Opting in and out of algorithms

It's now over seven years since I submitted my doctoral thesis on digital literacies. Since then, almost the entire time my daughter has been alive, the world has changed a lot.

Writing in The Conversation, Anjana Susarla explains her view that digital literacy goes well beyond functional skills:

In my view, the new digital literacy is not using a computer or being on the internet, but understanding and evaluating the consequences of an always-plugged-in lifestyle. This lifestyle has a meaningful impact on how people interact with others; on their ability to pay attention to new information; and on the complexity of their decision-making processes.

Digital literacies are plural, context-dependent and always evolving. Right now, I think Susarla is absolutely correct to be focusing on algorithms and the way they interact with society. Ben Williamson is definitely someone to follow and read up on in that regard.

Over the past few years I've been trying (both directly and indirectly) to educate people about the impact of algorithms on everything from fake news to privacy. It's one of the reasons I don't use Facebook, for example, and go out of my way to explain to others why they shouldn't either:

A study of Facebook usage found that when participants were made aware of Facebook’s algorithm for curating news feeds, about 83% of participants modified their behavior to try to take advantage of the algorithm, while around 10% decreased their usage of Facebook.

[...]However, a vast majority of platforms do not provide either such flexibility to their end users or the right to choose how the algorithm uses their preferences in curating their news feed or in recommending them content. If there are options, users may not know about them. About 74% of Facebook’s users said in a survey that they were not aware of how the platform characterizes their personal interests.

Although I'm still not going to join Facebook, one reason I'm a little more chilled out about algorithms and privacy these days is because of the GDPR. If it's regulated effectively (as I think it will be) then it should really keep Big Tech in check:

As part of the recently approved General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union, people have “a right to explanation” of the criteria that algorithms use in their decisions. This legislation treats the process of algorithmic decision-making like a recipe book. The thinking goes that if you understand the recipe, you can understand how the algorithm affects your life.

[...]But transparency is not a panacea. Even when an algorithm’s overall process is sketched out, the details may still be too complex for users to comprehend. Transparency will help only users who are sophisticated enough to grasp the intricacies of algorithms.

I agree that it's not enough to just tell people that they're being tracked without them being able to do something about it. That leads to technological defeatism. We need a balance between simple, easy-to-use tools that enable user privacy and security. These aren't going to come through tech industry self-regulation, but through regulatory frameworks like GDPR.

Source: The Conversation

Also check out:

- Platforms Want Centralized Censorship. That Should Scare You (WIRED) — "The risk of overbroad censorship from automated filtering tools has been clear since the earliest days of the internet"

- What to do if your boss is an algorithm (BBC Ideas) — "Digital sociologist Karen Gregory on how to cope when your boss isn't actually human."

- Optimize Algorithms to Support Kids Online, Not Exploit Them (WIRED) — "Children are exposed to risks at churches, schools, malls, parks, and anywhere adults and children interact. Even when harms and abuses happen, we don’t talk about shutting down parks and churches, and we don’t exclude young people from these intergenerational spaces."

Let's not force children to define their future selves through the lens of 'work'

I discovered the work of Adam Grant through Jocelyn K. Glei's excellent Hurry Slowly podcast. He has his own, equally excellent podcast, called WorkLife which he creates with the assistance of TED.

Writing in The New York Times as a workplace psychologist, Grant notes just how problematic the question "what do you want to be when you grow up?" actually is:

When I was a kid, I dreaded the question. I never had a good answer. Adults always seemed terribly disappointed that I wasn’t dreaming of becoming something grand or heroic, like a filmmaker or an astronaut.

Let's think: from what I can remember, I wanted to be a journalist, and then an RAF pilot. Am I unhappy that I'm neither of these things? No.

Perhaps it's because a job is more tangible than an attitude or approach to life, but not once can I remember being asked what kind of person I wanted to be. It was always "what do you want to be when you grow up?", and the insinuation was that the answer was job-related.

My first beef with the question is that it forces kids to define themselves in terms of work. When you’re asked what you want to be when you grow up, it’s not socially acceptable to say, “A father,” or, “A mother,” let alone, “A person of integrity.”

[...]

