2022

Nesta's predictions for 2022

Nesta shares its ‘Future Signals’ for 2022, some predictions about how things might shake out this year. I’d draw your attention in particular to climate inactivism coupled with quantifying carbon, as well as health inequalities around the quality of sleep.

Under the microscope this year we look at topics that range from sleep as a new dimension of health inequality to where our food will be grown in future. We ask complicated questions too. Is carbon counting really a tool for behaviour change? How will Covid-related service closures impact families? Our Nesta authors don’t offer up easy answers, but this collection should help you to distinguish the signal from the noise in 2022 and beyond.Source: Future Signals – what we're watching for in 2022 | Nesta

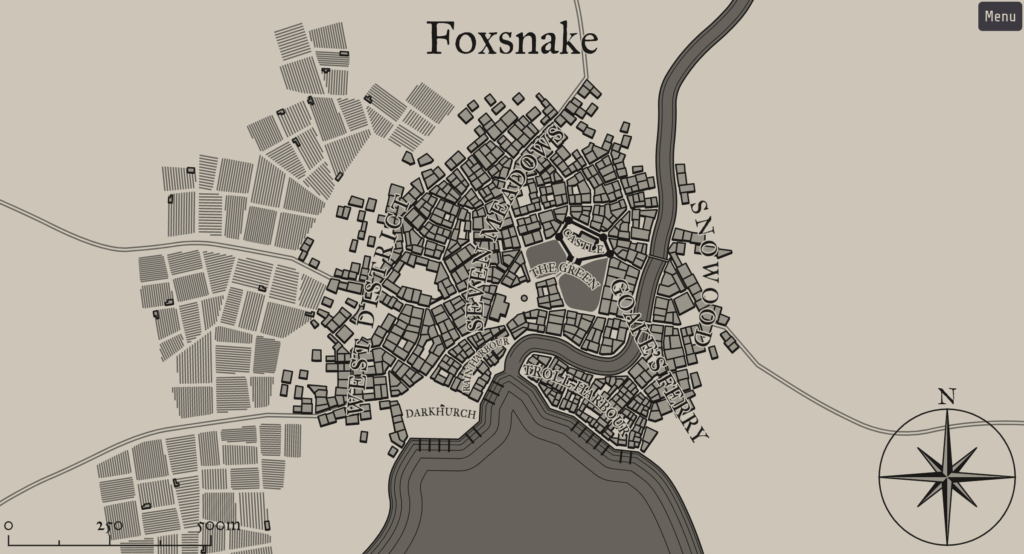

Medieval Fantasy City Generator

The history geek in me loves this so much. And the educator interested in digital literacies loves the fact that you have to manipulate the URL to generate different types of village / town / city!

Source: Medieval Fantasy City Generator

Blockchain and trusted third parties

As Cory Doctorow points out, merely putting something on a blockchain doesn’t make the data itself ‘trusted’ (or useful!)

In passing, it’s interesting that he cites Vinay Gupta in the piece, as Vinay is someone I’ve historically had a lot of time for. However, Mattereum (NFTs for physical assets) just… seems like a distraction from more important work he’s previously done?

In other words:Source: The Inevitability of Trusted Third Parties | Cory Doctorowif: problem + blockchain = problem - blockchain

then: blockchain = 0

The blockchain hasn’t added anything to the situation, except considerable cost (which could just as easily be spent on direct transfers to poor farmers, assuming you could find someone you trust to hand out the money) and complexity (which creates lots of opportunities for cheating).

On hobbies

This was linked to in the latest issue of Dense Discovery with the question of who amongst the readership has taken up a hobby recently?

As Anne Helen Petersen points out, it’s really hard to start a new hobby as an adult, not only for logistical reasons but because of the self-narrative that goes with it.

