Collectively-owned Fediverse instances

I’m essentially bookmarking this publicly as it’s a useful reference for Fediverse instances (all currently running Mastodon!) which are collectively owned.

What I’m interested in is diversifying and going beyond this very useful list. First, I’d love examples to be added which are running other Fediverse software than Mastodon. For example, I’ve got a test instance of Misskey running at wao.wtf.

Second, I’m interested in the governance of these instances. If you’re not involved with co-operatives or other organisations that are democratically operated, it can seem like a bit of a black box. So I think we need a collaboratively-created guide to collective decision-making processes when it comes to Fediverse instances.

Fediverse instances with an explicit system of shared governance, usually made legally binding through an incorporated association or cooperative.Source: Collectively owned instances - fediparty | Codeberg.orgThis page will list also instances which are closed for registrations and dead instances, so that we can collectively learn from their experience.

Originally created by @nemobis@mamot.fr inspired by a @Matt_Noyes@social.coop thread.

Prestige and associational value

This is 100% true and one of the reasons that I think that Open Badges and Verifiable Credentials are so awesome. Associational value is built-in for human beings, as we’re social creatures who set store by what other people value.

For example, I’m Dr. Belshaw which has a certain cachet and status in some circles. But people are usually much more interested/impressed by the fact that I worked for Mozilla and that one of our co-op’s clients is Greenpeace.

Them’s the breaks. And I feel like passing on this kind of wisdom to the younger generations is really important, to be honest, as a way that the world actually works.

A lot of people suspect that having-been part of a prestigious organisation (such a a famous university or an "elite" org in your field) gets you an unfair advantage when applying for future jobs.Source: Associational Value | Atoms vs BitsThere are two main avenues you could imagine for this advantage. One is basically nepotism: through the organisation you meet lots of other people who will later give you preferential access to jobs.

A second avenue is throughthe associtional value of the institution: that people with no specific connection to you or that organisation will see the name of Prestigious Institution on your resume and hire you because, well, you were at Prestigious Institution.

[…]

I think associational value often comes out of single-sentence descriptions of what somebody has done, and that therefore there are often relatively-easy ways to get 99% of the associational benefits of a prestigious institution at a much lower cost.

For example, in the magazine-writing world, people are often (approximately) defined by 1-3 of the most famous publications they’ve ever written for: “X’s work has appeared in TK, TK and TK,” or “this is my friend Y, she writes for [famous media brand].”

[…]

I’m not entirely sure how to work around this one, beyond the “try to get a mild affiliation with a prestigious institution, even if it’s an incredibly silly one” hack.

Richard Hammond's near-death experience

Richard Hammond, co-presenter of the original Top Gear and The Grand Tour reflects on his near-death experience. Worth a watch.

[embed]www.youtube.com/watch

Source: Richard Hammond explains what he experienced during his coma | 310mph Crash | YouTube

Some tips for adding winter cheer

There are some excellent suggestions in this list of 53 things that can give you a lift over the winter months. I’ve highlighted three of my favourites below!

7. Walk with an audio book On a crisp winter’s day, there is no finer companion than 82-year-old actor Seán Barrett. His sublime narration of Mick Herron’s Slough House series, about a bunch of MI5 outcasts, will bring cheer to the gloomiest days.Source: Need a lift? Here’s 53 easy ways to add cheer to your life as winter looms | The Guardian[…]

18. Buy foods you can’t identify Purchase food in shops where the majority of products have no English on the packaging, so eating what you buy is an adventure. It might be black limes, a box of tamarinds or a rosewater drink with vermicelli pieces. It’s like travelling without travelling.

[…]

50. Sweat in a sauna We’ve all been told about the wellbeing boost of plunging into cold water, wild swimming and turning your shower down to freezing. But who wants to be cold? Book yourself into a sauna. Let the heat and steam soak deep into your bones and sweat out all your worries.

Convivial social networking

Adam Greenfield composed a thread this morning on Mastodon in which he referenced Ivan Illich’s call for conviviality. This was also referenced in a post by Audrey Watters which was shared a few minutes later in my timeline by Aaron Davis.

