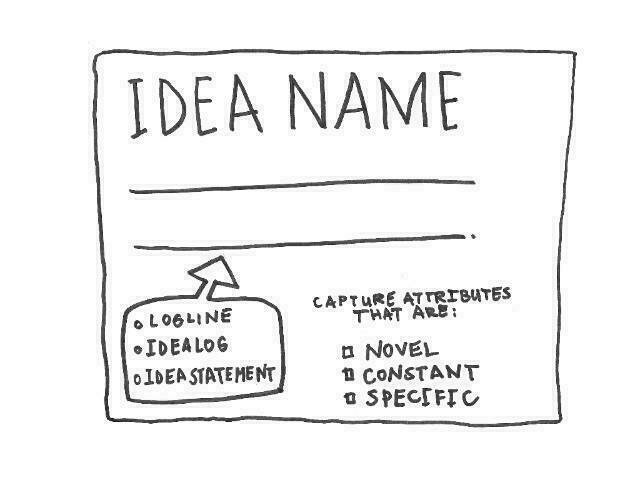

Explaining ideas

This comes at things from a branding/advertising perspective, but I appreciate the focus on clarity of language. After all, clarity of language is clarity of thought.

Ideas are thoughts but not all thoughts are “ideas.” Here’s an example of the use of the word “idea” in an agency setting: “I have an idea — let’s do something with augmented reality or Blockchain or make a special lens.” This isn’t wrong; it’s sloppy.Source: How to explain an idea: a mega post | Mark PollardIn the traditional industry sense, “idea” means a novel concept. But when it’s used as in this example, it masks the lack of an actual idea — like when someone dumps in the word “strategic” before they say something that’s not strategic. It ups the importance of what comes next. The problem: sometimes this works as a meeting tactic but does not lead to good or clear thinking.

Compare this thought with the use of the word “idea” as a novel concept: “I have an idea — I want to create a tool that runners can use to track how far they’ve run and then compete with each other by sharing their achievements via the Internet. They’ll track it via this technology in their shoe which will talk to their computer.”

BBC Archives and the changing of history

On the one hand, I’m glad that the BBC is ensuring that some of its archive material is a bit more in keeping with our (hopefully more enlightened) sensibilities.

However, on the other hand, why do this in secret?

“The sinister fact about literary censorship in England,” Orwell wrote back in 1945, “is that it is largely voluntary.” And so, indeed, it is. Over the weekend, the Daily Telegraph reported that “an anonymous Radio 4 Extra listener” had “discovered the BBC had been quietly editing repeats of shows over the past few years to be more in keeping with social mores.” To which the BBC said . . . well, yeah. In a statement addressing the charge, the institution confirmed that “on occasion we edit some episodes so they’re suitable for broadcast today, including removing racially offensive language and stereotypes from decades ago, as the vast majority of our audience would expect.” Thus, in the absence of law or regulation, has the British establishment begun to excise material it finds inappropriate by today’s lights.Source: BBC Censors Its Own Archives | National Review[…]

This raises a host of important questions — chief among which is: Why, if “the vast majority” of the BBC’s audience expects the organization to render its archives more “suitable,” has it been doing so in secret? Again: In the Internet age, changes made to source material tend to be iterative rather than additive. When the New York Times updates a story in its newspaper, one can plausibly obtain both copies. By contrast, when the New York Times updates a story on its website, the original page disappears. By its own admission, the BBC has been deleting entire sketches from comedy series that are 50, 60, or 70 years old, many of which can be heard only with the BBC’s permission. Are we simply to assume that the public supports this development? And, if so, are we permitted to wonder why the BBC was not open about it?

Private schools having charitable status is an absolute scam

I’ve always been against private schooling. I’m glad that others, even those who went to them themselves, are also seeing how bad they are for society.

