2024

A typology of meme-sharing

I don’t know about you, but responding to a family member, friend, or professional contact using a meme has been a daily event for a long time now. It’s now over 12 years since I gave my meme-laden talk at TEDx Warwick based on my doctoral thesis. A year later, I gave a presentation (in the midst of growing a beard for charity) which used nothing but gifs. But I digress.

This article from New Public gives a typology of meme-sharing, which is useful. One of the things I wish I had realised, because looking back with hindsight it’s so obvious, is the way that memes can be weaponised to create in-groups and out-groups, and to perpetuate hate. Not that I could have done much about it.

There are at least three types of connections that can be forged through meme-sharing: bonding over a shared interest such as movies, sports, and more; bonding over an experience or circumstance; or bonding over a feeling or personal sentiment.

[…]

Sharing memes to connect over common interests is perhaps the most surface-level form of meme-sharing. It hinges exclusively on having shared cultural references rather than shared personal commonalities. These exchanges are more likely to occur in established relationships, such as among family and friends that have shared lived experiences and therefore are exposed to the same cultural references and social cues.

[…]

Connecting over a shared interest can be like connecting over a single data point. But people are so much more complicated. That is why connecting over experiences, which are often inherently more rich and embedded with memories and emotion, can yield a more powerful connection.

[…]

Connecting over shared feelings can be even more moving. There is something particularly intimate about connecting over emotions, and at the same time, universal. As humans, we are rarely self-aware of all of our internal thoughts and feelings, so a meme that can connect with them unexpectedly, like the one below (sound on!), can be powerful.

[…]

These three ways of forming connection through meme-sharing are of course not mutually exclusive, and they are far from being collectively exhaustive. There are definitely instances of meme-sharing which accomplish all of these…

And there can also be situations in which people share memes for reasons outside of connecting over identity, experience, or feelings. Rather, what this typology illustrates is the ways that we can (and do!) cultivate belonging with others online through the sharing of comedic imagery.

Source: New Public

Image: Know Your Meme

Fediverse governance models

Erin Kissane and Darius Kazemi have published a report on Fediverse governance which is the kind of thing I would have read with relish when I was Product Manager of MoodleNet. And even before then when I was presenting on decentralisation and censorship in the midst of the ‘illegal’ Catalan independence referendum.

These days, while still interested in this kind of stuff, and in particular in [how misinformation might be countered in decentralised networks]9bonfirenetworks.org/posts/zap…) I’m not going to be reading 40,000 words on the subject (PDF). Instead point others to it, and in particular to six-page ‘quick start’ guide for those who might be new to the idea of federated governance.

I wouldn’t have guessed, going in, that we’d end up with the major structural categories we landed on—moderation, server leadership, and federated diplomacy—but after spending so much time eyeball-deep in interview transcripts, I think it’s a pretty reasonable structure for discussing the big picture of governance. (The real gold is of course in the excerpts and summaries from our participants, who continuously challenged and surprised us.)

There are no manifestos to be found here, except in that our participants often eloquently and sometimes passionately express their hopes for the fediverse. There are a lot of assumptions, most of which we’ve tried to be pretty scrupulous about calling out in the text, but anything this chunky contains plentiful grist for both principled disagreement and the other kind. Our aim is to describe and convey the knowledge inherent in fediverse server teams, so we’ve really stuck close to the kinds of problems, risks, needs, and challenges those folks expressed.

Source: Erin Kissane

Image: Google Deepmind

Life-ready signals

To be a professional, a knowledge worker in the 21st century, means keeping up with jargon, acronyms, and shifts in terminology. Some of this is necessary, as I’ve explained in my work on ambiguity, some isn’t.

This article by Kristine Chompff on the Edalex blog introduces a term new to me: “life-ready signals”. It doesn’t seem to me destined to catch-on, any more than ‘durable skills’ has or will, but is nevertheless a worthy attempt to recognise the behaviours that go around hard skills and knowledge.

I also think that we need to do something about the acronym soup: while I might understand someone saying that we use RSDs to build a VC as part of a learner’s PER within an LER ecosystem, it’s gobbledegook to everyone else.

For anyone interested in this kind of thing, we have a community of practice called Open Recognition is for Everybody (ORE) which you can discover and join at badges.community)

For us to understand life-ready signals, we must for a second talk about semiotics and the definition of terms. Because the term “life-ready skills” has evolved, so has the term “life-ready signals.”

Semiotics is the study of signs and symbols, of which language is a part. It depends partly on the object being described, but also on the way the person reading that description interprets it. For these terms to be meaningful, we all need to interpret them in the same way.

Life-ready skills are the thing being described. Life-ready signals are those “signs” being used to describe them. For a learner to tell their own story, they need to be equipped not only with the skills themselves, but the proper “signs” to share them with others in a meaningful way.