The second problem is the implication that there is one calling out there for everyone. Although having a calling can be a source of joy, research shows that searching for one leaves students feeling lost and confused.

Another fantastic podcast episode I listened to recently was Tim Ferriss' interview of Caterina Fake. She's had an immensely successful career, yet her key messages during that conversation were around embracing your 'shadow' (i.e. melancholy, etc.) and ensuring that you have a rich inner life.

While the question beloved of grandparents around the world seems innocuous enough, these things have material effects on people's lives. Children are eager to please, and internalise other people's expectations.

I’m all for encouraging youngsters to aim high and dream big. But take it from someone who studies work for a living: those aspirations should be bigger than work. Asking kids what they want to be leads them to claim a career identity they might never want to earn. Instead, invite them to think about what kind of person they want to be — and about all the different things they might want to do.

The jobs I've had over the last decade didn't really exist when I was a child, so it would have been impossible to point to them. Let's encourage children to think of the ways they can think and act to change the world for the better - not how they're going to pay the bills to enable themselves to do so.

Source: The New York Times

Also check out:

- The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education (Highline) — "As our most trusted universities continue to privatize large swaths of their academic programs, their fundamental nature will be changed in ways that are hard to reverse. The race for profits will grow more heated, and the social goal of higher education will seem even more like an abstraction."

- Social Peacocking and the Shadow (Caterina Fake) — "Social peacocking is life on the internet without the shadow. It is an incomplete representation of a life, a half of a person, a fraction of the wholeness of a human being."

- Why and How Capitalism needs to be reformed (Economic Principles) — "The problem is that capitalists typically don’t know how to divide the pie well and socialists typically don’t know how to grow it well."

How to subscribe to Thought Shrapnel Daily

From Monday I'll be publishing Thought Shrapnel Daily five times per week. Patreon supporters get immediate and exclusive access to those updates for a one-week period after publication. They'll then be available to everyone on the open web.

Here's how you can be informed when Thought Shrapnel Daily is published:

- Email (supporters will be auto-subscribed)

- Push notification

- RSS

Alternatively, you can just check thoughtshrapnel.com every day after 12pm UTC! Note that you'll need to be logged-in to Patreon to access Thought Shrapnel Daily when it's first published.

A visit to the Tate Modern by Bryan Mathers is licenced under CC-BY-ND

Giving up Thought Shrapnel for Lent

Recently, the Slack-based book club I started has been reading Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism. His writing made me consider giving up my smartphone for Lent as a form of ‘digital detox’. However, when I sat with the idea a while, another one replaced it: give up Thought Shrapnel for Lent instead!

Why?

Putting together Thought Shrapnel is something that I certainly enjoy doing, but something that takes me away from other things, once you’ve factored in all of the reading, writing, and curating involved in putting out several weekly posts and a newsletter.

I’ve also got a lot of other things right now, with MoodleNet getting closer to a beta launch, and recently becoming a Scout Leader.

So I’m pressing pause for Lent, and have already notified the awesome people who support Thought Shrapnel via Patreon. It will be back after Easter!

Giving up Thought Shrapnel for Lent

Recently, the Slack-based book club I started has been reading Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism. His writing made me consider giving up my smartphone for Lent as a form of ‘digital detox’. However, when I sat with the idea a while, another one replaced it: give up Thought Shrapnel for Lent instead!

Why?

Putting together Thought Shrapnel is something that I certainly enjoy doing, but something that takes me away from other things, once you’ve factored in all of the reading, writing, and curating involved in putting out several weekly posts and a newsletter.

I’ve also got a lot of other things right now, with MoodleNet getting closer to a beta launch, and recently becoming a Scout Leader.

So I’m pressing pause for Lent, and have already notified the awesome people who support Thought Shrapnel via Patreon. It will be back after Easter!

Human societies, hierarchy, and networks

Human societies and cultures are complex and messy. That means if we want to even begin to start understanding them, we need to simplify. This approach from Harold Jarche, based on David Ronfeldt’s work, is interesting:

Our current triform society is based on families/communities, a public sector, and a private market sector. But this form, dominated by Markets is unable to deal with the complexities we face globally — climate change, pollution, populism/fanaticism, nuclear war, etc. A quadriform society would be primarily guided by the Network form of organizing. We are making some advances in that area but we still have challenges getting beyond nation states and financial markets.This diagram sums up why I find it so difficult to work within hierarchies: while they're our default form of organising, they're just not very good at dealing with complexity.

