Jobs, AI, and human worth

I’m sharing this article to make a comment about the framing for these kinds of things. The article is an extract from a book by David Runciman, and implicitly links human worth to jobs.

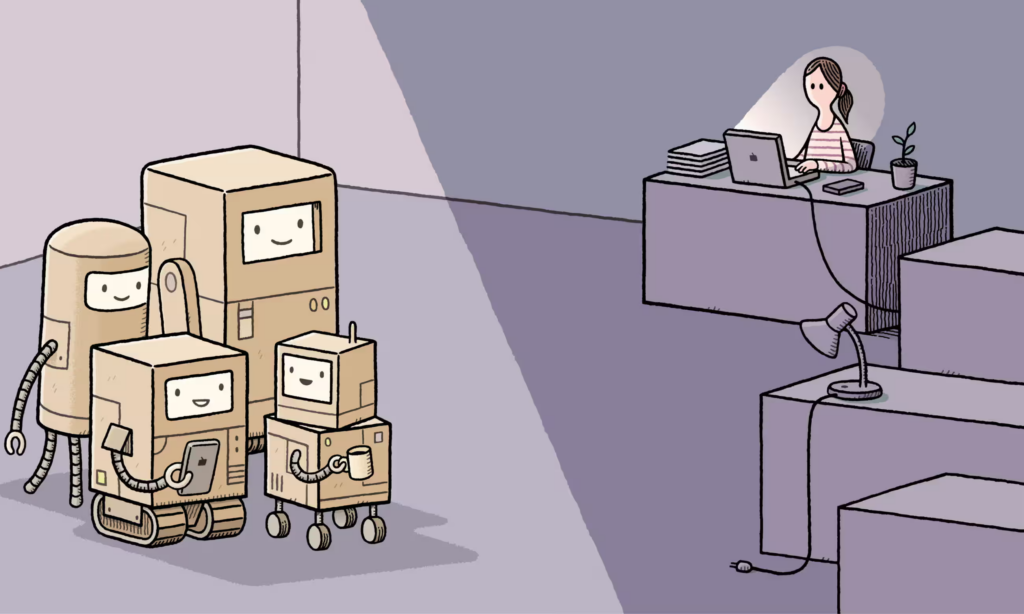

Part of the existential dread of AI replacing humans is that, if your job is your life, then who are you without the doing? Instead of hand-wringing about robots and machines, perhaps our time is better spent figuring out who we are and how we want to flourish.

In the slew of reports published in the 2010s looking to identify which jobs were most at risk of being automated out of existence, sports officials usually ranked very high up the list (the best known of these studies, by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne in 2017, put a 98% probability on sports officiating being phased out by computers within 20 years). Here, after all, is a human enterprise where the single most important qualification is an ability to get the answer right. In or out? Ball or strike? Fair or foul? These are decisions that need to be underpinned by accurate intelligence. The technology does not even have to be state-of-the-art to produce far better answers than humans can. Hawk-Eye systems have been outperforming human eyesight for nearly 20 years. They were first officially adopted for tennis line calls in 2006, to check cricket umpire decisions in 2009 and, more recently, to rule on football offsides.Source: The end of work: which jobs will survive the AI revolution? | The Guardian[…]

Efficiency – even accuracy – turns out not to be the main requirement of the organisations that employ people to give decisions during sports games. They are also highly sensitive to appearance, which includes a wish to keep their sport looking and feeling like it’s still a human-centred enterprise. Smart technology can do many things, but in the absence of convincingly humanoid robots, it can’t really do that. So actual people are required to stand between the machines and those on the receiving end of their judgments. The result is more work all round.

[…]

How things look isn’t everything. There are significant parts of every organisation where appearance doesn’t matter so much, in the backrooms and maybe even the boardrooms that the public never gets to see. Behind-the-scenes technical knowledge that underpins the performance of public-facing tasks is likely to be an increasingly precarious basis for reliable employment. This is true of many professions, including accountancy, consultancy and the law. There will still be lots of work for the people who deal with people. But the business of gathering data, processing information and searching for precedents can now more reliably be done by machines. The people who used to undertake this work, especially those in entry-level jobs such as clerks, administrative assistants and paralegals, might not be OK.

[…]

History offers a partial guide to what might happen. Worries about automation displacing human workers are as old as the idea of the job itself. The Industrial Revolution disrupted many kinds of labour – especially on the land – and undid entire ways of life. The transition was grim for those who had to switch from one mode of subsistence existence to another. Yet the end result was many more jobs, not fewer. Factories brought in machines to do faster and more reliably what humans used to do or could never do at all; at the same time, factories were where the new jobs appeared, involving the performance of tasks that were never required before the coming of the machines. This pattern has repeated itself time and again: new technology displaces familiar forms of work, causing massively painful disruption. It is little consolation to the people who lose their jobs to be told that soon enough there will be entirely new ways of earning a living. But there will.