2022

- Supply – how many opportunities we encounter

- Response – whether we notice those opportunities and how we respond to them

- Growth – whether and how we internalise the result of our encounters with serendipity

Professional try-hards

I love this article about, variously, work-life balance, the future of work, quiet quitting, and the ridiculousness of Silicon Valley culture. To be honest, I feel very fortunate to not have to put up with any of this bullshit in my day-to-day work.

[T]he future of white-collar work has morphed from an advertiser-friendly thought exercise to an existential question with a daily subset of moral riddles: Is that an illicit midday nap, or is it just work-life balance? Is it really the end of work friends, or is it just that a defensive herd mentality is no longer crucial to getting through the day? Is it worse to work on vacation, or to have a little vacation at work? Is the delivery bot lost in the woods, or is he finally free?Source: The Professional Try-Hard Is Dead, But You Still Need to Return to the Office | Vanity Fair[…]

I’d love to be flip and just say that, at this point in planetary decline, anyone who’s a little too interested in emails and Google Docs basically counts as a try-hard, but there’s a specific category of salaryfolk and company leadership provoking a justifiable kind of scorn. The professional try-hard I’m talking about is someone who, in the year 2022, still earnestly and performatively buys into the white-collar hustle and prides themselves on it. You know this person. They’re a cross between a teacher’s pet and a supply-room narc; if they’re not already a manager, they certainly aim to be one day. While everyone else got with the program that trying hard at work—against a political and national backdrop that feels like daily, endless crisis—is ridiculous, or worse, meaningless, these guys (it’s not exclusively a male thing, of course, but I’m not not being gendered on purpose) haven’t quite gotten with the program.

[…]

What’s clear—and what’s behind the reason that professional try-hards are flailing so fantastically—is that the very concept of corporate competence itself has become a joke. The ideals that white-collar striving is built upon have started to crumble: Imagine believing in true “innovation” in a world where Meta, formerly the most exciting company on earth, is reduced to hitting copy and paste. Imagine still buying into the corporate ladder in any sector where performance evaluations might be rife with racial disparities, or where the executives have essentially admitted on the stand that their entire industry is just a game of roulette. Imagine having faith at all in any idea of “corporate good” when the guy celebrated for years as the “one moral CEO in America” is now the subject of a rape investigation (that CEO has denied the allegations). Just last month, Adam Neumann, the disgraced WeWork founder whose implosion was so well-documented that it got turned into prestige television, reportedly received a $350 million second chance for pretty much the same idea he rode to ruin last time.

Imagine, in other words, believing anyone in charge knows what they’re doing. But okay, sure, sic the productivity-management software on everyone else to make sure we’re not online shopping a touch too much.

Professional try-hards

I love this article about, variously, work-life balance, the future of work, quiet quitting, and the ridiculousness of Silicon Valley culture. To be honest, I feel very fortunate to not have to put up with any of this bullshit in my day-to-day work.

[T]he future of white-collar work has morphed from an advertiser-friendly thought exercise to an existential question with a daily subset of moral riddles: Is that an illicit midday nap, or is it just work-life balance? Is it really the end of work friends, or is it just that a defensive herd mentality is no longer crucial to getting through the day? Is it worse to work on vacation, or to have a little vacation at work? Is the delivery bot lost in the woods, or is he finally free?Source: The Professional Try-Hard Is Dead, But You Still Need to Return to the Office | Vanity Fair[…]

I’d love to be flip and just say that, at this point in planetary decline, anyone who’s a little too interested in emails and Google Docs basically counts as a try-hard, but there’s a specific category of salaryfolk and company leadership provoking a justifiable kind of scorn. The professional try-hard I’m talking about is someone who, in the year 2022, still earnestly and performatively buys into the white-collar hustle and prides themselves on it. You know this person. They’re a cross between a teacher’s pet and a supply-room narc; if they’re not already a manager, they certainly aim to be one day. While everyone else got with the program that trying hard at work—against a political and national backdrop that feels like daily, endless crisis—is ridiculous, or worse, meaningless, these guys (it’s not exclusively a male thing, of course, but I’m not not being gendered on purpose) haven’t quite gotten with the program.

[…]

What’s clear—and what’s behind the reason that professional try-hards are flailing so fantastically—is that the very concept of corporate competence itself has become a joke. The ideals that white-collar striving is built upon have started to crumble: Imagine believing in true “innovation” in a world where Meta, formerly the most exciting company on earth, is reduced to hitting copy and paste. Imagine still buying into the corporate ladder in any sector where performance evaluations might be rife with racial disparities, or where the executives have essentially admitted on the stand that their entire industry is just a game of roulette. Imagine having faith at all in any idea of “corporate good” when the guy celebrated for years as the “one moral CEO in America” is now the subject of a rape investigation (that CEO has denied the allegations). Just last month, Adam Neumann, the disgraced WeWork founder whose implosion was so well-documented that it got turned into prestige television, reportedly received a $350 million second chance for pretty much the same idea he rode to ruin last time.

Imagine, in other words, believing anyone in charge knows what they’re doing. But okay, sure, sic the productivity-management software on everyone else to make sure we’re not online shopping a touch too much.

