Feeling good (quote)

“You can’t get much done in life if you only work on the days when you feel good.”

(Jerry West)

Creativity as an ongoing experiment

It’s hard not to be inspired by the career of the Icelandic artist Björk. She really does seem to be single-minded and determined to express herself however she chooses.

This interview with her in The Creative Independent is from 2017 but was brought to my attention recently in their (excellent) newsletter. On being asked whether it’s OK to ever abandon a project, Björk replies:

If there isn’t the next step, and it doesn’t feel right, there will definitely be times where I don’t do it. But in my mind, I don’t look at it that way. It’s more like maybe it could happen in 10 years time. Maybe it could happen in 50 years time. That’s the next step. Or somebody else will take it, somebody else will look at it, and it will inspire them to write a poem. I look at it more like that, like it’s something that I don’t own.Creativity isn’t something that can be forced, she says:[…]

The minute your expectations harden or crystallize, you jinx it. I’m not saying I can always do this, but if I can stay more in the moment and be grateful for every step of the way, then because I’m not expecting anything, nothing was ever abandoned.

It’s like, the moments that I’ve gone to an island, and I’m supposed to write a whole album in a month, I could never, ever do that. I write one song a month, or two months, whatever happens… If there is a happy period or if there’s a sad period, or I have all the time in the world or no time in the world, it’s just something that’s kind of a bubbling underneath.Perhaps my favourite part of the interview, however, is where Björk says that she likes leaving things open for growth and new possibilities:

I like things when they’re not completely finished. I like it when albums come out. Maybe it’s got something to do with being in bands. We spent too long… There were at least one or two albums we made all the songs too perfect, and then we overcooked it in the studio, and then we go and play them live and they’re kind of dead. I think there’s something in me, like an instinct, that doesn’t want the final, cooked version on the album. I want to leave ends open or other versions, which is probably why I end up still having people do remixes, and when I play them live, I feel different and the songs can grow.Well worth reading in full, especially at this time of the year when everything seems full of new possibilities!

Source: The Creative Independent (via their newsletter)

Image by Maddie

Murmurations

Starlings where I live in Northumberland, England, also swarm like this, but not in so many numbers.

I love the way that we give interesting names to groups of animals English (e.g. a ‘murder’ of crows). There’s a whole list of them on Wikipedia.

Source: The Atlantic

Fanatics (quote)

“A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.”

(Winston Churchill)

The problem with Business schools

This article is from April 2018, but was brought to my attention via Harold Jarche’s excellent end-of-year roundup.

Business schools have huge influence, yet they are also widely regarded to be intellectually fraudulent places, fostering a culture of short-termism and greed. (There is a whole genre of jokes about what MBA – Master of Business Administration – really stands for: “Mediocre But Arrogant”, “Management by Accident”, “More Bad Advice”, “Master Bullshit Artist” and so on.) Critics of business schools come in many shapes and sizes: employers complain that graduates lack practical skills, conservative voices scorn the arriviste MBA, Europeans moan about Americanisation, radicals wail about the concentration of power in the hands of the running dogs of capital. Since 2008, many commentators have also suggested that business schools were complicit in producing the crash.When I finished my Ed.D. my Dad jokingly (but not-jokingly) said that I should next aim for an MBA. At the time, eight years ago, I didn't have the words to explain why I had no desire to do so. Now however, understanding a little bit more about economics, and a lot more about co-operatives, I can see that the default operating system of organisations is fundamentally flawed.

If we educate our graduates in the inevitability of tooth-and-claw capitalism, it is hardly surprising that we end up with justifications for massive salary payments to people who take huge risks with other people’s money. If we teach that there is nothing else below the bottom line, then ideas about sustainability, diversity, responsibility and so on become mere decoration. The message that management research and teaching often provides is that capitalism is inevitable, and that the financial and legal techniques for running capitalism are a form of science. This combination of ideology and technocracy is what has made the business school into such an effective, and dangerous, institution.I'm pretty sure that forming a co-op isn't on the curriculum of 99% of business schools. As Martin Parker, the author of this long article points out, after teaching in 'B-schools' for 20 years, ethical practices are covered almost reluctantly.