I hate the new trend of British private schools opening branches abroad because the reason, it seems to me, is naked and unreflecting expansionism. It’s not spreading the original institution’s educational values because, as the Times investigation shows, they’re all too ready to drop those values in order to continue to trade. The desire for revenue obviously plays a part but, as the institutions don’t make profits, I don’t think personal financial rewards for the various executive headteachers or boards of governors are a huge factor. It’s less intelligent than that. It comes from an ill-considered capitalistic urge for growth, nothing more thought through than bigger is better.Source: Expansionist private schools need a lesson in morality | David Mitchell | The GuardianThis is the same reason McDonald’s opened a branch in Soviet Moscow, but that was fine because, as far as I know, McDonald’s has never applied for charitable status. What is astonishing is how, by conducting themselves in this way, private schools seem to have given up on making a meaningful argument to retain that status themselves. They’ve just stopped caring about the views of the likes of me. Is the right wing of the Conservative party now so completely dominant that the idea of keeping the sympathy of anyone on the left or in the centre feels like a waste of time?

Your attention was stolen

I still find it hard to trust Johann Hari’s writing, but this is more introspective and covers a subject that we all know is an issue: attention.

For me, despite being ‘verified’ on Twitter and having what used to be considered a decent number of followers, I’ve deactivated my account. I think it’s for the last time. I’m so much calmer when not using it.

I realised that to heal my attention, it was not enough simply to strip out distractions. That makes you feel good at first – but then it creates a vacuum where all the noise was. I realised I had to fill the vacuum. To do that, I started to think a lot about an area of psychology I had learned about years before – the science of flow states. Almost everyone reading this will have experienced a flow state at some point. It’s when you are doing something meaningful to you, and you really get into it, and time falls away, and your ego seems to vanish, and you find yourself focusing deeply and effortlessly. Flow is the deepest form of attention human beings can offer. But how do we get there?Source: Your attention didn’t collapse. It was stolen | The Guardian

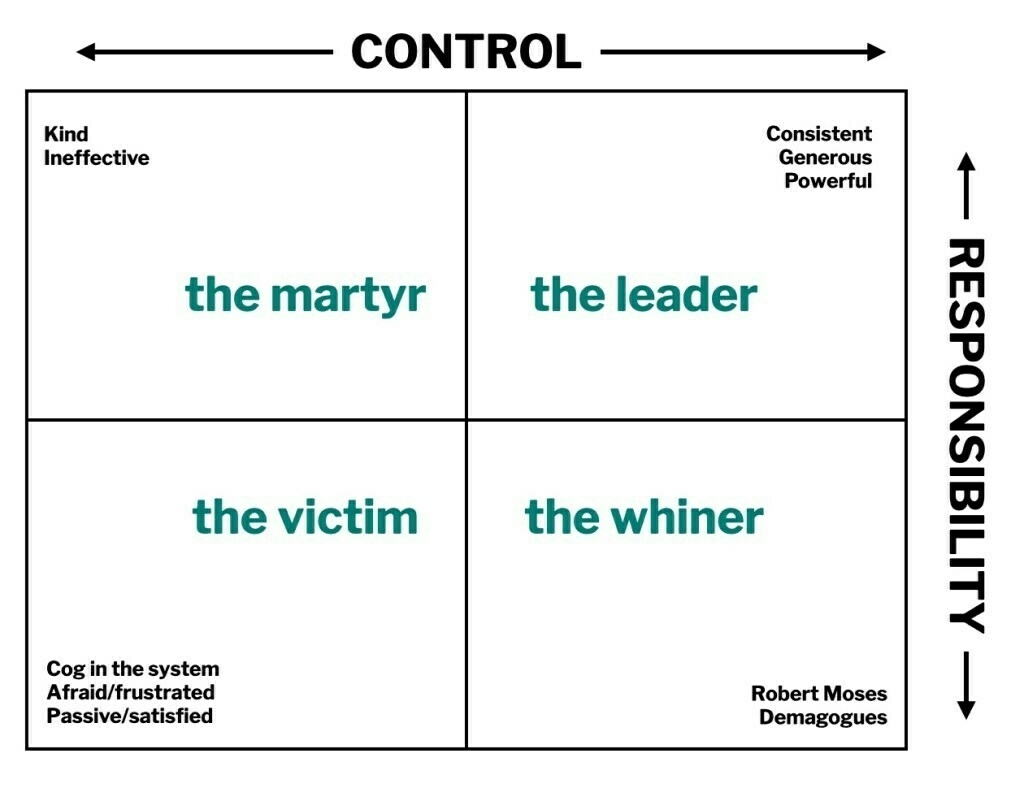

Control and responsibility

A massive over-simplification, but then that’s the point of 2x2 grids. Of course, everyone wants to think they’re in the top-right corner…

In many situations, we have the freedom to choose. We can choose a quadrant or we can choose not to participate. And if we’re lucky or care enough, we can choose who to vote for, who to work for and where we’re headed.Source: The control/responsibility matrix | Seth's Blog

Spatial Finance

Using real-time satellite imagery to ensure that people are building (or not-building) what they say they’re going to.

