Distro-hopping like a cynic

My own Linux journey has gone from Red Hat Linux, to Ubuntu, to Pop!_OS. However, today I’ve been messing about with Fedora Silverblue. I’m actually typing this on ChromeOS, which of course is also Linux.

What I like about The Register is their snarky, sarcastic style, which they put to good use in this article.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that all operating systems suck. Some just suck less than others.Source: The cynic’s guide to desktop Linux | The RegisterIt is also a comment under pretty much every Reg article on Linux that there are too many to choose from and that it’s impossible to know which one to try. So we thought we’d simplify things for you by listing how and in which ways the different options suck.

#AbolishTheMonarchy

It’s Jubilee weekend in the UK, not that I’m celebrating. Someone re-shared this classic article in The Irish Times from last year which expresses just the entire ridiculousness of venerating a talentless inbred family.

Source: Harry and Meghan: The union of two great houses, the Windsors and the Celebrities, is complete | The Irish TimesThe contemporary royals have no real power. They serve entirely to enshrine classism in the British nonconstitution. They live in high luxury and low autonomy, cosplaying as their ancestors, and are the subject of constant psychosocial projection from people mourning the loss of empire. They’re basically a Rorschach test that the tabloids hold up in order to gauge what level of hysterical batshittery their readers are capable of at any moment in time.

Epic UK walking trails

After walking Hadrian’s Wall (84 miles, 72 hours) a couple of months ago, I’m now seriously considering walking The Pennine Way (268 miles) next year. I reckon it might take a couple of weeks, as I absolutely beasted myself to do Hadrian’s Wall so quickly.

If you can’t spare a week to walk Britain’s mountain trails, coastal tracks and riverside paths, head for these expert-picked highlightsSource: The best of the UK’s most epic walking trails in 2-3 days | The Guardian

Epic UK walking trails

After walking Hadrian’s Wall (84 miles, 72 hours) a couple of months ago, I’m now seriously considering walking The Pennine Way (268 miles) next year. I reckon it might take a couple of weeks, as I absolutely beasted myself to do Hadrian’s Wall so quickly.

If you can’t spare a week to walk Britain’s mountain trails, coastal tracks and riverside paths, head for these expert-picked highlightsSource: The best of the UK’s most epic walking trails in 2-3 days | The Guardian

