Microcast #086 — Strategies for dealing with surveillance capitalism

Over the last year (at least) I've been talking about the dangers of surveillance capitalism. Stephen Haggard picked up on this and, after an email conversation, sent through an audio provocation for disucssion.

If you'd like to join this discussion, feel free to comment on this microcast, or reply with your own thoughts in audio or text format in a part of the web under your control!

Show notes

- Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance (EFF)

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (Shoshana Zuboff)

- Zeugma and syllepsis (Wikipedia)

- General Data Protection Regulation (Wikipedia)

- Hierarchy Is Not the Problem (Richard D. Bartlett)

- Instead of breaking up big tech, let’s break them open (Redecentralize)

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Image cropped and rotated from an original by Tim Gouw

There are many non-essential activities, moths of precious time, and it's worse to take an interest in irrelevant things than do nothing at all

I confess to not yet having read Elizabeth Emens' book The Art of Life Admin but it's definitely on my list to read this year. A recent BBC Worklife article cites the book and the concept of 'attention residue'. This is defined as multiple tasks and obligations which split our attention and reduce our overall performance.

“If you have attention residue, you are basically operating with part of your cognitive resources being busy, and that can have a wide range of impacts – you might not be as efficient in your work, you might not be as good a listener, you may get overwhelmed more easily, you might make errors, or struggle with decisions and your ability to process information.”

Sophie Leroy (associate professor of management at the University of Washington)

Attention residue makes us procrastinate at work, and affects our sleep. And sleep, as I explained in my (unfinished) audiobook #uppingyourgame: a practical guide to personal productivity (v2) is one of the three pillars of productivity.

The other two, if you're wondering, are exercise and nutrition. (While I know very talented people who don't exercise nor look after their bodies, I don't know any very productive people who aren't careful about keeping active and what they put into their bodies.)

Back to attention residue, and as the author of the BBC article points out, getting rid of life admin and the associated attention residue means you can enjoy life a little more, guilt-free:

In my case, the GYLIO experiment proved that self-care is less about carving out time to relax amid chaos, and more about removing to-dos from our crowded lives. With some life admin cleared away, I had a bubble bath and enjoyed the smug delight of a life – momentarily – in order.

Madeleine Dore

For me, sleep is extremely important As I learned when our children were very small, I really can't function properly if I have less than seven hours' sleep for two nights in a row.

As a result, I tend to go to bed early, usually before my wife, and definitely having ensured that I've avoided screens after 21:00. I'm definitely in bed by 22:00 and then read until about 22:30.

That means, as has been happening recently, if I am disturbed around 05:30, I can get up and carve out some quiet time to myself before the family awakens. Usually, though, I sleep until around 06:30 which means that, according to my smartband, I'm well-rested.

While we're on the subject of sleep and sleepiness, if you drink coffee first thing in the morning, you might want to rethink that approach:

I stopped drinking coffee about a year and a half ago, and instead drink around three cups of tea over the course of the day. Otherwise, I've found, it's very easy to use caffeine as an accelerator pedal and alcohol as a brakepedal.

Without productive routines it's easy to become overwhelmed. In an article I shared in last Friday's link roundup about communicating better at work, Michael Natkin, suggests that feeling overwhelmed is a common situation:

We’ve all been there. You’ve got so much on your plate that you don’t know where to start. Things that look like they will take fifteen minutes balloon into five-day poop-storms. Every item you cross off your list seems to spawn three more. The check engine light just went on in your car. And now your boss is chasing you down for an unexpected fire drill.

Michael Natkin

The temptation, when you're feeling overwhelmed, is to try and hide, to let no-one know that you're not coping. But that's a really dangerous approach, and the exact opposite of what you should do.

Instead, Natkin suggests an approach of 'over-communicating' which, he says, engages empathy and invites trust:

- Make a (prioritised) list

- Write an email to your line manager (and anyone else you should inform) giving realistic estimates of when your projects will be complete.

- Agree on a plan, and keep everyone updated

You should ask for feedback on your proposed course of action, he says, rather than giving it as a fait accompli.

I think this is a great strategy. What we all need to realise is that, usually, we were chosen for the position we're in, and therefore we should use that to fuel our confidence and self-esteem. Communicating a plan is always better than hiding.

Finally, a word about admin. Some people absolutely love spreadsheets, get a little thrill when they reconcile transactions, and don't mind filling in forms. If, like me, that sounds like the exact opposite of the things I enjoy doing, then you need some admin support.

You can pay for it, you can ask your employer to provide it, or you can call in favours. Either way, without it, you're going to eventually drown in life admin at home and work admin at the office.

My only bit of advice would be to really set your stall out for this. Don't whine or complain about your workload; instead, explain the situation and the impact of admin on your productivity. Put it in financial terms, if necessary.

What are your tips around "attention residue" and what to do when feeling overwhelmed?

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Image by Max Kleinen. Quotation-as-title by Baltasar Gracián

Friday flaggings

As usual, a mixed bag of goodies, just like you used to get from your favourite sweet shop as a kid. Except I don't hold the bottom of the bag, so you get full value.

Let me know which you found tasty and which ones suck (if you'll pardon the pun).

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Message to Young People: “Learn to Be Alone,” Enjoy Solitude

I don’t know… I think I’d like to say only that [young people] should learn to be alone and try to spend as much time as possible by themselves. I think one of the faults of young people today is that they try to come together around events that are noisy, almost aggressive at times. This desire to be together in order to not feel alone is an unfortunate symptom, in my opinion. Every person needs to learn from childhood how to spend time with oneself. That doesn’t mean he should be lonely, but that he shouldn’t grow bored with himself because people who grow bored in their own company seem to me in danger, from a self-esteem point of view.

Andrei Tarkovsky

This article in Open Culture quotes the film-maker Andrei Tarkovsky. Having just finished my first set of therapy sessions, I have to say that the metaphor of "puting on your own oxygen mask before helping others" would be a good takeaway from it. That sounds selfish, but as Tarkovsky points out here, other approaches can lead to the destruction of self-esteem.

Being a Noob

[T]here are two sources of feeling like a noob: being stupid, and doing something novel. Our dislike of feeling like a noob is our brain telling us "Come on, come on, figure this out." Which was the right thing to be thinking for most of human history. The life of hunter-gatherers was complex, but it didn't change as much as life does now. They didn't suddenly have to figure out what to do about cryptocurrency. So it made sense to be biased toward competence at existing problems over the discovery of new ones. It made sense for humans to dislike the feeling of being a noob, just as, in a world where food was scarce, it made sense for them to dislike the feeling of being hungry.

Paul Graham

I'm not sure about the evolutionary framing, but there's definitely something in this about having the confidence (and humility) to be a 'noob' and learn things as a beginner.

You Aren’t Communicating Nearly Enough

Imagine you were to take two identical twins and give them the same starter job, same manager, same skills, and the same personality. One competently does all of their work behind a veil of silence, not sharing good news, opportunities, or challenges, but just plugs away until asked for a status update. The other does the same level of work but communicates effectively, keeping their manager and stakeholders proactively informed. Which one is going to get the next opportunity for growth?

Michael Natkin

I absolutely love this post. As a Product Manager, I've been talking repeatedly recently about making our open-source project 'legible'. As remote workers, that means over-communicating and, as pointed out in this post, being proactive in that communication. Highly recommended.

The Boomer Blockade: How One Generation Reshaped the Workforce and Left Everyone Behind

This is a profound trend. The average age of incoming CEOs for S&P 500 companies has increased about 14 years over the last 14 years

From 1980 to 2001 the average age of a CEO dropped four years and then from 2005 to 2019 the averare incoming age of new CEOs increased 14 years!

This means that the average birth year of a CEO has not budged since 2005. The best predictor of becoming a CEO of our most successful modern institutions?

Being a baby boomer.

Paul Millerd

Wow. This, via Marginal Revolution, pretty much speaks for itself.