Such synchronicity is, of course, entirely random but meshed well with my state of mind this morning. I find it interesting that Audrey thinks it’s ridiculous to think that Mastodon is “what’s next” and instead looks to email. For what it’s worth, I see the Fediverse as being a lot like email, actually.

Given that she’s got a brain and experience several times the size of mine, I’d love it if she wrote more about this…

It's easy to look at the world right now and focus on the shit... The Republican takeover of the House. The economy. The way my body feels after running 6.85 miles on Sunday morning and then sitting in the car for 2+ hours on the drive home. The implosion of Twitter. The ridiculousness of suggesting Mastodon is "what's next." And so on. I mean, I have lots of thoughts on all of these, particularly the Twitter and Mastodon brouhaha. I read an email newsletter that referenced a Twitter thread in which Alexis Madrigal argued that Twitter, at least in its original manifestation, was for "word people." I quite like that framework, and it's helpful in showcasing how Facebook and now TikTok really would rather the ascendant influencers be picture people. TV people, even. It's time to pull out 'Tools for Conviviality', perhaps, for a re-read, because I'm loathe to make the argument that email is, in fact, where we find technological conviviality these days. But that's the direction I'm considering taking the argument. If I were to write about it and think about it more, that is.Source: The Week in Review: What's Good | Audrey Watters

Mourning what we've lost

I found this an eloquent explanation of emotions and feelings I've experienced over the last couple of weeks as the Fediverse has been 'invaded' by people considering themselves 'refugees' from Twitter.

As Hugh Rundle points out in this post, some of us have already mourned what we'd lost with Twitter and had made our home in a comfy, homely new place. There were rules, both implicit and explicit, about how to behave, but now...

For those of us who have been using Mastodon for a while (I started my own Mastodon server 4 years ago), this week has been overwhelming. I've been thinking of metaphors to try to understand why I've found it so upsetting. This is supposed to be what we wanted, right? Yet it feels like something else. Like when you're sitting in a quiet carriage softly chatting with a couple of friends and then an entire platform of football fans get on at Jolimont Station after their team lost. They don't usually catch trains and don't know the protocol. They assume everyone on the train was at the game or at least follows football. They crowd the doors and complain about the seat configuration.

It's not entirely the Twitter people's fault. They've been taught to behave in certain ways. To chase likes and retweets/boosts. To promote themselves. To perform. All of that sort of thing is anathema to most of the people who were on Mastodon a week ago. It was part of the reason many moved to Mastodon in the first place. This means there's been a jarring culture clash all week as a huge murmuration of tweeters descended onto Mastodon in ever increasing waves each day. To the Twitter people it feels like a confusing new world, whilst they mourn their old life on Twitter. They call themselves "refugees", but to the Mastodon locals it feels like a busload of Kontiki tourists just arrived, blundering around yelling at each other and complaining that they don't know how to order room service. We also mourn the world we're losing.

[...]

I was a reasonably early user of Twitter, just as I was a reasonably early user of Mastodon. I've met some of my firmest friends through Twitter, and it helped to shape my career opportunities. So I understand and empathise with those who have been mourning the experience they've had on Twitter — a life they know is now over. But Twitter has slowly been rotting for years — I went through that grieving process myself a couple of years ago and frankly don't really understand what's so different now compared to two weeks ago.

There's another, smaller group of people mourning a social media experience that was destroyed this week — the people who were active on Mastodon and the broader fediverse prior to November 2022. The nightclub has a new brash owner, and the dancefloor has emptied. People are pouring in to the quiet houseparty around the corner, cocktails still in hand, demanding that the music be turned up, walking mud into the carpet, and yelling over the top of the quiet conversation.

All of us lost something this week. It's ok to mourn it.

Source: Home invasion | Hugh Rundle

Image: Joshua Sukoff

Second-order effects of widespread AI

Sometimes ‘Ask HN’ threads on Hacker News are inane or full of people just wanting to show off their technical knowledge. Occasionally, though, there’s a thread that’s just fascinating, such as this one about what might happen once artificial intelligence is widespread.

