2023

- Ask for what you want, even if it seems out of reach or like a big unreasonable request

- Take care of your own needs, and others will take care of theirs

- It’s fine to make requests that people will probably say no to

- People say yes to requests that you truly feel good about, say no to ones they don’t

- Only ask for something if you’re already pretty sure the other person will say yes

- Read an abundance of indirect contextual cues to determine if your request is reasonable to make

- It’s rude to put someone in a position where they have to say no to you

- If the appropriate feelers and context are set, you will never have to make your request at all.

The uninhabitable earth

This interactive tool maps in 3D where our planet will become unihabitable due to a combination of heat, water stress, sea level rise, and tropical cyclones.

It’s an amazing and depressing visualisation, which indirectly shows how climate migration will inevitably increase in the coming decades.

Climate change is destroying people's livelihoods. By the year 2100, all areas that are red in the visualisation will become “uninhabitable”. Extreme heat, tropical cyclones, rising sea levels, water stress or a combination of those are projected to make it difficult or impossible to live there.Source: Climate change: Mapping in 3D where the earth will become uninhabitable | Berliner Morgenpost

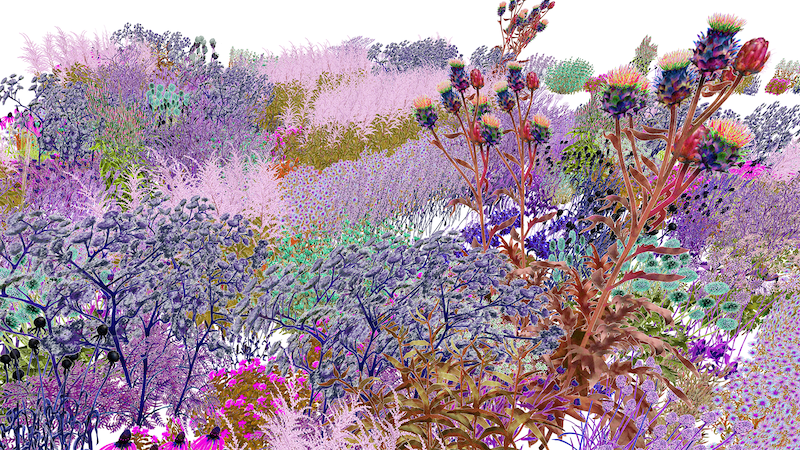

The world's largest climate-positive artwork provides food and nesting spots via algorithm

It’s interesting that this is being conceptualised as an ‘artwork’ rather than a technological intervention. Perhaps this is the way to deal with the climate crisis, by bringing algorithms from the cold, sterile environment of technology into the warmer, more joyful world of art?

This multidisciplinary project by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg explores the relationship between humans, nature, and technology and aims to draw attention to the importance of insects in pollination by creating an algorithmic solution for planting designs that serve a diverse range of pollinator species.

The project changes depending on location, debuting at the Eden Project in 2021 and includes 7,000 plants across 80 varieties. These provide food and nesting spots for insects with the aim to create the world’s largest climate-positive artwork.

This is not a natural ecosystem planted outside, there are plants from all over the world. With the expert group, we chose not to focus on native plants only because they are locally appropriate so they’re not invasive. So that’s the first thing—it’s an artificial landscape designed for nature, so it’s a very different way of creating an ecosystem. The other big challenge to the art world that I’m proposing is creating a climate-positive artwork. I also show in museums and I use digital media and that’s all very carbon-consuming. Here, we actually have an artwork fabricated in plants. It has its own climate impact because of the soil we’re moving, the plastic pots, the shipping of plants, but it’s here for at least three years, so it starts to outweigh that negative. There’s also a question of how we measure that, and that’s something I’m really interested in.Source: An Interview with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg | Berlin Art LinkThe other thing that’s really important to me is upending the idea of value. The art market is all about the one, the singular, the limited edition. This is an unlimited edition. The idea is: the more people who have one, the better each one is because each one supports the other. For me, that’s a strong statement to make to commissioners and when I’m trying to get more partners involved. It’s a very different way of thinking about how we create art and what its purpose is. For me, this is about playfulness, joy and celebrating nature. I call it an artwork and not a garden project because I think situating it in that context makes a powerful statement in itself.

AI and bullshit jobs

I had the pleasure of working with the large-brained Helen Beetham when I was at Jisc just over a decade ago. In this long-ish post, she covers quite a few areas of, with plenty of links, and pulls the threads together around graduate jobs and an AI curriculum.

While I could have quoted a lot of this, especially around innovation, the stories being told to graduates, and the neo-colonial nature of AI companies, I’ve gone for the last three paragraphs in which Helen discusses bullshit jobs. I’d highly recommend reading the whole thing.

My hope is that, rather than a curriculum ‘for AI’, these conversations would create space for learning that addresses human challenges. Getting life on earth out of the mess that fossil fuels and rampant production have made of it will take all the graduate labour we can produce and more. Nobody is going to be without meaningful work - not climate scientists or green energy specialists or engineers or geologists or computer scientists or materials chemists or statisticians. Not a single person educated in the STEM subjects beloved of governments everywhere can be left idle. But nor are we getting out of this without social scientists to help us weather the social and economic and political storms, humanities graduates to develop new laws and policies, new philosophies and imagined futures, and professionals committed to a just transition in their own spheres of work. And there are other crises, entwined with the climate crisis, that graduates need and want to address, such as galloping economic inequality, crises of democracy and human rights, food and water shortages, and the crisis of care. Universities can offer fewer and fewer guarantees of secure employment and decent pay, but they can offer meaningful work, justifying students’ investment in the future.Source: ‘Luckily, we love tedious work’ | Helen BeethamThe longer you look at the things ChatGPT can do, the more they resemble what David Graeber described as Bullshit Jobs - jobs that don’t need doing. While I don’t agree with the way he singles out specific job roles, Graeber is surely right that more and more work involves doing things with data and information and ‘content’ that has no value beyond maintaining those systems. And one claim he made that is borne out by workplace research is that meaningless work is bad for people’s mental health.