The Ed Tech suitcase

Consider packing a suitcase for a trip. It contains many different items – clothes, toiletries, books, electrical items, maybe food and drink or gifts. Some of these items bear a relationship to others, for example underwear, and others are seemingly unrelated, for example a hair dryer. Each brings their own function, which has a separate existence and relates to other items outside of the case, but within the case, they form a new category, that of “items I need for my trip.” In this sense the suitcase resembles the ed tech field, or at least a gathering of ed tech individuals, for example at a conference

If you attend a chemistry conference and have lunch with strangers, it is highly likely they will nearly all have chemistry degrees and PhDs. This is not the case at an ed tech conference, where the lunch table might contain people with expertise in computer science, philosophy, psychology, art, history and engineering. This is a strength of the field. The chemistry conference suitcase then contains just socks (but of different types), but the ed tech suitcase contains many different items. In this perspective then the aim is not to make the items of the suitcase the same, but to find means by which they meet the overall aim of usefulness for your trip, and are not random items that won’t be needed. This suggests a different way of approaching ed tech beyond making it a discipline.

Martin Weller

At the start of this year, it became (briefly) fashionable among ageing (mainly North American) men to state that they had "never been an edtech guy". Follwed by something something pedagogy or something something people. In this post, Martin Weller uses a handy metaphor to explain that edtech may not be a discipline, but it's a useful field (or area of focus) nonetheless.

Why Using WhatsApp is Dangerous

Backdoors are usually camouflaged as “accidental” security flaws. In the last year alone, 12 such flaws have been found in WhatsApp. Seven of them were critical – like the one that got Jeff Bezos. Some might tell you WhatsApp is still “very secure” despite having 7 backdoors exposed in the last 12 months, but that’s just statistically improbable.

[...]

Don’t let yourself be fooled by the tech equivalent of circus magicians who’d like to focus your attention on one isolated aspect all while performing their tricks elsewhere. They want you to think about end-to-end encryption as the only thing you have to look at for privacy. The reality is much more complicated.

Pavel Durov

Facebook products are bad for you, for society, and for the planet. Choose alternatives and encourage others to do likewise.

Why private micro-networks could be the future of how we connect

The current social-media model isn’t quite right for family sharing. Different generations tend to congregate in different places: Facebook is Boomer paradise, Instagram appeals to Millennials, TikTok is GenZ central. (WhatsApp has helped bridge the generational divide, but its focus on messaging is limiting.)

Updating family about a vacation across platforms—via Instagram stories or on Facebook, for example—might not always be appropriate. Do you really want your cubicle pal, your acquaintance from book club, and your high school frenemy to be looped in as well?

Tanya Basu

Some apps are just before their time. Take Path, for example, which my family used for almost the entire eight years it was around, from 2010 to 2018. The interface was great, the experience cosy, and the knowledge that you weren't sharing with everyone outside of a close circle? Priceless.

'Anonymized' Data Is Meaningless Bullshit

While one data broker might only be able to tie my shopping behavior to something like my IP address, and another broker might only be able to tie it to my rough geolocation, that’s ultimately not much of an issue. What is an issue is what happens when those “anonymized” data points inevitably bleed out of the marketing ecosystem and someone even more nefarious uses it for, well, whatever—use your imagination. In other words, when one data broker springs a leak, it’s bad enough—but when dozens spring leaks over time, someone can piece that data together in a way that’s not only identifiable but chillingly accurate.

Shoshana Wodinsky

This idea of cumulative harm is a particularly difficult one to explain (and prove) not only in the world of data, but in every area of life.

"Hey Google, stop tracking me"

Google recently invented a third way to track who you are and what you view on the web.

[...]

Each and every install of Chrome, since version 54, have generated a unique ID. Depending upon which settings you configure, the unique ID may be longer or shorter.

[...]

So every time you visit a Google web page or use a third party site which uses some Google resource, this ID is sent to Google and can be used to track which website or individual page you are viewing. As Google’s services such as scripts, captchas and fonts are used extensively on the most popular web sites, it’s likely that Google tracks most web pages you visit.

Magic Lasso

Use Firefox. Use multi-account containers and extensions that protect your privacy.

The Golden Age of the Internet and social media is over

In the last year I have seen more and more researchers like danah boyd suggesting that digital literacies are not enough. Given that some on the Internet have weaponized these tools, I believe she is right. Moving beyond digital literacies means thinking about the epistemology behind digital literacies and helping to “build the capacity to truly hear and embrace someone else’s perspective and teaching people to understand another’s view while also holding their view firm” (boyd, March 9, 2018). We can still rely on social media for our news but we really owe it to ourselves to do better in further developing digital literacies, and knowing that just because we have discussions through screens that we should not be so narcissistic to believe that we MUST be right or that the other person is simply an idiot.

Jimmy Young

I'd argue, as I did recently in this talk, that what Young and boyd are talking about here is actually a central tenet of digital literacies.