Source: Harold Jarche

Success and enthusiasm (quote)

“Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

(Winston Churchill)

Foldable displays are going to make the future pretty amazing

I was in Barcelona on Thursday and Friday last week, right before the start of Mobile World Congress. There were pop-up stores and booths everywhere, including a good-looking Samsung one on Plaça de Catalunya.

While the new five-camera Nokia 9 PureView looks pretty awesome, it’s the foldable displays that have been garnering the most attention. Check out the Huawei Mate X which has just launched at $2,600:

Although we’ve each got one in our family, tablet sales are plummeting, as smartphones get bigger. What’s on offer here seems like exactly the kind of thing I’d use — once they’ve ironed out some of the concerns around reliability/robustness, figured out where the fingerprint sensor and cameras should go, and brought down the price. A 5-inch phone which folds out into an 8-inch tablet? Yes please!

Of course, foldable displays won’t be limited to devices we carry in our pockets. We’re going to see them pretty much everywhere — round our wrists, as part of our clothes, and eventually as ‘wallpaper’ in our houses. Eventually there won’t be a surface on the planet that won’t also potentially be a screen.

So you think you're organised?

This lengthy blog post from Stephen Wolfram, founder and CEO of Wolfram Research is not only incredible in its detail, but reveals the author’s sheer tenacity.

I’m a person who’s only satisfied if I feel I’m being productive. I like figuring things out. I like making things. And I want to do as much of that as I can. And part of being able to do that is to have the best personal infrastructure I can. Over the years I’ve been steadily accumulating and implementing “personal infrastructure hacks” for myself. Some of them are, yes, quite nerdy. But they certainly help me be productive. And maybe in time more and more of them will become mainstream, as a few already have.Wolfram talks about how, as a "hands-on remote CEO" of an 800-person company, he prides himself on automating and streamlining as much as possible.

Wolfram has stuck with various versions of his productivity system for over 30 years. He can search across all of his emails and 100,000(!) notebooks in a single place. It's all quite impressive, really.At an intellectual level, the key to building this infrastructure is to structure, streamline and automate everything as much as possible—while recognizing both what’s realistic with current technology, and what fits with me personally. In many ways, it’s a good, practical exercise in computational thinking, and, yes, it’s a good application of some of the tools and ideas that I’ve spent so long building. Much of it can probably be helpful to lots of other people too; some of it is pretty specific to my personality, my situation and my patterns of activity.

What’s even more impressive, though, is that he experiments with new technologies and sees if they provide an upgrade based on his organisational principles. It reminds me a bit of Clay Shirky’s response to the question of a ‘dream setup’ being that “current optimization is long-term anachronism”.

Well worth a read. I dare you not to be impressed.I’ve described—in arguably quite nerdy detail—how some of my personal technology infrastructure is set up. It’s always changing, and I’m always trying to update it—and for example I seem to end up with lots of bins of things I’m not using any more (yes, I get almost every “interesting” new device or gadget that I find out about).

But although things like devices change, I’ve found that the organizational principles for my infrastructure have remained surprisingly constant, just gradually getting more and more polished. And—at least when they’re based on our very stable Wolfram Language system—I’ve found that the same is true for the software systems I’ve had built to implement them.

Source: Stephen Wolfram

So you think you're organised?

This lengthy blog post from Stephen Wolfram, founder and CEO of Wolfram Research is not only incredible in its detail, but reveals the author’s sheer tenacity.

I’m a person who’s only satisfied if I feel I’m being productive. I like figuring things out. I like making things. And I want to do as much of that as I can. And part of being able to do that is to have the best personal infrastructure I can. Over the years I’ve been steadily accumulating and implementing “personal infrastructure hacks” for myself. Some of them are, yes, quite nerdy. But they certainly help me be productive. And maybe in time more and more of them will become mainstream, as a few already have.Wolfram talks about how, as a "hands-on remote CEO" of an 800-person company, he prides himself on automating and streamlining as much as possible.