The problem is that business ethics and corporate social responsibility are subjects used as window dressing in the marketing of the business school, and as a fig leaf to cover the conscience of B-school deans – as if talking about ethics and responsibility were the same as doing something about it. They almost never systematically address the simple idea that since current social and economic relations produce the problems that ethics and corporate social responsibility courses treat as subjects to be studied, it is those social and economic relations that need to be changed.So my advice to someone who's thinking of doing an MBA? Don't bother. You're not going to be learning things that make the world a better place. Save your money and do something more worthwhile. If you want to study something useful, try researching different ways of structuring organistions — perhaps starting by using this page as a portal to a Wikipedia rabbithole?

Source: The Guardian (via Harold Jarche)

Working and leading remotely

As MoodleNet Lead, I’m part of a remote team. If you look at the org chart, I’m nominally the manager of the other three members of my team, but it doesn’t feel like that (at least to me). We’re all working on our areas of expertise and mine happens to be strategy, making sure the team’s OK, and interfacing with the rest of the organisation.

I’m always looking to get better at what I do, so a ‘crash course’ for managing remote teams by Andreas Klinger piqued my interest. There’s a lot of overlap with John O’Duinn’s book on distributed teams, especially in his emphasis of the difference between various types of remote working:

There is a bunch of different setups people call “remote teams”.Using these terms, the Open Badges team at Mozilla was 'Remote first', and when I joined Moodle I was a 'Remote employee', and now the MoodleNet team is 'Fully distributed'.When i speak of remote teams, i mean fully distributed teams and, if done right, remote-first teams. I consider all the other one’s hybrid setups.

- Satellite teams

- 2 or more teams are in different offices.

- Remote employees

- most of the team is in an office, but a few single employees are remote

- Fully distributed teams

- everybody is remote

- Remote first teams

- which are “basically” fully distributed

- but have a non-critical-mass office

- they focus on remote-friendly communication

Some things are easier when you work remotely, and some things are harder. One thing that’s definitely more difficult is running effective meetings:

Everybody loves meetings… right? But especially for remote teams, they are expensive, take effort and are – frankly – exhausting.I’m a big believer in working openly and documenting all the things. It saves hassle, it makes community contributions easier, and it builds trust. When everything’s out in the open, there’s nowhere to hide.If you are 5 people, remote team:

[...]

- You need to announce meetings upfront

- You need to take notes b/c not everyone needs to join

- Be on time

- Have a meeting agenda

- Make sure it’s not overtime

- Communicate further related information in slack

- etc

And this is not only about meetings. Meetings are just a straightforward example here. It’s true for any aspect of communication or teamwork. Remote teams need 5x the process.

Working remotely is difficult because you have to be emotionally mature to do it effectively. You’re dealing with people who aren’t physically co-present, meaning you have to over-communicate intention, provide empathy at a distance, and not over-react by reading something into a communication that wasn’t intended. This takes time and practice.

Ideally, as remote team lead, you want what Laura Thomson at Mozilla calls Minimum Viable Bureaucracy, meaning that you don’t just get your ducks in a row, you have self-organising ducks. As Klinger points out:

In remote teams, you need to set up in a way people can be as autonomously as they need. Autonomously doesn’t mean “left alone” it means “be able to run alone” (when needed).At the basis of remote work is trust. There’s no way I can see what my colleagues are doing 99% of the time while they’re working on the same project as me. The same goes for me. Some people talk about having to ‘earn’ trust, but once you’ve taken someone through the hiring process, it’s better just to give them your trust until they act in a way which makes you question it.Think of people as “fast decision maker units” and team communication as “slow input/output”. Both are needed to function efficiently, but you want to avoid the slow part when it’s not essential.