Image via Introvert doodles

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

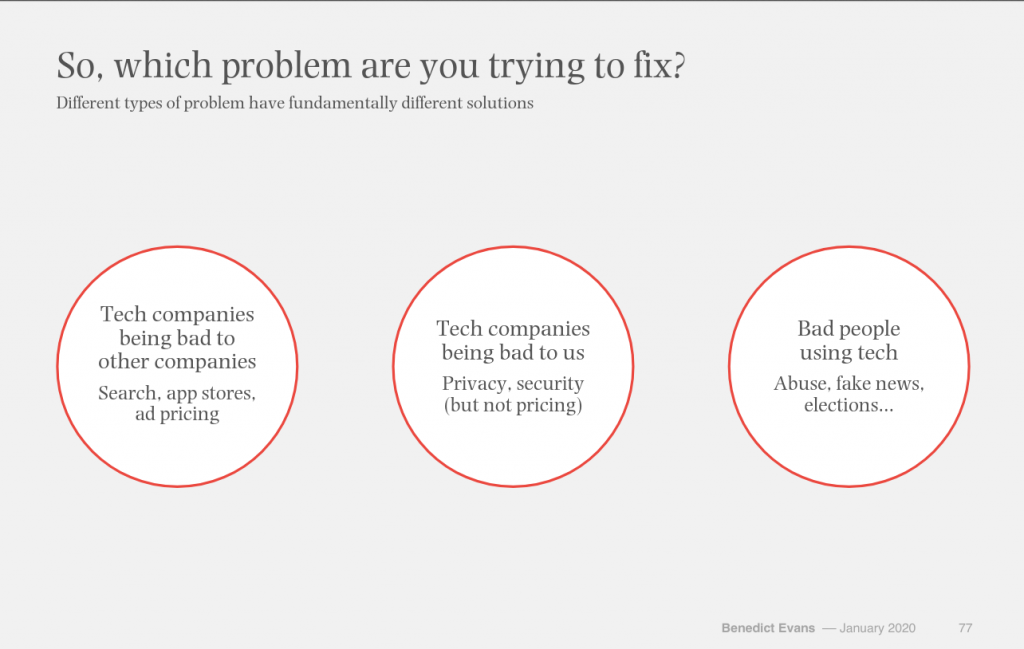

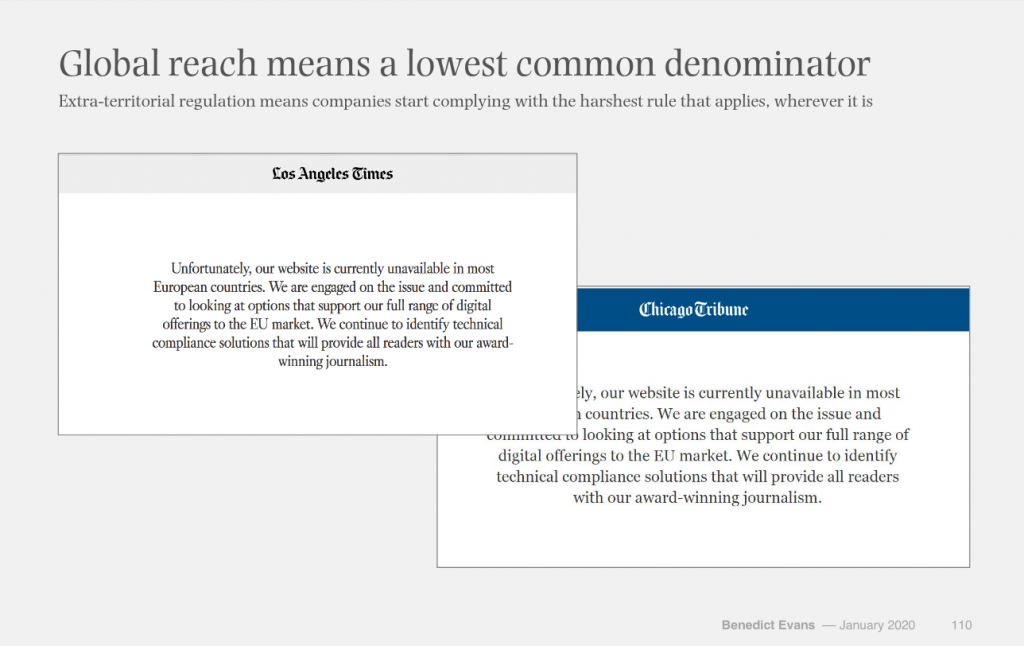

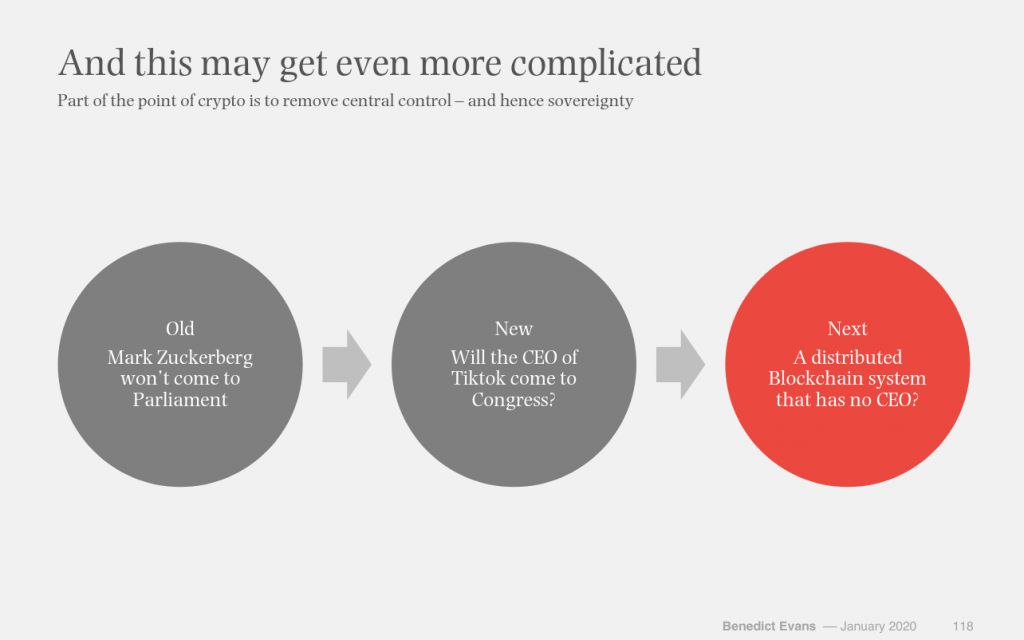

Software ate the world, so all the world’s problems get expressed in software

Benedict Evans recently posted his annual 'macro trends' slide deck. It's incredibly insightful, and work of (minimalist) art. This article's title comes from his conclusion, and you can see below which of the 128 slides jumped out at me from deck:

For me, what the deck as a whole does is place some of the issues I've been thinking about in a wider context.

My team is building a federated social network for educators, so I'm particularly tuned-in to conversations about the effect social media is having on society. A post by Harold Jarche where he writes about his experience of Twitter as a rage machine caught my attention, especially the part where he talks about how people are happy to comment based on the 'preview' presented to them in embedded tweets:

Research on the self-perception of knowledge shows how viewing previews without going to the original article gives an inflated sense of understanding on the subject, “audiences who only read article previews are overly confident in their knowledge, especially individuals who are motivated to experience strong emotions and, thus, tend to form strong opinions.” Social media have created a worldwide Dunning-Kruger effect. Our collective self-perception of knowledge acquired through social media is greater than it actually is.

Harold Jarche

I think our experiment with general-purpose social networks is slowly coming to an end, or at least will do over the next decade. What I mean is that, while we'll still have places where you can broadcast anything to anyone, the digital environments we'll spend more time will be what Venkatesh Rao calls the 'cozyweb':

Unlike the main public internet, which runs on the (human) protocol of “users” clicking on links on public pages/apps maintained by “publishers”, the cozyweb works on the (human) protocol of everybody cutting-and-pasting bits of text, images, URLs, and screenshots across live streams. Much of this content is poorly addressable, poorly searchable, and very vulnerable to bitrot. It lives in a high-gatekeeping slum-like space comprising slacks, messaging apps, private groups, storage services like dropbox, and of course, email.

Venkatesh Rao

That's on a personal level. I should imagine organisational spaces will be a bit more organised. Back to Jarche:

We need safe communities to take time for reflection, consideration, and testing out ideas without getting harassed. Professional social networks and communities of practices help us make sense of the world outside the workplace. They also enable each of us to bring to bear much more knowledge and insight that we could do on our own.

Harold Jarche

...or to use Rao's diagram which is so-awful-it's-useful:

Of course, blockchain/crypto could come along and solve all of our problems. Except it won't. Humans are humans (are humans).

Ever since Eli Parisier's TED talk urging us to beware online "filter bubbles" people have been wringing their hands about ensuring we have 'balance' in our networks.

Interestingly, some recent research by the Reuters Institute at Oxford University, paints a slightly different picture. The researcher, Dr Richard Fletcher begins by investigating how people access the news.

Fletcher draws a distinction between different types of personalisation:

Self-selected personalisation refers to the personalisations that we voluntarily do to ourselves, and this is particularly important when it comes to news use. People have always made decisions in order to personalise their news use. They make decisions about what newspapers to buy, what TV channels to watch, and at the same time which ones they would avoid

Academics call this selective exposure. We know that it's influenced by a range of different things such as people's interest levels in news, their political beliefs and so on. This is something that has pretty much always been true.

Pre-selected personalisation is the personalisation that is done to people, sometimes by algorithms, sometimes without their knowledge. And this relates directly to the idea of filter bubbles because algorithms are possibly making choices on behalf of people and they may not be aware of it.

The reason this distinction is particularly important is because we should avoid comparing pre-selected personalisation and its effects with a world where people do not do any kind of personalisation to themselves. We can't assume that offline, or when people are self-selecting news online, they're doing it in a completely random way. People are always engaging in personalisation to some extent and if we want to understand the extent of pre-selected personalisation, we have to compare it with the realistic alternative, not hypothetical ideals.

Dr Richard Fletcher

Read the article for the details, but the takeaways for me were twofold. First, that we might be blaming social media for wider and deeper divisons within society, and second, that teaching people to search for information (rather than stumble across it via feeds) might be the best strategy:

People who use search engines for news on average use more news sources than people who don't. More importantly, they're more likely to use sources from both the left and the right.

Dr Richard Fletcher

People who rely mainly on self-selection tend to have fairly imbalanced news diets. They either have more right-leaning or more left-leaning sources. People who use search engines tend to have a more even split between the two.

Useful as it is, what I think this research misses out is the 'black box' algorithms that seek to keep people engaged and consuming content. YouTube is the poster child for this. As Jarche comments:

We are left in a state of constant doubt as conspiratorial content becomes easier to access on platforms like YouTube than accessing solid scientific information in a journal, much of which is behind a pay-wall and inaccessible to the general public.

Harold Jarche

This isn't an easy problem to solve.

We might like to pretend that human beings are rational agents, but this isn't actually true. Let's take something like climate change. We're not arguing about the facts here, we're arguing about politics. Adrian Bardon, writing in Fast Company, writes:

In theory, resolving factual disputes should be relatively easy: Just present evidence of a strong expert consensus. This approach succeeds most of the time, when the issue is, say, the atomic weight of hydrogen.

But things don’t work that way when the scientific consensus presents a picture that threatens someone’s ideological worldview. In practice, it turns out that one’s political, religious, or ethnic identity quite effectively predicts one’s willingness to accept expertise on any given politicized issue.

Adrian Bardon

This is pretty obvious when we stop to think about it for a moment; beliefs are bound up with identity, and that's not something that's so easy to change.

In ideologically charged situations, one’s prejudices end up affecting one’s factual beliefs. Insofar as you define yourself in terms of your cultural affiliations, information that threatens your belief system—say, information about the negative effects of industrial production on the environment—can threaten your sense of identity itself. If it’s part of your ideological community’s worldview that unnatural things are unhealthful, factual information about a scientific consensus on vaccine or GM food safety feels like a personal attack.

