An end to rabbit hole radicalization?

A new peer-reviewed study suggests that YouTube’s efforts to stop people being radicalized through its recommendation algorithm have been effective. The study monitored 1,181 people’s YouTube activity and found that only 6% watched extremist videos, with most of these deliberately subscribing to extremist channels.

Interestingly, though, the study cannot account for user behaviour prior to YouTube’s 2019 algorithm changes, which means we can only wonder about how influential the platform was in terms of radicalization up to and including pretty significant elections.

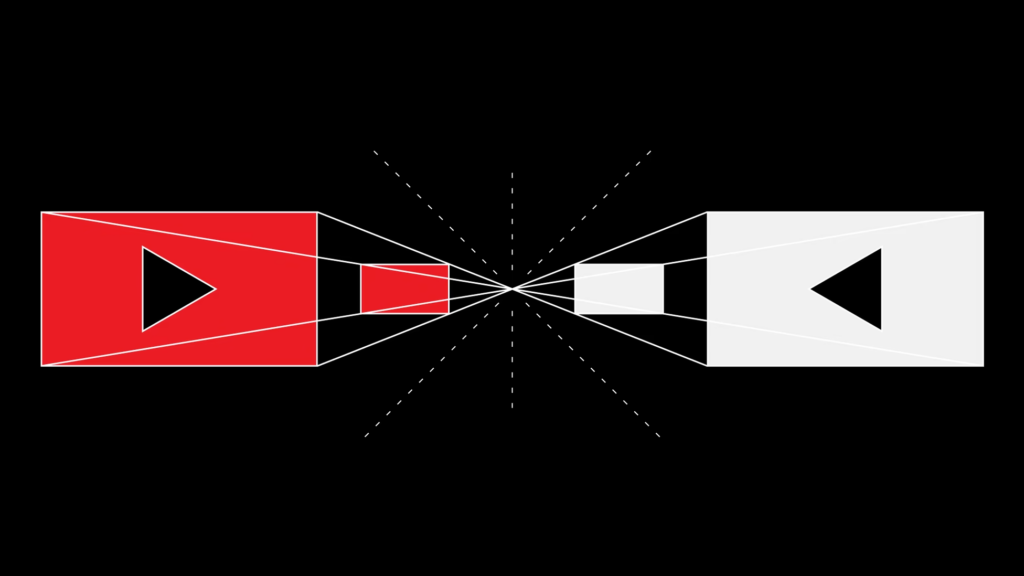

Around the time of the 2016 election, YouTube became known as a home to the rising alt-right and to massively popular conspiracy theorists. The Google-owned site had more than 1 billion users and was playing host to charismatic personalities who had developed intimate relationships with their audiences, potentially making it a powerful vector for political influence. At the time, Alex Jones’s channel, Infowars, had more than 2 million subscribers. And YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, which accounted for the majority of what people watched on the platform, looked to be pulling people deeper and deeper into dangerous delusions.Source: The World Will Never Know the Truth About YouTube’s Rabbit Holes | The AtlanticThe process of “falling down the rabbit hole” was memorably illustrated by personal accounts of people who had ended up on strange paths into the dark heart of the platform, where they were intrigued and then convinced by extremist rhetoric—an interest in critiques of feminism could lead to men’s rights and then white supremacy and then calls for violence. Most troubling is that a person who was not necessarily looking for extreme content could end up watching it because the algorithm noticed a whisper of something in their previous choices. It could exacerbate a person’s worst impulses and take them to a place they wouldn’t have chosen, but would have trouble getting out of.

[…]

The… research is… important, in part because it proposes a specific, technical definition of ‘rabbit hole’. The term has been used in different ways in common speech and even in academic research. Nyhan’s team defined a “rabbit hole event” as one in which a person follows a recommendation to get to a more extreme type of video than they were previously watching. They can’t have been subscribing to the channel they end up on, or to similarly extreme channels, before the recommendation pushed them. This mechanism wasn’t common in their findings at all. They saw it act on only 1 percent of participants, accounting for only 0.002 percent of all views of extremist-channel videos.

Nyhan was careful not to say that this paper represents a total exoneration of YouTube. The platform hasn’t stopped letting its subscription feature drive traffic to extremists. It also continues to allow users to publish extremist videos. And learning that only a tiny percentage of users stumble across extremist content isn’t the same as learning that no one does; a tiny percentage of a gargantuan user base still represents a large number of people.