Source: Klinger.io (via Dense Discovery)

Rules for Online Sanity

It’s funny: we tell kids not to be mean to one another, and then immediately jump on social media to call people out and divide ourselves into various camps.

This list by Sean Blanda has been shared in several places, and rightly so. I’ve highlighted what I consider to be the top three.

Oh, and about "creating communities": why not support Thought Shrapnel via Patreon and comment on these posts along with people you already know have something in common?I’ve started thinking about what are the “new rules” for navigating the online world? If you could get everyone to agree (implicitly or explicitly) to a set of rules, what would they be? Below is an early attempt at an “Rules for Online Sanity” list. I’d love to hear what you think I missed.

- Reward your “enemies” when they agree with you, exhibit good behavior, or come around on an issue. Otherwise they have no incentive to ever meet you halfway.

- Accept it when people apologize. People should be allowed to work through ideas and opinions online. And that can result in some messy outcomes. Be forgiving.

- Sometimes people have differing opinions because they considered something you didn’t.

- Take a second.

- There's always more to the story. You probably don't know the full context of whatever you're reading or watching.

- If an online space makes more money the more time you spend on it, use sparingly.

- Judge people on their actions, not their words. Don’t get outraged over what people said. Get outraged at what they actually do.

- Try to give people the benefit of the doubt, be charitable in how you read people’s ideas.

- Don’t treat one bad actor as representative of whatever group or demographic they belong to.

- Create the kind of communities and ideas you want people to talk about.

- Sometimes, there are bad actors that don’t play by the rules. They should be shunned, castigated, and banned.

- You don’t always have the moral high ground. You are not always right.

- Block and mute quickly. Worry about the bubbles that creates later.

- There but for the grace of God go you.

Source: The Discourse (via Read Write Collect)

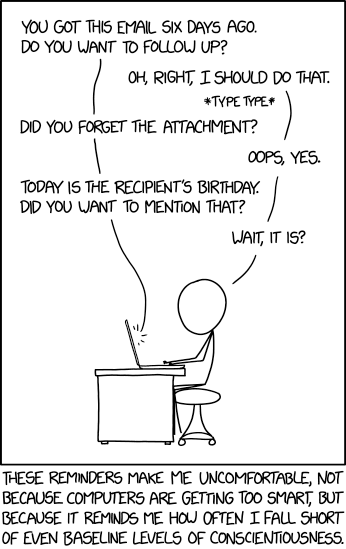

Baseline levels of conscientiousness

As I mentioned on New Years' Day, I’ve decided to trade some of my privacy for convenience, and am now using the Google Assistant on a regular basis. Unlike Randall Munroe, the author of xkcd, I have no compunction about outsourcing everything other than the Very Important Things That I’m Thinking About to other devices (and other people).

Source: xkcd

The endless Black Friday of the soul

This article by Ruth Whippman appears in the New York Times, so focuses on the US, but the main thrust is applicable on a global scale:

Apparently, 94% of the jobs created in the last decade are freelancer or contract positions. That's the trajectory we're on.When we think “gig economy,” we tend to picture an Uber driver or a TaskRabbit tasker rather than a lawyer or a doctor, but in reality, this scrappy economic model — grubbing around for work, all big dreams and bad health insurance — will soon catch up with the bulk of America’s middle class.

I don't think this is a neoliberal conspiracy, it's just the logic of capitalism seeping into every area of society. As we all jockey for position in the new-ish landscape of social media, everything becomes mediated by the market.Almost everyone I know now has some kind of hustle, whether job, hobby, or side or vanity project. Share my blog post, buy my book, click on my link, follow me on Instagram, visit my Etsy shop, donate to my Kickstarter, crowdfund my heart surgery. It’s as though we are all working in Walmart on an endless Black Friday of the soul.

[...]

Kudos to whichever neoliberal masterminds came up with this system. They sell this infinitely seductive torture to us as “flexible working” or “being the C.E.O. of You!” and we jump at it, salivating, because on its best days, the freelance life really can be all of that.