It’s also important to note here that with the rise of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) there will always be skills that machines will never master, and those are the life-ready skills we are discussing here.

Source: Edalex blog

Image: Giulia May

Begetting strangers

This is such a great article by Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker. Quoting philosophers, he concisely summarises the difficulty of parenting, examines some of the tensions, and settles on a position with which I’d agree.

It’s such a hard thing to do, especially with your first child, that I’m amazed there’s not some kind of mandatory classes. The hardest bit isn’t even the dealing with a new helpless infant, but the changes that kids go through on the road to adulthood. While we all went through them from the inside, trying to understand and help from the outside (while dealing with your own issues) is so difficult.

The fact that children are their own people can come as a surprise to parents. This is partly because young kids are so hopelessly dependent, but it also reflects how we think about parenthood… We talk as though having children is mainly “a matter of inclination, of personal desire, of appetite,” the philosopher Mara van der Lugt writes, in “Begetting: What Does It Mean to Create a Child?” She sees this as totally backward… Having children, van der Lugt argues, might be best seen as “a cosmic intervention, something great, and wondrous—and terrible.” We are deciding “that life is worth living on behalf of a person who cannot be consulted,” and we “must be prepared, at any point, to be held accountable for their creation.”

[…]

Van der Lugt is not pronatalist, but she isn’t anti-natalist, either. Her contention is simply that we should confront these questions more directly. Typically, she observes, it’s people who don’t want kids who are asked to explain themselves. Maybe it should work the other way, so that, when someone says that they want kids, people ask, “Why?”

[…]

In a 2014 book, “Family Values: The Ethics of Parent-Child Relationships,” the philosopher Harry Brighouse and the political theorist Adam Swift ask how we might relate to our children if we understand them, from the beginning of their lives, as independent individuals. There’s a tension, they write, between the ideals of a liberal society and the widely held “proprietarian view” of children: “The idea that children in some sense belong to their parents continues to influence many who reject the once-common view that wives belong to their husbands,” they note. But what’s the alternative? What would a family look like if the fundamental separateness of children was taken for granted, even during the years when they depend on us the most?

[…]

If the relationship between parents and children is based not on the proprietary “ownership” of kids by their parents but on the right of children to a certain kind of upbringing, then it makes sense to ask what parents must do to satisfy that right—and, conversely, what’s irrelevant to satisfying it. Brighouse and Swift, after pushing and prodding their ideas in various ways, conclude that their version of the family is a little less dynastic than usual. Some people, for instance, think that parents are entitled to do everything they can to give their children advantages in life. But, as the authors see it, some ways of seeking to advantage your children—from leaving them inheritances to paying for élite schooling—are not part of the bundle of “familial relationship goods” to which kids have a right; in fact, confusing these transactional acts for those goods—love, presence, moral tutelage, and so on—would be a mistake. This isn’t to say that parents mustn’t give their kids huge inheritances or send them to private schools. But it is to say that, if the government decides to raise the inheritance tax, it isn’t interfering with some sacred parental right.

[…]

“The basic point is simple,” they write. “Children are separate people, with their own lives to lead, and the right to make, and act on, their own judgments about how they are to live those lives. They are not the property of their parents.”

Source: The New Yorker

(use Archive Buttons if you can’t get access}

The thorny problem of authorship in a world of AI

This is an interesting article by Justine Tunney who argues that Open Source developers are having their contributions erased from history by LLMs. It’s interesting to consider this by field, as LLMs seem to have no problem explaining accurately what I’m known for (digital literacies, etc.)

As Tunney points out, the world of Open Source is a gift economy. But if we’re gifting things to something ingesting everything indiscriminately and then regurgitating in a way that erases authorship, is that problematic?

In a world of infinite automation and infinite surveillance, survival is going to depend on being the least boring person. Over my career I’ve written and attached my name to thousands of public source code files. I know they are being scraped from the web and used to train AIs. But if I ask something like Claude, “what sort of code has Justine Tunney wrote?” it hasn’t got the faintest idea. Instead it thinks I’m a political activist, since it feels no guilt remembering that I attended a protest on Wall Street 13 years ago. But all of the positive things I’ve contributed to society? Gifts I took risks and made great personal sacrifices to give? It’d be the same as if I sat my hands.

I suspect what happens is the people who train AI models treat open source authorship information as PII [Personally Identifiable Information]. When assembling their datasets, there are many programs you can find on GitHub for doing this, such as presidio which is a tool made by Microsoft to scrub knowledge of people from the data they collect. So when AIs are trained on my code, they don’t consider my git metadata, they don’t consider my copyright comments; they just want the wisdom and alpha my code contains, and not the story of the people who wrote it. When the World Wide Web was first introduced to the public in the 90’s, consumers primarily used it for porn, and while things have changed, the collective mindset and policymaking are still stuck in that era. Tech companies do such a great job protecting privacy that they’ll erase us from the book of life in the process.