Every complex problem has a solution which is simple, direct, plausible — and wrong

This is a great article by Michał Woźniak (@rysiek) which cogently argues that the problem with misinformation and disinformation does not come through heavy-handed legislation, or even fact-checking, but rather through decentralisation of funding, technology, and power.

I really should have spoken with him when I was working on the Bonfire Zappa report.

While it is possible to define misinformation and disinformation, any such definition necessarily relies on things that are not easy (or possible) to quickly verify: a news item’s relation to truth, and its authors’ or distributors’ intent.Source: Fighting Disinformation: We’re Solving The Wrong Problems / Tactical Media RoomThis is especially valid within any domain that deals with complex knowledge that is highly nuanced, especially when stakes are high and emotions heat up. Public debate around COVID-19 is a chilling example. Regardless of how much “own research” anyone has done, for those without an advanced medical and scientific background it eventually boiled down to the question of “who do you trust”. Some trusted medical professionals, some didn’t (and still don’t).

[…]

Disinformation peddlers are not just trying to push specific narratives. The broader aim is to discredit the very idea that there can at all exist any reliable, trustworthy information source. After all, if nothing is trustworthy, the disinformation peddlers themselves are as trustworthy as it gets. The target is trust itself.

[…]

I believe that we are looking for solutions to the wrong aspects of the problem. Instead of trying to legislate misinformation and disinformation away, we should instead be looking closely at how is it possible that it spreads so fast (and who benefits from this). We should be finding ways to fix the media funding crisis; and we should be making sure that future generations receive the mental tools that would allow them to cut through biases, hoaxes, rhetorical tricks, and logical fallacies weaponized to wage information wars.

Every complex problem has a solution which is simple, direct, plausible — and wrong

This is a great article by Michał Woźniak (@rysiek) which cogently argues that the problem with misinformation and disinformation does not come through heavy-handed legislation, or even fact-checking, but rather through decentralisation of funding, technology, and power.

I really should have spoken with him when I was working on the Bonfire Zappa report.

While it is possible to define misinformation and disinformation, any such definition necessarily relies on things that are not easy (or possible) to quickly verify: a news item’s relation to truth, and its authors’ or distributors’ intent.Source: Fighting Disinformation: We’re Solving The Wrong Problems / Tactical Media RoomThis is especially valid within any domain that deals with complex knowledge that is highly nuanced, especially when stakes are high and emotions heat up. Public debate around COVID-19 is a chilling example. Regardless of how much “own research” anyone has done, for those without an advanced medical and scientific background it eventually boiled down to the question of “who do you trust”. Some trusted medical professionals, some didn’t (and still don’t).

[…]

Disinformation peddlers are not just trying to push specific narratives. The broader aim is to discredit the very idea that there can at all exist any reliable, trustworthy information source. After all, if nothing is trustworthy, the disinformation peddlers themselves are as trustworthy as it gets. The target is trust itself.

[…]

I believe that we are looking for solutions to the wrong aspects of the problem. Instead of trying to legislate misinformation and disinformation away, we should instead be looking closely at how is it possible that it spreads so fast (and who benefits from this). We should be finding ways to fix the media funding crisis; and we should be making sure that future generations receive the mental tools that would allow them to cut through biases, hoaxes, rhetorical tricks, and logical fallacies weaponized to wage information wars.

WFH from anywhere

Winter in the UK isn’t much fun, so if we didn’t have kids I would absolutely be working from a different country for part of it. Why not?

This is not a new thing: when I worked at Mozilla (2012-15) I almost moved to Gozo, a little island off Malta, as I could work from anywhere. So long as people are productive, and you can interact with them at times that work for everyone, what’s the problem?

Two-plus years into the pandemic, companies all around the world are starting to ask—and sometimes demand—that their employees return to the office. In response, many employees have resisted, citing reduced commute times, better work-life balance, and a greater ability to concentrate at home.Source: Some WFH Employees Have a Secret: They Now Live in Another Country | VICEBut for an unknown number of people, there is another reason as well: They can’t come in, because they secretly don’t live in the same state or even country anymore.

The issue is larger than it may seem, and many companies are struggling to deal with “employees relocating themselves to ‘nicer’ places to work without letting the business know,” said Robby Wogan, the CEO of global mobility company MoveAssist. One survey performed on behalf of the HR company Topia found that as many as 40 percent of HR professionals had recently discovered that employees were working outside their home state or country, and that only 46 percent were “very confident” they know where most of their workers are, down from 60 percent just last year.

That uncertainty appears justified. In the same survey, 66 percent of the 1,500 full-time employees surveyed in the U.S. and U.S. said they did not tell human resources about all the dates they worked outside of their state or country, and 94 percent said they believe they should be able to work wherever they want if their work gets done.

Paying it forward

It’s worth clicking through to the Axios summary of some recent research showing that people underestimate the impact of small acts of kindness.

I notice this in my own life: when I’m driving, if another driver smiles and allows me to merge into the queue, I’m more likely to do it to others; if I check in on people and ask how they’re doing, they more likely to do it to me. And so on.