‘Spatial finance’ is the integration of geospatial data and analysis into financial theory and practice. Earth observation and remote sensing combined with machine learning have the potential to transform the availability of information in our financial system. It will allow financial markets to better measure and manage climate-related risks, as well as a vast range of other factors that affect risk and return in different asset classes.Source: Spatial Finance Initiative - Greening Finance and Investment

Health surveillance

It’s possible to be entirely in favour mass vaccination (as I am) while also concerned about the over-reach of states with our personal health data.

As this article discusses, based on a report from an German non-profit called AlgorithmWatch, such health surveillance is being normalised due to the requirements of responding to a global pandemic.

The idea that technology can be used to solve complex social issues, including public health, is not a new one. But the pandemic strongly influenced how technology is applied, with much of the push coming from public health policymaking and public perceptions, said the report.Source: Pandemic Exploited To Normalise Mass Surveillance? | The ASEAN PostThe report also highlighted the growing divide between people who fervently defend the schemes and those who staunchly oppose them - and how fear and misinformation have influenced both sides.

NFTs, financialisation, and crypto grifters

At over two hours long, I’m still only half-way through this video but I can already highly recommend it. There’s some technical language, as befits the nature of what’s discussed, but I really appreciate it going right back to the financial crisis to explain what’s going on.

[embed]www.youtube.com/watch

Source: The Problem With NFTs | YouTube

Tether and crypto price manipulation

You’d expect Jacobin to be against crypto, but this is the first level-headed explanation of the ‘Tether controversy’ I’ve seen.

There is no conceivable universe in which cryptocurrency exchanges should need an exponentially expanding supply of stablecoins to facilitate daily trading. The explosion in stablecoins and the suspicious timing of market buys outlined in the 2017 paper suggest — as a 2019 class-action lawsuit alleges — that iFinex, the parent company of Tether and Bitfinex, is printing tethers from thin air and using them to buy up Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies in order to create artificial scarcity and drive prices higher.Source: Cryptocurrency Is a Giant Ponzi Scheme | JacobinTether has effectively become the central bank of crypto. Like central banks, they ensure liquidity in the market and even engage in quantitative easing — the practice of central banks buying up financial assets in order to stimulate the economy and stabilize financial markets. The difference is that central banks, at least in theory, operate in the public good and try to maintain healthy levels of inflation that encourage capital investment. By comparison, private companies issuing stablecoins are indiscriminately inflating cryptocurrency prices so that they can be dumped on unsuspecting investors.

This renders cryptocurrency not merely a bad investment or speculative bubble but something more akin to a decentralized Ponzi scheme. New investors are being lured in under the pretense that speculation is driving prices when market manipulation is doing the heavy lifting.

This can’t go on forever. Unbacked stablecoins can and are being used to inflate the “spot price” — the latest trading price — of cryptocurrencies to levels totally disconnected from reality. But the electricity costs of running and securing blockchains is very real. If cryptocurrency markets cannot keep luring in enough new money to cover the growing costs of mining, the scheme will become unworkable and financially insolvent.

No one knows exactly how this would shake out, but we know that investors will never be able to realize the gains they have made on paper. The cryptocurrency market’s oft-touted $2 trillion market cap, calculated by multiplying existing coins by the latest spot price, is a meaningless figure. Nowhere near that much has actually been invested into cryptocurrencies, and nowhere near that much will ever come out of them.