For me, the gulf between how good I am at something when starting it, and how good I want to be at a thing is often just too off-putting…

To me, that’s what I think a real hobby feels like. Not something you feel like you’re choosing, or scheduling — not a hassle, or something you resent or feel bad about when you don’t do it. Earlier this week, Katie Heaney wrote a piece in The Cut that speaks to what I think a lot of people feel when they think about their hobbies: she keeps trying to start one, but can’t make it stick. The truth is, it’s really really hard to start a hobby as an adult — it feels unnatural, or forced, or performative. We try to force ourselves into hobbies by buying things (see: Amanda Mull’s piece on the “trophies” of the new domesticity) but a Kitchen-Aid will not make you like cooking.Source: What a Hobby Feels Like | Anne Helen PetersenIt’s also hard when the messages about what you should be doing with your leisure time are so incredibly contradictory: you should devote yourself to self-care, but also spend more time on your children and partner; you should liberate yourself from the need to monetize your hobby but also have enough money to do the hobby in the first place. This “Smarter Living” piece in the NYT on what to do with a day off is emblematic of just how fucked up our leisure messaging has become: you should “embrace laziness,” “evaluate your career,” “have a family meal,” “fix your finances,” “do that one thing you’ve been putting off,” AND/OR “do nothing,” AND THEN tweet the author about what you did over the weekend!

Reducing offensive social media messages by intervening during content-creation

Six per cent isn’t a lot, but perhaps a number of approaches working together can help with this?

The proliferation of harmful and offensive content is a problem that many online platforms face today. One of the most common approaches for moderating offensive content online is via the identification and removal after it has been posted, increasingly assisted by machine learning algorithms. More recently, platforms have begun employing moderation approaches which seek to intervene prior to offensive content being posted. In this paper, we conduct an online randomized controlled experiment on Twitter to evaluate a new intervention that aims to encourage participants to reconsider their offensive content and, ultimately, seeks to reduce the amount of offensive content on the platform. The intervention prompts users who are about to post harmful content with an opportunity to pause and reconsider their Tweet. We find that users in our treatment prompted with this intervention posted 6% fewer offensive Tweets than non-prompted users in our control. This decrease in the creation of offensive content can be attributed not just to the deletion and revision of prompted Tweets -- we also observed a decrease in both the number of offensive Tweets that prompted users create in the future and the number of offensive replies to prompted Tweets. We conclude that interventions allowing users to reconsider their comments can be an effective mechanism for reducing offensive content online.Source: Reconsidering Tweets: Intervening During Tweet Creation Decreases Offensive Content | arXiv.org

The burnout epidemic

I work an average of about 25 hours per week and I’m tired at the end of it. I can’t even imagine how I coped in my twenties while teaching.

Textile mill workers in Manchester, England, or Lowell, Massachusetts, two centuries ago worked for longer hours than the typical British or American worker today, and they did so in dangerous conditions. They were exhausted, but they did not have the 21st-century psychological condition we call burnout, because they did not believe their work was the path to self-actualization. The ideal that motivates us to work to the point of burnout is the promise that if you work hard, you will live a good life: not just a life of material comfort, but a life of social dignity, moral character and spiritual purpose.Source: Your work is not your god: welcome to the age of the burnout epidemic | The Guardian[…]

This promise, however, is mostly false. It’s what the philosopher Plato called a “noble lie”, a myth that justifies the fundamental arrangement of society. Plato taught that if people didn’t believe the lie, then society would fall into chaos. And one particular noble lie gets us to believe in the value of hard work. We labor for our bosses’ profit, but convince ourselves we’re attaining the highest good. We hope the job will deliver on its promise, and hope gets us to put in the extra hours, take on the extra project and live with the lack of a raise or the recognition we need.

Check your perspective

A useful and illustrative story from Sheila Heen, author of Difficult Conversations: How To Discuss What Matters Most, about why it’s useful to understand other people’s context.