Small and simple, kind gestures have immense, underestimated power.Source: The outsized power of small acts of kindness

CDNs are not phone books

The notorious website kiwi farms is no longer being protected by Cloudflare’s CDN (Content Delivery Network). This means that it is itself subject to DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks and other cybersecurity risks.

It’s been a long time coming. I agree with Ryan Broderick’s take on this, that websites are like street corners, and it helps them to be conceptualised as such.

Prince said that Cloudflare’s security services, many of which are free and are used by an estimated 20 percent of the entire internet, should be thought of as a utility. “Just as the telephone company doesn't terminate your line if you say awful, racist, bigoted things, we have concluded in consultation with politicians, policy makers, and experts that turning off security services because we think what you publish is despicable is the wrong policy,” Prince wrote.Source: A website is a street corner | by Ryan BroderickWhich is a good line. I’m sure people who are old enough to remember when telephones weren’t computers love it. But I’m not really sure it works here. Telephones are not publishing platforms, nor are they searchable public records. Comparing a message board that has around nine million visitors a month to someone saying something racist on the telephone is, actually, nuts.

But, more broadly, I don’t even think this is a free speech issue. Cloudflare isn’t a government entity and it’s not putting Kiwi Farms members in jail. In fact, it seems like some users have done that themselves. A German woman seems to have accidentally exposed her real identity amid the constant migration of the site and now may be charged for cyberstalking. Instead, Cloudflare, a private company, has removed their protection from the site, which allows activists and hackers to DDoS it, taking it down.

[…]

Websites are not similar to telephones. They are not even similar to books or magazines. They are street corners, they are billboards, they are parks, they are shopping malls, they are spaces where people congregate. Just because you cannot see the (hopefully) tens of thousands of other people reading this blog post right now doesn’t mean they’re not there. And that is doubly true for a user-generated content platform. And regardless of the right to free speech and the right to assemble guaranteed in America, if the crowd you bring together in a physical space starts to threaten people, even if they’re doing it in the periphery of your audience, the private security company you hired as crowd control no longer has to support you. To me, it’s honestly just that simple.

Image: Karol Smoczynski | Unsplash

Ad-free urban spaces

I've never understood why we allow so much advertising in our lives. Thankfully, I live in a small town without that much of it, but it's always a massive culture shock when I go to a city. So I very much support this campaign led by Charlotte Gage of Adfree Cities.

Related: over the last few years, I've got my kids into the habit of pressing the mute button during advert breaks on TV. This makes the adverts seem even more ridiculous, allows for conversation, and still allows you to see when the programme you're watching comes back on!

"These ads are in the public space without any consultation about what is shown on them," she says. "Plus they cause light pollution, and the ads are for things people can't afford, or don't need."

Ms Gage is the network director of UK pressure group Adfree Cities, which wants a complete ban on all outdoor corporate advertising. This would also apply to the sides of buses, and on the London Underground and other rail and metro systems.

[...]

Ms Gage says that while there are "ethical issues with junk food ads, pay day loans and high-carbon products [in particular], people would rather see community ads and art rather than have multi-billion dollar companies putting logos and images everywhere".

Ad-free urban spaces

I've never understood why we allow so much advertising in our lives. Thankfully, I live in a small town without that much of it, but it's always a massive culture shock when I go to a city. So I very much support this campaign led by Charlotte Gage of Adfree Cities.

Related: over the last few years, I've got my kids into the habit of pressing the mute button during advert breaks on TV. This makes the adverts seem even more ridiculous, allows for conversation, and still allows you to see when the programme you're watching comes back on!

"These ads are in the public space without any consultation about what is shown on them," she says. "Plus they cause light pollution, and the ads are for things people can't afford, or don't need."

Ms Gage is the network director of UK pressure group Adfree Cities, which wants a complete ban on all outdoor corporate advertising. This would also apply to the sides of buses, and on the London Underground and other rail and metro systems.

[...]

Ms Gage says that while there are "ethical issues with junk food ads, pay day loans and high-carbon products [in particular], people would rather see community ads and art rather than have multi-billion dollar companies putting logos and images everywhere".

You should only ever be busy on purpose

If you’re consistently over-stretched, you’re doing it wrong. And if you’re not doing it wrong, your organisation is.

If you are too busy, why? What are you and your team in pursuit of? If you are too busy because of pressure imposed by someone else, why do they believe they should be able to ask more of you?Source: Why are you so busy? | Tom LinghamAre you too busy because the business has expectations for you to deliver by a certain date regardless of the capacity of your team (who are delivering high quality work and always working on the next most important thing as prioritised by the business)? Then that is a conversation that you need to have with your boss and your stakeholders. That is likely unreasonable.

[…]

You and your team should never be so busy that you can’t do your job properly or that you begin to hate your work. Especially if you’re a leader or a leader-of-leaders, then you should actually (yes you should, I’ll die on this hill) have free time to think alone, and to talk and ideate organically with peers. Contrary to popular belief: back-to-back meetings isn’t a badge of honour, it’s a red flag.

Image: DALL-E 2

The art of a cup of tea

There’s something about having a cup of tea that’s very different to having a cup of coffee. They’re both a means to an end, but the ends differ massively.