What I think’s missing from this piece, though, is a longer-term trend towards working less. We seem to be endlessly concerned about how the nature of work is changing rather than the huge opportunities for us to do more than waste away in bullshit jobs.

I’ve been advising anyone who’ll listen over the last few years that reducing the number of days you work has a greater impact on your happiness than earning more money. Once you reach a reasonable salary, there’s diminishing returns in any case.

Source: The New York Times (via Dense Discovery)

Blockchain bullshit

I’m sure blockchain technologies are going to revolutionise some sectors. But it’s not a consumer-facing solution; its applications are mainly back-office.

Of courses a lot of the hype around blockchain came through the link between it and cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

There’s a very real problem here, though. People with decision-making power read predictions by consultants and marketers. Then, without understanding what the tech really is or does, ensure it’s a requirement in rendering processes. This means that vendors either have to start offering that tech, or lie about the fact that they are able to do so.

We documented 43 blockchain use-cases through internet searches, most of which were described with glowing claims like “operational costs… reduced up to 90%,” or with the assurance of “accurate and secure data capture and storage.” We found a proliferation of press releases, white papers, and persuasively written articles. However, we found no documentation or evidence of the results blockchain was purported to have achieved in these claims. We also did not find lessons learned or practical insights, as are available for other technologies in development.There’s a simple lesson here: if you don’t understand something, don’t say it’s going to change the world.We fared no better when we reached out directly to several blockchain firms, via email, phone, and in person. Not one was willing to share data on program results, MERL processes, or adaptive management for potential scale-up. Despite all the hype about how blockchain will bring unheralded transparency to processes and operations in low-trust environments, the industry is itself opaque. From this, we determined the lack of evidence supporting value claims of blockchain in the international development space is a critical gap for potential adopters.

Source: MERL Tech (via The Register)

Looking back and forward in tech

Looking back at 2018, Amber Thomas commented that, for her, a few technologies became normalised over the course of the year:

- Phone payments

- Voice-controlled assistants

- Drones

- Facial recognition

- Fingerprints

However, December is always an important month for me. I come off social media, stop blogging, and turn another year older just before Christmas. It’s a good time to reflect and think about what’s gone before, and what comes next.

Sometimes, it’s possible to identify a particular stimulus to a change in thinking. For me, it was while I was watching Have I Got News For You and the panellists were shown a photo of a fashion designer who put a shoe in front of their face to avoid being recognisable. Paul Merton asked, “doesn’t he have a passport?”

Obvious, of course, but I’d recently been travelling and using the biometric features of my passport. I’ve also relented this year and use the fingerprint scanner to unlock my phone. I realised that the genie isn’t going back in the bottle here, and that everyone else was using my data — biometric or otherwise — so I might as well benefit, too.

Long story short, I’ve bought a Google Pixelbook and Lenovo Smart Display over the Christmas period which I’ll be using in 2019 to my life easier. I’m absolutely trading privacy for convenience, but it’s been a somewhat frustrating couple of years trying to use nothing but Open Source tools.

I’ll have more to say about all of this in due course, but it’s worth saying that I’m still committed to living and working openly. And, of course, I’m looking forward to continuing to work on MoodleNet.

Source: Fragments of Amber

See you in 2019!

Thought Shrapnel will be back next year. Until then, unless you’re a supporter, that’s it for 2018.

Thanks for reading, and have a good break.

Routine and ambition (quote)

“Routine, in an intelligent man, is a sign of ambition.”

(W.H. Auden)

Is the unbundling and rebundling of Higher Education actually a bad thing?

Until I received my doctorate and joined the Mozilla Foundation in 2012, I’d spent fully 27 years in formal education. Either as a student, a teacher, or a researcher, I was invested in the Way Things Currently Are®.

Over the past six years, I’ve come to realise that a lot of the scaremongering about education is exactly that — fears about what might happen, based on not a lot of evidence. Look around; there are lot of doom-mongers about.