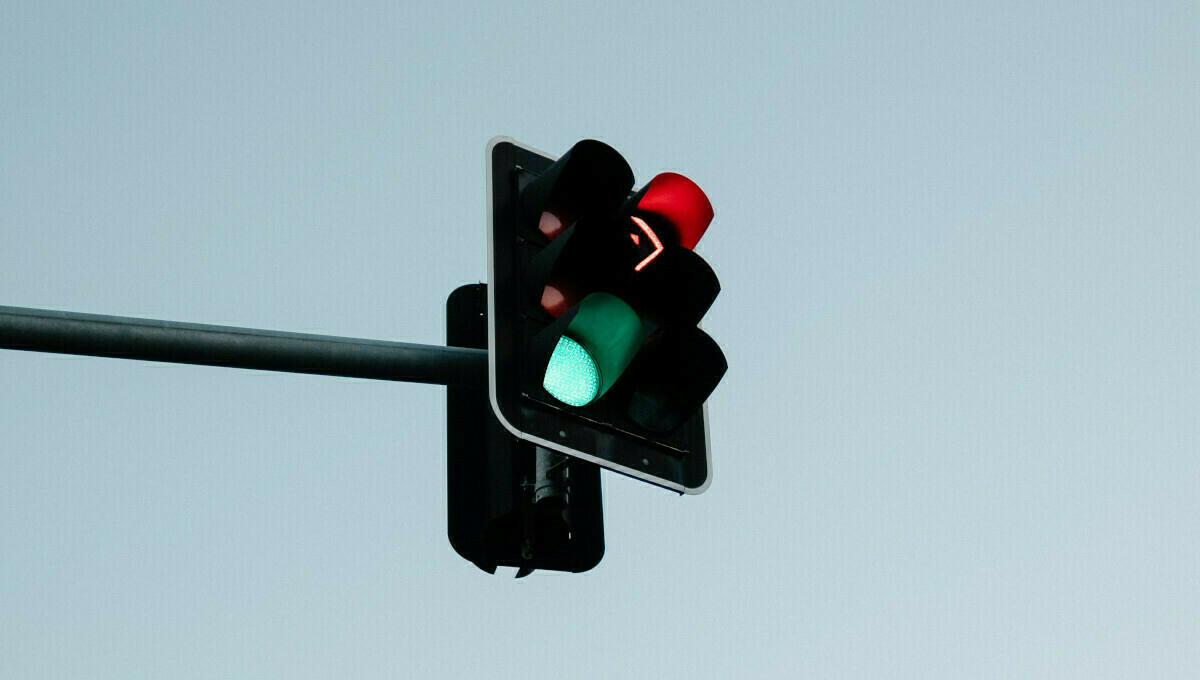

It reminds me, I sometimes tell this story about my eldest son. His name is Ben. He’s 22 now, but when he was about three, we were driving down the street. We stopped at a traffic light, and we were working on both colors and also traffic rules, because at the time we lived on kind of a busy street in Cambridge. So we’re stopped at the light. And I say, “Hey, Ben. What color is the light?” And he says, “It’s green.” I said, “Ben, we’re stopped at the light. What color is the light? Take a good look.” And he goes, “It’s green.” And when it turns, he says, “It’s red. Let’s go.”Source: Red Light Green Light | James SevedgeNow, the kid seemed bright in most other ways. So I just thought like, what is going on with him? My first hypothesis is maybe he’s color blind, which then that would be my husband’s fault. At least I thought at the time, it’s my husband’s fault. I’ve since been informed it would have been my fault.

So I started collecting data. I’m running a little scientific experiment of my own. So I start asking him to identify red and green in other contexts, and he gets it right every time. And yet every time we come to a traffic light, he’s still giving me opposite answers, because I get a little obsessed with this.

My second hypothesis, by the way, is that he is screwing with me, which I certainly had some data to support. This went on for about three weeks. It wasn’t until maybe three weeks later, and I think my mother-in-law was in town. So I was in the back seat sitting next to Ben, and we stopped at a traffic light. And I suddenly realized that from where he sits in his car seat, he usually can’t see the light in front of us, because the headrest is in the way or it’s above the level of the windshield, windscreen as they say in Europe. So he’s looking out the side window at the cross traffic light.

Now just think about the conversation from his point of view. He’s looking at the light, it’s green; I’m insisting that it’s red, and he’s like, you know, my mother seems right in most other ways, but she’s just wrong about this. The reason that that experience has stuck with me all these years is that it’s such a great illustration of the fact that where you sit determines what you see.

Productivity dysmorphia

This is a useful term for “the intersection of burnout, imposter syndrome, and anxiety”.