The point is that even if you are the kind of person who wants to do nothing, the world today will seemingly not leave you alone to your languid contemplation and staring out of the window nothingness. It is unacceptable, it’s bad for the economy, it’s somehow letting the side down. So in my pretty vast experience of being an idler in a world of strivers I have found that you need some sort of prop to handle while doing nothing. This explains the enduring, never-to-be-fully-extinguished appeal of the cigarette break and it’s more wholesome cousin, the subject of today’s discussion, the lovely cup of tea.Source: On Tea and the Art of Doing Nothing | Thomas J Bevan[…]

If you are sleep deprived tea will not give you a jolt of fleeting alertness to get through another day and help delay confronting the issue that you aren’t getting enough quality sleep. If you have masses of work and a tight deadline, tea will not give you a ‘Limitless’ style ability to get it done despite the odds. If anything tea could slow you down. I can’t envision a montage in one of those interminable, never-ending TV series where the group of lawyers or programmers or detectives have to pull an all-nighter beginning with the team getting out the single origin Assam and their best China.

[…]

We intuitively know that the tea itself is probably a nothing in and by itself, and that it probably does nothing in and by itself, but that this a nothing we can ritualise and return to as a refuge from the pressures of the day to day. In a world overstuffed with disorder and frantic activity, calm is found not in a location but in a ritual. It is found by enjoying an end-in-itself pleasure that promises nothing but itself. And that’s all it needs to be.

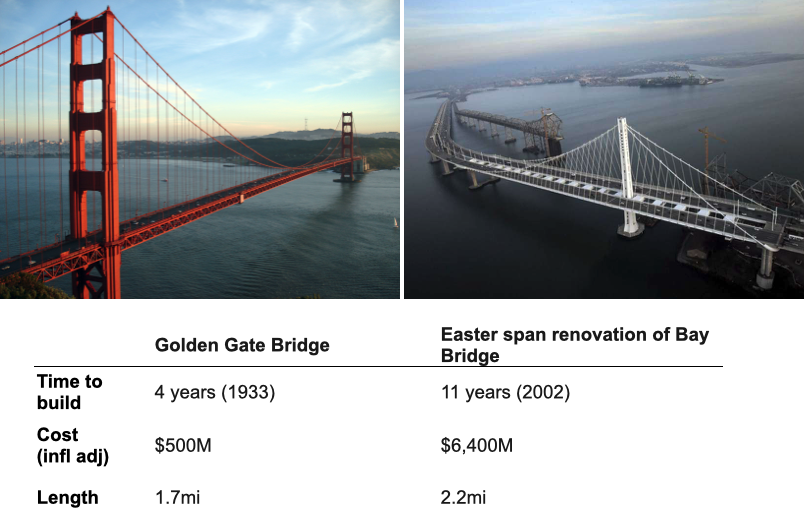

Against 'talkocracy'

Research. Build. Test. Repeat.

Not endless talking and pontification.

Everywhere I look, I see the rise of talkocracy — others have called it the dictatorship of the articulate. Talkers standing in the way of builders; offering we ponder, analyze, investigate, research, dissect, agonize endlessly over plans before we lay a single brick.Source: The Dictatorship of the Articulate | Florent Crivello[…]

This endless pondering introduces years and years of unnecessary delays. But worse: it kills the will to build. There is nothing builders hate more than endless meetings with people who can’t even spell “CPU.”

You know you’ve lost when they’ve internalized the conservative voices, which can now stop them without even having to try. It’s when your intern has a neat idea for something he could hack together in a few hours — but then thinks, what’s the point?

