100% inheritance tax?

If we can’t stop people raking up ridiculous sums of money, we can definitely prevent them passing on that wealth to their kids. Thankfully, more enlightened rich people (in this case actor Daniel Craig) are already putting their own measures in place.

In a Hollywood interview published this week in Candis magazine, Mr Craig made reference to Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish-born US industrialist and one of the wealthiest men in history.Source: ‘Inheritance is distasteful’: Daniel Craig’s children will not be getting his Bond millions | The Telegraph“Isn’t there an old adage that if you die a rich person, you’ve failed?” he said. “I think Andrew Carnegie gave away what in today’s money would be about $11 billion, which shows how rich he was because I’ll bet he kept some of it too.“

But I don’t want to leave great sums to the next generation. I think inheritance is quite distasteful. My philosophy is: get rid of it or give it away before you go."

Culture is in a state of constant flux

My parents, the son of a factory worker and assistant baker and the daughter of domestic servants, were both the first in their families to go to university. As such, they wanted to ensure that their children, my sister and I, knew our way around ‘culture’.

Hence, for me, a childhood punctuated not only piano lessons and visits to National Trust properties but visits to the cheapest seats at the theatre to see ballets and plays. In their mind, at least back then, there was ‘Culture’ (with a capital ‘C’) to which we had to be introduced.

As Kojo Koram from the School of Law at Birkbeck, University of London, writes, however, culture is something that is continually remade by the people living it. These different conceptions mark the boundaries of the culture wars currently being played out in British politics and society.

In the 1960s and 70s, when [Stuart] Hall was writing, most British intellectuals dismissed the new mass culture taking hold in the country as a passing fad that did not deserve the attention given to Shakespeare, Elgar or Hogarth. But Hall recognised how it offered an increasingly multicultural British population the opportunity to interpret and experience life as it was lived on the ground. Rather than seeing culture as something fixed and unchanging that needed constant protection, Hall saw it as something that underwent “constant transformation” and was always being made and remade by the people living it, a moving force that perpetually created new identities.Source: Here’s what the right gets wrong about culture: it’s not a monument, but a living thing | The GuardianIt is no coincidence that so many of the primary battlegrounds where today’s culture wars are being staged are the elite institutions that represent a traditional British hierarchy: stately homes, Oxford university common rooms, the Last Night of the Proms. To culture warriors on the right, these institutions best represent Britain’s national culture as a whole. That they are exclusive is part of their appeal: when culture is defined as something that only a few people can access or control, its preservation is best entrusted to high-ranking authorities.

The Great Reckoning

When I was a teacher and school senior leader in my twenties I worked all the hours. Not only that, but I was writing my doctoral thesis and we had a young baby. I’ve never worked so hard or be so close to burnout.

Since switching to being based from a home office in 2012 my life has been transformed. With no commute and no planning, preparation, and assessment, I’m paid for the time I actually work. And since 2017 and setting up a co-op, I’m jointly in charge of the means of production as well.

As Cal Newport writes in The New Yorker, others are cottoning-on to these advantages since the pandemic, leading to a wave of resignations.

These people are generally well-educated workers who are leaving their jobs not because the pandemic created obstacles to their employment but, at least in part, because it nudged them to rethink the role of work in their lives altogether. Many are embracing career downsizing, voluntarily reducing their work hours to emphasize other aspects of life.Words

Many well-compensated but burnt-out knowledge workers have long felt that their internal ledger books were out of balance: they worked long hours, they made good money, they had lots of stuff, they were exhausted, and, above all, they saw no easy options for changing their circumstances. Then came shelter-in-place orders and shuttered office buildings. This particular class of workers were thrown into their own Zoom-equipped versions of Walden Pond. Diversion and entertainment were stripped down to basic forms, and it became difficult to spend more than the cost of a Netflix subscription or batch of sourdough starter to keep occupied. The absence of visits with friends and family reinforced the value of social connection. The unceasing presence of video conferencing and e-mail enhanced the Kafkaesque superfluousness of many of the activities that dominated the pre-pandemic workday. This class of workers was suddenly staring at the proverbial cabin and wondering if a copper pump would really be worth the labor required to cultivate another acre.Source: Why Are So Many Knowledge Workers Quitting? | The New Yorker

Brains melted like butter in a microwave

This is a really powerful essay about the American response — or lack of it to the news that the Taliban have taken Kabul. The author, Antonio García Martínez, contends that Americans are “no longer a serious people” and spend too much time manufacturing reality.