Say you manage a coffee shop. In one day, you placed all the orders with your vendors, cleaned all the machines, launched a new promotional push, scheduled your employees’ shifts for the following month, and responded to every review and email. In this hypothetical scenario, you did great! You got all those tasks done and were attentive to your employees’ needs for time off and fair schedules. So why do you still feel like you didn’t do enough and you’re failing? Productivity dysmorphia.Source: How to Overcome ‘Productivity Dysmorphia’ | Lifehacker[…]

Productivity dysmorphia can impact you outside of your job, too. Say you were aiming for a seven-day streak on your Peloton, but you were too tired or had too much work to do on that last day. You might feel like you are a failure for not working out that day, but that just isn’t true. You worked out the six days before that. Missing one goal doesn’t invalidate everything else you’ve done up until that point. We all get overwhelmed and overworked.

Try to reconsider what you think of as “productivity.” It’s productive to get all your work done, yes, and productive to work out or devote a certain amount of time every night to your side job or hobby. It’s also productive to rest. Relaxing and refreshing your mind and body will enable you to accomplish more in the near future without risking the dreaded burnout. Celebrate everything you do as a step toward productivity. Write down your rest periods, too. They count.

Twitter's decline into right-leaning hellsite

I quit Twitter at the start of December. Despite being an early adopter, joining in the same year as my son was born, 15 years later it’s gone from a force for good to a rage machine. I don’t want anything more to do with it.

The study looked at a sample of 4% of all Twitter users who had been exposed to the algorithm (46,470,596 unique users). It also included a control group of 11,617,373 users who had never received any automatically recommended tweets in their feeds.Source: Twitter’s algorithm favours the political right, a recent study finds | The Conversation[…]

The authors analysed the “algorithmic amplification” effect on tweets from 3,634 elected politicians from major political parties in seven countries with a large user base on Twitter: the US, Japan, the UK, France, Spain, Canada and Germany.

Algorithmic amplification refers to the extent to which a tweet is more likely to be seen on a regular Twitter feed (where the algorithm is operating) compared to a feed without automated recommendations.

[…]

The researchers found that in six out of the seven countries (Germany was the exception), the algorithm significantly favoured the amplification of tweets from politically right-leaning sources.

Overall, the amplification trend wasn’t significant among individual politicians from specific parties, but was when they were taken together as a group. The starkest contrasts were seen in Canada (the Liberals’ tweets were amplified 43%, versus those of the Conservatives at 167%) and the UK (Labour’s tweets were amplified 112%, while the Conservatives’ were amplified at 176%).

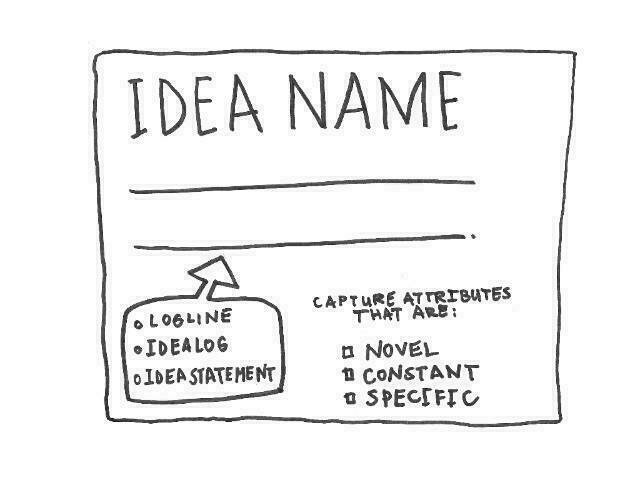

Explaining ideas

This comes at things from a branding/advertising perspective, but I appreciate the focus on clarity of language. After all, clarity of language is clarity of thought.

Ideas are thoughts but not all thoughts are “ideas.” Here’s an example of the use of the word “idea” in an agency setting: “I have an idea — let’s do something with augmented reality or Blockchain or make a special lens.” This isn’t wrong; it’s sloppy.Source: How to explain an idea: a mega post | Mark PollardIn the traditional industry sense, “idea” means a novel concept. But when it’s used as in this example, it masks the lack of an actual idea — like when someone dumps in the word “strategic” before they say something that’s not strategic. It ups the importance of what comes next. The problem: sometimes this works as a meeting tactic but does not lead to good or clear thinking.