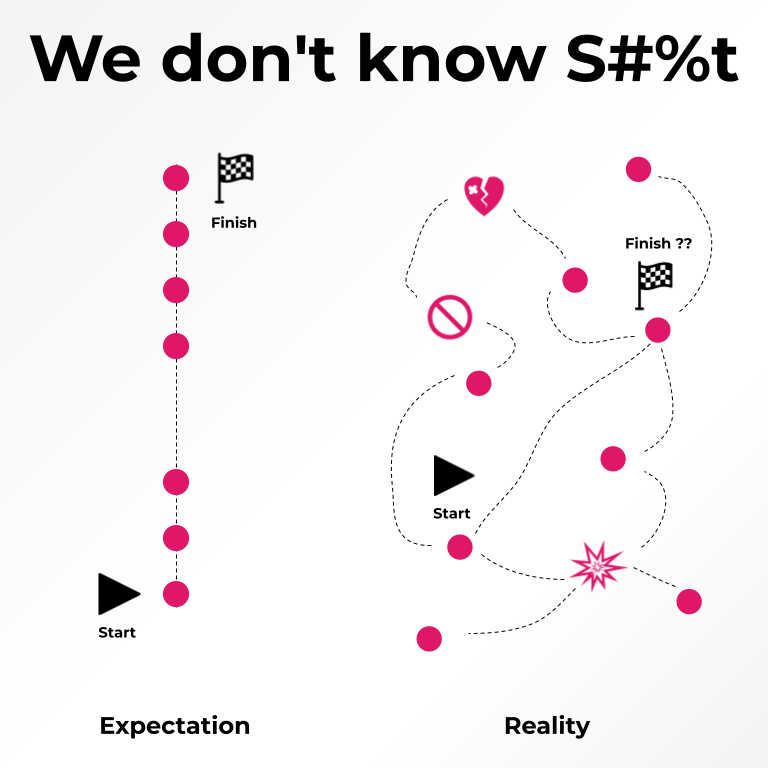

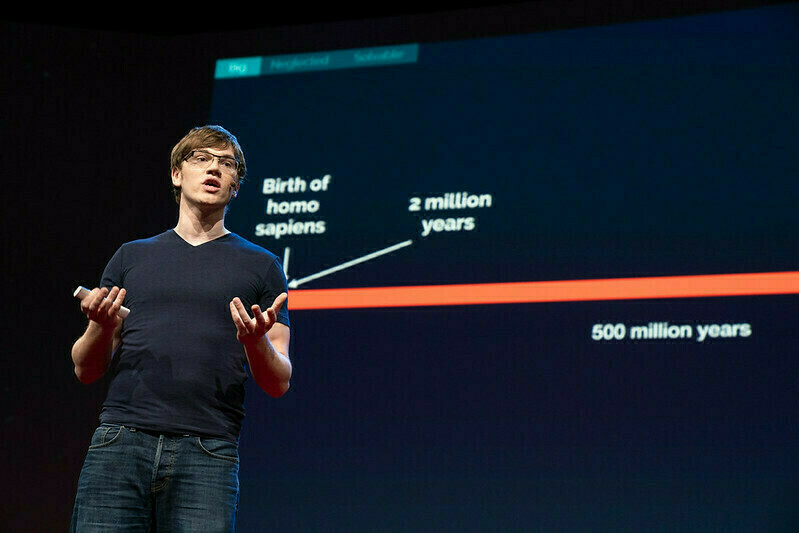

Cultivating (your) serendipity (surface)

I used to have a quotation on the wall as a History teacher that said “opportunity is missed by most people because it’s dressed in overalls and looks like work”. It’s been attributed to several people, but it’s the point that’s important: opportunities arrive in life, but you have to be looking for them.

Previously, I’ve called this (on my now defunct Discours.es blog) increasing your serendipity surface. In this post, Rob Miller breaks it down into three parts, which is interesting.

But if serendipity is the result of chance, does that mean it’s out of our control? Are we just at the whims of fate? Can we organise our lives to be more conducive to these serendipitous benefits?Source: Cultivating serendipity | Roblog, the blog of Rob MillerThree factors govern the supply of serendipity in our lives and the extent to which we notice and benefit from that serendipity:

Our supply of interesting opportunities is certainly within our control. Most straightforwardly, we could deliberately put ourselves into situations of extreme novelty: travelling, for example, or seeking out new people to meet, or reading unfamiliar materials. It’s also possible to introduce randomness into what might otherwise be routine, as the writer Robin Sloan has described in his own writing process. However you do it, putting yourself in front of a steady stream of new things – increasing your supply of novelty – will increase the chances of encountering unexpected benefits.

But we’re also surrounded at all times by unnoticed novelty, which links to the second factor: the extent to which we notice and respond positively to novel situations. There are countless ways to respond poorly to novelty. We can ignore it; we can notice it but greet it with indifference; we can fear it; we can attack it, as we might if it runs counter to our existing beliefs. All of these responses ensure the snuffing out of serendipity. The only response that allows for serendipity is improvisation: embracing novelty and making it a part of what you do.

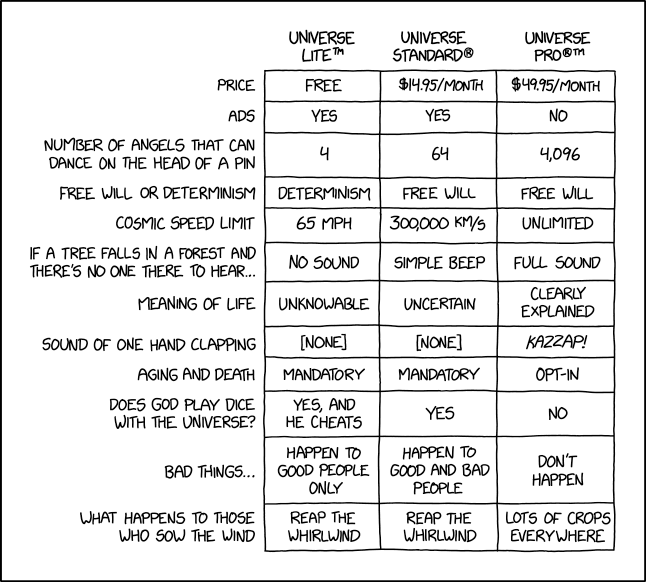

Life product tiers

A bit of fun from xkcd, but with some underlying truth in terms of how people experience life almost as if it were different product tiers.