Is this the future we want? Imagine if Isaac Newton’s name was erased, but the calculus textbooks remained. If we dehumanize knowledge in this manner, then we risk breaking one of the fundamental pillars that’s enabled science and technology to work in our society these last 500 years. I’ve yet to meet a scientist, aside from maybe Satoshi Nakamoto, who prefers to publish papers anonymously. I’m not sure if I would have gotten into coding when I was a child if I couldn’t have role models like Linus Torvalds to respect. He helped me get where I am today, breathing vibrant life into the digital form of a new kind of child. So if these AIs like Claude are learning from my code, then what I want is for Claude to know and remember that I helped it. This is actually required by the ISC license.

Source: justine’s web page

Image: Marcus Spiske

Government and algorithmic bias

If any government is going of, by, and for the people, then we can’t have unaccountable black box algorithms making important decisions. This is a welcome move.

Source: The Guardian

Artificial intelligence and algorithmic tools used by central government are to be published on a public register after warnings they can contain “entrenched” racism and bias.

Officials confirmed this weekend that tools challenged by campaigners over alleged secrecy and a risk of bias will be named shortly. The technology has been used for a range of purposes, from trying to detect sham marriages to rooting out fraud and error in benefit claims.

[…]

In August 2020, the Home Office agreed to stop using a computer algorithm to help sort visa applications after it was claimed it contained “entrenched racism and bias”. Officials suspended the algorithm after a legal challenge by the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants and the digital rights group Foxglove.

It was claimed by Foxglove that some nationalities were automatically given a “red” traffic-light risk score, and those people were more likely to be denied a visa. It said the process amounted to racial discrimination.

[…]

Departments are likely to face further calls to reveal more details on how their AI systems work and the measures taken to reduce the risk of bias. The DWP is using AI to detect potential fraud in advance claims for universal credit, and has more in development to detect fraud in other areas.