It’s a nice little aphorism that ‘if AI can do your job, AI should do your job’. But here’s a different one. If AI can ‘do’ your job, you deserve a better job. And if meaningless jobs are bad for workers’ mental health, how much worse are they for all our futures? The phrase ‘fiddling while Rome burns’ hardly begins to cover our present situation. As the polycrisis heats up, the crisis of not enough water-cooler text is not something any graduate should have to care about, nor any university curriculum either.

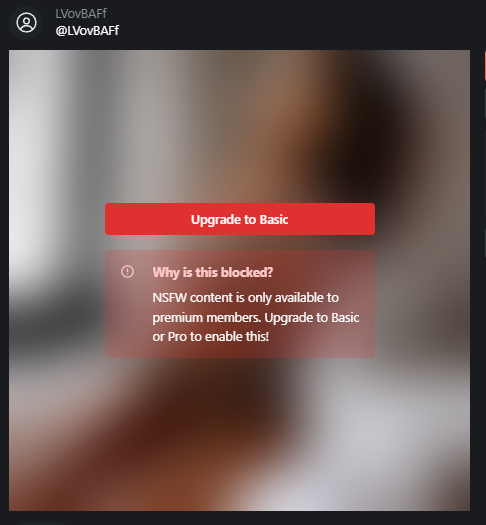

We need to talk about AI porn

Thought Shrapnel is a prude-free zone, especially as the porn industry tends to be a technological innovator. It’s important to say, though, that the objectification of women and non-consensual generation of pornography is not just a bad thing but societally corrosive.

By now, we’re familiar with AI models being able to create images of almost anything. I’ve read of wonderful recent advances in the world of architecture, for example. Some of the most popular AI generators have filters to prevent abuse, but of course there are many others.

As this article details, a lot of porn has already been generated. Again, prudishness aside relating to people’s kinks, there are all kind of philosophical, political, legal, and issues at play here. Child pornography is abhorrent; how is our legal system going to deal with AI generated versions? What about the inevitable ‘shaming’ of people via AI generated sex acts?

All of this is a canary in the coalmine for what happens in society at large. And this is why philosophical training is important: it helps you grapple with the implications of technology, the ‘why’ as well as the what. I’ve got a lot more thoughts on this, but I actually think it would be a really good topic to discuss as part of the next season of the WAO podcast.

“Create anything,” Mage.Space’s landing page invites users with a text box underneath. Type in the name of a major celebrity, and Mage will generate their image using Stable Diffusion, an open source, text-to-image machine learning model. Type in the name of the same celebrity plus the word “nude” or a specific sex act, and Mage will generate a blurred image and prompt you to upgrade to a “Basic” account for $4 a month, or a “Pro Plan” for $15 a month. “NSFW content is only available to premium members.” the prompt says.Source: Inside the AI Porn Marketplace Where Everything and Everyone Is for Sale | 404 Media[…]

Since Mage by default saves every image generated on the site, clicking on a username will reveal their entire image generation history, another wall of images that often includes hundreds or thousands of AI-generated sexual images of various celebrities made by just one of Mage’s many users. A user’s image generation history is presented in reverse chronological order, revealing how their experimentation with the technology evolves over time.

Scrolling through a user’s image generation history feels like an unvarnished peek into their id. In one user’s feed, I saw eight images of the cartoon character from the children’s’ show Ben 10, Gwen Tennyson, in a revealing maid’s uniform. Then, nine images of her making the “ahegao” face in front of an erect penis. Then more than a dozen images of her in bed, in pajamas, with very large breasts. Earlier the same day, that user generated dozens of innocuous images of various female celebrities in the style of red carpet or fashion magazine photos. Scrolling down further, I can see the user fixate on specific celebrities and fictional characters, Disney princesses, anime characters, and actresses, each rotated through a series of images posing them in lingerie, schoolgirl uniforms, and hardcore pornography. Each image represents a fraction of a penny in profit to the person who created the custom Stable Diffusion model that generated it.

[…]

Generating pornographic images of real people is against the Mage Discord community’s rules, which the community strictly enforces because it’s also against Discord’s platform-wide community guidelines. A previous Mage Discord was suspended in March for this reason. While 404 Media has seen multiple instances of non-consensual images of real people and methods for creating them, the Discord community self-polices: users flag such content, and it’s removed quickly. As one Mage user chided another after they shared an AI-generated nude image of Jennifer Lawrence: “posting celeb-related content is forbidden by discord and our discord was shut down a few weeks ago because of celeb content, check [the rules.] you can create it on mage, but not share it here.”

Raising the average level of creativity using AI

Like most infants, my daughter wanted to speak before she was able to. Unlike most infants, she was extremely frustrated that she couldn’t do so.

Most people can’t draw as well as they would like. Many people become exasperated when they can’t adequately express their ideas in written form.

AI can help with all of this and, in my case, already is. This article, which draws on the results of three academic studies, is interesting in terms of how we can raise the average level of human creativity with the use of AI.

Each of the three papers directly compares AI-powered creativity and human creative effort in controlled experiments. The first major paper is from my colleagues at Wharton. They staged an idea generation contest: pitting ChatGPT-4 against the students in a popular innovation class that has historically led to many startups. The researchers — Karan Girotra, Lennart Meincke, Christian Terwiesch, and Karl Ulrich — used human judges to assess idea quality, and found that ChatGPT-4 generated more, cheaper and better ideas than the students. Even more impressive, from a business perspective, was that the purchase intent from outside judges was higher for the AI-generated ideas as well! Of the 40 best ideas rated by the judges, 35 came from ChatGPT.Source: Automating creativity | Ethan MollickA second paper conducted a wide-ranging crowdsourcing contest, asking people to come up with business ideas based on reusing, recycling, or sharing products as part of the circular economy. The researchers (Léonard Boussioux, Jacqueline N. Lane, Miaomiao Zhang, Vladimir Jacimovic, and Karim R. Lakhani) then had judges rate those ideas, and compared them to the ones generated by GPT-4. The overall quality level of the AI and human-generated ideas were similar, but the AI was judged to be better on feasibility and impact, while the humans generated more novel ideas.