Source: xkcd: Universe Price Tiers

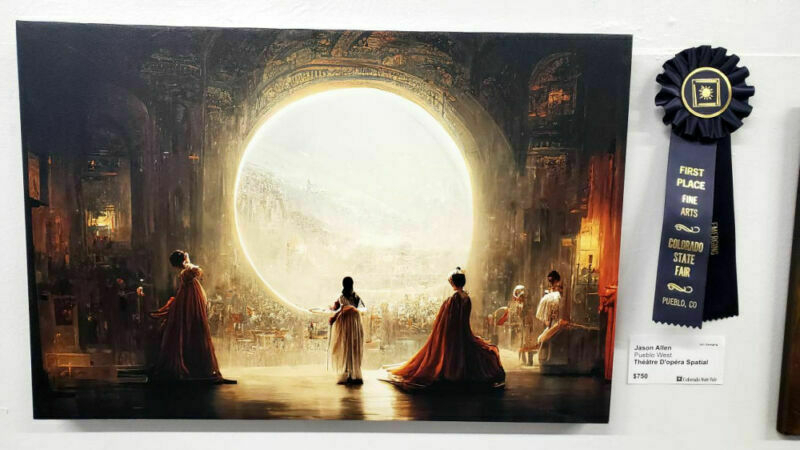

AI art is, well, still art

Art is a social thing. So it does not surprise me at all that people are upset that an AI-generated artwork won a competition.

However, after spending some time today (and in previous weeks) messing about with Midjourney and DALL-E 2 there’s a real talent to ‘prompt-crafting’. You can create amazing things, but not just by whacking in a bunch of words. Unless you’re very lucky.

Perhaps a ‘competition’ isn’t the best way to show off art. And perhaps selling individual works isn’t the best way to fund it?

A synthetic media artist named Jason Allen entered AI-generated artwork into the Colorado State Fair fine arts competition and announced last week that he won first place in the Digital Arts/Digitally Manipulated Photography category...Allen used Midjourney—a commercial image synthesis model available through a Discord server—to create a series of three images. He then upscaled them, printed them on canvas, and submitted them to the competition in early August. To his delight, one of the images (titled Théåtre D’opéra Spatial) captured the top prize, and he posted about his victory on the Midjourney Discord server on Friday.

Source: AI wins state fair art contest, annoys humans | Ars Technica

Learning through pathways

This is an interesting post that uses Google Maps as a metaphor for learning. In other words, get from where you are, to where you need to be, using an optimal route.

The author did some research, built pathways based on the findings, and presented them back to users. Who didn’t like them.

A similar approach was used in the Mozilla Discover project around Open Badges which is written up on Badge Wiki. The difference there, I guess, was that people were able to recognise specific inflection points that had meaning for them, and ascribe badges.

My opinion would be that people learn in different ways because of the context they bring to the table. You can rely on certain things to inspire most people, for example, or other things to resonate with some people. But there’s always a bit of experimentation to learning. It’s more like improvisational jazz than a symphony!

So, we do learn through pathways, but those pathways only have certain parts of the journey in common. To use another metaphor, it’s a bit like sharing a bus journey with other passengers for several stops, before getting on another bus (or hitch-hiking, or taking a taxi, or…)

I wanted to check the assumptions I had regarding the generation of paths for the Learning Map. So I scheduled interviews with instructors of these schools who were themselves also famous musicians. Their assumption was that I was interviewing them to create a story about their lives, but I was actually doing something far more interesting, I was deeply listening to the story of what and how they learned, and to the chronological order of their learning journey.More on this in this blog post about the session we ran at The Badge Summit on designing for recognition. Be sure to click through to the accompanying slide deck and the constellation model approach in slides 16 and 24!I asked them to describe their musical career, I let them know I wanted to create a timeline of their story, to start at the very beginning, and then to take me step by step through to their successes of today. Then I sat back and started to take notes:

Their first experience with music may have been with their mom who played the guitar, a lead singer they had a crush on, or a drum kit they got as a 5-year-old. They learned some key lessons and their journey kicked off. Over time, they may have learned to sing in Church, or worked in a recording studio. Some went to school, where they were introduced to new ideas from their peers, started a band, or trained underneath a mentor. Many went in completely different directions, they first become a chef, worked on a boat, or started bartending, each experience taught them skills they would later apply to their music. As they shared their experiences, I took notes, not about the events, the characters, or places, but only on the things they learned and when. I was mapping out their learning journeys, step by step, from their first experiences to their current work. I made an effort to cut through the superficial, and get to the heart of the lessons learned, this required the musician to deeply introspect, and was a fascinating experience on its own.

Several weeks later, after they had forgotten about the interviews and I had time to map each story out, I presented it back to them. But not as a story of their lives, instead, as a course, I wanted to run by them and get their professional opinion on. “What do you think of this course” “Do you think this is a good structure for a course?” I asked. They did not know this course was modeled after their own stories, they did not have any reason to tie this course back to the interviews conducted some months back and their responses were resounding: “This is a terribly designed course!” “How could you even think of wasting my time with this”, “Don’t you know that you need to understand X before you learn Y”…

Personal, portable heating solutions

I read this article when it was published on Low-tech Magazine earlier this year. Given the cost of living crisis is being exacerbated by gas prices this winter, Team Belshaw will be using hot water bottles as personal, portable heating solutions!