Other than the usual ones about deepfakes, porn, and advertising (all which should concern us) I thought this comment by user ‘htlion’ was insightful:

AI will become the first publisher of contents on any platform that exists. Will it be texts, images, videos or any other interactions. No banning mechanisms will really help because any user will be able to copy-paste generated content. On top of that, the content will be generated specifically for you based on "what you like". I expect a backlash effect where people will feel like becoming cattle which is fed AI-generated content to which you can't relate. It will be even worse in the professional life where any admin related interaction will be handled by an AI, unless you are a VIP member for this particular situation. This will strengthen the split between non-VIP and VIP customers. As a consequence, I expect people to come back to localilty, be it associations, sports clubs or neighborhood related, because that will be the only place where they will be able to experience humanity.Source: What will be the second order effects widespread AI? | Hacker News

Hyperbolic discounting applied to habit-formation

We live near the middle of town, a five minute walk to the leisure centre — and less than that to get to the shops. As a result, we don’t use our cars at all for three days of the week, and I go to the gym at the leisure centre every day.

My grandmother, who wasn’t well-off and who rented all her life, used to ensure that she lived right next to a bus stop. Although she wouldn’t have used the phrase from this article, she knew that she was more likely to travel and get places that way!

You may have heard of hyperbolic discounting from behavioral economics: people will generally disproportionally, i.e. hyperbolically, discount the value of something the farther off it is. The average person judges $15 now as equivalent to $30 in 3-months (an annual rate of return of 277%!).Source: Hyperbolic Distance Discounting | Atoms vs Bits[…]

But what about when something is farther off in space rather than time?

Say a 1-hour activity is 10 minutes away, compared to 5 minutes away. The total time usage would be 80 vs 70 minutes, about 15% longer. A linear model would predict that it would feel 15% more costly, and then proportionally affect your likelihood of going. In practice though, an extra 10 or 20 minutes of travel time will somehow frequently nudge you into non-participation.

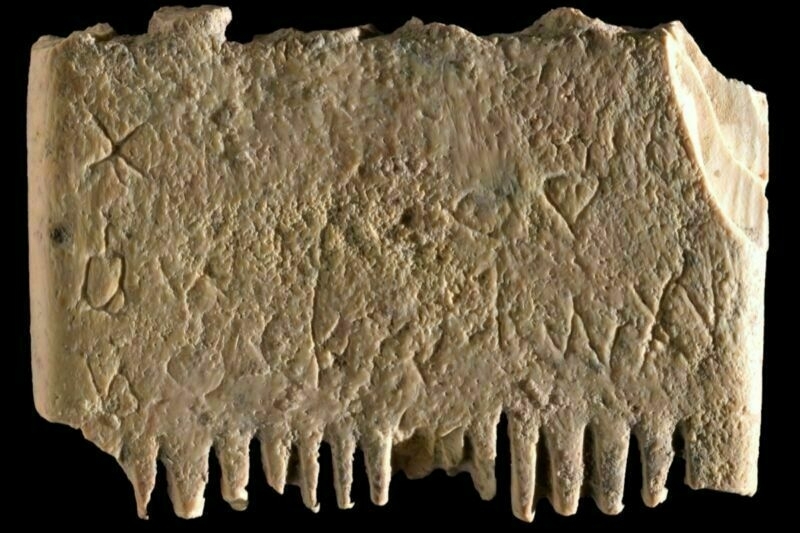

The (surprising) oldest full sentence in the Canaanite language in Israel

Apparently this comb has an inscription on it which reads “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” It was made from an imported elephant tusk!

The comb measures just 3.5 by 2.5 centimeters (roughly 1.38 by 1 inches), with teeth on both sides, although only the bases remain; the rest of the teeth were likely broken long ago. One side had thicker teeth, the better to untangle knots, while the other had 14 finer teeth, likely used to remove lice and their eggs from beards and hair. Further analysis showed noticeable erosion at the comb's center, which the authors believe was likely due to someone's fingers holding it there during use.Source: Ancient wisdom: Oldest full sentence in first alphabet is about head lice | Ars TechnicaThe authors also used X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and digital microscopy to confirm that the comb is made of ivory from an elephant tusk, suggesting it was imported. The team sent a sample from the comb to the University of Oxford’s radiometric laboratory, but the carbon was too poorly preserved to accurately date the sample.