Adrian Bardon

So how do we change people's minds when they're objectively wrong? Brian Resnick, writing for Vox, suggests the best approach might be 'deep canvassing':

Giving grace. Listening to a political opponent’s concerns. Finding common humanity. In 2020, these seem like radical propositions. But when it comes to changing minds, they work.

[...]

The new research shows that if you want to change someone’s mind, you need to have patience with them, ask them to reflect on their life, and listen. It’s not about calling people out or labeling them fill-in-the-blank-phobic. Which makes it feel like a big departure from a lot of the current political dialogue.

Brian Resnick

This approach, it seems, works:

So it seems there is some hope to fixing the world's problems. It's just that the solutions point towards doing the hard work of talking to people and not just treating them as containers for opinions to shoot down at a distance.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Friday featherings

Behold! The usual link round-up of interesting things I've read in the last week.

Feel free to let me know if anything particularly resonated with you via the comments section below...

Part I - What is a Weird Internet Career?

Weird Internet Careers are the kinds of jobs that are impossible to explain to your parents, people who somehow make a living from the internet, generally involving a changing mix of revenue streams. Weird Internet Career is a term I made up (it had no google results in quotes before I started using it), but once you start noticing them, you’ll see them everywhere.

Gretchen McCulloch (All Things Linguistic)

I love this phrase, which I came across via Dan Hon's newsletter. This is the first in a whole series of posts, which I am yet to explore in its entirety. My aim in life is now to make my career progressively more (internet) weird.

Nearly half of Americans didn’t go outside to recreate in 2018. That has the outdoor industry worried.

While the Outdoor Foundation’s 2019 Outdoor Participation Report showed that while a bit more than half of Americans went outside to play at least once in 2018, nearly half did not go outside for recreation at all. Americans went on 1 billion fewer outdoor outings in 2018 than they did in 2008. The number of adolescents ages 6 to 12 who recreate outdoors has fallen four years in a row, dropping more than 3% since 2007

The number of outings for kids has fallen 15% since 2012. The number of moderate outdoor recreation participants declined, and only 18% of Americans played outside at least once a week.

Jason Blevins (The Colorado Sun)

One of Bruce Willis' lesser-known films is Surrogates (2009). It's a short, pretty average film with a really interesting central premise: most people stay at home and send their surrogates out into the world. Over a decade after the film was released, a combination of things (including virulent viruses, screen-focused leisure time, and safety fears) seem to suggest it might be a predictor of our medium-term future.

I’ll Never Go Back to Life Before GDPR

It’s also telling when you think about what lengths companies have had to go through to make the EU versions of their sites different. Complying with GDPR has not been cheap. Any online business could choose to follow GDPR by default across all regions and for all visitors. It would certainly simplify things. They don’t, though. The amount of money in data collection is too big.

Jill Duffy (OneZero)

This is a strangely-titled article, but a decent explainer on what the web looks and feels like to those outside the EU. The author is spot-on when she talks about how GDPR and the recent California Privacy Law could be applied everywhere, but they're not. Because surveillance capitalism.

You Are Now Remotely Controlled

The belief that privacy is private has left us careening toward a future that we did not choose, because it failed to reckon with the profound distinction between a society that insists upon sovereign individual rights and one that lives by the social relations of the one-way mirror. The lesson is that privacy is public — it is a collective good that is logically and morally inseparable from the values of human autonomy and self-determination upon which privacy depends and without which a democratic society is unimaginable.

Shoshana Zuboff (The New York Times)

I fear that the length of Zuboff's (excellent) book on surveillance capitalism, her use of terms in this article such as 'epistemic inequality, and the subtlety of her arguments, may mean that she's preaching to the choir here.

How to Raise Media-Savvy Kids in the Digital Age

The next time you snap a photo together at the park or a restaurant, try asking your child if it’s all right that you post it to social media. Use the opportunity to talk about who can see that photo and show them your privacy settings. Or if a news story about the algorithms on YouTube comes on television, ask them if they’ve ever been directed to a video they didn’t want to see.

Meghan Herbst (WIRED)

There's some useful advice in this WIRED article, especially that given by my friend Ian O'Byrne. The difficulty I've found is when one of your kids becomes a teenager and companies like Google contact them directly telling them they can have full control of their accounts, should they wish...

Control-F and Building Resilient Information Networks

One reason the best lack conviction, though, is time. They don’t have the time to get to the level of conviction they need, and it’s a knotty problem, because that level of care is precisely what makes their participation in the network beneficial. (In fact, when I ask people who have unintentionally spread misinformation why they did so, the most common answer I hear is that they were either pressed for time, or had a scarcity of attention to give to that moment)

But what if — and hear me out here — what if there was a way for people to quickly check whether linked articles actually supported the points they claimed to? Actually quoted things correctly? Actually provided the context of the original from which they quoted

And what if, by some miracle, that function was shipped with every laptop and tablet, and available in different versions for mobile devices?

This super-feature actually exists already, and it’s called control-f.

Roll the animated GIF!

Mike Caulfield (Hapgood)

I find it incredible, but absolutely believable, that only around 10% of internet users know how to use Ctrl-F to find something within a web page. On mobile, it's just as easy, as there's an option within most (all?) browsers to 'search within page'. I like Mike's work, as not only is it academic, it's incredibly practical.

EdX launches for-credit credentials that stack into bachelor's degrees

The MicroBachelors also mark a continued shift for EdX, which made its name as one of the first MOOC providers, to a wider variety of educational offerings

In 2018, EdX announced several online master's degrees with selective universities, including the Georgia Institute of Technology and the University of Texas at Austin.

Two years prior, it rolled out MicroMasters programs. Students can complete the series of graduate-level courses as a standalone credential or roll them into one of EdX's master's degrees.

That stackability was something EdX wanted to carry over into the MicroBachelors programs, Agarwal said. One key difference, however, is that the undergraduate programs will have an advising component, which the master's programs do not.

Natalie Schwartz (Education Dive)

This is largely a rewritten press release with a few extra links, but I found it interesting as it's a concrete example of a couple of things. First, the ongoing shift in Higher Education towards students-as-customers. Second, the viability of microcredentials as a 'stackable' way to build a portfolio of skills.

Note that, as a graduate of degrees in the Humanities, I'm not saying this approach can be used for everything, but for those using Higher Education as a means to an end, this is exactly what's required.

How much longer will we trust Google’s search results?

Today, I still trust Google to not allow business dealings to affect the rankings of its organic results, but how much does that matter if most people can’t visually tell the difference at first glance? And how much does that matter when certain sections of Google, like hotels and flights, do use paid inclusion? And how much does that matter when business dealings very likely do affect the outcome of what you get when you use the next generation of search, the Google Assistant?

Dieter Bohn (The Verge)

I've used DuckDuckGo as my go-to search engine for years now. It used to be that I'd have to switch to Google for around 10% of my searches. That's now down to zero.

Coaching – Ethics

One of the toughest situations for a product manager is when they spot a brewing ethical issue, but they’re not sure how they should handle the situation. Clearly this is going to be sensitive, and potentially emotional. Our best answer is to discover a solution that does not have these ethical concerns, but in some cases you won’t be able to, or may not have the time.

[...]

I rarely encourage people to leave their company, however, when it comes to those companies that are clearly ignoring the ethical implications of their work, I have and will continue to encourage people to leave.

Marty Cagan (SVPG)

As someone with a sensitive radar for these things, I've chosen to work with ethical people and for ethical organisations. As Cagan says in this post, if you're working for a company that ignores the ethical implications of their work, then you should leave. End of story.

Image via webcomic.name

Microcast #085 — Extensions for Mozilla Firefox

In the last quarter of 2019, I got rid of my Google Pixelbook and Chromebox, and switched full-time to Linux and Firefox.

I still need to dip into Chromium occasionally to use Loom but, on the whole, I'm really happy with my new setup. In this microcast, I go through my Firefox extensions and the reasons I have them installed.

Show notes

The following are links to the Firefox Add-ons directory:

- Awesome Screenshot

- ColorZilla

- Containers Sync

- Dark Reader

- Decentraleyes

- Disconnect

- DownloadThemAll!