A hot water bottle is a sealable container filled with hot water, often enclosed in a textile cover, which is directly placed against a part of the body for thermal comfort. The hot water bottle is still a common household item in some places – such as the UK and Japan – but it is largely forgotten or disregarded in most of the industrialised world. If people know of it, they usually associate it with pain relief rather than thermal comfort, or they consider its use an outdated practice for the poor and the elderly.Source: The Revenge of the Hot Water Bottle | Low-tech Magazine[…]

Hot water bottles can be combined with a blanket, which further increases thermal comfort. If I put a blanket over the lower part of my body when seated at my desk, it traps the heat from the bottles and keeps them warm for longer. Even better is a blanket with a hole in the middle to stick your head through – a basic poncho – or a blanket with sleeves. If it’s large enough, it creates a tent-like structure that puts your whole body in the warm microclimate created by the water bottles. Draping long clothes over a personal heat source was a common comfort strategy in earlier times.

Potentially the cheapest way of generating clean energy?

I’m sharing this as an potentially-optimistic vision of another way of creating a lot of energy for the world. As the article states, this particular version might not be it, but sea waves contain a lot of energy…

Solar electricity generation is proliferating globally and becoming a key pillar of the decarbonization era. Lunar energy is taking a lot longer; tidal and wave energy is tantalizingly easy to see; step into the surf in high wave conditions and it's obvious there's an enormous amount of power in the ocean, just waiting to be tapped. But it's also an incredibly harsh and punishing environment, and we're yet to see tidal or wave energy harnessed on a mass scale.Source: Wave-riding generators promise the cheapest clean energy ever | New AtlasThat doesn’t mean people aren’t trying – we’ve seen many tidal energy ideas and projects over the years, and just as many dedicated to pulling in wave energy for use on land. There are a lot of prototypes and small-scale commercial installations either running or under construction, and the sector remains optimistic that it’ll make a significant clean energy contribution in years to come.

[…]

SWEL claims “one single Waveline Magnet will be rated at over 100 MW in energetic environments,” and the inventor and CEO, Adam Zakheos, is quoted in a press release as saying “… we can show how a commercial sized device using our technology will achieve a Levelized Cost of Energy (LCoE) less than 1c€(US$0.01)/kWhr, crushing today’s wave energy industry reference value of 85c€ (US$0.84)/kWh …”

[…]

[T]hese kinds of promises are where these yellow sea monsters start smelling a tad fishy to us. Despite many years of wave tank testing, SWEL says it’s still putting the results together, with “performance & scale-up projections, numerical and techno-financial modeling, feasibility studies and technology performance level” information yet to be released.

[…]

If SWEL delivers on its promises, well, you’re looking at nothing short of a clean energy revolution – one it’s increasingly obvious that the planet desperately needs, even if it comes in the form of yet more plastic floating in the ocean. But with investors lining up to throw money at green energy moonshots, the space has no shortage of bad-faith operators, wishful thinking and inflated expectations. And if SWEL’s many tests had generated the kinds of results that extrapolate to some of the world’s cheapest and cleanest energy, well, we’d expect to see a little more progress, some Gates-level investment flowing in, and more than an apparent sub-10 head count driving this thing along.

Population ethics

Will MacAskill is an Oxford philosopher. He’s an influential member of the Effective Altruism movement and has a view of the world he calls ‘longtermism’. I don’t know him, and I haven’t read his book, but I have done some ethics as part of my Philosophy degree.

As a parent, I find this review of his most recent book pretty shocking. I’m willing to consider most ideas but utilitarianism is the kind of thing which is super-attractive as a first-year Philosophy student but which… you grow out of?

The review goes more into depth than I can here, but human beings are not cold, calculating machines. We’re emotional people. We’re parents. And all I can say is that, well, my worldview changed a lot after I became a father.

Oxford philosophers William MacAskill and Toby Ord, both affiliated with the university’s Future of Humanity Institute, coined the word “longtermism” five years ago. Their outlook draws on utilitarian thinking about morality. According to utilitarianism—a moral theory developed by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century—we are morally required to maximize expected aggregate well-being, adding points for every moment of happiness, subtracting points for suffering, and discounting for probability. When you do this, you find that tiny chances of extinction swamp the moral mathematics. If you could save a million lives today or shave 0.0001 percent off the probability of premature human extinction—a one in a million chance of saving at least 8 trillion lives—you should do the latter, allowing a million people to die.Source: The New Moral Mathematics | Boston ReviewNow, as many have noted since its origin, utilitarianism is a radically counterintuitive moral view. It tells us that we cannot give more weight to our own interests or the interests of those we love than the interests of perfect strangers. We must sacrifice everything for the greater good. Worse, it tells us that we should do so by any effective means: if we can shave 0.0001 percent off the probability of human extinction by killing a million people, we should—so long as there are no other adverse effects.

[…]

MacAskill spends a lot of time and effort asking how to benefit future people. What I’ll come back to is the moral question whether they matter in the way he thinks they do, and why. As it turns out, MacAskill’s moral revolution rests on contentious, counterintuitive claims in “population ethics.”

[…]

[W]hat is most alarming in his approach is how little he is alarmed. As of 2022, the ‘Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ set the Doomsday Clock, which measures our proximity to doom, at 100 seconds to midnight, the closest it’s ever been. According to a study commissioned by MacAskill, however, even in the worst-case scenario—a nuclear war that kills 99 percent of us—society would likely survive. The future trillions would be safe. The same goes for climate change. MacAskill is upbeat about our chances of surviving seven degrees of warming or worse: “even with fifteen degrees of warming,” he contends, “the heat would not pass lethal limits for crops in most regions.”