Wolfram has stuck with various versions of his productivity system for over 30 years. He can search across all of his emails and 100,000(!) notebooks in a single place. It's all quite impressive, really.At an intellectual level, the key to building this infrastructure is to structure, streamline and automate everything as much as possible—while recognizing both what’s realistic with current technology, and what fits with me personally. In many ways, it’s a good, practical exercise in computational thinking, and, yes, it’s a good application of some of the tools and ideas that I’ve spent so long building. Much of it can probably be helpful to lots of other people too; some of it is pretty specific to my personality, my situation and my patterns of activity.

What’s even more impressive, though, is that he experiments with new technologies and sees if they provide an upgrade based on his organisational principles. It reminds me a bit of Clay Shirky’s response to the question of a ‘dream setup’ being that “current optimization is long-term anachronism”.

Well worth a read. I dare you not to be impressed.I’ve described—in arguably quite nerdy detail—how some of my personal technology infrastructure is set up. It’s always changing, and I’m always trying to update it—and for example I seem to end up with lots of bins of things I’m not using any more (yes, I get almost every “interesting” new device or gadget that I find out about).

But although things like devices change, I’ve found that the organizational principles for my infrastructure have remained surprisingly constant, just gradually getting more and more polished. And—at least when they’re based on our very stable Wolfram Language system—I’ve found that the same is true for the software systems I’ve had built to implement them.

Source: Stephen Wolfram

Blockchains: not so 'unhackable' after all?

As I wrote earlier this month, blockchain technology is not about trust, it’s about distrust. So we shouldn’t be surprised in such an environment that bad actors thrive.

Reporting on a blockchain-based currency (‘cryptocurrency’) hack, MIT Technology Review comment:

We shouldn’t be surprised. Blockchains are particularly attractive to thieves because fraudulent transactions can’t be reversed as they often can be in the traditional financial system. Besides that, we’ve long known that just as blockchains have unique security features, they have unique vulnerabilities. Marketing slogans and headlines that called the technology “unhackable” were dead wrong.The more complicated something is, the more you have to trust technological wizards to verify something is true, then the more problems you're storing up:

But the more complex a blockchain system is, the more ways there are to make mistakes while setting it up. Earlier this month, the company in charge of Zcash—a cryptocurrency that uses extremely complicated math to let users transact in private—revealed that it had secretly fixed a “subtle cryptographic flaw” accidentally baked into the protocol. An attacker could have exploited it to make unlimited counterfeit Zcash. Fortunately, no one seems to have actually done that.It's bad enough when people lose money through these kinds of hacks, but when we start talking about programmable blockchains (so-called 'smart contracts') then we're in a whole different territory.

A smart contract is a computer program that runs on a blockchain network. It can be used to automate the movement of cryptocurrency according to prescribed rules and conditions. This has many potential uses, such as facilitating real legal contracts or complicated financial transactions. Another use—the case of interest here—is to create a voting mechanism by which all the investors in a venture capital fund can collectively decide how to allocate the money.Human culture is dynamic and ever-changing, it's not something we should be hard-coding. And it's certainly not something we should be hard-coding based on the very narrow worldview of those who understand the intricacies of blockchain technology.

It’s particularly delicious that it’s the MIT Technology Review commenting on all of this, given that they’ve been the motive force behind Blockcerts, “the open standard for blockchain credentials” (that nobody actually needs).

Source: MIT Technology Review

Blockchains: not so 'unhackable' after all?

As I wrote earlier this month, blockchain technology is not about trust, it’s about distrust. So we shouldn’t be surprised in such an environment that bad actors thrive.

Reporting on a blockchain-based currency (‘cryptocurrency’) hack, MIT Technology Review comment:

We shouldn’t be surprised. Blockchains are particularly attractive to thieves because fraudulent transactions can’t be reversed as they often can be in the traditional financial system. Besides that, we’ve long known that just as blockchains have unique security features, they have unique vulnerabilities. Marketing slogans and headlines that called the technology “unhackable” were dead wrong.The more complicated something is, the more you have to trust technological wizards to verify something is true, then the more problems you're storing up:

But the more complex a blockchain system is, the more ways there are to make mistakes while setting it up. Earlier this month, the company in charge of Zcash—a cryptocurrency that uses extremely complicated math to let users transact in private—revealed that it had secretly fixed a “subtle cryptographic flaw” accidentally baked into the protocol. An attacker could have exploited it to make unlimited counterfeit Zcash. Fortunately, no one seems to have actually done that.It's bad enough when people lose money through these kinds of hacks, but when we start talking about programmable blockchains (so-called 'smart contracts') then we're in a whole different territory.

