Yuval Noah Harari on the post-truth revolutionary right

Friend and collaborator Bryan Mathers recommended this episode of The Rest is Politics: Leading to me. While I’m a regular listener to the main podcast, which features only Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart, I hadn’t previously bothered with the ones where they interview others.

This one with Yuval Noah Harari is great. It’s the second part of a two-part interview. In the first, recorded in August, Harari talks about the situation in Israel. In this second one, he zooms out a bit to talk about politics more generally, AI, and society.

The thing that struck me, about 5-10 minutes in, was his point about the left and right of politics not making sense any more. That’s something that others have said before. But his analysis was fascinating: the right has largely abandoned the role of being guardians of tradition to weaponise ‘truth’, which has led to the left being in the awkward position of custodian. That’s why everything feels topsy-turvy.

(also, I’m really pleased to have discovered pod.link to share podcast episodes in a non-platform-specific way as easily as song.link)

(also also, I found out about a podcast search engine call Listen Notes recently!)

Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell, hosts of Britain's biggest podcast (The Rest Is Politics), have joined forces once again for their new interview podcast, ‘Leading’.Every Monday, Rory and Alastair interrogate, converse with, and interview some of the world's biggest names - from both inside and outside of politics - about life, leadership, or leading the way in their chosen field.Whether they're sports stars, thought-leaders, presidents or internationally-recognised religious figures, Alastair and Rory lift the lid on the motivation, philosophy and secrets behind their career.Tune in to 'Leading' now to hear essential conversation from some of the world's most enthralling individuals.Source: The Rest is Politics: Leading

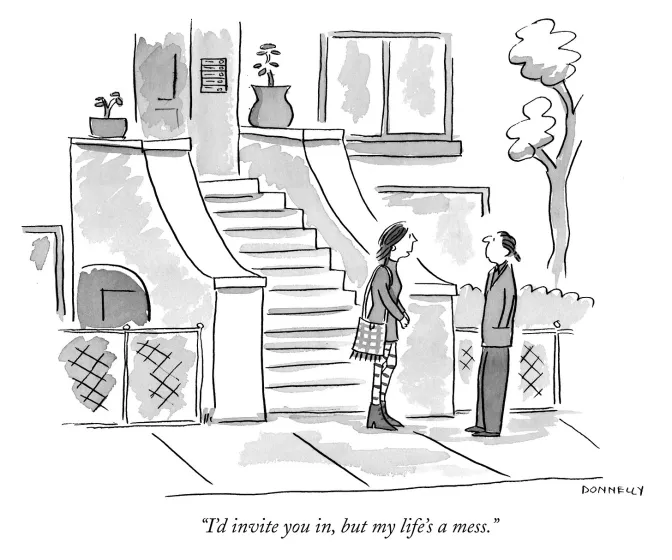

Telling stories using cartoons

Liza Donnelly is a cartoonist for the New Yorker. In this article, which is an output from some preparatory work for a talk she’s preparing, she talks about how the best cartoons work.

I’ve had the privilege of working with Bryan Mathers over the last decade and it really is a fascinating process. In fact, he’s just delivered a bunch of artwork for the work we’re doing around Open Recognition. Check it out here!

Story is everywhere. In single panel cartoons, they have to be kept in one image. It’s tricky and challenging and I love it. I like to say that a single panel cartoon is like a mini stage. The artist is a set designer, choreographer, script writer, costume designer, casting director. Each element in the drawing needs to be necessary for the idea, no more, no less; there are exceptions of course. Some creators are known for a style that is overly detailed and complicated, and that is part of the voice of the artist and contributes to the story. The image is a moment in time, and you have to feel that there is time before the moment you see, and a continuation after that moment. And the characters are well “described” in the execution.Source: Storytelling In Drawing | Seeing Things[…]

Bottom line: story in the best New Yorker cartoons tell us a story about the characters that are in the drawing, and about ourselves. This is why we love them so much—they are fun, entertaining and are about us.