Compare this thought with the use of the word “idea” as a novel concept: “I have an idea — I want to create a tool that runners can use to track how far they’ve run and then compete with each other by sharing their achievements via the Internet. They’ll track it via this technology in their shoe which will talk to their computer.”

BBC Archives and the changing of history

On the one hand, I’m glad that the BBC is ensuring that some of its archive material is a bit more in keeping with our (hopefully more enlightened) sensibilities.

However, on the other hand, why do this in secret?

“The sinister fact about literary censorship in England,” Orwell wrote back in 1945, “is that it is largely voluntary.” And so, indeed, it is. Over the weekend, the Daily Telegraph reported that “an anonymous Radio 4 Extra listener” had “discovered the BBC had been quietly editing repeats of shows over the past few years to be more in keeping with social mores.” To which the BBC said . . . well, yeah. In a statement addressing the charge, the institution confirmed that “on occasion we edit some episodes so they’re suitable for broadcast today, including removing racially offensive language and stereotypes from decades ago, as the vast majority of our audience would expect.” Thus, in the absence of law or regulation, has the British establishment begun to excise material it finds inappropriate by today’s lights.Source: BBC Censors Its Own Archives | National Review[…]

This raises a host of important questions — chief among which is: Why, if “the vast majority” of the BBC’s audience expects the organization to render its archives more “suitable,” has it been doing so in secret? Again: In the Internet age, changes made to source material tend to be iterative rather than additive. When the New York Times updates a story in its newspaper, one can plausibly obtain both copies. By contrast, when the New York Times updates a story on its website, the original page disappears. By its own admission, the BBC has been deleting entire sketches from comedy series that are 50, 60, or 70 years old, many of which can be heard only with the BBC’s permission. Are we simply to assume that the public supports this development? And, if so, are we permitted to wonder why the BBC was not open about it?

Private schools having charitable status is an absolute scam

I’ve always been against private schooling. I’m glad that others, even those who went to them themselves, are also seeing how bad they are for society.

I hate the new trend of British private schools opening branches abroad because the reason, it seems to me, is naked and unreflecting expansionism. It’s not spreading the original institution’s educational values because, as the Times investigation shows, they’re all too ready to drop those values in order to continue to trade. The desire for revenue obviously plays a part but, as the institutions don’t make profits, I don’t think personal financial rewards for the various executive headteachers or boards of governors are a huge factor. It’s less intelligent than that. It comes from an ill-considered capitalistic urge for growth, nothing more thought through than bigger is better.Source: Expansionist private schools need a lesson in morality | David Mitchell | The GuardianThis is the same reason McDonald’s opened a branch in Soviet Moscow, but that was fine because, as far as I know, McDonald’s has never applied for charitable status. What is astonishing is how, by conducting themselves in this way, private schools seem to have given up on making a meaningful argument to retain that status themselves. They’ve just stopped caring about the views of the likes of me. Is the right wing of the Conservative party now so completely dominant that the idea of keeping the sympathy of anyone on the left or in the centre feels like a waste of time?

Your attention was stolen

I still find it hard to trust Johann Hari’s writing, but this is more introspective and covers a subject that we all know is an issue: attention.

For me, despite being ‘verified’ on Twitter and having what used to be considered a decent number of followers, I’ve deactivated my account. I think it’s for the last time. I’m so much calmer when not using it.