The inscription consists of 17 letters (two damaged) that together form a complete seven-word sentence. The letters aren’t well-aligned, per the authors, nor are they uniform in size; the letters become progressively smaller and lower in the first row, with letters running from right to left. When whoever engraved the comb reached the edge, they turned it 180 degrees and engraved the second row from left to right. The engraver actually ran out of room on the second row, so the final letter is engraved just below the last letter in that row. Still, said engraver had to be fairly skilled, given the small size of the lettering.

Rituals for moving jobs when working from home

Terence Eden reflects on changing jobs when working from home and how… weird it can be. While I’ve been based from two different converted garages during the past decade, I’ve travelled a lot so it has felt different.

I can imagine, though, if that’s not the case, it can all feel a little bit discombobulating!

One Friday last year, I posted some farewell messages in Slack. Removed myself from a bunch of Trello cards. Had a quick video call with the team. And then logged out of my laptop. I walked out of my home office and sat in my garden with a beer.Source: Job leaving rituals in the WFH era | Terence Eden’s BlogThe following Monday I opened the door to the same office. I logged in to the same laptop. I logged into a new Slack - which wasn’t remarkably different from the old one. Signed in to a new Trello workspace - ditto. And started a video call with my new team.

I’ll admit, It didn’t feel like a new job!

There was no confusing commute to a new office. No having to work out where the toilets and fire exits were. No “here’s your desk - it’s where John used to sit, so people might call you John for a bit”. I didn’t even have to remember people’s names because Zoom showed all my colleagues' names & job titles.

There was no waiting in a liminal space while receptionists worked out how to let me in the building.

In short, there was no meaningful transition for me.

