Curiosity, projectories, and AI

I’ve read a lot of danah boyd’s work over the years, especially given how her research interests intersect with my work. In this long-ish post, she argues for an approach to AI driven by curiosity and the concept of ‘projectories’ (subject to guardrails).

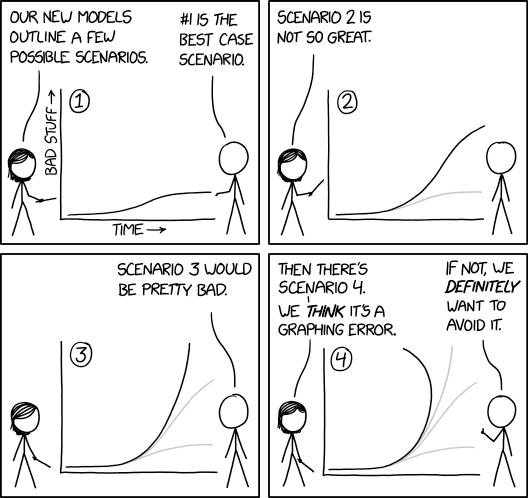

I just returned from a three month sabbatical spent mostly offline diving through history and I feel like I’ve returned to an alien planet full of serious utopian and dystopian thinking swirling simultaneously. I find myself nodding along because both the best case and worst case scenarios could happen. But also cringing because the passion behind these declarations has no room for nuance. Everything feels extreme and fully of binaries. I am truly astonished by the the deeply entrenched deterministic thinking that feels pervasive in these conversations.Source: Resisting Deterministic Thinking | danah boyd[…]

The key to understanding how technologies shape futures is to grapple holistically with how a disruption rearranges the landscape. One tool is probabilistic thinking. Given the initial context, the human fabric, and the arrangement of people and institutions, a disruption shifts the probabilities of different possible futures in different ways. Some futures become easier to obtain (the greasing of wheels) while some become harder (the addition of friction). This is what makes new technologies fascinating. They help open up and close off different possible futures.

[...]

Even though deterministic thinking can be extraordinarily problematic, it does have value. Studying the scientists and engineers at NASA, Lisa Messeri an Janet Vertesi describe how those who embark on space missions regularly manifest what they call “projectories.” In other words, they project what they’re doing now and what they’re working on into the future in order to create for themselves a deterministic-inflected roadplan. Within scientific communities, Messeri and Vertesi argue that projectories serve a very important function. They help teams come together collaboratively to achieve majestic accomplishments. At the same time, this serves as a cognitive buffer to mitigate against uncertainty and resource instability. Those of us on the outside might reinterpret this as the power of dreaming and hoping mixed with outright naiveté.

[...]

Where things get dicy is where delusional thinking is left unchecked. Guard rails are important. NASA has a lot of guardrails, starting with resource constraints and political pressure. But one of the reasons why the projectories of major AI companies is prompting intense backlash is because there are fewer other types of checks within these systems. (And it’s utterly fascinating to watch those deeply involved in these systems beg for regulation from a seemingly sincere place.)

[...]

Rather than doubling down on deterministic thinking by creating projectories as guiding lights (or demons), I find it far more personally satisfying to see projected futures as something to interrogate. That shouldn’t be surprising since I’m a researcher and there’s nothing more enticing to a social scientist than asking questions about how a particular intervention might rearrange the social order.

[...]

I, for one have no clue what’s coming down the pike. But rather than taking an optimistic or a pessimistic stance, I want to start with curiosity. I’m hoping that others will too.