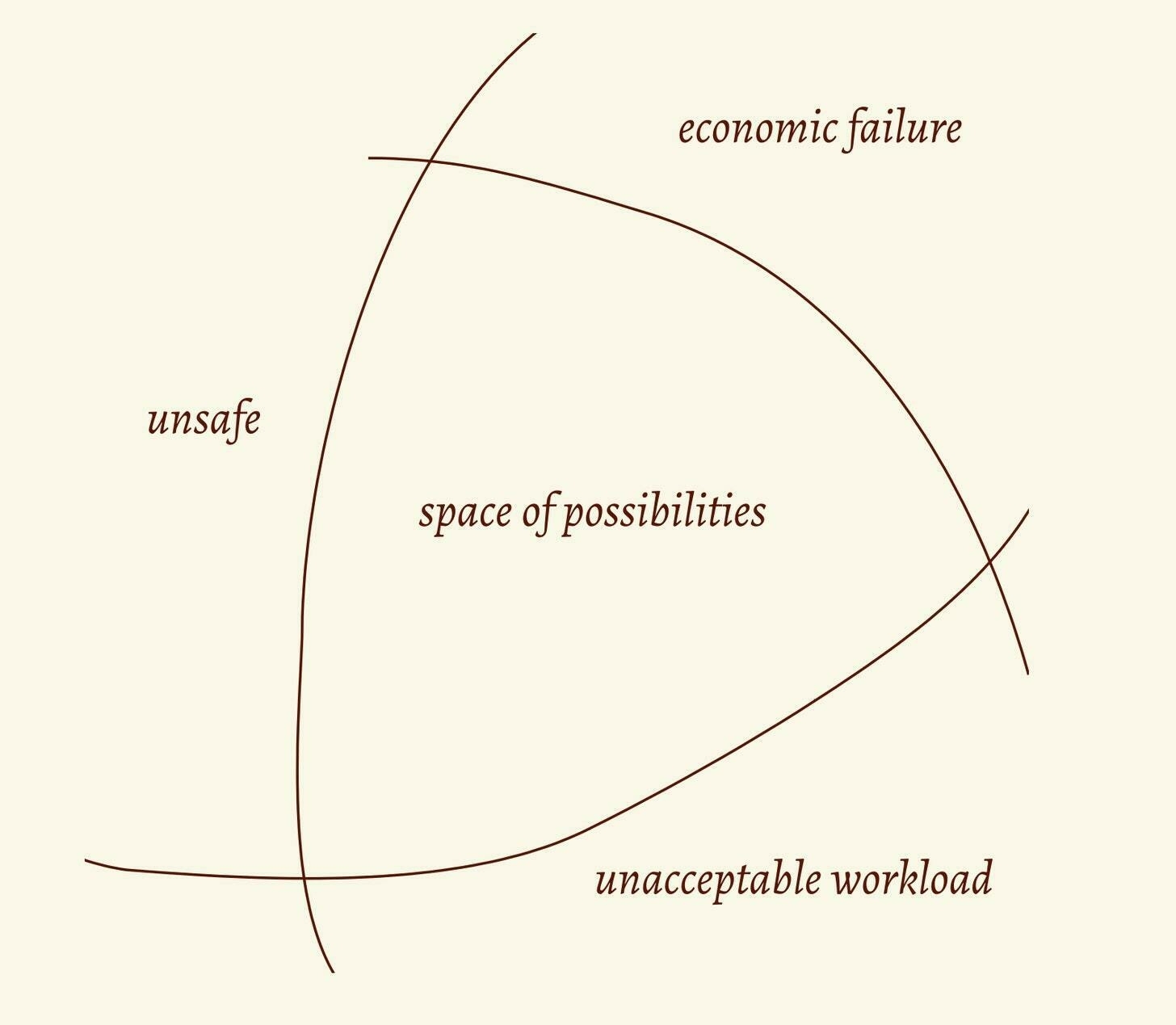

Space of possibilities

In Andrew Curry’s latest missive, his ‘two things’ are Climate and Business. The diagram below is actually from the latter section, but I think it’s actually also very relevant for the former.

At his Roblog blog, Rob Miller has a short and engaging post on why businesses fail over time. I’m not sure it’s right, but it’s certainly interesting, and he tells the story through three diagrams.Source: 4 May 2022. Climate | Business - Just Two ThingsHe argues—following the work of Jens Rasmussen—that successful businesses operate in a safe space that sits between economic failure, on one side, lack of safety, on another, and overload, on a third.

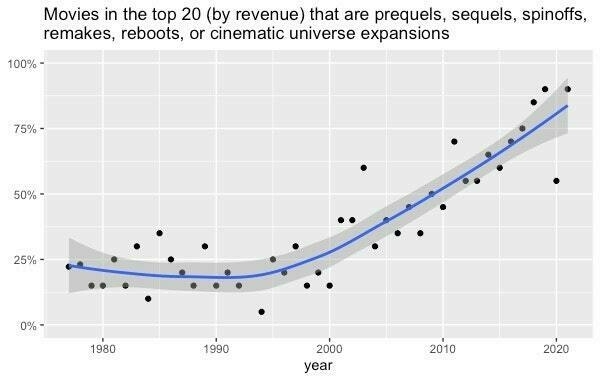

Popular culture has become an endless parade of sequels

Once you start recognising colour schemes and sound effects, every new film ends up looking and sounding the same.

Yes, I’m getting old, but as Adam Mastroianni from Experimental History explains, there’s shifts happening in everything from books to video games.

The problem isn’t that the mean has decreased. It’s that the variance has shrunk. Movies, TV, music, books, and video games should expand our consciousness, jumpstart our imaginations, and introduce us to new worlds and stories and feelings. They should alienate us sometimes, or make us mad, or make us think. But they can’t do any of that if they only feed us sequels and spinoffs. It’s like eating macaroni and cheese every single night forever: it may be comfortable, but eventually you’re going to get scurvy.Source: Pop Culture Has Become an Oligopoly | Experimental History[…]

Fortunately, there’s a cure for our cultural anemia. While the top of the charts has been oligopolized, the bottom remains a vibrant anarchy. There are weird books and funky movies and bangers from across the sea. Two of the most interesting video games of the past decade put you in the role of an immigration officer and an insurance claims adjuster. Every strange thing, wonderful and terrible, is available to you, but they’ll die out if you don’t nourish them with your attention. Finding them takes some foraging and digging, and then you’ll have to stomach some very odd, unfamiliar flavors. That’s good. Learning to like unfamiliar things is one of the noblest human pursuits; it builds our empathy for unfamiliar people. And it kindles that delicate, precious fire inside us––without it, we might as well be algorithms. Humankind does not live on bread alone, nor can our spirits long survive on a diet of reruns.

The Climate Game

The Financial Times has a free-to-play game where the aim is to try and keep global warming to only 1.5°C by the year 2100. There are different things to choose from and decisions to make.