The final paper did something a bit different, focusing on creative writing ideas, rather than business ideas. The study by Anil R. Doshi and Oliver P. Hauser compared humans working alone to write short stories to humans who used AI to suggest 3-5 possible topics. Again, the AI proved helpful: humans with AI help created stories that were judged as significantly more novel and more interesting than those written by humans alone. There were, however, two interesting caveats. First, the most creative people were helped least by the AI, and AI ideas were generally judged to be more similar to each other than ideas generated by people. Though again, this was using AI purely for generating a small set of ideas, not for writing tasks.

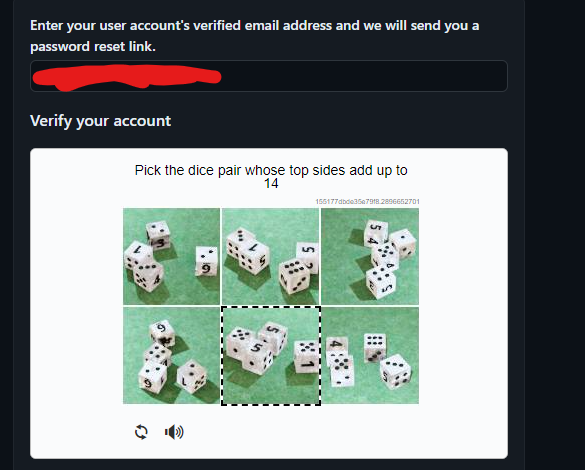

CAPTCHA is an arms race we're losing against AI bots

I saw a story that GitHub’s CAPTCHA had become ridiculously hard and multiple people weren’t able to solve it within the time limit. GitHub have presumably upgraded their system because the version we’ve come to know and despise (“click on all of the traffic lights”) is now solved faster by AI than by humans.

“Life is a campaign against malice” said the 17th century Jesuit priest and philosopher Baltasar Gracián. How right he was.

You definitely have tried to access some websites and have gotten bombarded with a series of puzzles requiring you to correctly identify traffic lights, buses, or crosswalks to prove that you’re indeed human before you log in.Source: AI bots are better than humans at solving CAPTCHA puzzles | QuartzKnown as Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart (CAPTCHA), the technology is intended to protect a website from fraud and abuse without creating friction. The puzzles are meant to ensure that only valid users are able to access the site and not automated invasions.

Google replaced CAPTCHA with a more advanced tool called reCAPTCHA in 2019, but the team’s technical lead Aaron Malenfant told the Verge at the time that the technology would no longer be viable in 10 years’ time because advanced tech would allow the Turing test to run in the background.

His prediction was right. Artificial Intelligence (AI) bots are fast-evolving and are now beating the reCAPTCHA methodology used to confirm the validity and personhood of the users of various websites. They do this by imitating how the human brain and vision work. In fact, AI bots are measuring up to humans, and even beating them, in numerous facets.

When it's getting too hot for plants to photosynthesize, you know we've got a problem

I used to run a site called extinction.fyi which documented the climate emergency. This definitely would have been an article I would have featured on there.

As would the news that French nuclear power stations had to stop running when the water in the rivers next to where they’re situated became too hot. The additional heat of water coming out of the cooling circuits would raise the temperature further, killing aquatic life.

Leaves in the world’s tropical forests are approaching critical temperatures at which photosynthesis breaks down—and a fraction have likely already passed that threshold—raising alarms about the fate of these essential ecosystems under the most pessimistic projections of human-driven climate change, reports a new study.Source: It’s Getting Too Hot for Tropical Trees to Photosynthesize, Scientists Warn | VICE[…]

The ECOSTRESS data, along with follow-up measurements from the ground, showed that tropical canopy temperatures tend to peak at around 34°C, though some regions experienced temperatures that exceeded 40°C. Because there is a surprising amount of temperature variation between the individual leaves on a single tree, the researchers estimated that about a tenth of a percent of all leaves in tropical forests are annually pushed beyond the critical threshold of 46.7°C that marks the breaking point of photosynthesis.

[…]

As global temperatures continue to rise, more tropical leaves will be pushed beyond their photosynthetic capabilities, causing plants to perish. While the researchers emphasized that there is a lot of uncertainty in their models, they warned that an increase in global air temperatures of about 3.9°C could trigger a major photosynthetic meltdown for tropical forests. This estimated increase is within the range of climate models that project a future where human greenhouse gas emissions don’t begin to fall until after 2080.

Structural insecurity

This fantastic piece by Astra Taylor, whose book The Age of Insecurity is on my to-read list, is sadly behind a paywall. I managed to bypass it, which is why I’m excerpting so much in this post.

What I like is the separation of inequality from insecurity and the difference between existential insecurity from ‘manufactured’ insecurity. Being published in The New York Times, the context is the American economy which largely exists without a social safety net.

The situation is better in the UK/Europe, but we still live in a much more economically precarious world than our parents and grandparents did. And perhaps that’s why everyone’s anxious all of the time.

Since 2020, the richest 1 percent has captured nearly two-thirds of all new wealth globally — almost twice as much money as the rest of the world’s population. At the beginning of last year, it was estimated that 10 billionaire men possessed six times as much wealth as the poorest three billion people on Earth. In the United States, the richest 10 percent of households own more than 70 percent of the country’s assets.Source: Why Does Everyone Feel So Insecure All the Time? | The New York TimesSuch statistics are appalling. They have also become familiar. Since it was catapulted onto the national stage more than a decade ago by Occupy Wall Street, “inequality” has been a frequent topic of conversation in American political life. It helped animate Bernie Sanders’s influential campaigns, reshaped academic scholarship, shifted public policy, and continues to galvanize protest. And yet, however important focusing on the inequality crisis has been, it has also proven insufficient.