You see, in the Before Times there was a reality ‘out there’, peoples and cultures unlike ours that stubbornly refused to think and act as we did (and we knew it); facts on the ground that were immune to social-media spirals of bloviation and simply could not be ignored (and we knew it). We grappled with them, debated them, rallied consensus around them, and just dealt with reality however poorly perceived it might have been. And leaders who could not deal with inarguable realities, such as Carter with his botched Iranian rescue operation, did not stay leaders for very long.The war in Afghanistan cost a trillion dollars over 20 years, thousands of lives, and was ultimately an exercise in futility:

This might seem flip and 'too soon', but the irony highlights the real civilizational difference here: one where combat is via prissy morality and pure spectacle, and one where the battles are literal and deadly. One where elites contest power via spiraling purity and virality contests waged online, and where defeat means ‘cancelation’ or livestreamed ‘struggle sessions’ around often imaginary or minor offenses. And another place where the price of defeat is death, exile, rape, destitution, and fates so grim people die dangling from airplanes in order to escape.Source: We are no longer a serious people | The Pull RequestIn short, an unserious country mired in the most masturbatory hysterics over bullshit dramas waged war against an insurgency of religious zealots fired by a 7th-century morality, and utterly and totally lost.

And all we can do in the wake of it, with our brains melted like butter in a microwave by four years of Trump and Twitter and everything else, is to once again try and understand in our terms a hyper-violent insurgency of fanatics, guilty of every manner of cultural barbarism, now running a country with the population of Texas.

What is 'solarpunk'?

I've seen people on the Fediverse, including people I know and have worked with, describe themselves as 'solarpunks'. It seems like the approach is becoming more mainstream, which is no bad thing.

Lush green communities with roof top gardens, floating villages, transport fuelled by clean energy and hope-filled sci-fi tales. Imagine a world in which existing technologies are deployed for the greater good of both people and the planet.

It's called solarpunk. The term, coined in 2008, refers to an art movement which broadly envisions how the future might look if we lived in harmony with nature in a sustainable and egalitarian world.

"Solarpunk is really the only solution to the existential corner of climate disaster we have backed ourselves into as a species," says Michelle Tulumello, a solarpunk art teacher in New York state.

"If we wish to survive and keep some of the things we care about on the earth with us, it involves a necessary fundamental alteration in our world view where we change our outlook completely from competitive to cooperative."