I only managed to keep it to 1.88°C and still had to make some pretty drastic decisions. We’re utterly screwed. We need to act on the climate crisis, but also start adapting too.

(also worth looking at the article on how they made this)

See if you can save the planet from the worst effects of climate changeSource: The Climate Game — Can you reach net zero? | Financial Times

14 Common Features of Fascism

This is from six years ago but it’s worth revisiting as I don’t think it’s too much of a push to see these elements at play in the USA right now. Which, if you think about the role that country played up until recently, is staggering.

Fascism and authoritarianism change over time, however, and so it’s worth also listening to a recent episode of the BBC Radio 4 Thinking Allowed programme on ‘Strongmen’. For example, instead of banning elections, fascists/authoritarian allow the democratic veneer to remain, they just ensure that the result goes they way they want.

While Eco is firm in claiming “There was only one Nazism,” he says, “the fascist game can be played in many forms, and the name of the game does not change.” Eco reduces the qualities of what he calls “Ur-Fascism, or Eternal Fascism” down to 14 “typical” features. “These features,” writes the novelist and semiotician, “cannot be organized into a system; many of them contradict each other, and are also typical of other kinds of despotism or fanaticism. But it is enough that one of them be present to allow fascism to coagulate around it.”Source: Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism | Open Culture

- The cult of tradition. “One has only to look at the syllabus of every fascist movement to find the major traditionalist thinkers. The Nazi gnosis was nourished by traditionalist, syncretistic, occult elements.”

- The rejection of modernism. “The Enlightenment, the Age of Reason, is seen as the beginning of modern depravity. In this sense Ur-Fascism can be defined as irrationalism.”

- The cult of action for action’s sake. “Action being beautiful in itself, it must be taken before, or without, any previous reflection. Thinking is a form of emasculation.”

- Disagreement is treason. “The critical spirit makes distinctions, and to distinguish is a sign of modernism. In modern culture the scientific community praises disagreement as a way to improve knowledge.”

- Fear of difference. “The first appeal of a fascist or prematurely fascist movement is an appeal against the intruders. Thus Ur-Fascism is racist by definition.”

- Appeal to social frustration. “One of the most typical features of the historical fascism was the appeal to a frustrated middle class, a class suffering from an economic crisis or feelings of political humiliation, and frightened by the pressure of lower social groups.”

- The obsession with a plot. “Thus at the root of the Ur-Fascist psychology there is the obsession with a plot, possibly an international one. The followers must feel besieged.”

- The enemy is both strong and weak. “By a continuous shifting of rhetorical focus, the enemies are at the same time too strong and too weak.”

- Pacifism is trafficking with the enemy. “For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life but, rather, life is lived for struggle.”

- Contempt for the weak. “Elitism is a typical aspect of any reactionary ideology.”

- Everybody is educated to become a hero. “In Ur-Fascist ideology, heroism is the norm. This cult of heroism is strictly linked with the cult of death.”

- Machismo and weaponry. “Machismo implies both disdain for women and intolerance and condemnation of nonstandard sexual habits, from chastity to homosexuality.”

- Selective populism. “There is in our future a TV or Internet populism, in which the emotional response of a selected group of citizens can be presented and accepted as the Voice of the People.”

- Ur-Fascism speaks Newspeak. “All the Nazi or Fascist schoolbooks made use of an impoverished vocabulary, and an elementary syntax, in order to limit the instruments for complex and critical reasoning.”

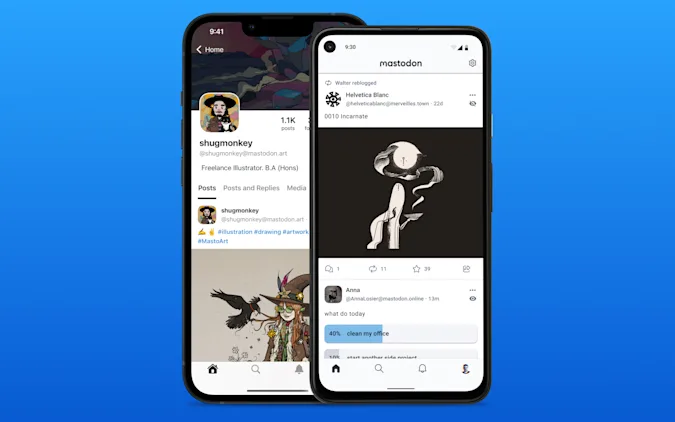

Are we really calling it #Elongate?