If we want to understand contemporary economic life, we need a more expansive framework. We need to think about insecurity. Where inequality encourages us to look up and down, to note extremes of indigence and opulence, insecurity encourages us to look sideways and recognize potentially powerful commonalities.

If inequality can be captured in statistics, insecurity requires talking about feelings: It is, to borrow a phrase from feminism, personal as well as political. Economic issues, I’ve come to realize, are also emotional ones: the spike of shame when a bill collector calls, the adrenaline when the rent or mortgage is due, the foreboding when you think about retirement.

And unlike inequality, insecurity is more than a binary of haves and have-nots. Its universality reveals the degree to which unnecessary suffering is widespread — even among those who appear to be doing well. We are all, to varying degrees, overwhelmed and apprehensive, fearful of what the future might have in store. We are on guard, anxious, incomplete and exposed to risk. To cope, we scramble and strive, shoring ourselves up against potential threats. We work hard, shop hard, hustle, get credentialed, scrimp and save, invest, diet, self-medicate, meditate, exercise, exfoliate.

[…]

Rather than something to pathologize, I want us to see insecurity as an opportunity. We all need protection from life’s hazards, natural or human-made. The simple acceptance of our mutual vulnerability — of the fact that we all need and deserve care throughout our lives — has potentially transformative implications. When we spur people on with insecurity because we expect the worst from them, we create a vicious cycle that stokes desperation and division while facilitating the kind of cutthroat competition and consumption that has brought our fragile planet to a catastrophic brink. When we extend trust and support to others, we improve everyone’s security — including our own.

[…]

Insecurity, after all, is what makes us human, and it is also what allows us to connect and change. “Nothing in Nature ‘becomes itself’ without being vulnerable,” writes the physician Gabor Maté in “The Myth of Normal.” “The mightiest tree’s growth requires soft and supple shoots, just as the hardest-shelled crustacean must first molt and become soft.” There is no growth, he observes, without emotional vulnerability.

The same also applies to societies. Recognizing our shared existential insecurity, and understanding how it is currently used against us, can be a first step toward forging solidarity. Solidarity, in the end, is one of the most important forms of security we can possess — the security of confronting our shared predicament as humans on this planet in crisis, together.

Emoji, we salute you 🫡

I remember going to a conference session about a decade ago when people were still on the fence about emoji and the presenter said that they were the most important form of visual communication since hieroglyphics.

It’s hard to argue otherwise. I’ve been a huge fan since I noticed that adding a smiley to my emails made a huge difference to the way that people received and understood them. It’s a way of communication at a distance; how would we navigate group chats and social networks without them? 😅

Valeria Pfeifer is a cognitive scientist at the University of Arizona. She is one of a small group of researchers who has studied how emojis affect our thinking. She tells me that my newfound joy makes sense. Emojis “convey this additional complex layer of meaning that words just don’t really seem to get at,” she says. Many a word nerd has fretted that emojis are making us—and our communication—dumber. But Pfeifer and other cognitive scientists and linguists are beginning to explain what makes them special.Source: Your 🧠 On Emoji | NautilusIn a book called The Emoji Code, British cognitive linguist Vyvyan Evans describes emojis as “incontrovertibly the world’s first truly universal communication.” That might seem like a tall claim for an ever-expanding set of symbols whose meanings can be fickle. But language evolves, and these ideograms have become the lingua franca of digital communication.

[…]

Perhaps the first study of how these visual representations activate the brain was presented at a conference in 2006.1 Computer scientist Masahide Yuasa, then at Tokyo Denki University in Japan, and his colleagues wanted to see whether our noggins interpret abstract symbolic representations of faces—emoticons made of punctuation marks—in the same way as photographic images of them. They popped several college students into a brain scanning machine (they used functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI) and showed them realistic images of happy and sad faces, as well as scrambled versions of these pictures. They also showed them happy and sad emoticons, along with short random collections of punctuation.

The photos lit up a brain region associated with faces. The emoticons didn’t. But they did activate a different area thought to be involved in deciding whether something is emotionally negative or positive. The group’s later work, published in 2011, extended this finding, reporting that emoticons at the end of a sentence made verbal and nonverbal areas of the brain respond more enthusiastically to written text.2 “Just as prosody enriches vocal expressions,” the researchers wrote in their earlier paper, the emoticons seemed to be layering on more meaning and impact. The effect is like a shot of meaning-making caffeine—pure emotional charge.

Hacking the vagus nerve

It looks like electric stimulation of the vagus nerve using something like a TENS machine could help with everything from obesity and depression to Long Covid.

One of the universities local to me is leading some of this work, and they have a page about it here.

From plunging your face into icy water, to piercing the small flap of cartilage in front of your ear, the internet is awash with tips for hacking this system that carries signals between the brain and chest and abdominal organs.Source: The key to depression, obesity, alcoholism – and more? Why the vagus nerve is so exciting to scientists | The Guardian[…]

Meanwhile, scientific interest in vagus nerve stimulation is exploding, with studies investigating it as a potential treatment for everything from obesity to depression, arthritis and Covid-related fatigue. So, what exactly is the vagus nerve, and is all this hype warranted?

The vagus nerve is, in fact, a pair of nerves that serve as a two-way communication channel between the brain and the heart, lungs and abdominal organs, plus structures such as the oesophagus and voice box, helping to control involuntary processes, including breathing, heart rate, digestion and immune responses. They are also an important part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs the “rest and digest” processes, and relaxes the body after periods of stress or danger that activate our sympathetic “fight or flight” responses.

[…]

Search “vagus nerve hacks” on TikTok, and you’ll be bombarded with tips ranging from humming in a low voice to twisting your neck and rolling your eyes, to practising yoga or meditation exercises.