I realised that to heal my attention, it was not enough simply to strip out distractions. That makes you feel good at first – but then it creates a vacuum where all the noise was. I realised I had to fill the vacuum. To do that, I started to think a lot about an area of psychology I had learned about years before – the science of flow states. Almost everyone reading this will have experienced a flow state at some point. It’s when you are doing something meaningful to you, and you really get into it, and time falls away, and your ego seems to vanish, and you find yourself focusing deeply and effortlessly. Flow is the deepest form of attention human beings can offer. But how do we get there?Source: Your attention didn’t collapse. It was stolen | The Guardian

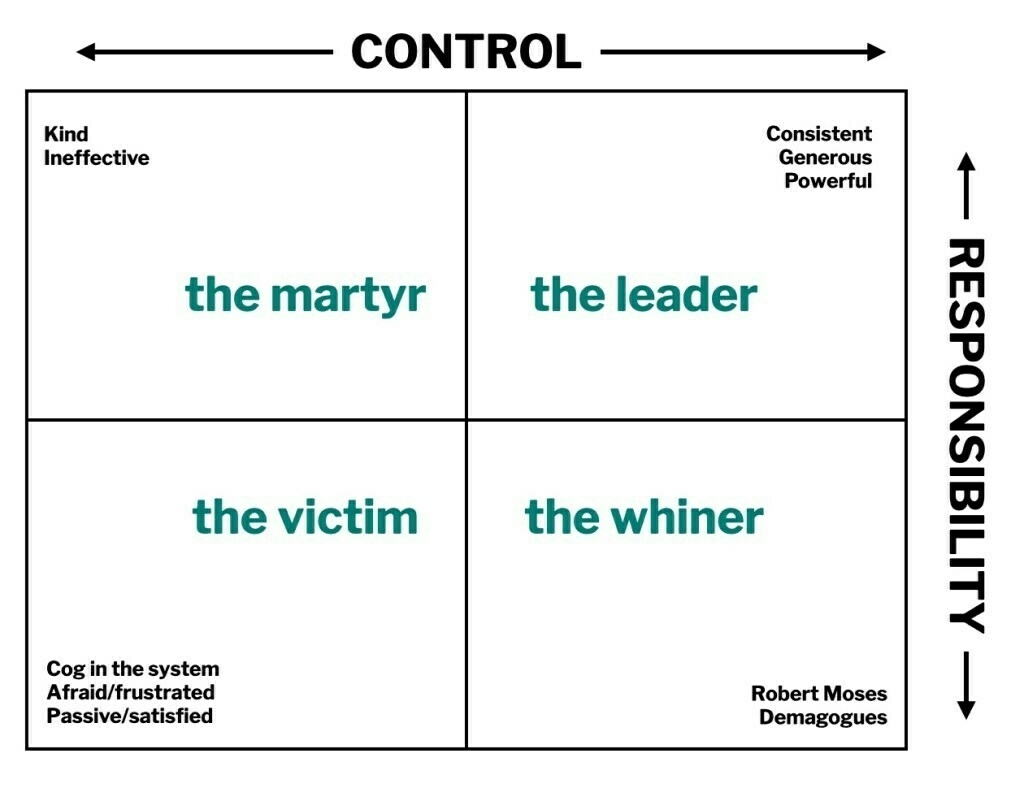

Control and responsibility

A massive over-simplification, but then that’s the point of 2x2 grids. Of course, everyone wants to think they’re in the top-right corner…

In many situations, we have the freedom to choose. We can choose a quadrant or we can choose not to participate. And if we’re lucky or care enough, we can choose who to vote for, who to work for and where we’re headed.Source: The control/responsibility matrix | Seth's Blog

Spatial Finance

Using real-time satellite imagery to ensure that people are building (or not-building) what they say they’re going to.

‘Spatial finance’ is the integration of geospatial data and analysis into financial theory and practice. Earth observation and remote sensing combined with machine learning have the potential to transform the availability of information in our financial system. It will allow financial markets to better measure and manage climate-related risks, as well as a vast range of other factors that affect risk and return in different asset classes.Source: Spatial Finance Initiative - Greening Finance and Investment

Health surveillance

It’s possible to be entirely in favour mass vaccination (as I am) while also concerned about the over-reach of states with our personal health data.

As this article discusses, based on a report from an German non-profit called AlgorithmWatch, such health surveillance is being normalised due to the requirements of responding to a global pandemic.

The idea that technology can be used to solve complex social issues, including public health, is not a new one. But the pandemic strongly influenced how technology is applied, with much of the push coming from public health policymaking and public perceptions, said the report.Source: Pandemic Exploited To Normalise Mass Surveillance? | The ASEAN PostThe report also highlighted the growing divide between people who fervently defend the schemes and those who staunchly oppose them - and how fear and misinformation have influenced both sides.