There’s been a noticeable influx of people to the Fediverse over the last few days due to Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter.

What I find really interesting are three things:

- Those arriving inevitably compare five year-old, federated, open-source software developed mainly by two people with a fifteen year-old publicly-traded company. The fact that they're even comparable is frankly amazing, if you think about the money poured into Twitter over the years.

- Some people already on the Fediverse seem to think they have to act differently and/or take time to explain all of the things to people arriving from Twitter. I'm not sure that's necessary. People learn by watching, imitating, and practising.

- There's plenty of people (including me, I guess, to some extent) who are keen to point out that they've been around on the Fediverse for quite a while, thank you very much.

“Funnily enough one of the reasons I started looking into the decentralized social media space in 2016, which ultimately led me to go on to create Mastodon, were rumours that Twitter, the platform I’d been a daily user of for years at that point, might get sold to another controversial billionaire,” he wrote. “Among, of course, other reasons such as all the terrible product decisions Twitter had been making at that time. And now, it has finally come to pass, and for the same reasons masses of people are coming to Mastodon.”Source: After Musk's Twitter takeover, an open-source alternative is 'exploding' | Engadget

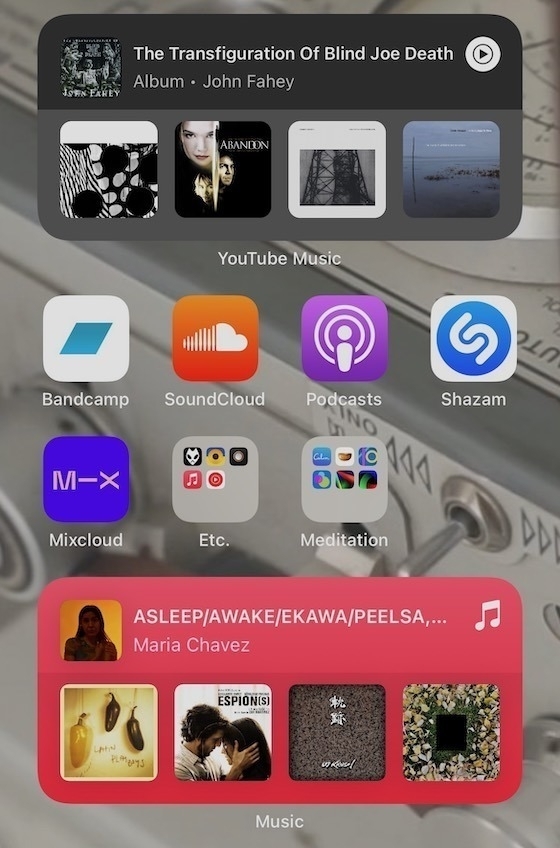

Dedicated portable digital media players and central listening devices

I listen to music. A lot. In fact, I’m listening while I write this (Busker Flow by Kofi Stone). This absolutely rinses my phone battery unless it’s plugged in, or if I’m playing via one of the smart speakers in every room of our house.

I’ve considered buying a dedicated digital media player, specifically one of the Sony Walkman series. But even the reasonably-priced ones are almost the cost of a smartphone and, well, I carry my phone everywhere.

It’s interesting, therefore, to see Warren Ellis' newsletter shoutout being responded to by Marc Weidenbaum. It seems they both have dedicated ‘music’ screens on their smartphones. Personally, I use an Android launcher that makes that impracticle. Also, I tend to switch between only four apps: Spotify (I’ve been a paid subscriber for 13 years now), Auxio (for MP3s), BBC Sounds (for radio/podcasts), and AntennaPod (for other podcasts). I don’t use ‘widgets’ other than the player in the notifications bar, if that counts.

Highlights from 'The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is'

On my flight back from Croatia at the weekend, I managed to read the entirety of The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, A Philosophy, A Warning by Justin E.H. Smith. To be honest, the book itself is not what you think it is, as Sam Kriss notes in his (equally good) review.

I have a background in Philosophy which might have helped with this book, as it delves into the history of ideas quite a bit. Although he outlines four 'charges' against the internet, the main thesis that I understand Smith as postulating is that the internet, and in particular the culture around it, shouldn't be seen as a revolutionary break with what has gone before.

To my mind, Smith makes some good arguments, although he gets too bogged-down with Leibniz for my liking. But in general, I like the book and gave it 4.5 stars out of five on Literal.club. What follows are some of my favourite sections of the book, which I'd encourage you to read.

As the quotations I'm using are fairly lengthy, I'll introduce each one. In this first one, Smith talks about his phenomenological approach which focuses on actual usage of terms.