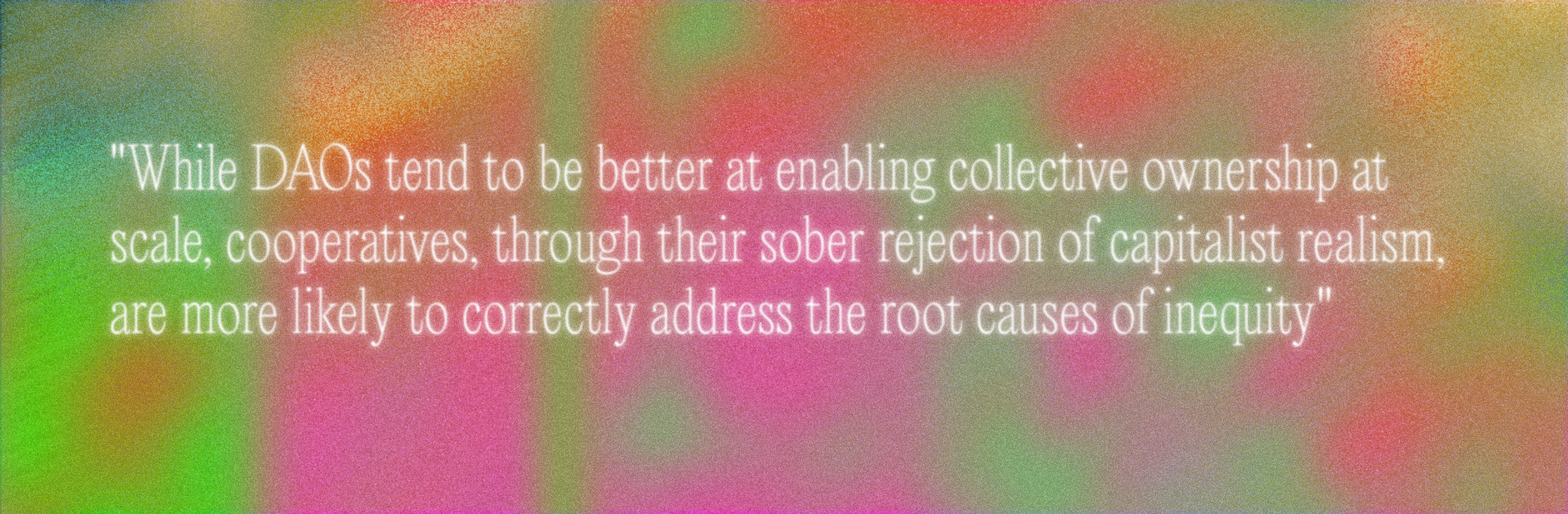

Co-ops and DAOs

Handy article, especially for those deep in the ‘capitalist realism’ (or neoliberalism) that the author describes.

Although co-ops and DAOS are both collectively owned and co-determined organizational forms, there are some key differences. Primarily, cooperatives have one-member, one-vote governance. This means that people vote, not dollars. No single member of a cooperative can purchase more power than anyone else.Source: What Co-ops and DAOs Can Learn From Each OtherWhile it is possible for DAOs to emulate cooperative governance, it’s more common to observe the easier-to-implement governance pattern of one-token, one-vote, since verifying one’s personhood is still a nascent field in the world of blockchain.

[…]

From my experiences in the two spaces, I have noticed that DAOs tend to be better at enabling collective ownership at scale, even if their cultural understanding of the rights, responsibilities, and accountability associated with ownership is comparatively underdeveloped. And while cooperatives tend to be less successful in securing funding, they are also more likely, through their sober rejection of capitalist realism, to correctly address the root causes of inequity. Below, I’ll share some of the key takeaways I have gleaned about what DAOs and co-ops can learn from each other.