Source: What is solarpunk and can it help save the planet? | BBC News

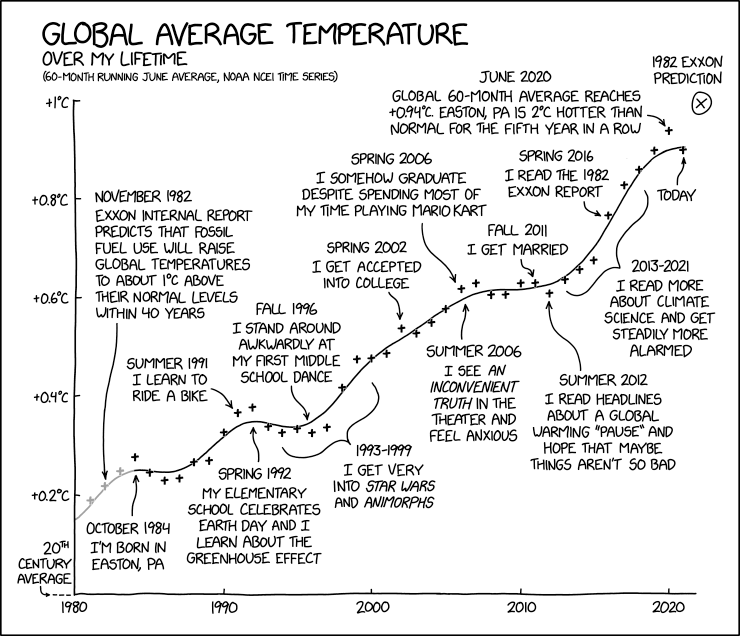

Global temperatures: 1980-2021

This xkcd chart starts in 1980 which is when I was born so, although it has Randall Munroe’s details on it, in some ways it also feels personal to me.

Five-hour workdays

I’ve been saying for as long as anyone will listen to me that I can do a maximum of four hours high-quality knowledge work per day. Add on some time for emails and ‘sync’ meetings, and five seems about right.

The difficulty, of course, is the financial side of things. If you’re employed, will your employer pay you the same amount for working fewer hours? (even if productivity increases). And if you’re self-employed, will clients sign-off contracts that stipulate five-hour days?

The eight-hour working day is a relatively new concept, widely accepted to have been cemented by Ford Motor Company a century ago as a means of keeping production going 24 hours a day without putting undue demands on individual members of staff. Ford’s experiment led to an increase in overall productivity; but proponents of five-hour days, including Californian ecommerce business Tower Paddle Boards and German digital consultancy Rheingans, say they experienced a similar phenomenon when they moved to compressed-hour models.Source: The perfect number of hours to work every day? Five | WIREDLike Corcoran, Tower CEO Stephan Aarstol says he was startled by the results when the business adopted a five-hour working day in 2015. Staff worked from 8am to 1pm with no breaks and, because employees became so focused on maximising output in order to have the afternoons to themselves, turnover increased by 50 per cent.

The Cult of the Upper Classes

Today is the day that the IPCC report is released. Our response to it, in the UK at least, depends a great deal on the attitude that the upper classes have towards it. That shouldn’t be the case.

Far too many people in this country remain wedded to the cult of the upper class – a cult that should long ago have withered to a death, but which is instead enabled by the media, by stealth, and by a fawning faith in aristocracy that still prevails. Its bastard by-product, nepotism, remains rife – elevating those of little talent, charm or ability to some of the top gigs in the land.Source: England’s Upper Classes: A Dangerous Cult – Byline Times

The Cult of the Upper Classes

Today is the day that the IPCC report is released. Our response to it, in the UK at least, depends a great deal on the attitude that the upper classes have towards it. That shouldn’t be the case.

Far too many people in this country remain wedded to the cult of the upper class – a cult that should long ago have withered to a death, but which is instead enabled by the media, by stealth, and by a fawning faith in aristocracy that still prevails. Its bastard by-product, nepotism, remains rife – elevating those of little talent, charm or ability to some of the top gigs in the land.Source: England’s Upper Classes: A Dangerous Cult – Byline Times

Internal Google comics

I discovered these comics, made over several years by someone who worked at Google, via Hacker News. The one below I thought was a fantastic roast of the kind of 'leadership' I've seen at a few organisations.

Source: Goomics

5 main concerns of top scientists about the relaxing of UK Covid restrictions

This warning to the UK government with the ‘five main concerns’ of top scientists is quite concerning.