It was surprising, therefore, to read a remarkably balanced article in EDUCAUSE Review. Laura Czerniewicz, Director of the Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching (CILT), at the University of Cape Town, looks at the current state of play around the ‘unbundling’ and ‘rebundling’ of Higher Education.

Very simply, I'm using the term unbundling to mean the process of disaggregating educational provision into its component parts, very often with external actors. And I'm using the term rebundling to mean the reaggregation of those parts into new components and models. Both are happening in different parts of college and university education, and in different parts of the degree path, in every dimension and aspect—creating an extraordinarily complicated environment in an educational sector that is already in a state of disequilibrium.Although it’s largely true that the increasing marketisation is a stimulus for the unbundling of Higher Education, I’m of the opinion that what we’re seeing has been accelerated primarily because of the internet. The end of capitalism wouldn’t necessarily remove the drive towards this unbundling and rebundling. In fact, I wonder what it would look like if it were solely non-profits, charities, and co-operatives doing this?Unbundling doesn’t simply happen. Aspects of the higher education experience disaggregate and fragment, and then they get re-created—rebundled—in different forms. And it’s the re-creating that is especially of interest.

Czerniewicz identifies seven main aspects of Higher Education that are being unbundled:

- Curriculum

- Resources

- Flexible pathways

- Academic expertise

- Opportunities

- Support

- Credentials

- Networks

- Graduateness (i.e. 'the status of being a graduate')

- Experience

- Mode (e.g. online, blended)

- Place

As Czerniewicz points out, there isn’t anything inherently wrong with unbundling and rebundling. It’s potentially a form of creative destruction, followed by some Hegelian synthesis.

But I'd like to conclude on a hopeful note. Unbundling and rebundling can be part of the solution and can offer opportunities for reasonable and affordable access and education for all. Unbundling and rebundling are opening spaces, relationships, and opportunities that did not exist even five years ago. These processes can be harnessed and utilized for the good. We need to critically engage with these issues to ensure that the new possibilities of provision for teaching and learning can be fully exploited for democratic ends for all.Goodness knows that, as a sector, Higher Education can do a much better job of the three main things I'd say we'd want of universities in 2018:

- Developing well-rounded citizens ready to participate fully in democratic society.

- Sending granular signals to the job market about the talents and competencies of individuals.

- Enabling extremely flexible provision for those in work, or who want to take different learning pathways.

