves in terms of work. When you’re asked what you want to be when you grow up, it’s not socially acceptable to say, “A father,” or, “A mother,” let alone, “A person of integrity.”

[...]

The second problem is the implication that there is one calling out there for everyone. Although having a calling can be a source of joy, research shows that searching for one leaves students feeling lost and confused.

Another fantastic podcast episode I listened to recently was Tim Ferriss' interview of Caterina Fake. She's had an immensely successful career, yet her key messages during that conversation were around embracing your 'shadow' (i.e. melancholy, etc.) and ensuring that you have a rich inner life.

While the question beloved of grandparents around the world seems innocuous enough, these things have material effects on people's lives. Children are eager to please, and internalise other people's expectations.

I’m all for encouraging youngsters to aim high and dream big. But take it from someone who studies work for a living: those aspirations should be bigger than work. Asking kids what they want to be leads them to claim a career identity they might never want to earn. Instead, invite them to think about what kind of person they want to be — and about all the different things they might want to do.

The jobs I've had over the last decade didn't really exist when I was a child, so it would have been impossible to point to them. Let's encourage children to think of the ways they can think and act to change the world for the better - not how they're going to pay the bills to enable themselves to do so.

Source: The New York Times

Also check out:

What did the web used to be like?

One of the things it’s easy to forget when you’ve been online for the last 20-plus years is that not everyone is in the same boat. Not only are there adults who never experienced the last millennium, but varying internet adoption rates mean that, for some people, centralised services like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are synonymous with the web.

Stories are important. That’s why I appreciated this Hacker News thread with the perfect title and sub-title:

Ask HN: What was the Internet like before corporations got their hands on it? What was the Internet like in its purest form? Was it mainly information sharing, and if so, how reliable was the information?There's lots to unpack here: corporate takeover of online spaces, veracity of information provided, and what the 'purest form' of the internet actually is/was.

Inevitably, given the readership of Hacker News, the top-voted post is technical (and slightly boastful):

1990. Not very many people had even heard of it. Some of us who'd gotten tired of wardialing and Telenet/Tymnet might have had friends in local universities who clued us in with our first hacked accounts, usually accessed by first dialing into university DECServers or X.25 networks. Overseas links from NSFNet could be as slow as 128kbit and you were encouraged to curtail your anonymous FTP use accordingly. Yes you could chat and play MUDs, but you could also hack so many different things. And admins were often relatively cool as long as you didn't use their machines as staging points to hack more things. If you got your hands on an outdial modem or x.25 gateway, you were sitting pretty sweet (until someone examined the bill and kicked you out). It really helped to be conversant in not just Unix, but also VMS, IBM VM/CMS, and maybe even Primenet. When Phrack came out, you immediately read it and removed it from your mail spool, not just because it was enormous, but because admins would see it and label you a troublemaker.I’ve already detailed my early computing history (up to 2009) for a project that asked for my input. I’ll not rehash it here, but the summary is that I got my first PC when I was 15 for Christmas 1995, and (because my parents wouldn’t let me) secretly started going online soon after.We knew what the future was, but it was largely a secret. We learned Unix from library books and honed skills on hacked accounts, without any ethical issue because we honestly felt we were preparing ourselves and others for a future where this kind of thing should be available to everyone.

We just didn’t foresee it being wirelessly available at McDonalds, for free. That part still surprises me.

My memory of this from an information-sharing point of view was that you had to be very careful about what you read. Because the web was smaller, and it was only the people who were really interested in getting their stuff out there who had websites, there was a lot of crazy conspiracy theories. I’m kind of glad that I went on as a reasonably-mature teenager rather than a tween.

Although I’ve very happy to be able to make my living primarily online, I suppose I feel a bit like this commenter:

This will probably come across as Get Of My Lawn type of comment. What I remember most about internet pre Facebook in particular and maybe Pre-smart phones. It was mostly a place for geeks. Geeks wrote blogs or had personal websites. Non geek stuff was more limited. It felt like a place where the geeks that were semi socially outcast kind of ran the place.Another commenter pointed to a short blog post he wrote on the subject, where he talks about how things were better when everyone was anonymous:Today the internet feels like the real world where the popular people in the real world are the most popular people online. Where all the things that I felt like I escaped from on the net before I can no longer avoid.