- Firefox Multi-Account Containers

- Floccus

- Fraidycat

- LessPass

- Livemarks

- Momentum

- NoPlugin

- Plasma integration

- Privacy Badger

- RSSPreview

- Terms of Service; Didn't Read

- The Camelizer

- uBlock Origin

- Video DownloadHelper

- Web Developer

- Zoom Scheduler

To others we are not ourselves but a performer in their lives cast for a part we do not even know that we are playing

Surveillance, technology, and society

Last week, the London Metropolitan Police ('the Met') proudly announced that they've begun using 'LFR', which is their neutral-sounding acronym for something incredibly invasive to the privacy of everyday people in Britain's capital: Live Facial Recognition.

It's obvious that the Met expect some pushback here:

The Met will begin operationally deploying LFR at locations where intelligence suggests we are most likely to locate serious offenders. Each deployment will have a bespoke ‘watch list’, made up of images of wanted individuals, predominantly those wanted for serious and violent offences.

At a deployment, cameras will be focused on a small, targeted area to scan passers-by. The cameras will be clearly signposted and officers deployed to the operation will hand out leaflets about the activity. The technology, which is a standalone system, is not linked to any other imaging system, such as CCTV, body worn video or ANPR.

London Metropolitan Police

Note the talk of 'intelligence' and 'bespoke watch lists', as well as promises that LFR will not be linked any other systems. (ANPR, for those not familiar with it, is 'Automatic Number Plate Recognition'.) This, of course, is the thin end of the wedge and how these things start — in a 'targeted' way. They're expanded later, often when the fuss has died down.

Meanwhile, a lot of controversy surrounds an app called Clearview AI which scrapes publicly-available data (e.g. Twitter or YouTube profiles) and applies facial recognition algorithms. It's already in use by law enforcement in the USA.

The size of the Clearview database dwarfs others in use by law enforcement. The FBI's own database, which taps passport and driver's license photos, is one of the largest, with over 641 million images of US citizens.

The Clearview app isn't available to the public, but the Times says police officers and Clearview investors think it will be in the future.

The startup said in a statement Tuesday that its "technology is intended only for use by law enforcement and security personnel. It is not intended for use by the general public."

Edward Moyer (CNET)

So there we are again, the technology is 'intended' for one purpose, but the general feeling is that it will leak out into others. Imagine the situation if anyone could identify almost anyone on the planet simply by pointing their smartphone at them for a few seconds?

This is a huge issue, and one that politicians and lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic are both ill-equipped to deal with and particularly concerned about. As the BBC reports, the European Commission is considering a five-year ban on facial recognition in public spaces while it figures out how to regulate the technology:

The Commission set out its plans in an 18-page document, suggesting that new rules will be introduced to bolster existing regulation surrounding privacy and data rights.

It proposed imposing obligations on both developers and users of artificial intelligence, and urged EU countries to create an authority to monitor the new rules.

During the ban, which would last between three and five years, "a sound methodology for assessing the impacts of this technology and possible risk management measures could be identified and developed".

BBC News

I can't see the genie going back in this particular bottle and, as Ian Welsh puts it, this is the end of public anonymity. He gives the examples of the potential for all kinds of abuse, from an increase in rape, to abuse by corporations, to an increase in parental surveillance of children.

The larger issue is this: people who are constantly under surveillance become super conformers out of defense. Without true private time, the public persona and the private personality tend to collapse together. You need a backstage — by yourself and with a small group of friends to become yourself. You need anonymity.

When everything you do is open to criticism by everyone, you will become timid and conforming.

When governments, corporations, schools and parents know everything, they will try to control everything. This often won’t be for your benefit.

Ian Welsh

We already know that self-censorship is the worst kind of censorship, and live facial recognition means we're going to have to do a whole lot more of it in the near future.

So what can we do about it? Welsh thinks that this technology should be made illegal, which is one option. However, you can't un-invent technologies. So live facial recognition is going to be used (lawfully) by some organisations, even if it were restricted to state operatives. I'm not sure if that's better or worse than everyone having it?

At a recent workshop I ran, I was talking during one of the breaks to one person who couldn't really see the problem I had raised about surveillance capitalism. I have to wonder if they would have a problem with live facial recognition? From our conversation, I'd suspect not.

Remember that facial recognition is not 100% accurate and (realistically) never can be. So there will be false positives. Let's say your face ends up on a 'watch list' or a 'bad actor' database shared with many different agencies and retailers. All of a sudden, you've got yourself a very big problem.

As BuzzFeed News reports, around half of US retailers are either using live facial recognition, or have plans to use it. At the moment, companies like FaceFirst do not facilitate the sharing of data across their clients, but you can see what's coming next:

[Peter Trepp, CEO of FaceFirst] said the database is not shared with other retailers or with FaceFirst directly. All retailers have their own policies, but Trepp said often stores will offer not to press charges against apprehended shoplifters if they agree to opt into the store’s shoplifter database. The files containing the images and identities of people on “the bad guy list” are encrypted and only accessible to retailers using their own systems, he said.

FaceFirst automatically purges visitor data that does not match information in a criminal database every 14 days, which is the company’s minimum recommendation for auto-purging data. It’s up to the retailer if apprehended shoplifters or people previously on the list can later opt out of the database.

Leticia Miranda (BuzzFeed News)

There is no opt-in, no consent sought or gathered by retailers. This is a perfect example of technology being light years ahead of lawmaking.

This is all well-and-good in situations where adults are going into public spaces, but what about schools, where children are often only one step above prisoners in terms of the rights they enjoy?

Recode reports that, in schools, the surveillance threat to students goes beyond facial recognition. So long as authorities know generally what a student looks like, they can track them everywhere they go:

Appearance Search can find people based on their age, gender, clothing, and facial characteristics, and it scans through videos like facial recognition tech — though the company that makes it, Avigilon, says it doesn’t technically count as a full-fledged facial recognition tool

Even so, privacy experts told Recode that, for students, the distinction doesn’t necessarily matter. Appearance Search allows school administrators to review where a person has traveled throughout campus — anywhere there’s a camera — using data the system collects about that person’s clothing, shape, size, and potentially their facial characteristics, among other factors. It also allows security officials to search through camera feeds using certain physical descriptions, like a person’s age, gender, and hair color. So while the tool can’t say who the person is, it can find where else they’ve likely been.

Rebecca Heilweil (Recode)

This is a good example of the boundaries of technology that may-or-may-not be banned at some point in the future. The makers of Appearance Search, Avigilon, claim that it's not facial recognition technology because the images it captures and analyses are tied to the identity of a particular person:

Avigilon’s surveillance tool exists in a gray area: Even privacy experts are conflicted over whether or not it would be accurate to call the system facial recognition. After looking at publicly available content about Avigilon, Leong said it would be fairer to call the system an advanced form of characterization, meaning that the system is making judgments about the attributes of that person, like what they’re wearing or their hair, but it’s not actually claiming to know their identity.

Rebecca Heilweil (Recode)

You can give as many examples of the technology being used for good as you want — there's one in this article about how the system helped discover a girl was being bullied, for example — but it's still intrusive surveillance. There are other ways of getting to the same outcome.

We do not live in a world of certainty. We live in a world where things are ambiguous, unsure, and sometimes a little dangerous. While we should seek to protect one another, and especially those who are most vulnerable in society, we should think about the harm we're doing by forcing people to live the totality of their lives in public.

What does that do to our conceptions of self? To creativity? To activism? Live facial recognition technology, as well as those technologies that exist in a grey area around it, is the hot-button issue of the 2020s.

Image by Kirill Sharkovski. Quotation-as-title by Elizabeth Bibesco.

Friday festoonings

Check out these things I read and found interesting this week. Thanks to some positive feedback, I've carved out time for some commentary, and changed the way this link roundup is set out.

Let me know what you think! What did you find most interesting?

Maps Are Biased Against Animals

Critics may say that it is unreasonable to expect maps to reflect the communities or achievements of nonhumans. Maps are made by humans, for humans. When beavers start Googling directions to a neighbor’s dam, then their homes can be represented! For humans who use maps solely to navigate—something that nonhumans do without maps—man-made roads are indeed the only features that are relevant. Following a map that includes other information may inadvertently lead a human onto a trail made by and for deer.