It seems reasonable terminologically to follow actual usage, and it seems conceptually justified to focus on the small corner of the internet that is phenomenologically most salient to human life, just as when we speak of “life on earth” we often have humans and animals foremost in mind, even though all the plant life on earth weighs over two hundred times more than all the animals combined, in terms of total biomass. Animals are a tiny sliver of life on earth, yet they are preeminently what we mean when we talk about life on earth; social media are a tiny sliver of the internet, yet they are what we mean when we speak of the internet, as they are where the life is on the internet. (Thus, “internet” serves as a sort of reverse synecdoche, the larger containing term standing for the smaller contained term. The reason for adopting this terminology is that it seems to agree with actual usage among current English speakers; on Twitter, for example, you will often see users declaring exasperatedly that their antagonists need to “get off the internet” and “touch grass.” Here, they don’t really mean the whole internet; they mean Twitter. (p.17)

The four charges that Smith makes are that the internet is addictive, that it shapes human life algorithmically, that there is no democratic oversight of social media, and that it works as a universal surveillance device.

The principal charges against the internet, deserving of our attention here, instead have to do with the ways in which it has limited our potential and our capacity for thriving, the ways in which it has distorted our nature and fettered us. Let us enumerate them. First, the internet is addictive and is thus incompatible with our freedom, conceived as the power to cultivate meaningful lives and future-oriented projects in which our long-term, higher-order desires guide our actions, rather than our short-term, first-order desires. Second, the internet runs on algorithms, and shapes human lives algorithmically, and human lives under the pressure of algorithms are not enhanced, but rather warped and impoverished. To the extent that we are made to conform to them, we experience a curtailment of our freedom. Third, there is little or no democratic oversight regarding how social media work, even though their function in society has developed into something far more like a public utility, such as running water, than like a typical private service, such as dry cleaning. Private companies have thus moved in to take care of basic functions necessary for civil society, but without assuming any real responsibility to society. This, too, is a diminution of the political freedom of citizens of democracy, understood as the power to contribute to decisions concerning our social life and collective well-being. What Michael Walzer said of socialism might be said of democracy too: that “what touches all should be decided by all.” And on this reckoning, the internet is aggressively undemocratic. Fourth, the internet is now a universal surveillance device, and for this reason as well it is incompatible with the preservation of our political freedom. (p.18-19)

Smith goes on to explain the impact of each of these and starts to talk about how the problems interact with one another.

This then is the first thing that is truly new about the present era: a new sort of exploitation, in which human beings are not only exploited in the use of their labor for extraction of natural resources; rather, their lives are themselves the resource, and they are exploited in its extraction.

[...]

This then is the second new problem of the internet era: the way in which the emerging extractive economy threatens our ability to use our mental faculty of attention in a way that is conducive to human thriving. Both the first and second problems are aggravated significantly with the rise of the mobile internet, and what Citton astutely labels “affective condensation.” Most of our passions and frustrations, personal bonds and enmities, responsibilities and addictions, are now concentrated into our digital screens, along with our mundane work and daily errands, our bill-paying and our income tax spreadsheets. It is not just that we have a device that is capable of doing several things, but that this device has largely swallowed up many of the things we used to do and transformed these things into various instances of that device’s universal imposition of itself: utility has crossed over into compulsoriness.

[...]

This then is the third feature of our current reality that constitutes a genuine break with the past: the condensation of so much of our lives into a single device, the passage of nearly all that we do through a single technological portal. This consolidation, of course, helps and intensifies the first two novelties of our era that we identified, namely, the extraction of attention from human subjects as a sort of natural resource, and the critical challenge this new extractive economy poses to our mental faculty of attention.

[...]

If we all find it difficult to distinguish between advertisement and not-advertisement, this is in part because, today, all is advertisement. Or, to put this somewhat more cautiously, there is no part of our most important technology products and services that is kept cordoned off as a safe space from the commercial interests of the companies that own them.

[...]

This then is the fourth genuine novelty of the present era: in the rise of an economy focused on extracting information from human beings, these human beings are increasingly perceived and understood as sets of data points; and eventually it is inevitable that this perception cycles back and becomes the self-perception of human subjects, so that those individuals will thrive most, or believe themselves to thrive most, in this new system who are able convincingly to present themselves not as subjects at all, but as attention-grabbing sets of data points. (p.24-28)

Smith uses the example of a partnership between Ancestry and Spotify to be able to 'play the music that fits with your heritage'. It was a cynical marketing ploy, but he uses it to illustrate a wider point about the role of algorithms in society. His point is a nuanced and important one about how we serve algorithms, rather than having them serve us.