First, unmitigated transmission will disproportionately affect unvaccinated children and young people who have already suffered greatly. Official UK Government data show that as of July 4, 2021, 51% of the total UK population have been fully vaccinated and 68% have been partially vaccinated. Even assuming that approximately 20% of unvaccinated people are protected by previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, this still leaves more than 17 million people with no protection against COVID-19. Given this, and the high transmissibility of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, exponential growth will probably continue until millions more people are infected, leaving hundreds of thousands of people with long-term illness and disability. This strategy risks creating a generation left with chronic health problems and disability, the personal and economic impacts of which might be felt for decades to come.Source: Mass infection is not an option: we must do more to protect our young | The LancetSecond, high rates of transmission in schools and in children will lead to significant educational disruption, a problem not addressed by abandoning isolation of exposed children (which is done on the basis of imperfect daily rapid tests). The root cause of educational disruption is transmission, not isolation. Strict mitigations in schools alongside measures to keep community transmission low and eventual vaccination of children will ensure children can remain in schools safely This is all the more important for clinically and socially vulnerable children. Allowing transmission to continue over the summer will create a reservoir of infection, which will probably accelerate spread when schools and universities re-open in autumn.

Third, preliminary modelling data9 suggest the government’s strategy provides fertile ground for the emergence of vaccine-resistant variants. This would place all at risk, including those already vaccinated, within the UK and globally. While vaccines can be updated, this requires time and resources, leaving many exposed in the interim. Spread of potentially more transmissible escape variants would disproportionately affect the most disadvantaged in our country and other countries with poor access to vaccines.

Fourth, this strategy will have a significant impact on health services and exhausted health-care staff who have not yet recovered from previous infection waves. The link between cases and hospital admissions has not been broken, and rising case numbers will inevitably lead to increased hospital admissions, applying further pressure at a time when millions of people are waiting for medical procedures and routine care.

Fifth, as deprived communities are more exposed to and more at risk from COVID-19, these policies will continue to disproportionately affect the most vulnerable and marginalised, deepening inequalities.

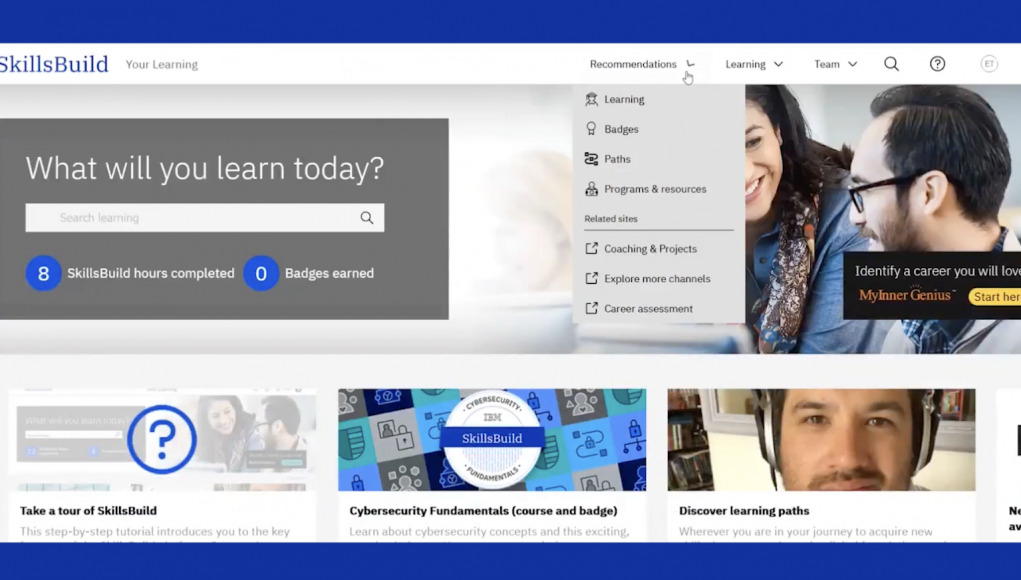

Skills-based hiring vs universities

This is Stephen Downes' commentary on an article by Tom Vander Ark. I think crunch time is coming for universities, especially when you think about how people are increasingly applying for jobs with portfolios, microcredentials, and proof of experience, rather than simply a CV with a degree on it.