Conspicuously sesquipedalian communication

Getting people to understand your ideas is a difficult thing. That’s why it’s been so gratifying to work at various times with Bryan Mathers over the last decade. We humans are much better at processing visual inputs than deciphering text.

That being said, as Derek Thompson shows in this article, you have to begin with the realisation that simple is smart. It’s much easier to just write down what’s in your head that do so in a way that’s easy for others to understand.

In some ways, this reminds me of my work on ambiguity, which was a side-product of the work I did on my doctoral thesis. It’s also a good reminder that one of the best uses that most people can make of AI tools such as ChatGPT is to simplify their work.

High school taught me big words. College rewarded me for using big words. Then I graduated and realized that intelligent readers outside the classroom don’t want big words. They want complex ideas made simple. If you don’t believe it from a journalist, believe it from an academic: “When people feel insecure about their social standing in a group, they are more likely to use jargon in an attempt to be admired and respected,” the Columbia University psychologist Adam Galinsky told me. His study and other research found that when people use complicated language, they tend to come across as low-status or less intelligent. Why? It’s the complexity trap: Complicated language and jargon offer writers the illusion of sophistication, but jargon can send a signal to some readers that the writer is dense or overcompensating. Conspicuously sesquipedalian communication can signal compensatory behavior resulting from suboptimal perspective-taking strategies. What? Exactly; never write like that. Smart people respect simple language not because simple words are easy, but because expressing interesting ideas in small words takes a lot of work.Source: Why Simple Is Smart | The Atlantic

Optimise for energy and motivation

While this post has a clickbait-y subtitle (‘Why I quit a $500K job at Amazon to work for myself’) it nevertheless makes an important point:

Last week I left my cushy job at Amazon after 8 years. Despite getting rewarded repeatedly with promotions, compensation, recognition, and praise, I wasn’t motivated enough to do another year.As author Daniel Pink points out in his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, when it comes down to it, neither money nor people saying "good job" is why we go to work. We want to do stuff that's meaningful.

What kind of work would I do if I had to do it forever? Not something that I did until I reached some milestone (an exit), but something that I would consider satisfactory if I continued to do it until I’m 80. What is out there that I could do that would make me excited waking up every day for the next 45 years that could also earn me enough money to cover my expenses? Is that too unambitious? I don’t think so.I'm nowhere near this guy's earnings, but I do earn about twice as much as I did as a senior leader in schools. That would have been a ridiculous amount of money to me a few years ago, but you get used to it. The point is that you have to be doing something sustainable.

The things that don’t wear off are those that I’ve been doing since I was a kid, when nothing was forcing me to do them. Things such as writing code, selling my creations, charting my own path, calling it like I saw it. I know my strengths, and I know what motivates me, so why not do this all the time? I’m lucky to live in a time where I can do something independently in my area of expertise without requiring large amounts of capital or outside investors. So that’s what I’m doing.A couple of weeks ago I volunteered to be an Assistant Scout Leader. I realised how much I missed interacting with kids of that age (over and above my own, of course) but teaching isn't the only way of going about doing that.

The interesting thing is that, if you do something you find interesting, something that gets you out of bed in the morning, the money will come at some point. I’m not naive enough to think that “follow your dreams” is good career advice, but you certainly shouldn’t be doing something you hate. Not long-term, anyway.

On that note, it’s been a delight to see how Bryan Mathers is pulling together his artistic chops (which he’s honed from zero this decade) and his coding skills to create The Remixer Machine. It seemed to come from nowhere but, of course, it’s taken skills and interests that he’s combined to make something worthwhile in the world.

So, what can you do practically if you’re reading this? Optimise for energy and motivation. In practice, that means do something that you love at a time you’ve got most energy. If you’re a morning person, do something that inspires you before work. If you’re super-motivated around lunchtime, do something in your lunch break. Night owl? You know what to do…

Source: Daniel Vassallo