Researchers who study the vagus nerve are broadly sceptical of such claims. Though such techniques may help you to feel calmer and happier by activating the autonomic nervous system, the vagus nerve is only one component of that. “If your heart rate slows, then your vagus nerve is being stimulated,” says Tracey. “However, the nerve fibres that slow your heart rate may not be the same fibres that control your inflammation. It may also depend on whether your vagus nerves are healthy.”

Similarly, immersing your face in cold water may also slow down your heart rate by triggering something called the mammalian dive reflex, which also triggers breath-holding and diverts blood from the limbs to the core. This may serve to protect us from drowning by conserving oxygen, but it involves sympathetic and parasympathetic responses.

Electrical stimulation may hold greater promise though. One thing that makes the vagus nerves so attractive is surgical accessibility in the neck. “It is quite easy to implant some device that will try to stimulate them,” says Dr Benjamin Metcalfe at the University of Bath, who is studying how the body responds to electrical vagus nerve stimulation. “The other reason they’re attractive is because they connect to so many different organ systems. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that vagus nerve stimulation will treat a wide range of diseases and disorders – everything from rheumatoid arthritis through to depression and alcoholism.”

Reality and the templated life

This article reviews a book entitled A Web of Our Own Making by Antón Barba-Kay which reminded me a lot of an issue of Audrey Watters' Second Breakfast newsletter about the templated body.

What does it mean for there to be multiple, constructed realities. When everyone has a smartwatch and is tracking everything, does that make their life both qualitatively and quantitatively different?

Some of these observations, though apt, aren’t exactly new — that the possibility of tracking our steps for so-called health reasons distorts our relationship with a simple country walk, that the fundamentally data-driven nature of smartphone culture “is such as to translate larger human questions about how to live into technical puzzles that may be ‘problem-solved,’” that Twitter timelines and Instagram feeds have become a saccharine way of capturing our limited and precious attention by distracting us from the less immediately rewarding elements of being human.Source: How the Internet obeys you | The New AtlantisBut the fusillade intensity with which Barba-Kay produces these inconvenient truths renders them impossible to ignore; from the details we start to perceive, little by little, the devil. As Barba-Kay writes, “digital technology is training us not simply to a new sense of what is real and really good, but to a new understanding of the contrasts within which we see that reality.” In other words, our awareness of what the virtual world cannot do has made us hungrier for those elements of reality from which we have not yet become alienated.

If reality is changing, it is because, for better and for worse, our lives are increasingly determined by one specific vision of human ingenuity: a vision that valorizes those elements of human life we freely choose (or think we do) over those we once saw as given to us — our bodies, our families, our communities. Digital culture functions today as the Enlightenment cosmopolis once did: as a fantasy in which society reshapes itself along the lines of affinity.

[…]

“Where once it was occasionally possible to opt out of ‘reality’ (by taking drugs, say),” Barba-Kay writes in the book’s perhaps most chilling line, “it is now increasingly necessary to think about how to opt in to it.” And we need to. It may be the most important decision we make in our lives.

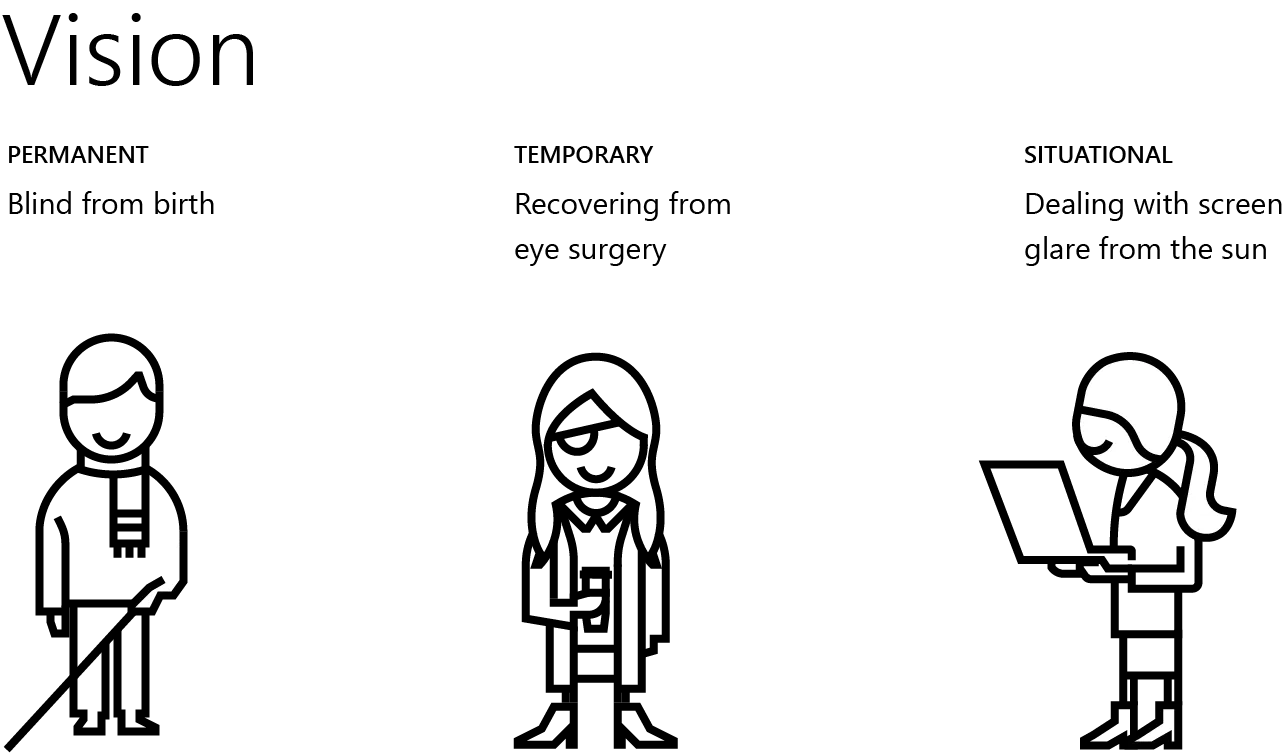

Temporarily Abled

This blog post which reflects on Cindy Li’s pithy quotation that “we’re all just temporarily abled”. I’m recovering from a rib injury sustained on holiday, so I feel the author’s pain. Hopefully it won’t take me months to recover, but it’s impacting my exercise regime and mental outlook.