A smart contract is a computer program that runs on a blockchain network. It can be used to automate the movement of cryptocurrency according to prescribed rules and conditions. This has many potential uses, such as facilitating real legal contracts or complicated financial transactions. Another use—the case of interest here—is to create a voting mechanism by which all the investors in a venture capital fund can collectively decide how to allocate the money.Human culture is dynamic and ever-changing, it's not something we should be hard-coding. And it's certainly not something we should be hard-coding based on the very narrow worldview of those who understand the intricacies of blockchain technology.

It’s particularly delicious that it’s the MIT Technology Review commenting on all of this, given that they’ve been the motive force behind Blockcerts, “the open standard for blockchain credentials” (that nobody actually needs).

Source: MIT Technology Review

Open Badges and ADCs

As someone who’s been involved with Open Badges since 2012, I’m always interested in the ebbs and flows of the language around their promotion and use.

This article in an article on EdScoop cites a Dean at UC Irvine, who talks about ‘Alternative Digital Credentials’:

Alternative digital credentials — virtual certificates for skill verification — are an institutional imperative, said Gary Matkin, dean of continuing education at the University of California, Irvine, who predicts they will become widely available in higher education within five years.Out of all of the people I’ve spoken to about Open Badges in the past seven years, universities are the ones who least like the term ‘badges’.“Like in the 90s when it was obvious that education was going to begin moving to an online format,” Matkin told EdScoop, “it is now the current progression that institutions will have to begin to issue ADCs.”

The article links to a report by the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) on ADCs which cites seven reasons that they’re an ‘institutional imperative’:

- ADCs (and their non-university equivalents) are already widely offered

- Traditional transcripts are not serving the workforce. The primary failure of traditional transcripts is that they do not connect verified competencies to jobs

- Accrediting agencies are beginning to focus on learning outcomes

- Young adults are demanding shorter and more workplace-relevant learning

- Open education demands ADCs

- Hiring practices increasingly depend on digital searches

- An ADC ecosystem is developing

"Efforts to set universal technical and quality standards for badges and to establish comprehensive repositories for credentials conforming to a single standard will not succeed."You can't lump in quality standards with technical standards. The former is obviously doomed to fail, whereas the latter is somewhat inevitable.

Source: EdScoop

Open Badges and ADCs

As someone who’s been involved with Open Badges since 2012, I’m always interested in the ebbs and flows of the language around their promotion and use.

This article in an article on EdScoop cites a Dean at UC Irvine, who talks about ‘Alternative Digital Credentials’:

Alternative digital credentials — virtual certificates for skill verification — are an institutional imperative, said Gary Matkin, dean of continuing education at the University of California, Irvine, who predicts they will become widely available in higher education within five years.Out of all of the people I’ve spoken to about Open Badges in the past seven years, universities are the ones who least like the term ‘badges’.“Like in the 90s when it was obvious that education was going to begin moving to an online format,” Matkin told EdScoop, “it is now the current progression that institutions will have to begin to issue ADCs.”

The article links to a report by the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) on ADCs which cites seven reasons that they’re an ‘institutional imperative’:

- ADCs (and their non-university equivalents) are already widely offered

- Traditional transcripts are not serving the workforce. The primary failure of traditional transcripts is that they do not connect verified competencies to jobs

- Accrediting agencies are beginning to focus on learning outcomes

- Young adults are demanding shorter and more workplace-relevant learning

- Open education demands ADCs

- Hiring practices increasingly depend on digital searches

- An ADC ecosystem is developing

"Efforts to set universal technical and quality standards for badges and to establish comprehensive repositories for credentials conforming to a single standard will not succeed."You can't lump in quality standards with technical standards. The former is obviously doomed to fail, whereas the latter is somewhat inevitable.