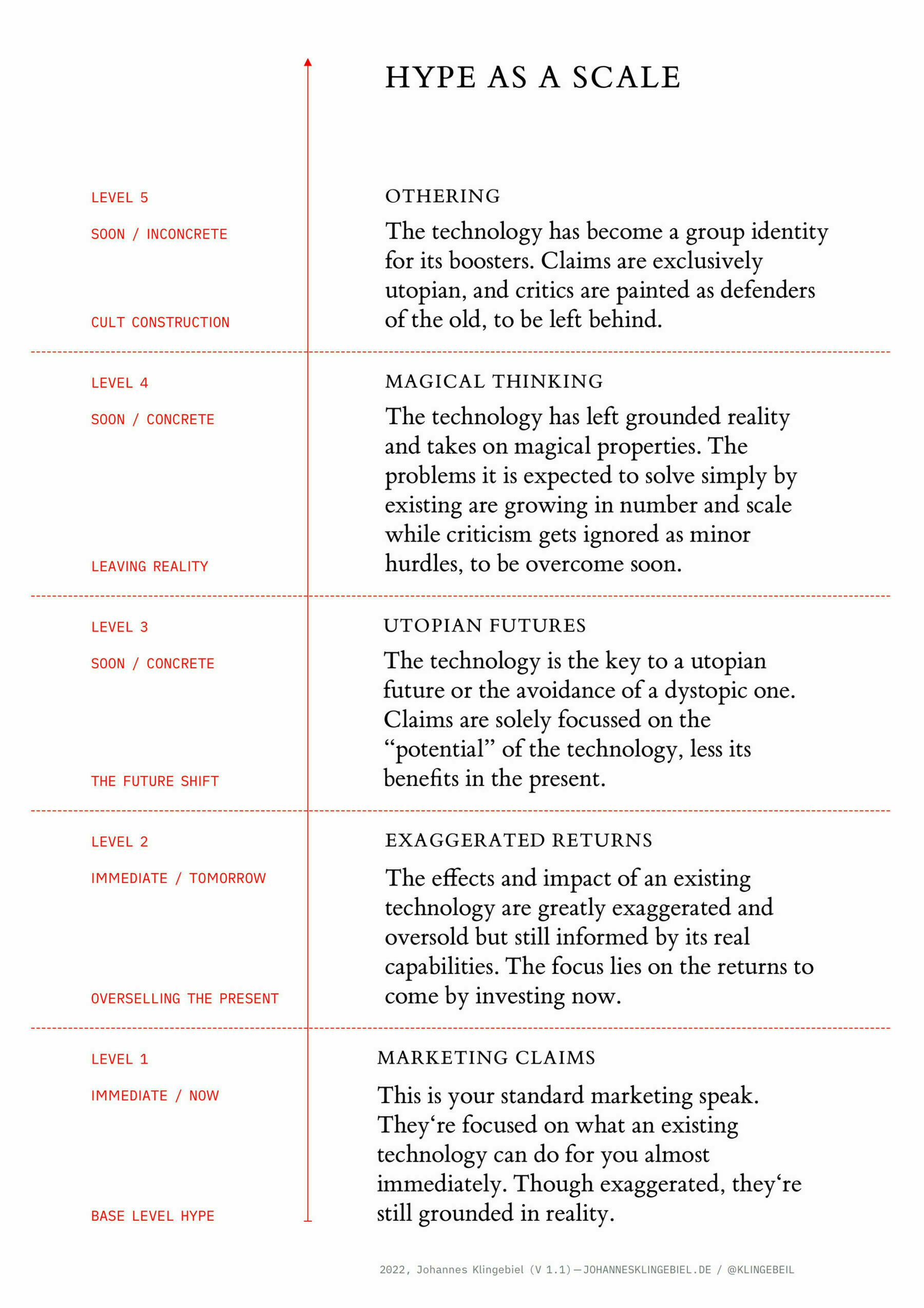

Hype levels

Handy. I do like typologies and scales.

Today‘s tech industry is obsessed with the big futures. The metaverses, the next internets — you name it. Hype is everywhere, oozing out of the headlines of news articles, growing like mold all over my LinkedIn feed, and blinking at me whenever I open my inbox.Source: The five Levels of Hype | Johannes KlingebielBut hype is not always the same; there are different forms and levels. I‘ve been trying my hand on a categorization based on my experience and my understanding of the phenomenon. This categorization is intended to help people better understand which form of hype they‘re confronted with.

[…]

Think of this scale as form of Richter scale to get a feel of how bad the hype is. A new technology doesn’t have to move through every single level but it most likely will at least reach level 3.

Individualism and collectivism in decentralised networks

I don’t agree with Paul Frazee’s point in this post about Twitter vs “p2p Twitters” (by which he means the Fediverse) but otherwise he makes good points about governance and what he calls “operational collectivism”.

There are two kinds of resources in a network:Source: Back to basics: What is the point of decentralization? | Paul FrazeeI start the conversation here because it sets the context for all decentralization: that we have mastered individualist operation and collectivist standardization but have failed at collectivist operation. The inability to collectively operate networks has created the conditions for large monopolies on the Internet.