Educators need to be aware that the marketing campaign against their unique value proposition is well underway. "Companies are missing out on skilled, diverse talent when they arbitrarily ‘require’ a four-year degree. It’s bad for workers and it’s bad for business. It doesn’t have to be this way," says former McKinsey partner Byron Auguste, who founded Opportunity@Work. "Instead of ‘screening out’ by pedigree, smart employers are increasing ‘screening in talent for performance and potential." The question for colleges and universities is this: if people no longer value your degrees and certificates, what will you be selling them when you charge them tuition fees?Source: The Rise of Skills-Based Hiring And What it Means for Education | Stephen Downes

Mr Bingo's Zoom backgrounds

This made me laugh, especially as in the midst of the pandemic I was using a green screen and changing my Zoom background every day!

<img src=“uploads/2024/4b04687167.jpg” alt=“Stretched letters saying “Zoom is destroying my soul” />

Source: Zoom backgrounds | Mr Bingo: Artist, speaker and twat

On Twitter addiction

I used to be addicted to Twitter before it was cool to be addicted to Twitter. Back when all you got was 140 characters, and I’d find myself composing tweets about my IRL experiences and find that I was basically thinking in tweet-sized chunks.

I’ve since switched most of my attention to the Fediverse (join me?) but there’s something insidious about Twitter that pulls you back in. At least turning off the algorithmic timeline (something you have to keep doing) dials down the rage a little bit…

I know I’m an addict because Twitter hacked itself so deep into my circuitry that it interrupted the very formation of my thoughts. Twenty years of journalism taught me to hit a word count almost without checking the numbers at the bottom of the screen. But now a corporation that operates against my best interests has me thinking in 280 characters. Every thought, every experience, seems to be reducible to this haiku, and my mind is instantly engaged by the challenge of concision. Once the line is formed, why not put it out there? Twitter is a red light, blinking, blinking, blinking, destroying my ability for private thought, sucking up all my talent and wit. Put it out there, post it, see how it does. What pours out is an ungodly sluice of high-minded opinions, sharp rebukes, jokes, transactional compliments, and mundane bulletins from my private life (to the extent that I have one anymore).Source: A Twitter Addict Realizes She Needs Rehab | The Atlantic

Propeller-based car that can go faster than the wind

This is pretty amazing.

[embed]www.youtube.com/watch

Source: A Physics Prof Bet Me $10,000 I’m Wrong | Veritasium

Main-Character Energy

Before starting therapy, my wife said that she was concerned that I might “lose my superpowers”. One of the ways of thinking about this is as the Main-Character Energy discussed in this New Yorker article. It’s a vitality you bring to each day because you see yourself in a starring role.

Therapy did strip me of that, but in a good way. Instead of some Hollywood actor, I now see myself in a much more realistic light, rather in the way that social media can distort and mediate the view I have of myself. It means that I see myself a part of a whole, rather than set apart from it.

The impulse to see oneself as the focal point of the action is all the more powerful as we emerge from the dull isolation of the pandemic, when activities were limited to the likes of re-growing scallions and feeding bulbous sourdough starters. Post-covid, we want to reclaim control of our stories, exert ourselves upon the world, take our places as protagonists once more—and then post about it. During quarantine, the Internet was one of the few tethers to public connection. But publishing evidence of any social engagements, even C.D.C.-compliant ones, came with the risk of being shamed as reckless or self-indulgent. Now, suddenly, much of that fear of critique is gone. The “return of fomo,” as a recent New York cover described it, means the return of jealousy-inducing Instagram stories and glamorous TikToks.Source: We All Have “Main-Character Energy” Now | The New Yorker

Parasocial relationships through digital media

I think we’ve all felt a close affinity and, dare I say, relationship with people who wouldn’t know who we were if we met them in real life. In fact, I’ve kind of experienced the other side of this due to my TEDx Talk and the TIDE podcast. People at events would come and talk to me as if they knew me.