NFTs, financialisation, and crypto grifters

At over two hours long, I’m still only half-way through this video but I can already highly recommend it. There’s some technical language, as befits the nature of what’s discussed, but I really appreciate it going right back to the financial crisis to explain what’s going on.

[embed]www.youtube.com/watch

Source: The Problem With NFTs | YouTube

Tether and crypto price manipulation

You’d expect Jacobin to be against crypto, but this is the first level-headed explanation of the ‘Tether controversy’ I’ve seen.

There is no conceivable universe in which cryptocurrency exchanges should need an exponentially expanding supply of stablecoins to facilitate daily trading. The explosion in stablecoins and the suspicious timing of market buys outlined in the 2017 paper suggest — as a 2019 class-action lawsuit alleges — that iFinex, the parent company of Tether and Bitfinex, is printing tethers from thin air and using them to buy up Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies in order to create artificial scarcity and drive prices higher.Source: Cryptocurrency Is a Giant Ponzi Scheme | JacobinTether has effectively become the central bank of crypto. Like central banks, they ensure liquidity in the market and even engage in quantitative easing — the practice of central banks buying up financial assets in order to stimulate the economy and stabilize financial markets. The difference is that central banks, at least in theory, operate in the public good and try to maintain healthy levels of inflation that encourage capital investment. By comparison, private companies issuing stablecoins are indiscriminately inflating cryptocurrency prices so that they can be dumped on unsuspecting investors.

This renders cryptocurrency not merely a bad investment or speculative bubble but something more akin to a decentralized Ponzi scheme. New investors are being lured in under the pretense that speculation is driving prices when market manipulation is doing the heavy lifting.

This can’t go on forever. Unbacked stablecoins can and are being used to inflate the “spot price” — the latest trading price — of cryptocurrencies to levels totally disconnected from reality. But the electricity costs of running and securing blockchains is very real. If cryptocurrency markets cannot keep luring in enough new money to cover the growing costs of mining, the scheme will become unworkable and financially insolvent.

No one knows exactly how this would shake out, but we know that investors will never be able to realize the gains they have made on paper. The cryptocurrency market’s oft-touted $2 trillion market cap, calculated by multiplying existing coins by the latest spot price, is a meaningless figure. Nowhere near that much has actually been invested into cryptocurrencies, and nowhere near that much will ever come out of them.

Co-ops and DAOs

Handy article, especially for those deep in the ‘capitalist realism’ (or neoliberalism) that the author describes.

Although co-ops and DAOS are both collectively owned and co-determined organizational forms, there are some key differences. Primarily, cooperatives have one-member, one-vote governance. This means that people vote, not dollars. No single member of a cooperative can purchase more power than anyone else.Source: What Co-ops and DAOs Can Learn From Each OtherWhile it is possible for DAOs to emulate cooperative governance, it’s more common to observe the easier-to-implement governance pattern of one-token, one-vote, since verifying one’s personhood is still a nascent field in the world of blockchain.

[…]

From my experiences in the two spaces, I have noticed that DAOs tend to be better at enabling collective ownership at scale, even if their cultural understanding of the rights, responsibilities, and accountability associated with ownership is comparatively underdeveloped. And while cooperatives tend to be less successful in securing funding, they are also more likely, through their sober rejection of capitalist realism, to correctly address the root causes of inequity. Below, I’ll share some of the key takeaways I have gleaned about what DAOs and co-ops can learn from each other.