But maps are not just tools to get from points A to B. They also relay new and learned information, document evolutionary changes, and inspire intrepid exploration. We operate on the assumption that our maps accurately reflect what a visitor would find if they traveled to a particular area. Maps have immense potential to illustrate the world around us, identifying all the important features of a given region. By that definition, the current maps that most humans use fall well short of being complete. Our definition of what is “important” is incredibly narrow.

Ryan Huling (WIRED)

Cartography is an incredibly powerful tool. We've known for a long time that “the map is not the territory” but perhaps this is another weapon in the fight against climate change and the decline in diversity of species?

Why Actually Principled People Are Difficult (Glenn Greenwald Edition)

Then you get people like Greenwald, Assange, Manning and Snowden. They are polarizing figures. They are loved or hated. They piss people off.

They piss people off precisely because they have principles they consider non-negotiable. They will not do the easy thing when it matters. They will not compromise on anything that really matters.

That’s breaking the actual social contract of “go along to get along”, “obey authority” and “don’t make people uncomfortable.” I recently talked to a senior activist who was uncomfortable even with the idea of yelling at powerful politicians. It struck them as close to violence.

So here’s the thing, people want men and women of principle to be like ordinary people.

They aren’t. They can’t be. If they were, they wouldn’t do what they do. Much of what you may not like about a Greenwald or Assange or Manning or Snowden is why they are what they are. Not just the principle, but the bravery verging on recklessness. The willingness to say exactly what they think, and do exactly what they believe is right even if others don’t.

Ian Welsh

Activists like Greta Thunberg and Edward Snowden are the closest we get to superheroes, to people who stand for the purest possible version of an idea. This is why we need them — and why we're so disappointed when they turn out to be human after all.

Explicit education

Students’ not comprehending the value of engaging in certain ways is more likely to be a failure in our teaching than their willingness to learn (especially if we create a culture in which success becomes exclusively about marks and credentialization). The question we have to ask is if what we provide as ‘university’ goes beyond the value of what our students can engage with outside of our formal offer.

Dave White

This is a great post by Dave, who I had the pleasure of collaborating with briefly during my stint at Jisc. I definitely agree that any organisation walks a dangerous path when it becomes overly-fixated on the 'how' instead of the 'what' and the 'why'.

What Are Your Rules for Life? These 11 Expressions (from Ancient History) Might Help

The power of an epigram or one of these expressions is that they say a lot with a little. They help guide us through the complexity of life with their unswerving directness. Each person must, as the retired USMC general and former Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis, has said, “Know what you will stand for and, more important, what you won’t stand for.” “State your flat-ass rules and stick to them. They shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone.”

Ryan Holiday

Of the 11 expressions here, I have to say that other than memento mori (“remember you will die”) I particularly like semper anticus (“always forward”) which I'm going to print out in a fancy font and stick on the wall of my home office.

Dark Horse Discord

In a hypothetical world, you could get a Discord (or whatever is next) link for your new job tomorrow – you read some wiki and meta info, sort yourself into your role you’d, and then are grouped with the people who you need to collaborate with on a need be basis. All wrapped in one platform. Maybe you have an HR complaint - drop it in #HR where you can’t read the messages but they can, so it’s a blind 1 way conversation. Maybe there is a #help channel, where you ping you write your problems and the bot pings people who have expertise based on keywords. There’s a lot of things you can do with this basic design.

Mule's Musings

What is described in this post is a bit of a stretch, but I can see it: a world where work is organised a bit like how gamers organisers in chat channels. Something to keep an eye on, as the interplay between what's 'normal' and what's possible with communications technology changes and evolves.

The Edu-Decade That Was: Unfounded Optimism?

What made the last decade so difficult is how education institutions let corporations control the definitions so that a lot of “study and ethical practice” gets left out of the work. With the promise of ease of use, low-cost, increased student retention (or insert unreasonable-metric-claim here), etc. institutions are willing to buy into technology without regard to accessibility, scalability, equity and inclusion, data privacy or student safety, in hope of solving problem X that will then get to be checked off of an accreditation list. Or worse, with the hope of not having to invest in actual people and local infrastructure.

Geoff Cain (Brainstorm in progress)

It's nice to see a list of some positives that came out of the last decades, and for microcredentials and badging to be on that list.

When Is a Bird a ‘Birb’? An Extremely Important Guide

First, let’s consider the canonized usages. The subreddit r/birbs defines a birb as any bird that’s “being funny, cute, or silly in some way." Urban Dictionary has a more varied set of definitions, many of which allude to a generalized smallness. A video on the youtube channel Lucidchart offers its own expansive suggestions: All birds are birbs, a chunky bird is a borb, and a fluffed-up bird is a floof. Yet some tension remains: How can all birds be birbs if smallness or cuteness are in the equation? Clearly some birds get more recognition for an innate birbness.

Asher Elbein (Audubon magazine)

A fun article, but also an interesting one when it comes to ambiguity, affinity groups, and internet culture.

Why So Many Things Cost Exactly Zero

“Now, why would Gmail or Facebook pay us? Because what we’re giving them in return is not money but data. We’re giving them lots of data about where we go, what we eat, what we buy. We let them read the contents of our email and determine that we’re about to go on vacation or we’ve just had a baby or we’re upset with our friend or it’s a difficult time at work. All of these things are in our email that can be read by the platform, and then the platform’s going to use that to sell us stuff.”

Fiona Scott Morton (Yale business school) quoted by Peter coy (Bloomberg Businessweek)

Regular readers of Thought Shrapnel know all about surveillance capitalism, but it's good to see these explainers making their way to the more mainstream business press.

Your online activity is now effectively a social ‘credit score’

The most famous social credit system in operation is that used by China's government. It "monitors millions of individuals' behavior (including social media and online shopping), determines how moral or immoral it is, and raises or lowers their "citizen score" accordingly," reported Atlantic in 2018.

"Those with a high score are rewarded, while those with a low score are punished." Now we know the same AI systems are used for predictive policing to round up Muslim Uighurs and other minorities into concentration camps under the guise of preventing extremism.

Violet Blue (Engadget)

Some (more prudish) people will write this article off because it discusses sex workers, porn, and gay rights. But the truth is that all kinds of censorship start with marginalised groups. To my mind, we're already on a trajectory away from Silicon Valley and towards Chinese technology. Will we be able to separate the tech from the morality?

Panicking About Your Kids’ Phones? New Research Says Don’t

The researchers worry that the focus on keeping children away from screens is making it hard to have more productive conversations about topics like how to make phones more useful for low-income people, who tend to use them more, or how to protect the privacy of teenagers who share their lives online.

“Many of the people who are terrifying kids about screens, they have hit a vein of attention from society and they are going to ride that. But that is super bad for society,” said Andrew Przybylski, the director of research at the Oxford Internet Institute, who has published several studies on the topic.

Nathaniel Popper (The New York Times)

Kids and screentime is just the latest (extended) moral panic. Overuse of anything causes problems, smartphones, games consoles, and TV included. What we need to do is to help our children find balance in all of this, which can be difficult for the first generation of parents navigating all of this on the frontline.

Gorgeous header art via the latest Facebook alternative, planetary.social

Microcast #084 - Chris Dixon on RSS, crypto, and community ownership of the internet

I don't often listen to the a16z podcast but for some reason I decided to listen to an episode about the past, present, and future of the internet while out for a long walk.

In it, Jonah Peretti, founder and CEO of Buzzfeed, interviews Chris Dixon, a partner at VC firm Andreessen Horowitz. A section of it really struck me, which I'd like to share with you now.

I'd be interested in your thoughts on it, too. Are you optimistic about the kind of approach that Dixon outlines?

Show notes

How you do anything is how you do everything

So said Derek Sivers, although I suspect that, originally, it's probably a core principle of Zen Buddhism. In this article I want to talk about management and leadership. But also about emotional intelligence and integrity.

I currently spend part of my working life as a Product Manager. At some organisations, this means that you're in charge of the budget, and pull in colleagues from different disciplines. For example, a designer you're working with on a particular project might report to the Head of UX. Matrix-style management and internal budgeting keeps track of everything.

This approach can get complicated so, at other companies (like the one I'm working with), the Product Manager manages both people and product. It's a lot of work, as both can be complicated.