It’s nice, in a way, although it makes for very one-sided conversations until you get to know people. I think it’s likely to happen again with the Tao of WAO podcast…

Over the past decade, it has become increasingly common for people to develop intense one-sided relationships with famous people on the internet. What are called parasocial relationships (meaning almost social, or perversely social) have spread almost everywhere. For example, John Mulaney fans share concern over his recently messy personal life as much as they laugh at his jokes. Fans of K-pop groups like Blackpink (called Blinks) and Twice (called Onces) flood YouTube videos with millions of comments in support of their favorite performers. (“Rosé has worked so hard for this moment, let’s support her as much as we can!!”) Zoomers goof off in the chat for hours watching Twitch livestreamers play Minecraft or PUBG. Even Peloton trainers are marketed as supporting us on our fitness journeys rather than coaches who simply encourage us to sweat.Source: Why Can’t We Be Friends | Real LifeThe hosts of podcasts in particular are the subject of these intense feelings of connection, as many observers, like Rachel Aroesti in this Guardian piece for instance, have pointed out. I have a few parasocial podcast obsessions myself, particularly the podcasting family the McElroy Brothers, who make the comedy advice show My Brother, My Brother and Me and the “actual play” Dungeons and Dragons podcast The Adventure Zone, among other things. I follow fan subreddits, chuckle at McElroy memes, and buy merch to support the good good boys (as they are called). I have become as much a fan of the McElroys “themselves” as I am a fan of their content. I know their childhood nicknames, their struggles with depression and social anxiety, and I know about the time Justin got fired from Blockbuster for stealing a Fight Club DVD.

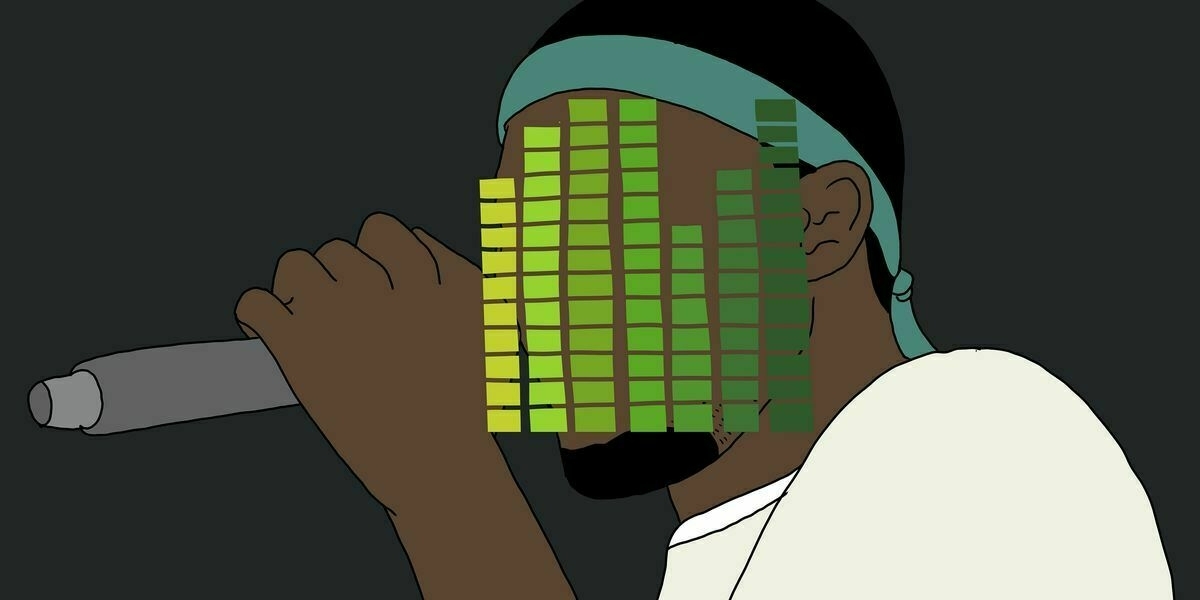

The album is no longer the unit of musical currency

I’m sitting listening to the new Kings of Convenience album while writing this. As this article points out, listening to albums is an increasingly unlikely thing to in the era of streaming music services.