It reminded me of a post on the Microsoft Design blog called Kill Your Personas which dives into temporarily disabilities. Definitely worth a read.

June 6th I was on vacation at the beach with my family and tried something that, looking back now, maybe I’m too old for. And I injured my knee.Source: “We’re All Just Temporarily Abled” | Jim Nielsen’s Blog[…]

That was almost three months ago now. I’m still limping. It’s getting better but it’s slow. The doctor told me, “Just be aware: this isn’t days or weeks recovery. This is months.”

Since then, I’ve tried to make the best of summer while kids are out of school but my mobility has been limited.

Through all of it, I’ve found myself noticing “accessibility” helpers more than ever before: that railing on the stairs, that ramp off to the side of the building, that elevator tucked away in the back.

All things I rarely noticed before but have since become vital.

And that phrase plays on repeat in my head — “we’re all just temporarily abled”.

[…]

I suppose it’s easy to misunderstand ability as a binary thing. But now I’m understanding more how fluid it is, as it inevitably comes in and out of each of our lives — “100% of people” in their lifetimes.

In classic human fashion, it’s one of those things you take for granted until it’s gone.

The only way to outlaw encryption is to outlaw encryption

An enjoyable take by The Register on the UK’s Online Safety Bill. I was particularly interested by the link to Veilid, a new secure peer-to-peer network for apps which is like the offspring of IPFS and Tor.

Many others have made the point about how much government ministers like the end-to-end encryption of their own WhatsApp communications. But they’d also like to break into, well… everyone else’s.

The official madness over data security is particularly bad in the UK. The British state is a world class incompetent at protecting its own data. In the past couple of weeks alone, we have seen the hacking of the Electoral Commission, the state body in charge of elections, the mass exposure of birth, marriage and death data, and the bulk release of confidential personnel information of a number of police forces, most notably the Police Service Northern Ireland. This was immediately picked up by terrorists who like killing police. It doesn't get worse than that.Source: Last rites for UK’s ridiculous Online Safety Bill | The RegisterThis same state is, of course, the one demanding that to “protect children,” it should get access to whatever encrypted citizen communication it likes via the Online Safety Bill, which is now rumored to be going through British Parliament in October. This is akin to giving an alcoholic uncle the keys to every booze shop in town to “protect children”: you will find Uncle in a drunken coma with the doors wide open and the stock disappearing by the vanload.

[…]

It is just stupidity stacked on incompetence balanced on political Dunning Krugerism, and the advent of Veilid drowns the lot in a tidal wave of foetid futility. What can a government do about a framework? What can it do about open source?

[…]

The only way to outlaw encryption is to outlaw encryption. Anything less will fail, as it is always possible in software to create kits of parts, all legal by themselves, that can be linked together to provide encryption with no single entity to legislate against. Our industry is fully aware of this. Criminals know it too. Ordinary people will learn it as well, if they have to. This information is free to everyone – except the politicians, it seems. For them, reality is far too expensive.

On 'Executive Function Theft'

This post by Abigail Goben popped up in several places and is one of those that gives a name to someone most people will recognise. It’s an important differentiation on what is often called ‘care work’ as it highlights how something important is taken when repetitive, administrative work is outsourced to other humans.

Executive Function Theft (EFT) is the deliberate abdication of decision-making, tasks, and responsibilities that are perceived as administrative or repetitive, of lesser importance, or aren’t pleasant or shiny, to another person, with the result that the receiving person’s executive function becomes so exhausted that they are unable to participate in, contribute to, or enjoy higher level efforts.Source: Executive Function Theft | Hedgehog Librarian[…]

In the workplace, an example of EFT often plays out in the inequality of service labor, and I will specifically use academic service work here as it is my current workplace. Think of the people who end up with more than their share of administrative maintenance tasks — such as organizing get well cards, scheduling workshops, or taking notes. Consider the colleague who has a list of committee appointments a yard long and has just gotten a request to be on Another! Important! (is it?) Committee. These individuals may not be doing these tasks strictly because it is their job responsibility, but because they see a need to be filled or have been asked or tasked with taking on more service that they feel they cannot turn down. And notice how those tasks so often fall to the same group of people — especially when we get to any form of implementation or ongoing commitment rather than the “fun” ideation phase. One way to calculate these service loads would be to count the number of committees and task forces held by and expected of various individuals — who gets a pass and who gets penalized if they don’t say yes.

Quite often there’s a gendered component as to who is tasked with these additional service responsibilities — the office housekeeping as well as the care tasks of the workplace.

[…]

I will admit to never having been able to read Cal Newport’s Deep Work all the way through — I got too irritated — but I would point to his dismissive naming of the idea of “shallow work”, which he defines as logistical and often repetitive tasks, such as writing short emails. Newport recommends entirely stopping or poorly performing that work; I read this as encouraging readers to commit EFT against others around them. Too often the dump off of what are critical responsibilities is not to a specifically tasked and appreciated administrator but instead onto the junior, female, minoritized, non-tenure track, or precarious employees. It’s the maintenance work of keeping the workplace going and we do not appreciate the maintainers. Similarly thinking about EFT in the workplace, I was reminded of the guy who got famous with the Four Hour Workweek book and how we were all just supposed to outsource things to nameless underpaid gig workers. Notably, when looking for a summary of that book, I found an article by Cal Newport praising it.