We are not, yet, accustomed to seeing these different trends—the corporate opportunism of Ancestry and Spotify; the sinister right-wing populism of the aforementioned leaders; and the identitarian campaigns for cultural purity driven mostly by young self-styled “progressives” on social media—as inflections of the same broad historical phenomenon. But perhaps their commonality may become clearer when we consider all of them as symptoms of an underlying and much vaster historical shift: the shift to ubiquitous algorithmic management of society, which lends advantage to the expression of opinions unambigous enough (i.e., dogmatic or extremist enough) for AI to detect their meaning and to process them accordingly, and which also removes from the individual subject any deep existential imperative or moral duty to cultivate self-understanding, instead allowing the sort of vectors of identity that even AI can pick up and process to substitute for any real idea of who an individual is or might yet hope to be. (p.56)

In 2011 there was a lot written about how the internet, and social media in particular, was bringing about a new positive world order. There was talk of a 'deliberative democracy', but actually (Smith points out) that never materialised.

What we have in fact obtained in place of this is a farcical imitation of deliberation, in which algorithms are designed by the companies that provide the platforms for discussion in order to maximize engagement, a purpose that is self-evidently at odds with the goal of conflict resolution or consensus-building. Social media are in this respect engines of perpetual disagreement, which sharpen opposing views into stark dichotomies and preclude the possibility of either exploring partial common ground or finding agreement in a dialectical fashion in some higher-order synthesis of what at the first order appear as contradictory positions. (p.59-60)

Chapter 2 is the pivotal chapter, as Smith outlines what I consider to be his main thesis that historical human interactions pre-empted internet culture.

The internet is still not what you think it is.

For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as the previous chapter made it appear. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols. (p.64)

He continues some pages later on the same theme.

Anthropogenic alterations of the natural environment are often too subtle to detect, even when they profoundly transform it, as for example in efforts to distinguish controlled-burning events from naturally occurring fires in human prehistory, or perhaps in the particular quality of Amazonian biodiversity today. If we were not so attached to the idea that human creations are of an ontologically different character than everything else in nature—that, in other words, human creations are not really in nature at all, but extracted out of nature and then set apart from it—we might be in a better position to see human artifice, including both the mass-scale architecture of our cities and the fine and intricate assembly of our technologies, as a properly natural outgrowth of our species-specific activity. It is not that there are cities and smartphones wherever there are human beings, but cities and smartphones themselves are only the concretions of a certain kind of natural activity in which human beings have been engaging all along. (p.89)

As a philosopher, Smith draws on a rich history of ideas and can weave together quite the rich picture of how the internet fits in with that history.

I am not, here, going quite so far as to say that the internet proves the truth of the theory of the world soul as it descends from Greek antiquity to the present day. I am too responsible to say that. Rather, I will carefully venture, as I began to do in the previous chapters, to note that it will help us to understand the nature and significance of the internet to consider it as only the most recent chapter in a much longer, and much deeper, history. (p.130)

From here, there's a fascinating discussion of metaphor and what counts as 'simulation'. There's also a great section on AI. So I'd encourage you to read it!

The economics of blockchain-based gaming don't add up

Blake Robbins, who used to work on game design at Roblox, has written an in-depth post on why blockchain-based gaming will never take off.

TL;DR: not only is it likely to be a Ponzi scheme, it's just a really bad idea for basic economic reasons.

Narratives can be moulded, but unfortunately crypto gaming evangelists will not be able to change basic economics. The fact that the problem with the Mundell-Fleming trilemma and how crypto games fall on the wrong side of them from a pure game design perspective which ultimately prevent large developers from creating AAA games with open economies as well as ruining user experience is totally ignored by VCs who are funnelling absurd amounts of money into these projects makes me question if they actually believe in the narrative they’re pushing, or if they’re simply investing in token pre-sales and planning on dumping on unwitting retail bagholders.

For the record, I’m not a crypto hater or anything... [h]owever, I just don’t see the application of decentralised blockchains in gaming, there isn’t a need. Putting games on the blockchain will just result in really slow servers as everything would constantly have to be verified by a decentralised database. No one gamer has ever said: “I don’t trust Rockstar to store my data correctly which is why I won’t buy GTA V”. Building games for the sole purpose of “play to earn” or “play to own” means that players are no longer playing games for enjoyment, but rather the hope that they can monetise their holdings. Inevitably, this means that the quality of game experience will drop, as developers focus solely on how to turn every single aspect of a game into an NFT which can be traded. Collectible trading should be complementary, like in Roblox or Counter-Strike , it should not be the whole purpose of a game. You might as well scrap the game altogether, and just focus on making NFT collections like Bored Apes or Cryptopunks. Recreating games to have a similiar culture will not work out.