I’m not saying that’s bad. I think it’s awesome that my non tech friends and family can connect and or share their lives and thoughts easily where as before there was a barrier to entry. I’m only pointing out that, at least for me, it changed. It was a place I liked or felt connected to or something, maybe like I was “in the know” or I can’t put my finger on it. To now where I have no such feelings.

Maybe it’s the same feeling as liking something before it’s popular and it loses that feeling of specialness once everyone else is into it. (which is probably a bad feeling to begin with)

When it was anonymous, your name wasn’t attached to everything you did online. Everyone went by a handle. This means you could start a Geocities site and carve out your own niche space online, people could befriend and follow you who normally wouldn’t, and even the strangest of us found a home. All sorts of whacky, impossible things were possible because we weren’t bound by societal norms that plague our daily existence.I get that, but I think that things that make sense and are sustainable for the few, aren't necessarily so for the many. There's nothing wrong with nostalgia and telling stories about how things used to be, but as someone who used to teach the American West, there is (for better or worse) a parallel there with the evolution of the web.

The closest place to how the web was that I currently experience is Mastodon. It’s fully of geeks, marginalised groups, and weird/wacky ideas. You’d love it.

Source: Hacker News

Old web screenshot compilation image via Vice

The problem with Business schools

This article is from April 2018, but was brought to my attention via Harold Jarche’s excellent end-of-year roundup.

Business schools have huge influence, yet they are also widely regarded to be intellectually fraudulent places, fostering a culture of short-termism and greed. (There is a whole genre of jokes about what MBA – Master of Business Administration – really stands for: “Mediocre But Arrogant”, “Management by Accident”, “More Bad Advice”, “Master Bullshit Artist” and so on.) Critics of business schools come in many shapes and sizes: employers complain that graduates lack practical skills, conservative voices scorn the arriviste MBA, Europeans moan about Americanisation, radicals wail about the concentration of power in the hands of the running dogs of capital. Since 2008, many commentators have also suggested that business schools were complicit in producing the crash.When I finished my Ed.D. my Dad jokingly (but not-jokingly) said that I should next aim for an MBA. At the time, eight years ago, I didn't have the words to explain why I had no desire to do so. Now however, understanding a little bit more about economics, and a lot more about co-operatives, I can see that the default operating system of organisations is fundamentally flawed.

If we educate our graduates in the inevitability of tooth-and-claw capitalism, it is hardly surprising that we end up with justifications for massive salary payments to people who take huge risks with other people’s money. If we teach that there is nothing else below the bottom line, then ideas about sustainability, diversity, responsibility and so on become mere decoration. The message that management research and teaching often provides is that capitalism is inevitable, and that the financial and legal techniques for running capitalism are a form of science. This combination of ideology and technocracy is what has made the business school into such an effective, and dangerous, institution.I'm pretty sure that forming a co-op isn't on the curriculum of 99% of business schools. As Martin Parker, the author of this long article points out, after teaching in 'B-schools' for 20 years, ethical practices are covered almost reluctantly.

The problem is that business ethics and corporate social responsibility are subjects used as window dressing in the marketing of the business school, and as a fig leaf to cover the conscience of B-school deans – as if talking about ethics and responsibility were the same as doing something about it. They almost never systematically address the simple idea that since current social and economic relations produce the problems that ethics and corporate social responsibility courses treat as subjects to be studied, it is those social and economic relations that need to be changed.So my advice to someone who's thinking of doing an MBA? Don't bother. You're not going to be learning things that make the world a better place. Save your money and do something more worthwhile. If you want to study something useful, try researching different ways of structuring organistions — perhaps starting by using this page as a portal to a Wikipedia rabbithole?