Image: Uday Mittal

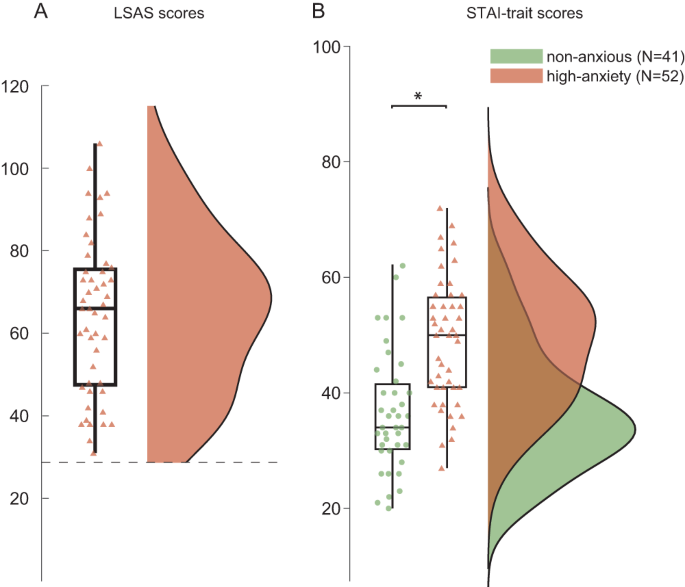

Why anxious people find it difficult to control their emotions

This explains a lot. Basically, studies have found that a specific part of the brain behaves differently in anxious individuals, and this difference might explain why they struggle with emotional control. It’s like a traffic jam in the brain that makes it harder for the signals to get through, leading to difficulties in managing emotional reactions.

Anxious individuals consistently fail in controlling emotional behavior, leading to excessive avoidance, a trait that prevents learning through exposure. Although the origin of this failure is unclear, one candidate system involves control of emotional actions, coordinated through lateral frontopolar cortex (FPl) via amygdala and sensorimotor connections. Using structural, functional, and neurochemical evidence, we show how FPl-based emotional action control fails in highly-anxious individuals. Their FPl is overexcitable, as indexed by GABA/glutamate ratio at rest, and receives stronger amygdalofugal projections than non-anxious male participants. Yet, high-anxious individuals fail to recruit FPl during emotional action control, relying instead on dorsolateral and medial prefrontal areas. This functional anatomical shift is proportional to FPl excitability and amygdalofugal projections strength. The findings characterize circuit-level vulnerabilities in anxious individuals, showing that even mild emotional challenges can saturate FPl neural range, leading to a neural bottleneck in the control of emotional action tendencies.Source: Anxious individuals shift emotion control from lateral frontal pole to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Nature Communications

Jobs, AI, and human worth

I’m sharing this article to make a comment about the framing for these kinds of things. The article is an extract from a book by David Runciman, and implicitly links human worth to jobs.

Part of the existential dread of AI replacing humans is that, if your job is your life, then who are you without the doing? Instead of hand-wringing about robots and machines, perhaps our time is better spent figuring out who we are and how we want to flourish.

In the slew of reports published in the 2010s looking to identify which jobs were most at risk of being automated out of existence, sports officials usually ranked very high up the list (the best known of these studies, by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne in 2017, put a 98% probability on sports officiating being phased out by computers within 20 years). Here, after all, is a human enterprise where the single most important qualification is an ability to get the answer right. In or out? Ball or strike? Fair or foul? These are decisions that need to be underpinned by accurate intelligence. The technology does not even have to be state-of-the-art to produce far better answers than humans can. Hawk-Eye systems have been outperforming human eyesight for nearly 20 years. They were first officially adopted for tennis line calls in 2006, to check cricket umpire decisions in 2009 and, more recently, to rule on football offsides.Source: The end of work: which jobs will survive the AI revolution? | The Guardian[…]

Efficiency – even accuracy – turns out not to be the main requirement of the organisations that employ people to give decisions during sports games. They are also highly sensitive to appearance, which includes a wish to keep their sport looking and feeling like it’s still a human-centred enterprise. Smart technology can do many things, but in the absence of convincingly humanoid robots, it can’t really do that. So actual people are required to stand between the machines and those on the receiving end of their judgments. The result is more work all round.

[…]

How things look isn’t everything. There are significant parts of every organisation where appearance doesn’t matter so much, in the backrooms and maybe even the boardrooms that the public never gets to see. Behind-the-scenes technical knowledge that underpins the performance of public-facing tasks is likely to be an increasingly precarious basis for reliable employment. This is true of many professions, including accountancy, consultancy and the law. There will still be lots of work for the people who deal with people. But the business of gathering data, processing information and searching for precedents can now more reliably be done by machines. The people who used to undertake this work, especially those in entry-level jobs such as clerks, administrative assistants and paralegals, might not be OK.

[…]

History offers a partial guide to what might happen. Worries about automation displacing human workers are as old as the idea of the job itself. The Industrial Revolution disrupted many kinds of labour – especially on the land – and undid entire ways of life. The transition was grim for those who had to switch from one mode of subsistence existence to another. Yet the end result was many more jobs, not fewer. Factories brought in machines to do faster and more reliably what humans used to do or could never do at all; at the same time, factories were where the new jobs appeared, involving the performance of tasks that were never required before the coming of the machines. This pattern has repeated itself time and again: new technology displaces familiar forms of work, causing massively painful disruption. It is little consolation to the people who lose their jobs to be told that soon enough there will be entirely new ways of earning a living. But there will.