I think I'm OK at managing people, and other people say I'm good at it, but it's not my favourite thing in the world to do.

That's why, when hiring, I try to do so in one of three ways. Ideally, I want to hire people with whom at least one member of the existing team has already worked and can vouch for. If that doesn't work, then I'm looking for people vouched for my the networks of which the team are part. Failing that, I'm trying to find people who don't wait for direction, but know how to get on with things that need doing.

It's an approach I've developed from the work of Laura Thomson. She's a former colleague at Mozilla, and an advocate of a chaordic style of management and self-organising ducks:

Instead of having ‘all your ducks in a row’ the analogy in chaordic management is to have ‘self-organising ducks’. The idea is to give people enough autonomy, knowledge and skill to be able to do the management themselves.

As I've said before, the default way of organising human beings is hierarchy. That doesn't mean it's the best way. Hierachy tends to lean on processes, paperwork and meetings to 'get things done' but even a cursory glance at Open Source projects shows that all of this isn't strictly necessary.

Last week, a new-ish member of the team said that I can be "too nice". I'm still processing that and digging into what they meant, but I then ended up reading an article by Roddy Millar for Fast Company entitled Here’s why being likable may make you a less effective leader.

It's a slightly oddly-framed article that quotes Prof. Karen Cates from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management :

Leaders should not put likability above effectiveness. There are times when the humor and smiles need to go and a let’s-get-this-done approach is required. Cates goes further: “Even the ‘nasty boss approach’ can be really effective—but in short, small doses—to get everyone’s attention and say ‘Hey, we’ve got to make some changes around here.’ You can then create—with an earnest approach—that more likable persona as you move forward. Likability is a good thing to have in your leadership toolkit, but it shouldn’t be the biggest hammer in the box.”

Roddy Millar

I think there's a difference between 'trying to be likeable' and 'treating your colleagues with dignity and respect'.

If you're being nice to be just to liked by your team, you're probably doing it wrong. It's a bit like, back when I was teaching, teachers who wanted to be liked by the kids they taught.

The other approach is to simply treat the people around you with dignity and respect, realising that all of human life involves suffering, so let's not add to the burden through our everyday working lives.

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The above is one of my favourite quotations. We don't need to crack the whip or wield some kind of totem of hierarchical power over other people. We just need to ensure people are in the right place (physically and emotoinally), with the right things (tools, skills, and information) to get things done.

In managers are for caring, Harold Jarche points a finger at hierarchical organisations, stating that they are "what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator".

Jarche wonders instead what would happen if they were structured more like communities of practice?

What would an organization look like with looser hierarchies and stronger networks? A lot more human, retrieving some of the intimacy and cooperation of tribal groups. We already have other ways of organizing work. Orchestras are not teams, and neither are jazz ensembles. There may be teamwork on a theatre production but the cast is not a team. It is more like a community of practice, with strong and weak social ties.

Harold Jarche

I think part of the problem, to be honest, is emotional intelligence, or rather the lack of it, in many organisations.

Unfortunately, the way to earn more money in organisations is to start managing people. Which is fine for the subset of people who have the skills to be able to handle this. For others, it's a frustrating experience that takes them away from doing the work.

For TED Ideas, organisational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic asks Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? And what can we do about it? He lists three reasons why we have so many incompetent (male) leaders:

- Our inability to distinguish between confidence and competence

- Our love of charasmatic individuals

- The allure of “people with grandiose visions that tap into our own narcissism”

He suggests three ways to fix this. The other two are all well and good, but I just want to focus on the first solution he suggests:

The first solution is to follow the signs and look for the qualities that actually make people better leaders. There is a pathological mismatch between the attributes that seduce us in a leader and those that are needed to be an effective leader. If we want to improve the performance of our leaders, we should focus on the right traits. Instead of falling for people who are confident, narcissistic and charismatic, we should promote people because of competence, humility and integrity. Incidentally, this would also lead to a higher proportion of female than male leaders — large-scale scientific studies show that women score higher than men on measures of competence, humility and integrity. But the point is that we would significantly improve the quality of our leaders.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

The best leaders I've worked for exhibited high levels of emotional intelligence. Most of them were women.

Developing emotional intelligence is difficult and goodness knows I'm no expert. What I think we perhaps need to do is to remove our corporate dependency on hierarchy. In hierarchies, emotion and trust is removed as an impediment to action.

However, in my experience, hierarchy is inherently patriarchal and competitive. It's not something that's necessarily useful in every industry in the 21st century. And hierarchies are not places that I, and people like me, particularly thrive.

Instead, I think we require trust-based ways of organising — ways that emphasis human relationships. I think these are also more conducive to human flourishing.

Right now, approaches such as sociocracy take a while to get our collective heads around as they're opposed to our "default operating system" of hierarchy. However, over time I think we'll see versions of this becoming the norm, as it becomes ever easier to co-ordinate people at a distance.

To sum up, what it means to be an effective leader is changing. Returning to the article cited above by Harold Jarche, he writes:

Hierarchical teams are what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator. In a creative economy, the unity of hierarchical teams is counter-productive, as it shuts off opportunities for serendipity and innovation. In a complex and networked economy workers need more autonomy and managers should have less control.

Harold Jarche

Many people no longer live in a world of the 'permanent job' and 'career ladder'. What counts as success for them is not necessarily a steadily-increasing paycheck, but measures such as social justice or 'making a dent in the universe'. This is where hierarchy fails, and where emergent, emotionally-intelligent leaders with teams of self-organising ducks, thrive.

Friday foggings

I've been travelling this week, so I've had plenty of time to read and digest a whole range of articles. In fact, because of the luxury of that extra time, I decided to write some comments about each link, as well as the usual quotation.

Let me know what you think about this approach. I may not have the bandwidth to do it every week, but if it's useful, I'll try and prioritise it. As ever, particularly interested in hearing from supporters!

Education and Men without Work (National Affairs) — “Unlike the Great Depression, however, today's work crisis is not an unemployment crisis. Only a tiny fraction of workless American men nowadays are actually looking for employment. Instead we have witnessed a mass exodus of men from the workforce altogether. At this writing, nearly 7 million civilian non-institutionalized men between the ages of 25 and 54 are neither working nor looking for work — over four times as many as are formally unemployed.”

This article argues that the conventional wisdom, that men are out of work because of a lack of education, may be based on false assumptions. In fact, a major driver seems to be the number of men (more than 50% of working-age men, apparently) who live in child-free homes. What do these men end up doing with their time? Many of them are self-medicating with drugs and screens.

Fresh Cambridge Analytica leak ‘shows global manipulation is out of control’ (The Guardian) — “More than 100,000 documents relating to work in 68 countries that will lay bare the global infrastructure of an operation used to manipulate voters on “an industrial scale” are set to be released over the next months.”

Sadly, I think the response to these documents will be one of apathy. Due to the 24-hour news cycle and the stream of 'news' on social networks, the voting public grow tired of scandals and news stories that last for months and years.

Funding (Sussex Royals) — “The Sovereign Grant is the annual funding mechanism of the monarchy that covers the work of the Royal Family in support of HM The Queen including expenses to maintain official residences and workspaces. In this exchange, The Queen surrenders the revenue of the Crown Estate and in return, a portion of these public funds are granted to The Sovereign/The Queen for official expenditure.”

I don't think I need to restate my opinions on the Royal Family, privilege, and hierarchies / coercive power relationships of all shapes and sizes. However, as someone pointed out on Mastodon, this page by 'Harry and Meghan' is quietly subversive.

How to sell good ideas (New Statesman) — “It is true that [Malcolm] Gladwell sometimes presses his stories too militantly into the service of an overarching idea, and, at least in his books, can jam together materials too disparate to cohere (Poole referred to his “relentless montage”). The New Yorker essay, which constrains his itinerant curiosity, is where he does his finest work (the best of these are collected in 2009’s What The Dog Saw). For the most part, the work of his many imitators attests to how hard it is to do what he does. You have to be able to write lucid, propulsive prose capable of introducing complex ideas within a magnetic field of narrative. You have to leave your desk and talk to people (he never stopped being a reporter). Above all, you need to acquire an extraordinary eye for the overlooked story, the deceptively trivial incident, the minor genius. Gladwell shares the late Jonathan Miller’s belief that “it is in the negligible that the considerable is to be found”.”