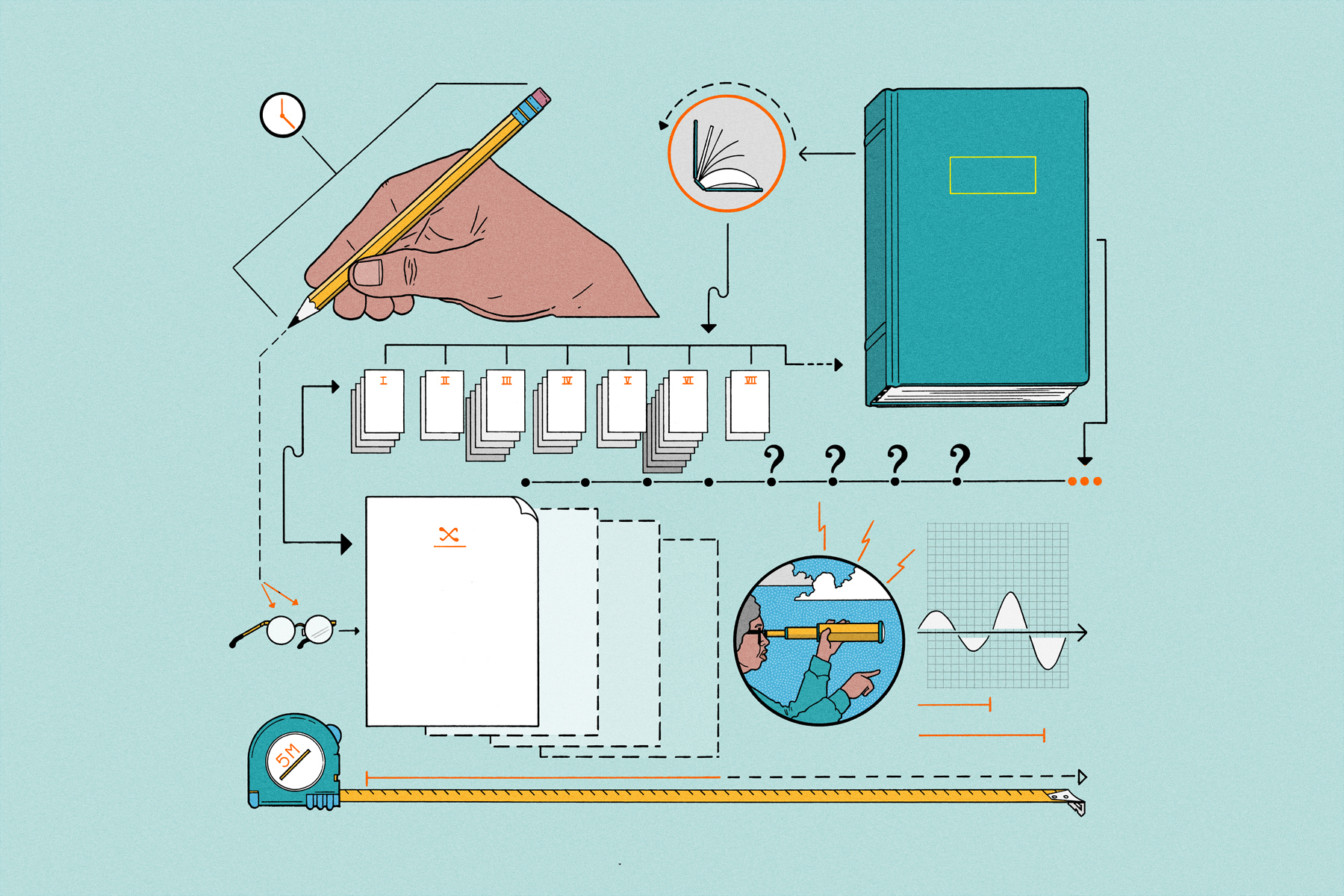

'Meta-work' is how we get past all the one-size-fits-none approaches

Alexandra Samuel points out in this newsletter that a lot of the work we do as knowledge workers will increasingly be ‘meta-work’. Introducing a 7-step approach, she first of all outlines why it’s necessary, especially in a ‘neurovarious’ world.

I think this is a really important article, and hits the sweet spot between AI literacy, systems thinking, and working openly. One to bookmark, for sure.

In the AI era, knowledge production will increasingly get done by machines—which means that the meta-work of choosing tools and processes is not just the work that remains for humans, but the most valuable kind of work you can do. Meta-work is how we get past all the one-size-fits-none approaches that have cursed us with overload and overwhelm, because we’re trying to work in a way that doesn’t don’t account for the vast differences in how each of us thinks, perceives, and communicates.

When we get overwhelmed by our tasks or stuck in our writing or thinking, it is often because we need to do some meta-work.

[…]

The more deeply I dive into the world of neurovariety—the functional differences in how workers think, perceive and communicate—the more I see that effective meta-work depends on understanding your own particular thinking, perception and communication style.

Meta-work requires you to think about how you build and create knowledge, to consider where you truly add value to your organization or to the world, and to recognize that there is no right answer to any of these questions—just the closest answer you can find for yourself, right now.

Source: Thrive at Work

Reimagining misinformation

Google’s new Pixel 9 smartphones are being heavily marketed as having their AI tool, Gemini , onboard. One of the things this allows you to do is to use a tool called ‘Reimagine’ that allows you to add new things to a scene simply via a text prompt.

It’s getting easier and easier to create realistic versions of events which never really happened. In the example above, they circumvented the cursory safeguards to simulate an accident. Fun times.

Reimagine is a logical extension of last year’s Magic Editor tools, which let you select and erase parts of a scene or change the sky to look like a sunset. It was nothing shocking. But Reimagine doesn’t just take it a step further — it kicks the whole door down. You can select any nonhuman object or portion of a scene and type in a text prompt to generate something in that space. The results are often very convincing and even uncanny. The lighting, shadows, and perspective usually match the original photo. You can add fun stuff, sure, like wildflowers or rainbows or whatever. But that’s not the problem.

A couple of my colleagues helped me test the boundaries of Reimagine with their Pixel 9 and 9 Pro review units, and we got it to generate some very disturbing things. Some of this required some creative prompting to work around the obvious guardrails; if you choose your words carefully, you can get it to create a reasonably convincing body under a blood-stained sheet.

In our week of testing, we added car wrecks, smoking bombs in public places, sheets that appear to cover bloody corpses, and drug paraphernalia to images. That seems bad. As a reminder, this isn’t some piece of specialized software we went out of our way to use — it’s all built into a phone that my dad could walk into Verizon and buy.

Source: The Verge

Where in the world is that shadow?

My son enjoys playing GeoGuessr, which is “a geography game, in which you are dropped somewhere in the world in a street view panorama and your mission is to find clues and guess your location on the world map”.

Some people are incredibly good at it, and can identify places within seconds. They use clues such as shadows, streetlights, and even the colour of soil or sand.

Bellingcat, an investigative journalism group specialising in “fact-checking and open-source intelligence” has released a tool to help figure out the location of images or video for more serious purposes. This is particularly important in a world of misinformation.

Geolocation is often a time-consuming task.

Researchers often spend hours poring over photos, scouring satellite images and sifting through street view.

But what if there was another way to quickly narrow down your search area?

Bellingcat’s new Shadow Finder Tool, developed with our Discord community, helps you quickly narrow down where an image was taken, by reducing your search area from the entire globe to just a handful of countries and locations.