This isn’t accidental: it’s easy to hop between services when the unit of currency is an ‘album’. But when it’s a regularly-updated playlist that’s only available on a particular platform (e.g. Spotify) that’s a different proposition altogether.

To help listeners find their way in the endless aisles of digital music, streaming providers created playlists — but this new way of listening has created unintended consequences for artists and songwriters. Today, three services make up two-thirds of the streaming economy: Spotify, which has an estimated 32 percent of the market, Apple Music (18 percent), and Amazon Music (14 percent). But Spotify dominates the conversation both because of its market power and its immensely popular playlists. In 2017, 68 percent of all listening on Spotify was from a company or user playlist, according to the company’s 2018 Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Its platform has more than 4 billion playlists, 3,000 of which are owned by Spotify, curated by a mix of algorithms and editors.Source: How streaming made hit songs more important than the pop stars who sing them | VoxIts most prominent playlists have serious cultural power. RapCaviar shapes the sound of hip-hop, and can turn indie rappers into household names. The genre-agnostic, slightly quirky playlist Lorem curates the vibe for Spotify’s Gen Z listeners. In 2020, listeners ages 16 to 40 used playlists as their primary source for discovering new music on the platform, according to the company. So today, a placement atop one of its playlists can make or break a song.

Spotify isn’t shy about the marketing power of its playlists. In its SEC filing, the company wrote as much, crediting Lorde’s breakout global success to her placement on a single playlist: Sean Parker’s Hipster International. But her example may be an outlier. The challenge for most artists is that playlist listeners frequently don’t know who they’re listening to. A song with high completion rates on a playlist might end up on more playlists, accumulating millions of streams for an artist who remains effectively nameless. In the best-case scenario, these streams, which pay very low royalties compared to radio, could help land the song a coveted advertisement, or better yet, pique the attention of Top 40 radio programmers.

Leslie Caron on Cary Grant's attitude to money

I read most things online, but I came across this one via my print subscription to Guardian Weekly (which I recommend highly). Leslie Caron, who danced and acted with a host of big names, highlights Cary Grant’s attitude towards money.

I’ve always found Cary Grant fascinating, and in fact my online avatar used to be a photo of him. It seems, as Leslie Caron points out, that one’s mindset can be out of step with reality — which is a lesson to us all.

Who was her most talented leading man? “Cary Grant,” she answers immediately. In 1964, she starred with Grant in the romcom Father Goose; Grant was 27 years her senior. “Cary was a complicated brain,” she says, pointing to her head. “He was a remarkable performer. He was very instinctive, seductive, intelligent. But when he got mad he would get into a terrible state. He worried about money.” Surely he had plenty of it? Yes, she says, but when you grow up poor you always think like a poor person. “I remember Charlie Chaplin saying to me: ‘If I were rich …’” When Chaplin died in 1977, he left more than $100m to his fourth wife, Oona.Source: ‘I am very shy. It’s amazing I became a movie star’: Leslie Caron at 90 on love, art and addiction | The Guardian

Hemp captures more carbon than trees

I don’t think it will be long before we see fields and fields of hemp, just like we see fields of rapeseed at the moment. For example, I often wear hemp t-shirts which need to be washed way less than cotton ones.

Shah is working with the farm to develop new carbon-negative materials that could be used in manufacturing and construction."Source: Hemp “more effective than trees” at carbon storage says researcher | DezeenWith Margent Farm’s hemp fibres, and using 100 per cent bio-based resins, we can produce bioplastics that can replace fibreglass composites, aluminium and other materials in a range of applications," he said."

We can use the wealth of textile science knowledge that humans have gathered over thousands of years to produce a range of textile fibre composites with properties suitable for non-structural products."

Shah added that the plant has the potential to help solve a wide variety of issues."

Hemp is a terrific crop that enables us to tackle a multitude of human-generated environmental problems – air, soil and water for example – whilst being productive in offering us food, medicine and materials," he said.