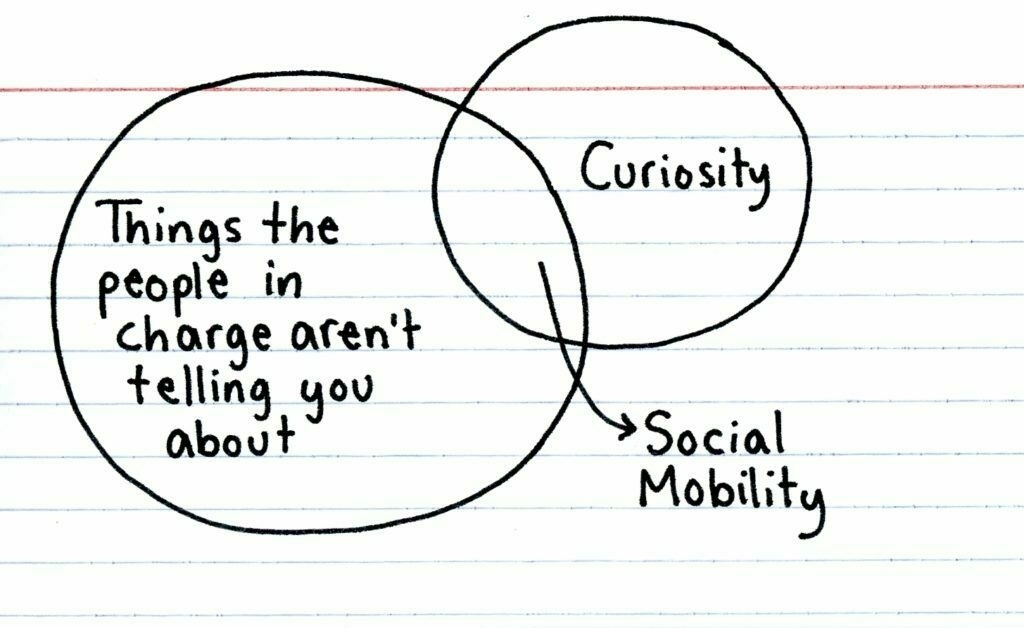

I think the main reason I’m interested in all of this is mainly through the lens of new forms of credentialing. Czerniewicz writes:

Certification is an equity issue. For most people, getting verifiable accreditation and certification right is at the heart of why they are invested in higher education. Credentials may prove to be the real equalizers in the world of work, but they do raise critical questions about the function and the reputation of the higher education institution. They also raise questions about value, stigma, and legitimacy. A key question is, how can new forms of credentials increase access both to formal education and to working opportunities?I agree. So the main reason I got involved in Open Badges was that I saw the inequity as a teacher. I want, by the time our eldest child reaches the age where he's got the choice to go to university (2025), to be able to make an informed choice not to go — and still be OK. Credentialing is an arms race that I've done alright at, but which I don't really want him to be involved in escalating.

So, to conclude, I’m actually all for the unbundling and rebundling of education. As Audrey Watters has commented many times before, it all depends who is doing the rebundling. Is it solely for a profit motive? Is it improving things for the individual? For society? Who gains? Who loses?

Ultimately, this isn’t something that be particularly ‘controlled’, only observed and critiqued. No-one is secretly controlling how this is playing out worldwide. That’s not to say, though, that we shouldn’t call out and resist the worst excesses (I’m looking at you, Facebook). There’s plenty of pedagogical process we can make as this all unfolds.

Source: Educause

Credentials and standardisation

Someone pinch me, because I must be dreaming. It’s 2018, right? So why are we still seeing this kind of article about Open Badges and digital credentials?

“We do have a little bit of a Wild West situation right now with alternative credentials,” said Alana Dunagan, a senior research fellow at the nonprofit Clayton Christensen Institute, which researches education innovation. The U.S. higher education system “doesn’t do a good job of separating the wheat from the chaff.”You'd think by now we'd realise that we have a huge opportunity to do something different here and not just replicate the existing system. Let's credential stuff that matters rather than some ridiculous notion of 'employability skills'. Open Badges and digital credentials shouldn't be just another stick to beat educational institutions.

Nor do they need to be ‘standardised’. Another person’s ‘wild west’ is another person’s landscape of huge opportunity. We not living in a world of 1950s career pathways.

“Everybody is scrambling to create microcredentials or badges,” Cheney said. “This has never been a precise marketplace, and we’re just speeding up that imprecision.”My eyes are rolling out of my head at this point. Thankfully, I’ve already written about misguided notions around ‘quality’ and ‘rigour’, as well thinking through in a bit more detail what earning a ‘credential’ actually means.Arizona State University, for example, is rapidly increasing the number of online courses in its continuing and professional education division, which confers both badges and certificates. According to staff, the division offers 200 courses and programs in a slew of categories, including art, history, education, health and law, and plans to provide more than 500 by next year.

Source: The Hechinger Report

Are we nearing the end of the Facebook era?

Betteridge’s law of headlines states that “any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.” So perhaps I should have rephrased the title of this post.

However, I did find this post by Gina Bianchini interesting about what people are using instead of Facebook:

The three most obvious alternatives people are turning to are:As ever, people will say that Facebook will never go away because the majority of people use it. But, as Bianchini points out, innovation happens at the edges, among the early adopters. Many of those have already moved on:

- Private Messaging Platforms. We’re already seeing people move conversations with their family and close friends to iMessage, Houseparty, Marco Polo, Telegram, Discord, and Signal for their most important relationships or interests.