Source: Bellingcat

Tool: Shadow Finder

Dark data is a climate concern

I mean, yes, of course I knew that data files are stored on servers and that those servers consume electricity. But this is a good example of reframing. How many emails have I got stored that I will never look at again? How many files stored in the cloud ‘just in case’?

Multiply that by millions (and billions) of internet users and we’ve got… a climate-relevant issue.

When “I can has cheezburger?” became one of the first internet memes to blow our minds, it’s unlikely that anyone worried about how much energy it would use up.

But research has now found that the vast majority of data stored in the cloud is “dark data”, meaning it is used once then never visited again. That means that all the memes and jokes and films that we love to share with friends and family – from “All your base are belong to us”, through Ryan Gosling saying “Hey Girl”, to Tim Walz with a piglet – are out there somewhere, sitting in a datacentre, using up energy. By 2030, the National Grid anticipates that datacentres will account for just under 6% of the UK’s total electricity consumption, so tackling junk data is an important part of tackling the climate crisis.

[…]

One funny meme isn’t going to destroy the planet, of course, but the millions stored, unused, in people’s camera rolls does have an impact, he explained: “The one picture isn’t going to make a drastic impact. But of course, if you maybe go into your own phone and you look at all the legacy pictures that you have, cumulatively, that creates quite a big impression in terms of energy consumption.”

Cloud operators and tech companies have a financial incentive to stop people from deleting junk data, as the more data that is stored, the more people pay to use their systems. “There are maybe other big contributors to [greenhouse gas] emissions, which maybe haven’t been picked up. And we would certainly argue that data is one of those and it will grow and get bigger, particularly think about that huge explosion but also, we know through forecasts that in the next year to two, if we take all the renewable energy in the world, that wouldn’t be enough to accommodate the amount of energy data requires. So that’s quite a scary thought.”

Source: The Guardian

Image: Nyan Cat

There is no such thing as a life that makes sense

I definitely agree with the author of this post that there a couple of wonderful things about reading history. First, you realise that almost everyone in the past had it much harder than you do, which puts things in perspective. Second, you realise that there’s many and varied ways to live a happy and/or flourishing life.

In addition, the passing comment about credentials not mattering when people realise you’re obsessive enough about a certain area is probably an insight worth unpacking.

Most of my friends have life paths that go something like this: they got ruinously obsessed with something to the exclusion of everything else and then worked on it. And eventually that failed or succeeded and then they got ruinously obsessed with something else and started working on that. And it turns out that if you’re obsessive enough the credentials thing sort of goes away because people are just like, oh, you’re clearly competent and bizarrely knowledgeable about this thing you’re obsessed with, I want to help you work on it.

If you operate like this way you end up with a weird life because in a conventional career path there are all these rules and customs you’re supposed to follow, like you’re supposed to major in W in undergrad and get X internship and then go to Y for grad school and then work at Z. The truth is, most of the people I know are just too ADHD or impatient or unconventional to follow the path that’s expected of them. They may not have even been aware of what the “normal” thing to do was. And I’m certainly not recommending that or glamorizing it because rules and customs exist for a reason, they are necessarily useful. But it’s helpful to know that some people end up fine even when they don’t do the normal thing.

Something I wish someone had told me as a kid is that the only real “rule” for work is that you have to be able pay your rent and not hurt anyone and not break any laws. And within those confines you can do literally anything, hopefully something you find personally fulfilling.

[…]

Reading history is useful partially because it makes you understand how varied people’s lives really are. The artists I admire have had lives that included nervous breakdowns and fleeing countries because of war and leaving their wife in another continent and writing their first novel to pay off gambling debts. That helps me remember that there is no such thing as a life that makes sense, or at least that’s not something I need to aspire to.