- Individualist. The resource is owned by one stakeholder and doesn’t require cross-party coordination. Examples might include: tweets, blogposts, personal websites, likes and comments.

- Collectivist. The resource is owned by multiple stakeholders¹ and needs coordination between them. Examples might include: naming registries, package managers, cryptocurrency account balances, aggregated comment threads.

[…]

Whoever operates a collective resource has the power to change its implementation. The reason we decentralize operation is to distribute that power of implementation. If the stakeholders have the power of implementation, they’re able to ensure the resource represents their interests.

[…]

What’s the point of decentralization? It’s to ensure that the stakeholders — the end users — are represented. Individualism enforces personal control, while decentralized collectivism produces an intransigent consensus. We limit collectivist systems because they’re powerful systems, and power must always be checked.

Web3 and Ed3 are both problematic

Web3 is being discussed as if it’s anything other than the financialisation of everything. This post about ‘Ed3’ really struggles to square that circle when it comes to education. There are so many issues with it that I don’t really know where to start.

The bit that really jumped out for me, though, given that I’ve spent a decade working on Open Badges is the bit on credentialing. The cat is out of the bag by this point, especially in the “only paying for what you need” language. The whole point of education is that you don’t know what kind of person you’ll be at the end of it.

Anything else is just training.

Imagine if universities were fractionalized and you could earn the micro-credentials that mattered most for your career, only paid for what you needed, and owned a life-long portfolio with those credentials that were interoperable across all institutes & industries?Source: From Web3 to Ed3 - Reimagining Education in a Decentralized Worl… — MirrorWeb3 will also enable the metaverse to take shape over the next few decades; a universe of many buildable worlds that operate on decentralized infrastructure. The metaverse will make it possible to do everything we can do in the real world but enhanced by digital experiences & possible in an entirely virtual world.

Is QWERTY a really bad keyboard layout?

I’ve been able to touch-type since I was about 12 years of age, thanks to Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing. Like most people, I use the QWERTY layout, but I’ve always been curious about other layouts.

Apparently, it’s a bit of a myth that QWERTY was designed to slow typists down in case the mechanical keys got stuck. In the last edition of the Ultimate Typing Championship, all but one of the 26 competitors used QWERTY (and the one using the Dvorak layout came 12th).

The main thing to consider, in my opinion, is comfort. I remember being shocked once when I bought a keyboard and it came with a large warning that the use of any keyboard and mouse can cause ‘serious’ injuries.

This article talks about RSI (Repetitive Strain Injury), CTS (Carpal Tunnel Syndrome) and CTP (Carpal Tunnel Pressure).

If keyboard use does carry the risk of developing RSI, what is it about the keyboard that’s bad? Is it the physical design, the key layout, hand/wrist posture, or something else? My impression is that key layout is a relatively small component here, for several reasons. The first is my own experience, according to which it’s much more important to use a split keyboard, say, than the appropriate layout if I want to avoid RSI flare-ups. The second is that CTS is largely caused by CTP, which in theory seems more impacted by physical design (chiefly whether a keyboard is split and/or tilted/tented) and less by finger stretching or the horizontal rotating we do with our hands to reach keys at the sides of the keyboard. The third is Carpalx’s model, which suggests that established alternatives like Dvorak and Colemak, while better on the whole, use the pinky more heavily than does QWERTY – maybe it is a little bit bad to reach for the outermost keys, but any layout will have some keys at the extremes, so perhaps the difference between layouts just isn’t that great.Source: How Bad Is QWERTY, Really? A Review of the Literature, such as It Is | Erich GrunewaldWhat about QWERTY specifically? I wasn’t really able to find any research on this. Maybe that’s because it’s very hard to design experiments to test it? You can’t just take a bunch of people and ask half of them to start using Dvorak, because there’s a significant learning curve involved. But you don’t want to find out if learning a new layout is good, you want to find out using it is good once you have learned it. There is no natural control group for these experiments, and no obvious placebo.

In sum, keyboard use in general does seem to cause RSI, but the risk seems fairly small. Bad key layouts may only be a minor part of the RSI risk, though QWERTY does seem worse than most alternatives, relatively speaking. The evidence here is weak and my confidence intervals are wide.