Literally shitposting

I saw this mentioned in passing and thought it was unusual enough to share here. There's a metaphor in there somewhere...

In July 1184 Henry VI, King of Germany (later Holy Roman Emperor), held court at a Hoftag in Erfurt. On the morning of 26 July, the combined weight of the assembled nobles caused the wooden second story floor of the assembly building to collapse and most of them fell through into the latrine cesspit below the ground floor, where about 60 of them drowned in liquid excrement. This event is called Erfurter Latrinensturz (lit. 'Erfurt latrine fall') in several German sources.

Assume that your devices are compromised

I was in Catalonia in 2017 during the independence referendum. The way that people were treated when trying to exercise democratic power I still believe to be shameful.

These days, I run the most secure version of an open operating system on my mobile device that I can. And yet I still need to assume it's been compromised.

In Catalonia, more than sixty phones—owned by Catalan politicians, lawyers, and activists in Spain and across Europe—have been targeted using Pegasus. This is the largest forensically documented cluster of such attacks and infections on record. Among the victims are three members of the European Parliament, including Solé. Catalan politicians believe that the likely perpetrators of the hacking campaign are Spanish officials, and the Citizen Lab’s analysis suggests that the Spanish government has used Pegasus. A former NSO employee confirmed that the company has an account in Spain. (Government agencies did not respond to requests for comment.) The results of the Citizen Lab’s investigation are being disclosed for the first time in this article. I spoke with more than forty of the targeted individuals, and the conversations revealed an atmosphere of paranoia and mistrust. Solé said, “That kind of surveillance in democratic countries and democratic states—I mean, it’s unbelievable.”

[...]

[T]here is evidence that Pegasus is being used in at least forty-five countries, and it and similar tools have been purchased by law-enforcement agencies in the United States and across Europe. Cristin Flynn Goodwin, a Microsoft executive who has led the company’s efforts to fight spyware, told me, “The big, dirty secret is that governments are buying this stuff—not just authoritarian governments but all types of governments.”

[...]

The Citizen Lab’s researchers concluded that, on July 7, 2020, Pegasus was used to infect a device connected to the network at 10 Downing Street, the office of Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. A government official confirmed to me that the network was compromised, without specifying the spyware used. “When we found the No. 10 case, my jaw dropped,” John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at the Citizen Lab, recalled. “We suspect this included the exfiltration of data,” Bill Marczak, another senior researcher there, added. The official told me that the National Cyber Security Centre, a branch of British intelligence, tested several phones at Downing Street, including Johnson’s. It was difficult to conduct a thorough search of phones—“It’s a bloody hard job,” the official said—and the agency was unable to locate the infected device. The nature of any data that may have been taken was never determined.

Source: How Democracies Spy On Their Citizens | The New Yorker

What technology means in late capitalism

Anyone familiar with Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle will appreciate this article by Jonathan Crary, author of the short but impressive 24/7 Capitalism.

Crary's argument is that our current status quo depends on a capital-fuelled extractive mikitary-industriiall complex that cannot be sustained. What comes next can't (isn't likely to look like) just a 'Green New Deal' version of it.

Any possible path to a survivable planet will be far more wrenching than most recognize or will openly admit. A crucial layer of the struggle for an equitable society in the years ahead is the creation of social and personal arrangements that abandon the dominance of the market and money over our lives together. This means rejecting our digital isolation, reclaiming time as lived time, rediscovering collective needs, and resisting mounting levels of barbarism, including the cruelty and hatred that emanate from online. Equally important is the task of humbly reconnecting with what remains of a world filled with other species and forms of life. There are innumerable ways in which this may occur and, although unheralded, groups and communities in all parts of the planet are moving ahead with some of these restorative endeavors.

However, many of those who understand the urgency of transitioning to some form of eco-socialism or no-growth post-capitalism carelessly presume that the internet and its current applications and services will somehow persist and function as usual in the future, alongside efforts for a habitable planet and for more egalitarian social arrangements. There is an anachronistic misconception that the internet could simply “change hands,” as if it were a mid-20th-century telecommunications utility, like Western Union or radio and TV stations, which would be put to different uses in a transformed political and economic situation.But the notion that the internet could function independently of the catastrophic operations of global capitalism is one of the stupefying delusions of this moment. They are structurally interwoven, and the dissolution of capitalism, when it happens, will be the end of a market-driven world shaped by the networked technologies of the present.