Source: EdScoop

On anger (quote)

“Any person capable of angering you becomes your master. They can anger you only when you permit yourself to be disturbed by them.”

(Epictetus)

On anger (quote)

“Any person capable of angering you becomes your master. They can anger you only when you permit yourself to be disturbed by them.”

(Epictetus)

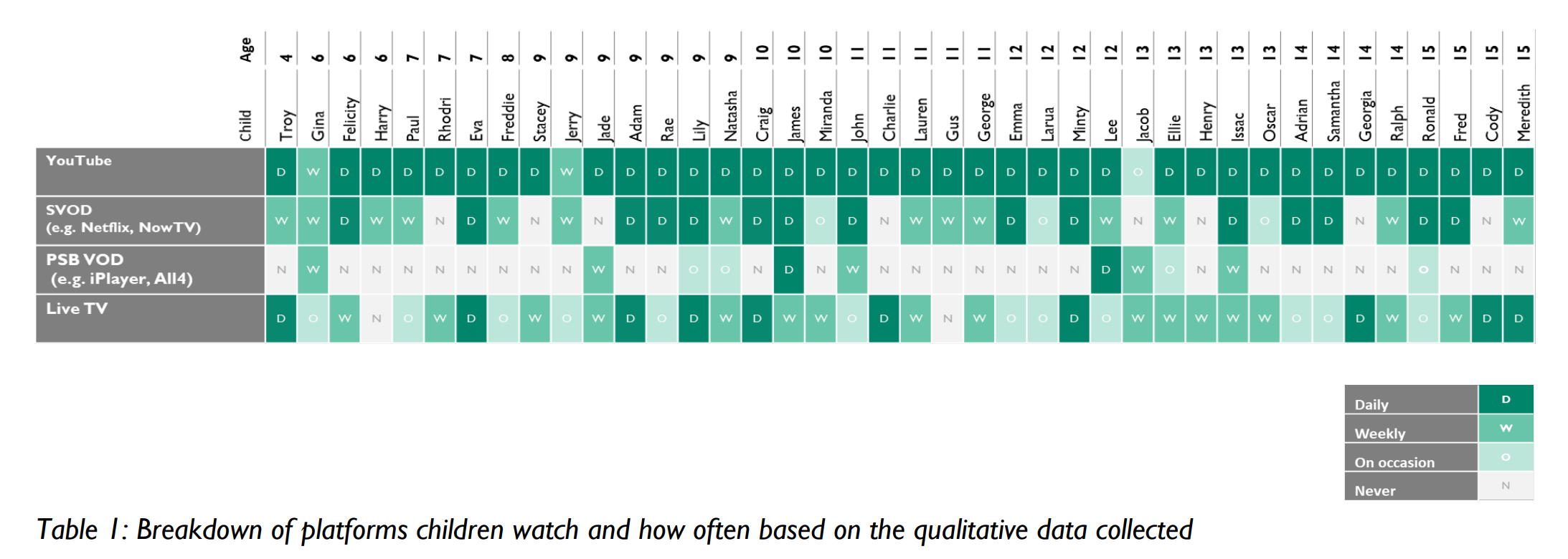

What UK children are watching (and why)

There were only 40 children as part of this Ofcom research, and (as far as I can tell) none were in the North East of England where I live. Nevertheless, as parent to a 12 year-old boy and eight year-old girl, I found the report interesting.

Key findings:I've recently volunteered as an Assistant Scout Leader, and last night went with Scouts and Cubs to the ice-rink in Newcastle on the train. As I'd expect, most of the 12 year-old boys had their smartphones out and most of the girls were talking to one another. The boys were playing some games, but were mostly watching YouTube videos of other people playing games.

- While some children took part in organised after school clubs at least about one a week, not many of them did other or more spontaneous activities (e.g. physically meeting friends or cultivating hobbies) on a regular basis

- Many children used social media and other messaging platforms (e.g. chat functions in games) to continually keep in touch with their friends while at home

- Often children described going out to meet friends face-to-face as ‘too much effort’ and preferred to spend their free time on their own at home

- While some children managed to fit screen time around other offline interests and passions, for many, watching videos was one of the main activities taking up their spare time

- YouTube was the most popular platform for children to consume video content, followed by Netflix. Although still present in many children’s lives, Public Service Broadcasters Video On Demand] platforms and live TV were used more rarely and seen as less relevant to children like them

- Many parents had attempted to enforce rules about online video watching, especially with younger children. They worried that they could not effectively monitor it, as opposed to live or on-demand TV, which was usually watched on the main TV. Some were frustrated by the amount of time children were spending on personal screens.