A low-tech solution for personal warmth

My family, especially the female members, have always been big fans of the hot water bottle. So much so, in fact, that one of my wife’s favourite presents was receiving a long snake-shaped hot water bottle that she can use in various configurations.

As we face a bit of an energy crisis, hot water bottles are definitely something more people should be using, as this article explains.

A hot water bottle is a sealable container filled with hot water, often enclosed in a textile cover, which is directly placed against a part of the body for thermal comfort. The hot water bottle is still a common household item in some places – such as the UK and Japan – but it is largely forgotten or disregarded in most of the industrialised world. If people know of it, they usually associate it with pain relief rather than thermal comfort, or they consider its use an outdated practice for the poor and the elderly.Source: The Revenge of the Hot Water Bottle | LOW←TECH MAGAZINEAs early as the 1500s, people started to use all kinds of portable containers filled with hot coals from the fire. These were used as foot warmers, hand warmers, and bed warmers. Most were made of metal, either brass or copper, and placed inside wooden or ceramic enclosures to prevent skin burns. Over time, hot coals were replaced by hot water, which is a cleaner and safer heat storage medium.

Initially, these first “real” hot water bottles were made from hard materials such as glass, metal, or stoneware. It was only with the invention of vulcanised rubber in the nineteenth century that more comfortable lightweight and flexible hot water bottles became an option. Spanish friends told me that hot water bottles used to be made from animal skins, but I could not verify this. It may well be true, because all over the world there’s a long tradition of using “water skins” for storing liquids.

Kids need life on the highest volume

This article is based on the author’s experiences as a teacher in state schools in the US. I should imagine the situation is exacerbated there, but it can’t be that great elsewhere, either.

My own kids seem like they’re OK. Our youngest, whose had Covid like me this week, has gone back to remote learning, which she enjoys as she completes her work quickly and then does other things. I think it’s particularly hard on teenagers, like our eldest, who are preparing for important exams.

The data about learning loss and the mental health crisis is devastating. Overlooked has been the deep shame young people feel: Our students were taught to think of their schools as hubs for infection and themselves as vectors of disease. This has fundamentally altered their understanding of themselves.Source: I’m a Public School Teacher. The Kids Aren’t Alright. | Common SenseWhen we finally got back into the classroom in September 2020, I was optimistic, even as we would go remote for weeks, sometimes months, whenever case numbers would rise. But things never returned to normal.

When we were physically in school, it felt like there was no longer life in the building. Maybe it was the masks that made it so no one wanted to engage in lessons, or even talk about how they spent their weekend. But it felt cold and soulless. My students weren’t allowed to gather in the halls or chat between classes. They still aren’t. Sporting events, clubs and graduation were all cancelled. These may sound like small things, but these losses were a huge deal to the students. These are rites of passages that can’t be made up.

[…]

They are anxious and depressed. Previously outgoing students are now terrified at the prospect of being singled out to stand in front of the class and speak. And many of my students seem to have found comfort behind their masks. They feel exposed when their peers can see their whole face.

[…]

At the beginning of the pandemic, adults shamed kids for wanting to play at the park or hang out with their friends. We kept hearing, “They’ll be fine. They’re resilient.” It’s true that humans, by nature, are very resilient. But they also break. And my students are breaking. Some have already broken.

When we look at the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of history, I believe it will be clear that we betrayed our children. The risks of this pandemic were never to them, but they were forced to carry the burden of it. It’s enough. It’s time for a return to normal life and put an end to the bureaucratic policies that aren’t making society safer, but are sacrificing our children’s mental, emotional, and physical health.

Our children need life on the highest volume. And they need it now.

Paying for everything twice

As someone who’s recently started using a budgeting app, and who has a lot of music-making equipment lying around unused, I concur.

One financial lesson they should teach in school is that most of the things we buy have to be paid for twice.Source: Everything Must Be Paid for Twice | RaptitudeThere’s the first price, usually paid in dollars, just to gain possession of the desired thing, whatever it is: a book, a budgeting app, a unicycle, a bundle of kale.

But then, in order to make use of the thing, you must also pay a second price. This is the effort and initiative required to gain its benefits, and it can be much higher than the first price.