A friend took me to see Gladwell when he was in Newcastle-upon-Tyne touring with 'What The Dog Saw'. Like the author of this article, I soon realised that Gladwell is selling something quite different to 'science' or 'facts'. And so long as you're OK with that, you can enjoy (as I do) his podcasts and books.

Just enough Internet: Why public service Internet should be a model of restraint (doteveryone) — “We have not yet done a good job of defining what good digital public service really looks like, of creating digital charters that match up to those of our great institutions, and it is these statements of values and ways of working – rather than any amount of shiny new technology – that will create essential building blocks for the public services of the future.”

While I attended the main MozFest weekend event, I missed the presentation and other events that happened earlier in the week. I definitely agree with the sentiment behind the transcript of this talk by Rachel Coldicutt. I'm just not sure it's specific enough to be useful in practice.

Places to go in 2020 (Marginal Revolution) — “Here is the mostly dull NYT list. Here is my personal list of recommendations for you, noting I have not been to all of the below, but I am in contact with many travelers and paw through a good deal of information."

This list by Tyler Cowen is really interesting. I haven't been to any of the places on this list, but I now really want to visit Eastern Bali and Baku in Azerbaijan.

Reasons not to scoff at ghosts, visions and near-death experiences (Aeon) — “Sure, the dangers of gullibility are evident enough in the tragedies caused by religious fanatics, medical quacks and ruthless politicians. And, granted, spiritual worldviews are not good for everybody. Faith in the ultimate benevolence of the cosmos will strike many as hopelessly irrational. Yet, a century on from James’s pragmatic philosophy and psychology of transformative experiences, it might be time to restore a balanced perspective, to acknowledge the damage that has been caused by stigma, misdiagnoses and mis- or overmedication of individuals reporting ‘weird’ experiences. One can be personally skeptical of the ultimate validity of mystical beliefs and leave properly theological questions strictly aside, yet still investigate the salutary and prophylactic potential of these phenomena.”

I'd happily read a full-length book on this subject, as it's a fascinating area. The tension between knowing that much/all of the phenomena is reducible to materiality and mechanics may explain what's going on, but it doesn't explain it away...

Surveillance Tech Is an Open Secret at CES 2020 (OneZero) — “Lowe offered one explanation for why these companies feel so comfortable marketing surveillance tech: He says that the genie can’t be put back in the bottle, so barring federal regulation that bans certain implementations, it’s increasingly likely that some company will fill the surveillance market. In other words, if Google isn’t going to work with the cops, Amazon will. And even if Amazon decides not to, smaller companies out of the spotlight still will.”

I suppose it should come as no surprise that, in this day and age, companies like Cyberlink, previously known for their PowerDVD software, have moved into the very profitable world of surveillance capitalism. What's going to stop its inexorable rise? I can only think of government regulation (with teeth).

‘Techlash’ Hits College Campuses (New York Times) — “Some recent graduates are taking their technical skills to smaller social impact groups instead of the biggest firms. Ms. Dogru said that some of her peers are pursuing jobs at start-ups focused on health, education and privacy. Ms. Harbour said Berkeley offers a networking event called Tech for Good, where alumni from purpose-driven groups like Code for America and Khan Academy share career opportunities.”

I'm not sure this is currently as big a 'movement' as suggested in the article, but I'm glad the wind is blowing in this direction. As with other ethically-dubious industries, companies involved in surveillance capitalism will have to pay people extraordinarily well to put aside their moral scruples.

Tradition is Smarter Than You Are (The Scholar's Stage) — “To extract resources from a population the state must be able to understand that population. The state needs to make the people and things it rules legible to agents of the government. Legibility means uniformity. States dream up uniform weights and measures, impress national languages and ID numbers on their people, and divvy the country up into land plots and administrative districts, all to make the realm legible to the powers that be. The problem is that not all important things can be made legible. Much of what makes a society successful is knowledge of the tacit sort: rarely articulated, messy, and from the outside looking in, purposeless. These are the first things lost in the quest for legibility. Traditions, small cultural differences, odd and distinctive lifeways... are all swept aside by a rationalizing state that preserves (or in many cases, imposes) only what it can be understood and manipulated from the 2,000 foot view. The result... are many of the greatest catastrophes of human history.”

One of the books that's been on my 'to-read' list for a while is 'Seeing Like a State', written by James C. Scott and referenced in this article. I'm no believer in tradition for the sake of it but, I have to say, that a lot of the superstitions of my maternal grandmother, and a lot of the rituals that come with religion are often very practical in nature.

Image by Michael Schlegel (via kottke.org)

Microcast #083 - Ambiguous in Kuwait City

Some reflections on my digital literacies pre-conference workshop yesterday for AMICAL.

Show notes

Given things as they are, how shall one individual live?

...asked Annie Dillard. It's a good question.

Richard D. Bartlett, who I support via Patreon and who is better known as richdecibels, has started a newsletter. The process of signing up for it reminded me of a post he wrote last year entitled Hierarchy Is Not The Problem...

Ten years ago, in my first foray into senior management, I was told by a consultant to the newly-installed Principal that "he's very hierarchical". She meant it in a good way, but I almost quit on the spot. To me, that's shorthand for a very dictatorial style of management.

So Bartlett's post, which I think I've mentioned before, is one I keep coming back to. He says that:

I don’t care about hierarchy. It’s just a shape. I care about power dynamics.

[...]

These days I have mostly removed “non-hierarchical” from my vocabulary. I still haven’t found a great replacement, but for now I say “decentralised”. But again, it’s not the shape that’s interesting, it’s the power dynamics.

Richard D. Bartlett

That's quite a challenging notion for me, having been in situations within very hierarchical organisations where people try and put me in a box, tie me to a particular role, or otherwise indicate I should stick to my own lane.

It's something I'm continue to process. I'm not sure whether Bartlett's correct. It's a great argument, and I've certainly seen some great organisations structured by way of what I'd call the "default operating system" of hierarchy.

Perhaps the thing is that it's easy to show the difference between the way an organisation is structured (its nodes) as opposed to the the difference between the way those nodes connect with one another. Interactions between other human beings are complicated, and difficult to put in a neat diagram.

Recently, Sam Altman, President of the famed startup accelerator Y Combinator, wrote a Twitter thread which he entitled How To Be Successful At Your Career. It's what people do instead of blogging these days, it would appear.

One tweet in the thread really stuck out to me, especially in this context of hierarchy and coercive power relationships:

The most successful people (judged by history, not money) continually look for the most important thing they are able to work on, and that’s what they do. They do not get trapped in local maxima, and they do not deceive themselves if they find something more important.

Sam Altman

In other words, what you're attempting to do should transcend the organisation you currently work for and the people with whom you currently work. I believe Steve Jobs called this "making a dent in the universe". It's unlikely to happen if you're playing politics within your organisation, if you're abusing a position of power, or you're spending all day in meetings.

Fred Wilson, a VC, says he often gets asked what to work on. This is understandable, given it's his job to keep his finger on the pulse of companies in which he can invest. Wilson sums up by saying:

You must work on something that inspires you and others, you must work on something with a significant impact, and you must do it in a way that makes getting where you want to go as easy as possible and keeps you there as long as possible.

Fred Wilson

I think this is a good mantra, and I appreciate that he doesn't just consider 'impact' to be 'financial impact', but also "how it changes the way people think and how they react to your product or service or innovation".

Context is really important. It's the reason why there is no one-size-fits-all approach to organisational structures, and why, unless you're the founder of the organisation, you will never be 100% aligned with everything it does. And even then, if your organisation grows to make an impact, there will be a difference between you and the organisation you helped to gestate.

All we can do, at any given point, is to weigh up where we are, using principles such as Fred Wilson's:

- Am I working on something that inspires me (and others)?

- Am I working on something with a significant impact?

- Am I working in a way that makes getting where I want to go as easy as possible (and keeps me there as long as possible)?

As Altman writes, that's likely to be in a place that doesn't play politics and, to Bartlett's point, it's important to pay very close attention to power dynamics. In short, it's important to ask ourselves regularly, "Am I best positioned to make the particular dent I've decided to make in the universe?"

Friday flurries

It's been a busy week, but I've still found time to unearth these gems...