Of course, there will be means of communication in a post-capitalist world, as there always have been in every society, but they will bear little resemblance to the financialized and militarized networks in which we are entangled today. The many digital devices and services we use now are made possible through unending exacerbation of economic inequality and the accelerated disfiguring of the earth’s biosphere by resource extraction and needless energy consumption.

Using DICE instead of RA(S)CI

I like what the RACI responsibility assignment matrix tries to do in clarifying roles and responsibilities. In practice, I tend to favour RASCI which adds a 'support' role.

But I also agree with this article by Clay Parker Jones which suggests an alternative.

RACI is vague, hard to use, and reinforces the "what the hell is happening here" status quo. DICE is specific, easy to use, and shines a bright light on dysfunction.

The value of a liberal education

I have degrees in Philosophy, History, and Education. As such, I have received what most would call a ‘liberal education’.

These days, people don’t put as much store in a liberal education as they used to, which is a shame. In fact, many people don’t even know what it means. SMBC explains.

SMBC is a daily comic strip about life, philosophy, science, mathematics, and dirty jokes.Source: Liberal Education | Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal

'Live Forever' mode

My first response to this article was ‘why?’ My second was realising that this in no way is ‘living forever’. Utterly pointless.

The death of [Somnium Space CEO] Sychov’s father served as the inspiration for an idea that he would come to call “Live Forever” mode, a forthcoming feature in Somnium Space that allows people to have their movements and conversations stored as data, then duplicated as an avatar that moves, talks, and sounds just like you—and can continue to do so long after you have died. In Sychov’s dream, people will be able to talk to their dead loved one whenever they wish.Source: Metaverse Company to Offer Immortality Through ‘Live Forever’ Mode | Vice“Literally, if I die—and I have this data collected—people can come or my kids, they can come in, and they can have a conversation with my avatar, with my movements, with my voice,” he told me. “You will meet the person. And you would maybe for the first 10 minutes while talking to that person, you would not know that it’s actually AI. That’s the goal.”

[…]

But even with all the ethical preparation and experience the company can muster, there will be inevitable and justifiable ethical questions about allowing a version of a self to continue on in perpetuity. What if, for example, the children of a deceased Somnium Space user found it painful to know he was continuing on in some form in their metaverse?

The rise of first-party online tracking

In a startling example of the Matthew effect of accumulated advantage, the incumbent advertising giants are actually being strengthened by legislation aimed to curb their influence. Because, of course.

Source: How You’re Still Being Tracked on the Internet | The New York TimesFor years, digital businesses relied on what is known as “third party” tracking. Companies such as Facebook and Google deployed technology to trail people everywhere they went online. If someone scrolled through Instagram and then browsed an online shoe store, marketers could use that information to target footwear ads to that person and reap a sale.

[...]Now tracking has shifted to what is known as “first party” tracking. With this method, people are not being trailed from app to app or site to site. But companies are still gathering information on what people are doing on their specific site or app, with users’ consent. This kind of tracking, which companies have practiced for years, is growing.

[...]The rise of this tracking has implications for digital advertising, which has depended on user data to know where to aim promotions. It tilts the playing field toward large digital ecosystems such as Google, Snap, TikTok, Amazon and Pinterest, which have millions of their own users and have amassed information on them. Smaller brands have to turn to those platforms if they want to advertise to find new customers.

It's time to accept that centralised social media won't change

A great blog post by Chris Trottier about actually doing something about the problems with centralised social media, by refusing to be a part of it any more.

As an aside, once you see the problem with capitalism mediating every human relationship and interest, you can’t un-see it. For example, I’m extremely hostile to advertising. I really can’t stand it these days.

Centralized social media won't change. No regulatory bodies are coming to the rescue. If you hang around Twitter or Facebook long enough, no benevolent CEO will sprinkle magic pixie dust to make it better.Source: What should we do about toxic social media? | PeerverseAcceptance is no small thing. If you’ve spent years on a social network, investing in relationships, it’s hard to accept that all that effort was a waste. I’m not talking about the people you build friendships with, but the companies and services that connect you. Twitter and Facebook are the nuclear ooze of the Internet, and nothing’s going to make them better.

It’s time to let go. Toxic social media doesn’t care about you, it just wants to exploit you. To them, you’re inventory, a blip in a database.

[…]

Getting rid of toxic social media is about building a future without it. There’s thousands of developers working on an open web, all who are dedicated to building a better Internet. Still, if we want those walled gardens to be dismantled, we must let developers know it’s worth while to code an alternative.

Thus, it's time to accept centralized social media for what it is: it is toxic and won't change. Once you accept this, vote with your feet. Then vote with your wallet.