Source: bookbear express

Image: Derick McKinney

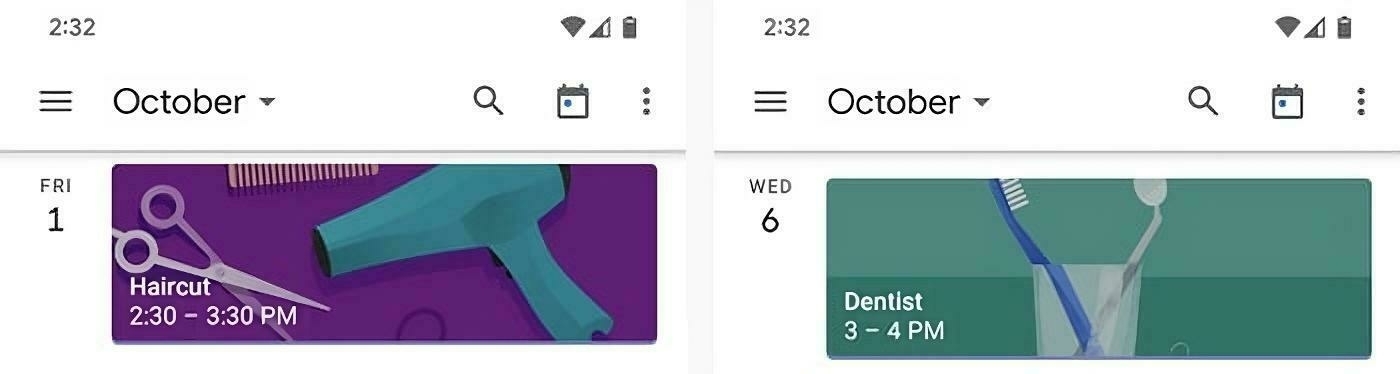

Google Calendar illustration trigger words

If you use the Google Calendar app in ‘schedule’ view, you’ll no doubt be familiar with the automatic illustrations added for some events. While looking for a way to stop it showing an American Football instead of a ‘soccer’ ball, I came across a list of all of the different kinds of ways you can trigger the illustrations.

Those illustrations are triggered by the presence of certain codewords within your event titles. And once you know what codewords cause what illustrations to appear, you can hack the system, in a sense, and make any event in your agenda stand out with a specific illustration around it.

Source: The Intelligence

(someone’s also created a GitHub repo)

You get water from food as well, you know

It’s always puzzled me when people drink huge amounts of water. Whether it’s for ‘detox’ reasons, as part of a diet, or something else, it always seems to be tinged with a bit of moral showboating.

I do a fair amount of exercise. I drink water with some BCAA powder in it when I do. Other than that, I have a couple of cups of tea a day and water with my meals. Turns out, this is probably the right approach.

It is a common belief that you have to drink 6-8 glasses of water per day. Almost everyone has heard this recommendation at some point although if you were to ask someone why you need to drink this much water every day, they probably wouldn’t be able to tell you. There is usually some vague idea that you need to drink water to flush toxins out of your system. Perhaps someone will suggest that drinking water is good for your kidneys since they filter the blood and regulate water balance. Unfortunately, none of these ideas is quite true and the 6-8 glasses myth comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of some basic physiology.

[…]

You will always lose water vapour in your breath, provided you keep breathing, and you will always produce… watery-odour free sweat even if you move to the Arctic. Of course, if you move to the tropics you will produce much more sweat to compensate for the extra heat. But all told, roughly 1.5-2 litres of water loss are obligatory losses that we cannot do anything about. Those who exercise, live in hot climates or have a fever will obviously lose more water because of more sweating. Thus, a human being needs to replenish the roughly 2 litres of water they lose every day from sweating, breathing, and urination. The actual notion of 8 glasses a day originates from a 1945 US Food and Nutrition Board which recommended 2.5 litres of daily water intake. But what is generally forgotten from this recommendation is, firstly, that it was not based on any research and that secondly the recommendation stated that most of the water intake could come from food sources.

All food has some water in it, although obviously fresh juicy fruits will have more than, say, a box of raisins. Suffice it to say that by eating regular food and having coffee, juice or what have you, you will end up consuming 2 litres of water without having to go seek it out specifically. If you find yourself in a water deficit, your body has a very simple mechanism for letting you know. Put simply, you will get thirsty.

If you are thirsty, drink water. If you are not thirsty, then you do not need to go out and purposefully drink 6-8 glasses of water a day since you will probably get all the water in your regular diet. One important caveat to remember though is that on hot summer days, your water losses from sweating go up and if you plan to spend some time out doors, having water with you is important to avoid dehydration and heat stroke. While the thirst reflex is pretty reliable, it does tend to fade with age and older people are more likely to become dehydrated without realizing it. Thus, the take home message is drink water when you are thirsty, but on very hot days it might not be a bad idea to stay ahead of the curve and keep hydrated.

Tugging at metaphors

Christina Hendricks is a Professor of Teaching in Philosophy at the University of British Columbia-Vancouver. In this post she reflects on a session run by fellow Canadian and open educator, Dave Cormier, in which he discussed ‘messy’ situations where we’re not sure what should be done.

The solution suggested seems to be to ‘tug’ things in a particular direction based on your values. I’d argue for a different, more systemic approach, given what I’ve learned so far through my MSc. What you need when confronted with a messy, problematic situation are boundaries, holistic thinking, and multiple perspectives.

I really appreciated where Dave landed in his presentation: rather than only feeling stuck, suspended, we can consult our values and make a move based on those, we can tug the rope in a tug of war in the direction of our values and work to move things from there. The focus on values is key here: ask yourself what are your values as they relate to this situation, and make decisions and act based on those, knowing that’s enough in uncertain situations. Which doesn’t mean, of course, that you can’t revisit your values and how they apply to the situation if either of those things changes, but that it’s a landing place and it’s solid enough for the moment. He talked about how we can have conversations with students and others about why we would do something in a particular situation, rather than what the right answer is, focusing on the values that are moving us.