This is shocking in two ways. First, because it conflicts with credible claims one reads elsewhere. The last time the temperature was six degree higher than preindustrial levels was 251 million years ago, in the Permian-Triassic Extinction, the most devastating of the five great extinctions. Deserts reached almost to the Arctic and more than 90 percent of species were wiped out. According to environmental journalist Mark Lynas, who synthesized current research in ‘Our Final Warning: Six Degrees of Climate Emergency’ (2020), at six degrees of warming the oceans will become anoxic, killing most marine life, and they’ll begin to release methane hydrate, which is flammable at concentrations of five percent, creating a risk of roving firestorms. It’s not clear how we could survive this hell, let alone fifteen degrees.

Conversational affordances

I’m one of those people who has to try hard not to over-analyse everything. Therapy has helped a bit, but I still can’t help reflecting on conversations I’ve had with people outside my family.

Why did that conversation go so well? Why was another one boring? Did I talk too much?

That sort of thing.

Which is why I found this article about ‘conversational doorknobs’ and improvisational comedy fascinating.

For me, learning take-and-take suggested a solution not just to songs about Spiderman, but to a scientific mystery. I was in graduate school at the time, running studies aimed at answering the question, “Do conversations end when people want them to?” I watched a stupefying number of conversations unfold, some of them blooming into beautiful repartee (one pair of participants exchanged numbers afterward), others collapsing into awkward silences. Why did some conversations unfurl and others wilt? One answer, I realized, may be the clash of take-and-take vs. give-and-take.There’s people I interact with on a semi-regular basis for which I, like other people, am just a convenient person to talk at. It can be entertaining for a while, but can get a bit too much. Likewise, there are others where I feel like I have to do most of the talking, and that’s just tiring.Givers think that conversations unfold as a series of invitations; takers think conversations unfold as a series of declarations. When giver meets giver or taker meets taker, all is well. When giver meets taker, however, giver gives, taker takes, and giver gets resentful (“Why won’t he ask me a single question?”) while taker has a lovely time (“She must really think I’m interesting!”) or gets annoyed (“My job is so boring, why does she keep asking me about it?”).

It’s easy to assume that givers are virtuous and takers are villainous, but that’s giver propaganda. Conversations, like improv scenes, start to sink if they sit still. Takers can paddle for both sides, relieving their partners of the duty to generate the next thing. It’s easy to remember how lonely it feels when a taker refuses to cede the spotlight to you, but easy to forget how lovely it feels when you don’t want the spotlight and a taker lets you recline on the mezzanine while they fill the stage. When you’re tired or shy or anxious or bored, there’s nothing better than hopping on the back of a conversational motorcycle, wrapping your arms around your partner’s waist, and holding on for dear life while they rocket you to somewhere new.

The best thing is when the two of your have a shared interest and you’re willing to take turns in asking questions and opening doorways. I’m not saying that I’m a particularly skilled conversationalist, but having attended a lot of events during my career, I’m better at it now than I used to be.

When done well, both giving and taking create what psychologists call affordances: features of the environment that allow you to do something. Physical affordances are things like stairs and handles and benches. Conversational affordances are things like digressions and confessions and bold claims that beg for a rejoinder. Talking to another person is like rock climbing, except you are my rock wall and I am yours. If you reach up, I can grab onto your hand, and we can both hoist ourselves skyward. Maybe that’s why a really good conversation feels a little bit like floating.Source: Good conversations have lots of doorknobs | Experimental HistoryWhat matters most, then, is not how much we give or take, but whether we offer and accept affordances. Takers can present big, graspable doorknobs (“I get kinda creeped out when couples treat their dogs like babies”) or not (“Let me tell you about the plot of the movie ‘Must Love Dogs’…”). Good taking makes the other side want to take too (“I know! My friends asked me to be the godparent to their Schnauzer, it’s so crazy” “What?? Was there a ceremony?”). Similarly, some questions have doorknobs (“Why do you think you and your brother turned out so different?”) and some don’t (“How many of your grandparents are still living?”). But even affordance-less giving can be met with affordance-ful taking (“I have one grandma still alive, and I think a lot about all this knowledge she has––how to raise a family, how to cope with tragedy, how to make chocolate zucchini bread––and how I feel anxious about learning from her while I still can”).

[…]

A few unfortunate psychological biases hold us back from creating these conversational doorknobs and from grabbing them when we see them. We think people want to hear about exciting stuff we did without them (“I went to Budapest!”) when they actually are happier talking about mundane stuff we did together (“Remember when we got stuck in traffic driving to DC?”). We overestimate the awkwardness of deep talk and so we stick to the boring, affordance-less shallows. Conversational affordances often require saying something at least a little bit intimate about yourself, so even the faintest fear of rejection on either side can prevent conversations from taking off. That’s why when psychologists want to jump-start friendship in the lab, they have participants answer a series of questions that require steadily escalating amounts of self-disclosure (you may have seen this as “The 36 Questions that Lead to Love”).