All kids with access to screen watch YouTube. Why?

Until I saw my son really level up his gameplay by watching YouTubers play the same games as him, I didn't really get it. There's lots of moral panic about YouTube's algorithms, but there's also a lot to celebrate with the fact that children have a bit more autonomy and control these days.

- The appeal of YouTube also appeared rooted in the characteristics of specific genres of content.

- Some children who watched YouTubers and vloggers seemed to feel a sense of connection with them, especially when they believed that they had something in common

- Many children liked “satisfying” videos which simulated sensory experiences

- Many consumed videos that allowed them to expand on their interests; sometimes in conjunction to doing activities themselves, but sometimes only pursuing them by watching YouTube videos

- These historically ‘offline’ experiences were part of YouTube’s attraction, potentially in contrast to the needs fulfilled by traditional TV.

The appeal of YouTube for many of the children in the sample seemed to be that they were able to feed and advance their interests and hobbies through it. Due to the variety of content available on the platform, children were able to find videos that corresponded with interests they had spoken about enjoying offline; these included crafts, sports, drawing, music, make-up and science. Notably, in some cases, children were watching people on YouTube pursuing hobbies that they did not do themselves or had recently given up offline.Really interesting stuff, and well worth digging into!

Source: Ofcom (via Benedict Evans)

Individual steps to tackle climate change

Tomorrow, pupils at some schools in the UK will walk out and join protests around climate change. There are none in my local area of which I’m aware, but it has got me thinking of how I talk to my own children about this.

The above infographic was created by Seth Wynes and Kimberly Nicholas and is featured in an article about the most effective steps you can take as an individual to tackle climate change.

While these are all important steps (I honestly didn’t know quite how bad transatlantic flights are!) it’s important to bear in mind that industry and big business should bear the brunt here. What they can do dwarfs what we can do individually.

Still, it all counts. And we should get on it. Time’s running out.

Source: phys.org

Games (and learning) mechanics

The average age of those who play video games? Early thirties, and rising. So, I’m happy to say that purchasing Red Dead Redemption 2 is one of the best decisions I’ve made so far in 2019.

It’s an incredible, immersive game within which you could easily lose a few hours at a time. And, just like games like Fortnite, it’s being tweaked and updated after release to improve the playing experience. Particularly the online aspect.

What interests me in particular as an educator and a technologist is the way that the designers are thinking carefully about the in-game mechanics based on what players actually do. It’s easy to theorise what people might do, but what they actually do is a constant surprise to anyone who’s ever designed something they’ve asked another person to use.

Engadget mentions one update to Red Dead that particularly jumped out at me:

The update also brings a new system that highlights especially aggressive players. The more hostile you are, the more visible you will become to other players on the map with an increasingly darkening dot. Your visibility will increase in line with bad deeds such as attacking players and their horses outside of a structured mode, free roam mission or event. But, start behaving, and your visibility will fade over time. Rockstar is also introducing the ability to parlay with an entire posse, rather than individual players, which should also help to reduce how often players are killed by trolls.In other words, anti-social behaviour is being dealt with by games mechanics that make it harder for people to act inappropriately.

But my favourite update?

The update will also see the arrival of bounties. Any player that's overly aggressive and consistently breaks the law with have a bounty placed on their head, and once it's high enough NPC [Non-Playing Characters] bounty hunters will get on your tail. Another mechanism to dissuade griefing but perhaps a missed opportunity to allow players to become temporary bounty hunters and enact some sweet vengeance on the players that keep ruining their gameplay.We have a tendency in education to simply ban things we don't like. That might be excluding people from courses, or ultimately from institutions. However, when it's customers at stake, games designers have a wide range of options to influence the outcomes for the positive.

I think we’ve got a lot still to learn in education from games design.

Source: Engadget

Image by BagoGames used under a CC BY license