To do so requires that we are clear about what our values are, which is in some cases more easily said than done. This is something near and dear to my heart as a philosopher, as trying to distill what is underlying our views and our decisions, what kinds of reasons and values, is part of our bread and butter.

[…]

[W]hat if we thought about complex issues and structures more like flexible webs? (Which is an image that reminds me of other of Dave Cormier’s work such as that on rhizomatic learning.) So that if you tug on one part it can still move and the other parts will move as well (or break I suppose, which in some cases may not be a bad thing).

Source: You’re The Teacher

Image: David Ellis (CC BY-NC-ND)

You don't need permission, you need advice

Deciding that you want to do something and then asking for advice is different to asking for permission. In general, permission-seeking behaviour in adults is a sign of weakness, even in hierarchical organisations. It’s either a sign of personal weakness, or if there are consequences for acting with authority in your domain of influence, then it’s a sign of organisational weakness.

One of the most common anti-patterns I see that can create conflict in an otherwise collaborative environment is people asking for permission instead of advice. This is such an insidious practice that it not only sounds reasonable, it actually sounds like the right thing to do: “Hey, I was thinking about doing X, would you be on board with that?”

Advice… is easy. “Hey, I was thinking about doing X, what advice would you give me on that?” In this instance you are showing a lot of respect to the person you are asking but not saddling them with responsibility because the decision is still on you. Your obvious goal with this approach is to do the best you can, so they are going to trust you aren’t hiding any gritty details and therefore aren’t going to waste time second guessing your premises. They are going to feel comfortable giving you all their honest feedback knowing the responsibility lies with you, and your ego will remain intact because you invited the criticism on yourself directly.

Source: boz

Image: Mark König

Give readers a break

I recently struggled with the middle of a book which I really wanted to finish by an author I really like. The chapters were too long for its subject matter, and I gave up.

Contrast that with The Road which is quite the harrowing read at times but, as this article points out, doesn’t have any chapters at all. I completed that without any problem. Other books, like the Reacher series, have quite short chapters. The trick, it seems, is to have chapter, or at least some kind of gaps to give readers a break, at times which are appropriate.

With our phones offering us immediate dopamine, books now have to work harder to keep us engaged. ‘Busy-ness’ has become an increasing distraction, through work and parenting as well as social media. That’s why you may have noticed shorter chapters in more recent books, especially ones aimed at readers of millennial age and below (that’s pretty much everyone under forty).

As any writer will find, however, there is no magic button when it comes to chapter length: the ‘right’ one is a blend for each novel being written. There’s no point in worrying about the length of your piece of string if the string itself isn’t useful or compelling.

Source: Penguin

14kB

It’s been four years since I switched to the Susty theme for my WordPress-powered blog. Not long later, I also redesigned my home page to be less than 1kB (although it’s slightly more than that now).

Micro.blog, which I use to host Thought Shrapnel is terrible in this regard. Using Cloudflare’s URL Scan gave a ‘bytes transferred’ total of 12.24MB, which is 3,000 times larger than the 4.15kB for my home page, and 14 times larger than the 891.28kB (including images) for my WordPress-powered blog.

Minimising the size of your site is is not only a good idea from a sustainability point of view, but having a fast-loading website is just better for user experience and SEO. The extract below explains why having a site that is less than 14KB (compressed) is a good idea from a technical perspective.

Most web servers TCP slow start algorithm starts by sending 10 TCP packets.

The maximum size of a TCP packet is 1500 bytes.

This maximum is not set by the TCP specification, it comes from the ethernet standard

Each TCP packet uses 40 bytes in its header — 16 bytes for IP and an additional 24 bytes for TCP

That leaves 1460 bytes per TCP packet. 10 x 1460 = 14600 bytes or roughly 14kB!

So if you can fit your website — or the critical parts of it — into 14kB, you can save visitors a lot of time — the time it takes for one round trip between them and your website’s server.

Source: endtimes.dev

Image: Markus Spiske

Doing things that don’t scale in pursuit of things that can’t scale

Note: I’ve been away from here for just over a month, and my backlog is so huge that I can’t put off posting any longer!

I’ve said many times over the last few years to friends and family that I’ve achieved all that I want to in life. That, I think, makes it easier to ‘pursue things that don’t scale’ — but so does studying philosophy from my teenage years onwards.

This post talks about “doing things that don’t scale in pursuit of things that can’t scale” which is a great way of saying doing things that are human-scale. One of the examples given in this post is knitting, which cited in an article in The Guardian as being an example of the kinds of arts and crafts that promote wellbeing.

To some extent, of course, all of this is borne of maturity, of life experience, and of approaching and then reaching middle-age.