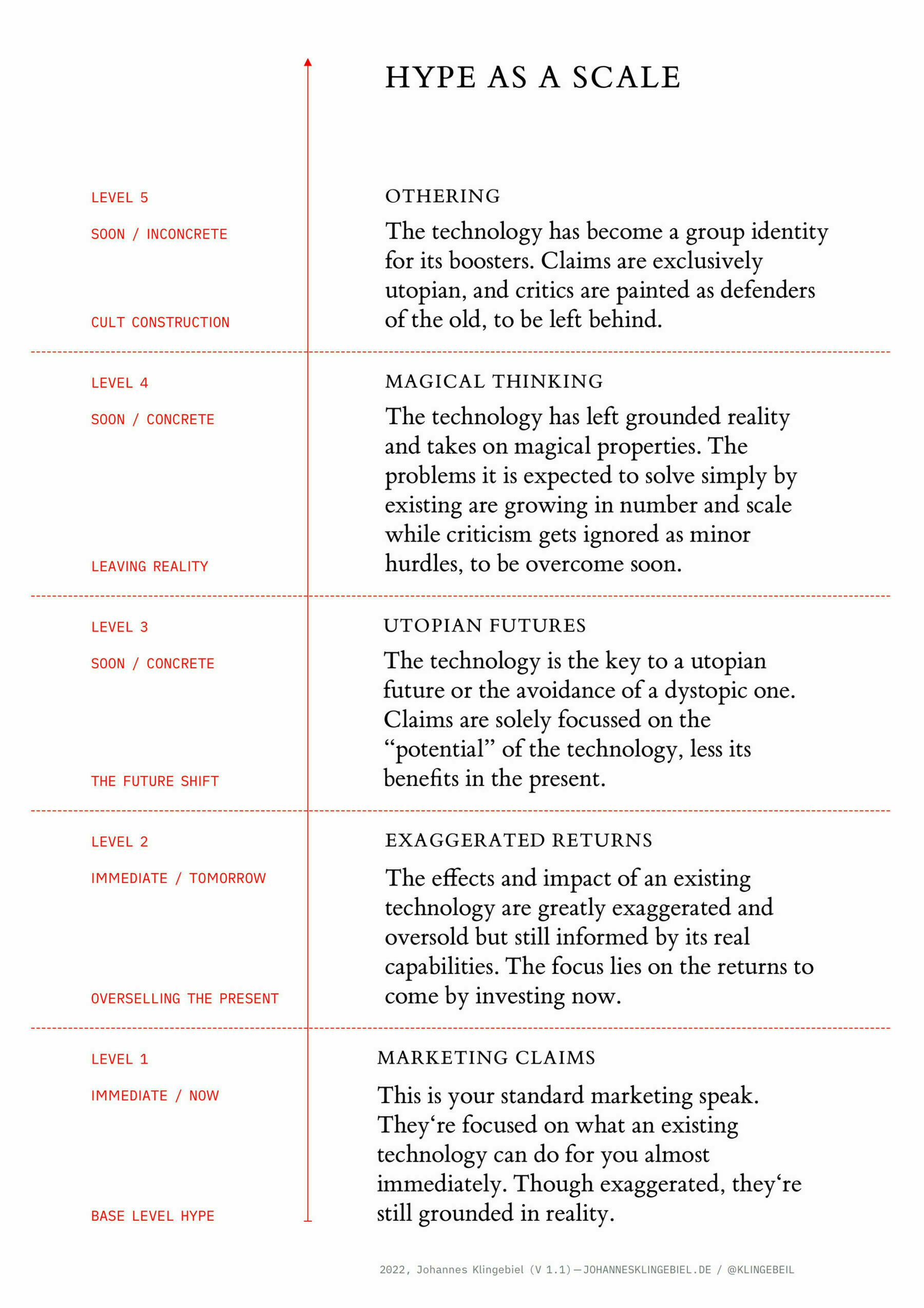

Hype levels

Handy. I do like typologies and scales.

Today‘s tech industry is obsessed with the big futures. The metaverses, the next internets — you name it. Hype is everywhere, oozing out of the headlines of news articles, growing like mold all over my LinkedIn feed, and blinking at me whenever I open my inbox.Source: The five Levels of Hype | Johannes KlingebielBut hype is not always the same; there are different forms and levels. I‘ve been trying my hand on a categorization based on my experience and my understanding of the phenomenon. This categorization is intended to help people better understand which form of hype they‘re confronted with.

[…]

Think of this scale as form of Richter scale to get a feel of how bad the hype is. A new technology doesn’t have to move through every single level but it most likely will at least reach level 3.