Decentralisation begins at decentring yourself

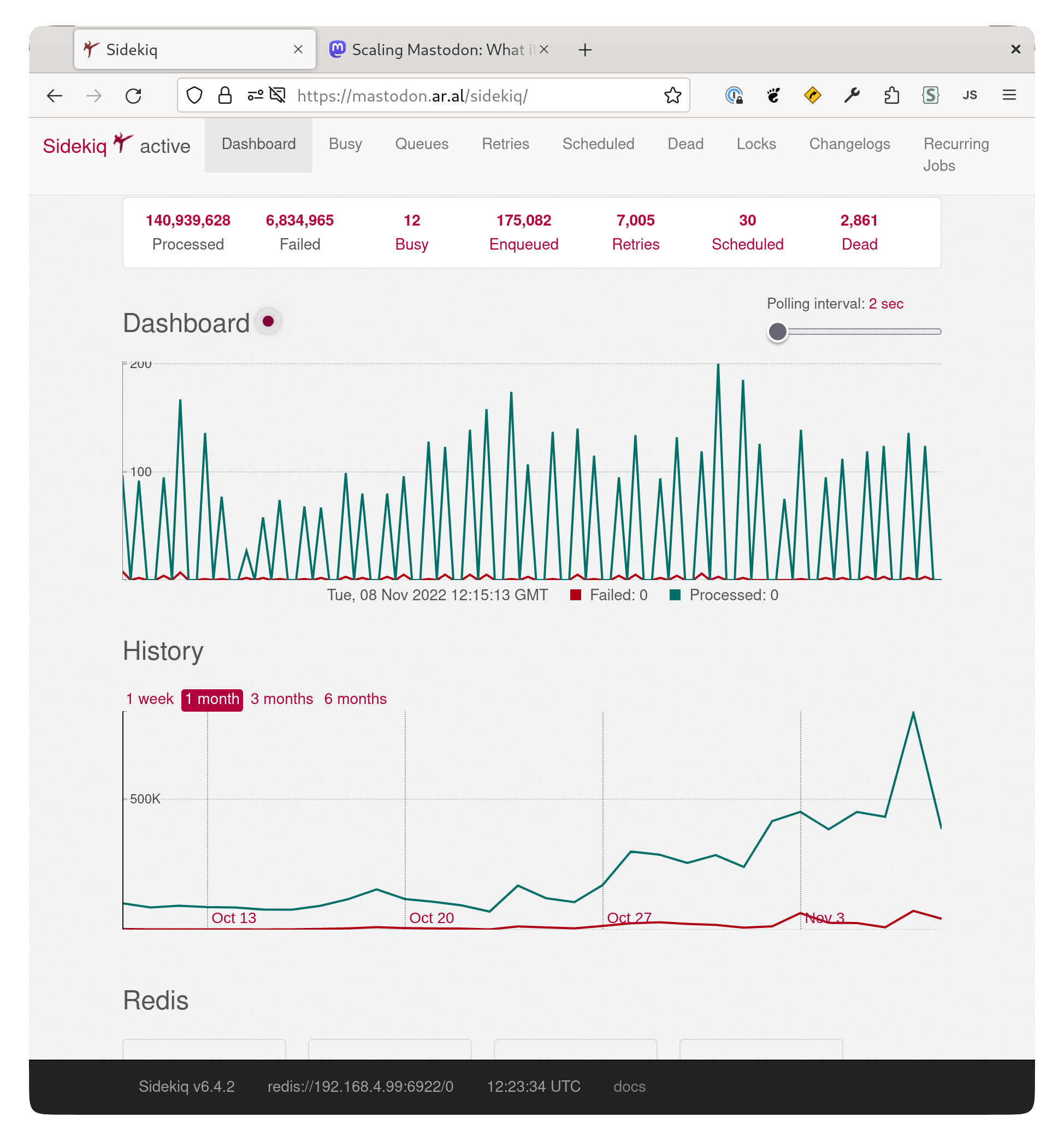

Aral Balkan, who has 22,000 followers on the Fediverse and who recently had a birthday, has written about the influx of people from Twitter. As I’ve found, especially on my personal blog, you can essentially run a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack on yourself by posting a link to your blog to the Fediverse. As each server pings it, the server can eventually buckle under the weight.

What follows is a really useful post in terms of Aral’s journey towards what he calls the ‘Small Web’. While I don’t necessarily agree that we should all have our own instances, I do think it’s useful for organisations of every size to run them.

If Elon Musk wanted to destroy mastodon.social, the flagship Mastodon instance, all he’d have to do is join it.Thank goodness Elon isn’t that smart.

I jest, of course… Eugen would likely ban his account the moment he saw it. But it does illustrate a problem: Elon’s easy to ban. Stephen, not so much. He’s a national treasure for goodness’ sake. One does not simply ban Stephen Fry.

And yet Stephen can similarly (yet unwittingly) cause untold expense to the folks running Mastodon instances just by joining one.

The solution, for Stephen at least, is simple: he should run his own personal instance.

(Or get someone else to run it for him, like I do.)

Running his own instance would also give Stephen one additional benefit: he’d automatically get verified.

After all, if you’re talking to, say, @stephen@social.stephenfry.com, you can be sure it’s really him because you know he owns the domain.

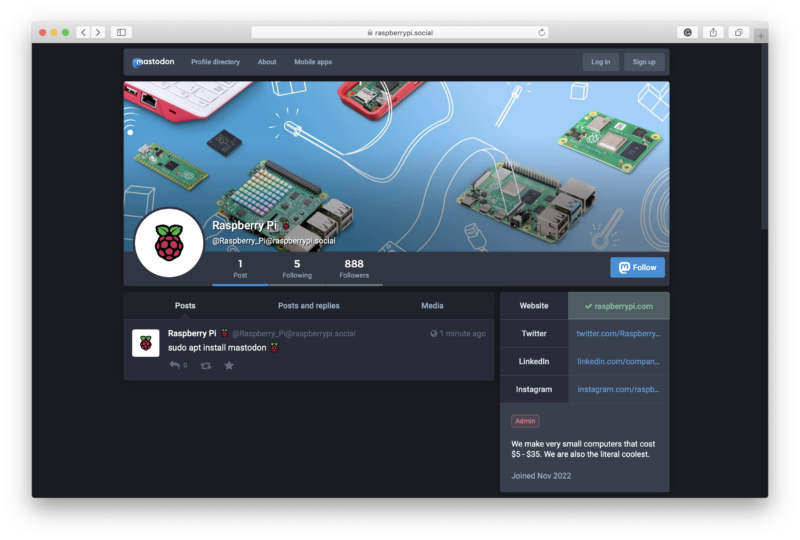

Organisations are not just joining the Fediverse, they're setting up their own instances