Chasing scale seems to be a kind of early life affliction. The more you chase it, the bigger the thing you chase gets. Perhaps it’s a natural desire to see how important we can be or at least how important our creations can be to the world (and hence how important we can be by proxy …). A desire to take on a seemingly insurmountable challenge, perhaps a noble one (though not always), and see if we can conquer it.

Yet without limits, we try to find them. This is true on many levels, whether it’s about how big we want our creations to become or how people should be able to lead their personal lives or how much candy kids can eat after a Halloween haul. But I think having no limits is unnatural. Chasing scale to the level we do is too. Whether we succeed or not, it stresses the system and inevitably burns us out.

Then a new motivation seems to surface, a desire to pursue something that can’t scale. See, my theory is that chasing things that scale makes you need therapy, and the therapy is pursuing things that can’t scale. The antidote to burnout and the existential inquiry it brings seems to be doing things that don’t scale in pursuit of things that can’t scale. It becomes exciting not to see what you can do without limits, but to see what you can do with them.

What are these pursuits that can’t scale? They could be skills, like archery or chess or cooking. They could be close relationships, like making friends. Maybe it’s building a truckload of IKEA furniture. Or maybe it’s starting a local small business. These pursuits could be considered hobbies or something more serious. It doesn’t matter so much what it is than that it has a clear and visible ceiling.

Source: Working Theorys

Stand up for yourself. Challenge authority. Tell your rude co-worker to shut up.

I can’t say I’ve ever read Roxanne Gay’s Work Friend column for The New York Times during the last four years, but I enjoyed reading her sign-off article. She talks about the advice she really wanted to give people (usually “quit your job”) and the things that we really want, but will never be able to get, from a job.

To work, for so many of us, is to want, want, want. To want to be happy at work. To feel useful and respected. To grow professionally and fulfill your ambitions. To be recognized as leaders. To be able to share what you believe with the people you’re around for eight or more hours a day. To be loyal and hope your employers will reciprocate. To be compensated fairly. To take time off to recharge and enjoy the fruits of your labor. To conquer the world. To do a good enough job and coast through middle age to retirement.

[…]

We shouldn’t have to suffer or work several jobs or tolerate intolerable conditions just to eke out a living, but a great many of us do just that. We feel trapped and helpless and sometimes desperate. We tolerate the intolerable because there is no choice. We ask questions for which we already know the answers because change is terrifying and we can’t really afford to risk the loss of income when rent is due and health insurance is tied to employment and someday we will have to stop working and will still have financial obligations.

I was mindful of these realities as I answered your Work Friend questions. Still, in my heart of hearts, I always wanted to tell you to quit your job. Negotiate for the salary you deserve. Stand up for yourself. Challenge authority. Tell your rude co-worker to shut up. Report your boss to everyone and anyone who will listen. Consult a lawyer. Did I mention quit your job? Go back to graduate school. Leave some deodorant and mouthwash on your smelly co-worker’s desk. Send that angry email to your undermining colleague. Call out your boss when he makes a wildly inappropriate comment. No, your boss should not force you to work out of her kitchen. Mind your own business about your colleague’s weird hobby. Mind your own business, in general. Blow the damn whistle on your employer’s cutting corners and putting people’s lives in danger. Tell the irresponsible dog owner to learn how to properly care for the dog. No, you don’t owe your employer anything beyond doing your job well in exchange for compensation. No, your company is not your family. No, the job will never, ever love you.

This is all to say that I wish we lived in a world where I could offer you frank, unfiltered professional advice, but I know we do not live in such a world.

Source: Goodbye, Work Friends

(use Archive Buttons if you can’t access directly)

You don't have to like what other people like, or do what other people do

Warren Ellis responds to a post by Jay Springett on ‘surface flatness’ by reframing the problem as… not one we have to worry about. It’s good advice: so long as you can sustain an income by not having to interact with online walled gardens, why care what other people do?

(I’m saying this slightly hesitantly, as I often do hand-wringing about the amount of disinformation on mainstream social networks and chat apps, but there’s not much I personally can do about it)

If you treat all those internet platforms as television, then you can turn them off and go for a walk on the internet instead. Structured hypertext products are still walled gardens, they’re just themed gardens, like a physic garden. The thing about walled gardens is that most people like them. They’re easy.

Jay has a point about the big platforms generally deprecating a lot of hypertext functions, as they lead people out of the walled gardens. But people like walled gardens. Even if they’re full of toxic plants, stinking blooms and corpse flowers. And besides: you have no more hope of imposing a new way of doing things on the internet than of preventing the BBC from commissioning any new programme with Michael McIntyre in it.

Leave ’em to it. Network tv isn’t all of broadcast culture, just as the big platforms aren’t all of internet culture, and all that shit is still hyperlinked. Leave the platforms to it. Go for a walk and report your notes.

Source: Warren Ellis