Source: The Guardian (via Harold Jarche)

The endless Black Friday of the soul

This article by Ruth Whippman appears in the New York Times, so focuses on the US, but the main thrust is applicable on a global scale:

Apparently, 94% of the jobs created in the last decade are freelancer or contract positions. That's the trajectory we're on.When we think “gig economy,” we tend to picture an Uber driver or a TaskRabbit tasker rather than a lawyer or a doctor, but in reality, this scrappy economic model — grubbing around for work, all big dreams and bad health insurance — will soon catch up with the bulk of America’s middle class.

I don't think this is a neoliberal conspiracy, it's just the logic of capitalism seeping into every area of society. As we all jockey for position in the new-ish landscape of social media, everything becomes mediated by the market.Almost everyone I know now has some kind of hustle, whether job, hobby, or side or vanity project. Share my blog post, buy my book, click on my link, follow me on Instagram, visit my Etsy shop, donate to my Kickstarter, crowdfund my heart surgery. It’s as though we are all working in Walmart on an endless Black Friday of the soul.

[...]

Kudos to whichever neoliberal masterminds came up with this system. They sell this infinitely seductive torture to us as “flexible working” or “being the C.E.O. of You!” and we jump at it, salivating, because on its best days, the freelance life really can be all of that.

What I think’s missing from this piece, though, is a longer-term trend towards working less. We seem to be endlessly concerned about how the nature of work is changing rather than the huge opportunities for us to do more than waste away in bullshit jobs.

I’ve been advising anyone who’ll listen over the last few years that reducing the number of days you work has a greater impact on your happiness than earning more money. Once you reach a reasonable salary, there’s diminishing returns in any case.

Source: The New York Times (via Dense Discovery)

Is UBI 'hush money'?

Over the last few years, I’ve been quietly optimistic about Universal Basic Income, or ‘UBI’. It’s an approach that seems to have broad support across the political spectrum, although obviously for different reasons.

A basic income, also called basic income guarantee, universal basic income (UBI), basic living stipend (BLS), or universal demogrant, is a type of program in which citizens (or permanent residents) of a country may receive a regular sum of money from a source such as the government. A pure or unconditional basic income has no means test, but unlike Social Security in the United States it is distributed automatically to all citizens without a requirement to notify changes in the citizen's financial status. Basic income can be implemented nationally, regionally or locally. (Wikipedia)Someone who's thinking I hugely respect, Douglas Rushkoff, thinks that UBI is a 'scam':

The policy was once thought of as a way of taking extreme poverty off the table. In this new incarnation, however, it merely serves as a way to keep the wealthiest people (and their loyal vassals, the software developers) entrenched at the very top of the economic operating system. Because of course, the cash doled out to citizens by the government will inevitably flow to them.I have to agree with Rushkoff when he talks about UBI leading to more passivity and consumption rather than action and ownership:Think of it: The government prints more money or perhaps — god forbid — it taxes some corporate profits, then it showers the cash down on the people so they can continue to spend. As a result, more and more capital accumulates at the top. And with that capital comes more power to dictate the terms governing human existence.

Rushkoff calls UBI 'hush money', a method for keeping the masses quiet while those at the top become ever more wealthy. Unfortunately, we live in the world of the purist, where no action is good enough or pure enough in its intent. I agree with Rushkoff that we need more worker ownership of organisations, but I appreciate Noam Chomsky's view of change: you don't ignore an incremental improvement in people's lives, just because you're hoping for a much bigger one round the corner.Meanwhile, UBI also obviates the need for people to consider true alternatives to living lives as passive consumers. Solutions like platform cooperatives, alternative currencies, favor banks, or employee-owned businesses, which actually threaten the status quo under which extractive monopolies have thrived, will seem unnecessary. Why bother signing up for the revolution if our bellies are full? Or just full enough?

Under the guise of compassion, UBI really just turns us from stakeholders or even citizens to mere consumers. Once the ability to create or exchange value is stripped from us, all we can do with every consumptive act is deliver more power to people who can finally, without any exaggeration, be called our corporate overlords.