A new novel, for example, might require twenty dollars for its first price—and ten hours of dedicated reading time for its second. Only once the second price is being paid do you see any return on the first one. Paying only the first price is about the same as throwing money in the garbage.

Likewise, after buying the budgeting app, you have to set it all up, and learn to use it habitually before it actually improves your financial life. With the unicycle, you have to endure the presumably painful beginner phase before you can cruise down the street. The kale must be de-veined, chopped, steamed, and chewed before it gives you any nourishment.

If you look around your home, you might notice many possessions for which you’ve paid the first price but not the second. Unused memberships, unread books, unplayed games, unknitted yarns.

Ancient cynicism

As with stoicism, we’ve lost the ancient meaning of the word ‘cynicism’. I think you can probably tell a lot about how much love I have for Diogenes given that I named my phone after him (I name all my devices so I can easily identify them on wifi networks, etc.)

The original cynicism was a philosophical movement likely founded by Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, and popularized by Diogenes of Sinope around the fifth century B.C. It was based on a refusal to accept the assumptions and habits that discourage people from questioning conventional dogmas, and thus hold us back from the search for deep wisdom and happiness. Whereas a modern cynic might say, for instance, that the president is an idiot and thus his policies aren’t worth considering, the ancient cynic would examine each policy impartially.Source: We’ve Lost the True Meaning of Cynicism | The AtlanticThe modern cynic rejects things out of hand (“This is stupid”), while the ancient cynic simply withholds judgment (“This may be right or wrong”).

[…]

To pivot from the modern to the ancient, I recommend focusing each day on several original cynical concepts, none of which condemns the world but all of which lead us to question, and in many cases reject, worldly conventions and practices.

- Eudaimonia ("satisfaction")

- Askesis ("discipline")

- Autarkeia ("self-sufficiency")

- Kosmopolites ("cosmopolitanism")

E2EE is for everyone

Not only has the current UK government underfunded the NHS since coming to power in an attempt to introduce market-based medicine, orchestrated the unprecedented national self-sabotage that is Brexit, and attacked the BBC, but they’re also trying to convince the British public that end-to-end encryption (E2EE) is only wanted by paedophiles.

The hypocrisy of it knows no bounds. These are the same politicians who rely on the E2EE of WhatsApp, Signal, and other messaging services to plot against one another and society in general.

Critics sometimes claim that encryption makes it impossible to subpoena or obtain a warrant for information from people’s phones — this is bizarre because governments already demand such data. What they are actually complaining about is that the “platform” — for instance Facebook — no longer wants to be able to see the content themselves. The warrant will have to be served upon the device owner, not upon the (social) network provider.Source: Why we need #EndToEndEncryption and why it’s essential for our safety, our children’s safety, and for everyone’s future #noplacetohide | dropsafeGood security demands that data that we share amongst family and friends should remain available only to those family and friends; and likewise that data which we share with businesses should remain only with those businesses, and should only be used for agreed business purposes.

Network providers — and, importantly, messaging-network and social-network providers — are helping their users obtain better data security by cutting themselves off from the ability to access plaintext content. Simply: they don’t need to see it, and it’s not their job to police or censor it. Their adoption of end-to-end encryption makes everyone’s data safer.

The world needs end-to-end encryption. It needs more of it. We need the privacy, agency, and control over data that end-to-end encryption enables. And encryption is needed everywhere and by everyone — not just by politicians and police forces.

The life-changing difference of an internet connection

As someone who’s seemingly around the same age as the author of this post, I agree that the internet has made my life better. I didn’t have it anywhere near as hard as them while growing up, but my online connections (and research) have certainly helped me escape into a different life.

This is part of the story of how the internet changed my life for the better. I’m an early millennial and I was raised online. Through the internet, I found friends, support, and the human connection that I was lacking in real life. I also found valuable information that helped me help myself and sometimes help others. The key with information is always to effectively filter the good from the bad, which is a genuine life skill unto itself. My life today isn’t perfect, but it’s better than it’s ever been. My message to all the people out there who are struggling is to believe in yourself. If you help yourself and you let others help you, things are never hopeless.Source: The Internet Changed My Life | Pointers Gone Wild