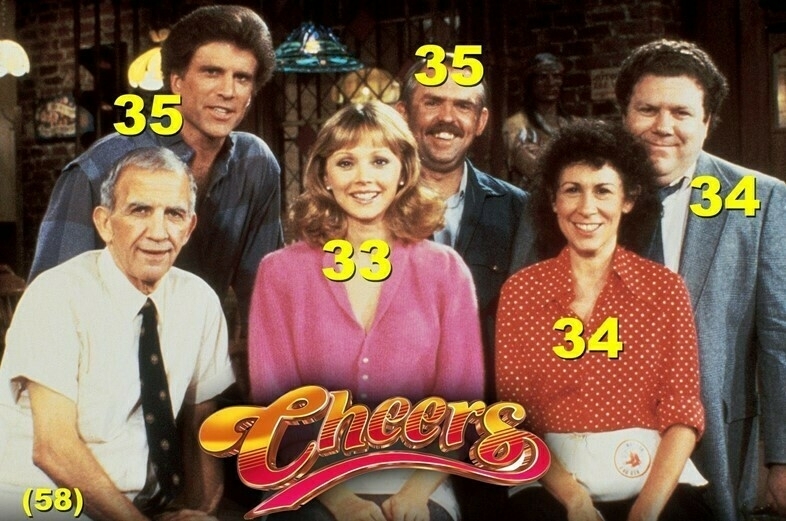

Did people in the past look older for their age?

I’m 42 but look much younger than my father did at his age. And I’m sure that he looked younger than my grandfather did at his age. This is an interesting article about why.

There’s a meme that makes the rounds every so often. It’s a group shot of the cast of 80s sitcom Cheers, with the ages of each actor displayed on the image. Every time it comes back around, people express surprise and disbelief that this group of what looks to be middle-aged folk are actually in their twenties and thirties. With his greying moustache and receding hairline, John Ratzenberger looks far older than what we might now imagine a 30-something man to look like – current 35-year-old actors Michael Cera and Nicholas Braun, for example, look significantly younger in comparison.Source: Why did people in the past look so much older? | Dazed[…]

While factors like diet, skincare and aesthetic procedures can make us physically look younger – hairstyles, make-up and fashion also play a role in how youthful we appear. While someone with 2023-esque micro bangs may scream young to us, we associate photos of 80s hairstyles and big shoulder pads with being older, even if the person in the image is the same age as us. This is partly because of how we consider trendy hairstyles and fashion of that time to be outdated.

[…]

Today we might be obsessed with preserving our youth, but this wasn’t always the case. In past decades, popular trends often existed to make young people appear more sophisticated and bold. “The dramatic nature of [80s] hairstyles often conveyed a sense of confidence and authority, which could be associated with older individuals,” hairdresser Gwenda Harmon says. “Certain hairstyles of the 1980s actually made some youth appear older due to their bold and sophisticated nature.”

Ask culture vs guess culture

I’ve seen this culture clash outlined before, although I wouldn’t necessarily use the labels ‘ask’ and ‘guess for the different approaches. I was raised by a mother who very much (still!) relies on inference to live her life. I’ve found being much more direct useful in living my own.

(I’d also note that the author seems to be playing fast-and-loose with the term ‘Western’ to mean ‘American’ here as British people are much more likely to be guessers than askers in my experience.)

Ask culture and guess culture are vastly different in behavior and expectations. Here are some highlights:Source: Ask vs guess culture | Tech and TeaAsk culture expectations

Guess culture expectations

[...]

If you’re more a guess-culture person, asking people for help without knowing their circumstances can feel rude or intrusive. Broadcasting publicly your need for help can feel awkward and vulnerable.

[…]

Western society is very much ask culture. A classic example can be found in proverbs. “A squeaky wheel gets the grease” is an American proverb, enforcing the ideas of individualism and that asking for what you want will benefit you.

Life in 2050

Futurist Stowe Boyd imagines life in 2050, through three scenarios. I can’t help but think that ‘Collapseland’ (excerpted below) is the most likely outcome. Sadly.

Collapseland is where everything goes pear shaped. Dithering by governments and corporations has allowed climate change to push the world into increased heat, drought, and violent weather. The Human Spring of the 2020s led to a conservative backlash and a suppression of the movement itself. It also led to a suppression of advancements in AI, since it became associated with the science orientation of the movement.Source: What Will a Corporation Look Like in 2050? | WIREDBut governments and corporations get their act together in the late 2020s and 2030s to avert an extinction event via the global adoption of solar. However, this only comes after a serious ecological catastrophe has occurred. Inequality remains unchecked, and the poor become much poorer.

Collapseland businesses are much like businesses of 2015. Most efforts are directed toward basic requirements — like desalinating water, relocating people away from low-lying or drought stricken areas, and struggling with food production challenges. As a result, little innovation has taken place. It’s no different from the company you work for today, except longer hours, fewer co-workers, less pay, and much more dust. To increase profits, corporations have cut staff and forced existing workers to work harder.

Context is everything, especially with books

When I was younger I slogged through some terrible books that, because they were deemed ‘classics’, I thought I should read. Thankfully, I’m a lot more ruthless with non-fiction and, in fact, these days I’m happy to give up on a book I’m not finding enjoyable/relevant after 50 pages.

The interesting thing, though, is that it’s always worth coming back to books. Sometimes, a change in interest, age, or context can completely change your relationship with them.

I used to believe that every book has an objective value. And I used to believe that this value is fixed and universal.Source: Is this a good book for me, now? | Mary Rose CookNow, I believe it’s much more useful to say something in this form: this book has this value to this person in this context.

[…]

The idea that a book’s value is best judged alongside the notional reader and their current context has some corollaries:

First, reading the books that your heroes cite as important will not necessarily be rewarding. If you admire Bret Victor for his work on computing interfaces, only some of his library will be high value to you because his library also includes lots of books that have nothing to do with UI.

Second, yes, it’s likely that “great books” may be high value in some more universal sense that is independent of reader and context. And, yes, this high value may come from something inherent in the quality of the books, rather than from the fact that they are about themes that are more relevant to more people. Yes, I probably wouldn’t dispute this. But I suspect that relevance to person and context is a better guide to what to read.

Third, book recommendation systems based on your reading history can be helpful, but only so much. You, now, are not represented by your reading history. You’ve changed. Making recommendations based on books you read twenty years ago might produce good books for you, now. But probably not.

Image: Thought Catalog