Source: Douglas Rushkoff

Is UBI 'hush money'?

Over the last few years, I’ve been quietly optimistic about Universal Basic Income, or ‘UBI’. It’s an approach that seems to have broad support across the political spectrum, although obviously for different reasons.

A basic income, also called basic income guarantee, universal basic income (UBI), basic living stipend (BLS), or universal demogrant, is a type of program in which citizens (or permanent residents) of a country may receive a regular sum of money from a source such as the government. A pure or unconditional basic income has no means test, but unlike Social Security in the United States it is distributed automatically to all citizens without a requirement to notify changes in the citizen's financial status. Basic income can be implemented nationally, regionally or locally. (Wikipedia)Someone who's thinking I hugely respect, Douglas Rushkoff, thinks that UBI is a 'scam':

The policy was once thought of as a way of taking extreme poverty off the table. In this new incarnation, however, it merely serves as a way to keep the wealthiest people (and their loyal vassals, the software developers) entrenched at the very top of the economic operating system. Because of course, the cash doled out to citizens by the government will inevitably flow to them.I have to agree with Rushkoff when he talks about UBI leading to more passivity and consumption rather than action and ownership:Think of it: The government prints more money or perhaps — god forbid — it taxes some corporate profits, then it showers the cash down on the people so they can continue to spend. As a result, more and more capital accumulates at the top. And with that capital comes more power to dictate the terms governing human existence.

Rushkoff calls UBI 'hush money', a method for keeping the masses quiet while those at the top become ever more wealthy. Unfortunately, we live in the world of the purist, where no action is good enough or pure enough in its intent. I agree with Rushkoff that we need more worker ownership of organisations, but I appreciate Noam Chomsky's view of change: you don't ignore an incremental improvement in people's lives, just because you're hoping for a much bigger one round the corner.Meanwhile, UBI also obviates the need for people to consider true alternatives to living lives as passive consumers. Solutions like platform cooperatives, alternative currencies, favor banks, or employee-owned businesses, which actually threaten the status quo under which extractive monopolies have thrived, will seem unnecessary. Why bother signing up for the revolution if our bellies are full? Or just full enough?

Under the guise of compassion, UBI really just turns us from stakeholders or even citizens to mere consumers. Once the ability to create or exchange value is stripped from us, all we can do with every consumptive act is deliver more power to people who can finally, without any exaggeration, be called our corporate overlords.

Source: Douglas Rushkoff

Reappropriating the artifacts of late-stage capitalism

During our inter-railing adventure this summer, we visited Zurich in Switzerland. In one of the parks there, we came across a dockless scooter, which we promptly unlocked and had a great time zooming around.

As you’d expect, the greatest density of dockless bikes and scooters — devices that don’t have to be picked up or returned in any specific place — is in San Francisco. It seems that, in their attempts to flood the city and gain some kind of competitive advantage, VC-backed dockless bike and scooter startups are having an unintended effect. They’re helping homeless people move around the city more easily:

Hoarding and vandalism aren't the only problems for electric scooter companies. There's also theft. While the vehicles have GPS tracking, once the battery fully dies they go off the app's map.Source: CNET (via BoingBoing)“Every homeless person has like three scooters now,” [Michael Ghadieh, who owns electric bicycle shop, SF Wheels] said. “They take the brains out, the logos off and they literally hotwire it.”

I’ve seen scooters stashed at tent cities around San Francisco. Photos of people extracting the batteries have been posted on Twitter and Reddit. Rumor has it the batteries have a resale price of about $50 on the street, but there doesn’t appear to be a huge market for them on eBay or Craigslist, according to my quick survey.

Capitalism can make you obese

From a shocking photojournalism story:

With imported soft drinks costing the same or less than bottled water, in a country where tap water is not safe to drink, the poorest people are most likely to develop diabetes. Mexico’s health ministry said in 2016 that 72% of adults were overweight or obese. But the same people are prone to malnutrition thanks to a diet high in sugar and saturated fats and low in fibreSource: The Guardian