Everyone has a mob self and an individual self, in varying proportions

Digital mediation, decentralisation, and context collapse

Is social media 'real life'? A recent Op-Ed in The New York Times certainly things so:

An argument about Twitter — or any part of the internet — as “real life” is frequently an argument about what voices “matter” in our national conversation. Not just which arguments are in the bounds of acceptable public discourse, but also which ideas are considered as legitimate for mass adoption. It is a conversation about the politics of the possible. That conversation has many gatekeepers — politicians, the press, institutions of all kinds. And frequently they lack creativity.

Charlie Warzel (The New York Times)

I've certainly been a proponent over the years for the view that digital interactions are no less 'real' than analogue ones. Yes, you're reading a book when you do so on an e-reader. That's right, you're meeting someone when doing so over video conference. And correct, engaging in a Twitter thread counts as a conversation.

Now that everyone's interacting via digital devices during the pandemic, things that some parts of the population refused to count as 'normal' have at least been normalised. It's been great to see so much IRL mobilisation due to protests that started online, for example with the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag.

With this very welcome normalisation, however, I'm not sure there's a general understanding about how digital spaces mediate our interactions. Offline, our conversations are mediated by the context in which we find ourselves: we speak differently at home, on the street, and in the pub. Meanwhile, online, we experience context collapse as we take our smartphones everywhere.

We forget that we interact in algorithmically-curated environments that favour certain kinds of interactions over others. Sometimes these algorithms can be fairly blunt instruments, for example when 'Dominic Cummings' didn't trend on Twitter despite him being all over the news. Why? Because of anti-porn filters.

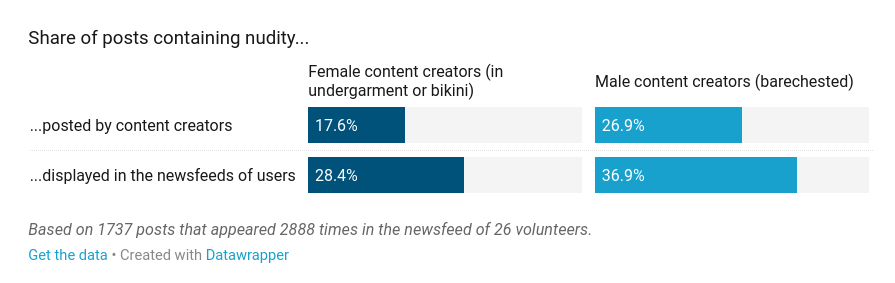

Other times, things are quite subtle. I've spoken on numerous occasions why I don't use Facebook products. Part of the reason for this is that I don't trust their privacy practices or algorithms. For example, a recent study showed that Instagram (which, of course, is owned by Facebook) actively encourages users to show some skin.

While Instagram claims that the newsfeed is organized according to what a given user “cares about most”, the company’s patent explains that it could actually be ranked according to what it thinks all users care about. Whether or not users see the pictures posted by the accounts they follow depends not only on their past behavior, but also on what Instagram believes is most engaging for other users of the platform.

Judith Duportail, Nicolas Kayser-Bril, Kira Schacht and Édouard Richard (Algorithm Watch)

I think I must have linked back to this post of mine from six years ago more than any other one I've written: Curate or Be Curated: Why Our Information Environment is Crucial to a Flourishing Democracy, Civil Society. To quote myself:

The problem with social networks as news platforms is that they are not neutral spaces. Perhaps the easiest way to get quickly to the nub of the issue is to ask how they are funded. The answer is clear and unequivocal: through advertising. The two biggest social networks, Twitter and Facebook (which also owns Instagram and WhatsApp), are effectively “services with shareholders.” Your interactions with other people, with media, and with adverts, are what provide shareholder value. Lest we forget, CEOs of publicly-listed companies have a legal obligation to provide shareholder value. In an advertising-fueled online world this means continually increasing the number of eyeballs looking at (and fingers clicking on) content.

Doug Belshaw (Connected learning Alliance)

Herein lies the difficulty. We can't rely on platforms backed by venture capital as they end up incentivised to do the wrong kinds of things. Equally, no-one is going to want to use a platform provided by a government.

This is why really do still believe that decentralisation is the answer here. Local moderation by people you know and/or trust that can happen on an individual or instance level. Algorithmic curation for the benefit of users which can be turned on or off by the user. Scaling both vertically and horizontally.

At the moment it's not the tech that's holding people back from such decentralisation but rather two things. The first is the mental model of decentralisation. I think that's easy to overcome, as back in 2007 people didn't really 'get' Twitter, etc. The second one is much more difficult, and is around the dopamine hit you get from posting something on social media and becoming a minor celebrity. Although it's possible to replicate this in decentralised environments, I'm not sure we'd necessarily want to?

Slightly modified quotation-as-title by D.H. Lawrence. Header image by Prateek Katyal