- Vertical Social Networks and Subscription Content. Watch as time spent on The Athletic, NextDoor, Houzz, and other verticals goes up in the next year. People want to connect to content that matters to them, and the services that focus on a specific subject area will win their domain.

- Highly Curated, Professional-Led Podcasts, Email Newsletters, Events, and Membership Communities. The professionalization of creators and influencers will continue unabated. Emboldened by the fact that their followers are now willing to follow them to new places (and increasingly even pay for access), these emerging brands will look to own their engagement and relationships, not rent them from Facebook.

Growth halts on the edges, not the core. Facebook’s prominence is eroding as the sources of creativity and goodwill that gave it magic, substance, and cultural relevance are quietly moving on. The reality is that Facebook stopped giving creators a return on their time a long time ago.This all comes from a renewed interest in ‘quality’ time. I was particularly interested in the way Seth Godin recently talked about how the digital divide is being flipped. Bianchini concludes:[…]

Big brands will be the last to leave. Unlike creators and Group admins, big brands will stick with Facebook for as long as possible. Despite CPMs jumping 171% in one year, big brands have institutionalized Facebook ad buying and posting not only with budgets but with dedicated teams. They’re too invested to acknowledge the writing on the wall, despite objectively diminishing returns.

As more people become conscious of how we spend our time online, we will choose differently. We will seek to feel good about what we’re contributing and what we’re getting out of our time invested. There will emerge new safe, positive places governed not by algorithms and monolithic companies, but curated by real people who have a passion for inspiring and uplifting other human beings.It's really interesting to see this change happening. As she says, it's not 'inevitable', but cultural differences and personal values are as important in the digital world as in the physical.

Also, as we should always remember, Facebook the company owns WhatsApp and Instagram, so they’ll be find whatever. They’ve hedged their bets as any monopoly player would do.

Source: LinkedIn

Asking Google philosophical questions

Writing in The Guardian, philosopher Julian Baggini reflects on a recent survey which asked people what they wish Google was able to answer:

The top 25 questions mostly fall into four categories: conspiracies (Who shot JFK? Did Donald Trump rig the election?); desires for worldly success (Will I ever be rich? What will tomorrow’s winning lottery numbers be?); anxieties (Do people like me? Am I good in bed?); and curiosity about the ultimate questions (What is the meaning of life? Is there a God?).This is all hypothetical, of course, but I'm always amazed by what people type into search engines. It's as if there's some 'truth' in there, rather than just databases and algorithms. I suppose I can understand children asking voice assistants such as Alexa and Siri questions about the world, because they can't really know how the internet works.

What Baggini points out, though, is that what we type into search engines can reflect our deepest desires. That’s why they trawl the search history of suspected murderers, and why the Twitter account Theresa May Googling is so funny.

A Google search, however, cannot give us the two things we most need: time and other people. For our day-to-day problems, a sympathetic ear remains the most powerful device for providing relief, if not a cure. For the bigger puzzles of existence, there is no substitute for long reflection, with help from the great thinkers of history. Google can lead us directly to them, but only we can spend time in their company. Search results can help us only if they are the start, not the end, of our intellectual quest.Sadly, in the face of, let's face it, pretty amazing technological innovation over the last 25 years, we've forgotten what it is that makes us human: connections. Thankfully, some more progressive tech companies are beginning to realise the importance of the Humanities — including Philosophy.

Source: The Guardian

Gamifying Wikipedia for new editors

Hands up who uses Wikipedia? OK, keep your hands up if you edit it too? Ah.

Not only does Wikipedia need our financial donations to keep running, it also needs our time. To encourage people to edit it, the Wikimedia Foundation have created an ‘adventure’ by way of orientation.

It’s split into seven stages:

- Say Hello to the World

- An Invitation to Earth

- Small Changes, Big Impact

- The Neutral Point of View

- The Veil of Verifiability

- The Civility Code

- Looking Good Together

Source: Wikipedia (via Scott Leslie)

Daily routine (quote)

“The secret to your success is found in your daily routine.”

(John C. Maxwell)