It’s great to see that Raspberry Pi Ltd. and other organisations are setting up their own servers. Not only does it enable them to verify themselves, but that of their employees and affiliates really easily.

I’m sure it won’t all be smooth sailing ahead for the Fediverse, especially when it comes to trust and verification. But I’m optimistic that the recent migration from Twitter is ultimately for the good of the human species.

We’ve opted to host our own instance. We’ve done this because, with multiple instances out there, we had to decide how to make sure people following us knew that our Raspberry Pi account was the “real” one.Source: An escape pod was jettisoned during the fighting | Raspberry PiDistributed systems are an interesting corner case when it comes to trust. Because when it comes to identity, you eventually have to trust someone. Whether that’s a corporation, like Twitter, or a government, or the person themselves. Trust is needed.

With Mastodon the root of trust for identity is the admin of the instance you’re on, and the admins on all the other instances, where you’re trusting them to remove “fake” accounts. Or, if you’re running your own instance, then it’s the domain name registrars. The details of our domain registration of the

raspberrypi.socialdomain may be redacted for privacy, but our domain registrar knows who we are, and is the same registrar we use for all our other domains. They trust our government-issued identity to prove that we are Raspberry Pi Ltd. You can trust them, they trust the government, and ultimately the government trusts us because they can use Ultima Ratio Regum, the last argument of kings.

A cluttered desk is a sign of genius

Perhaps it's because I'm not a designer like the author of this post, but organising your desk space like this leaves me cold. My space looks like this.

I’m proud of what I’ve done with my desk setup over the last five years. Through careful observation of what’s working and what’s not, I’ve continued to improve how it serves my creative pursuits. Still, when I look at it in the morning, I get a rush of creative energy and optimism.

Source: The Evolution of the Desk Setup | Arun

Quotation-as-title comes from a plaque my father had on his (spectacularly untidy) desk...

Decentralising online learning

A “technical presentation that is structured and designed for a non-technical audience” by Stephen Downes. With the Twitter lifeboats again being deployed, this is a timely look at how federated and decentralised technologies can be used for removing the silos from online learning.

Source: Open Learning in the Fediverse | Stephen DownesAs a new generation of digital technologies evolves we are awash in new terms and concepts: the metaverse, the fediverse, blockchain, web3, acitivitypub, and more. This presentation untangles these concepts and presents them from the perspective of their impact on open learning.

Presenteeism, overwork, and being your own boss

I spend a lot of time on the side of football pitches and basketball courts watching my kids playing sports. As a result, I talk to parents and grandparents from all walks of life, who are interested in me being a co-founder of a co-op — and that, on average, I work five-hour days.

This wasn’t always the case, of course. I’ve been lucky, for sure, but also intentional about the working life I want to create. And I’m here to tell you that unless you at least partly own the business you work for, you’re going to be overworking until the end of your days.

Hidden overwork is different to working long hours in the office or on the clock at home – instead, it’s the time an employee puts into tasks on top of their brief. There are plenty of reasons people take on this extra work: to be up to speed in meetings; appear ‘across issues’ when asked about industry developments; or seem sharp in an environment in which a worker is still trying to establish themselves.Source: The hidden overwork that creeps into so many jobs | BBC WorklifeThere are myriad ways a person’s day job can slip into their non-working hours: think a worker chatting to someone from their industry at their child’s birthday party, and suddenly slipping into networking mode. Or perhaps an employee hears their boss mention a book in a meeting, so they download and listen to it on evening walks for a week, stopping occasionally to jot down some notes.

[…]

However, for many, this overwork no longer feels like a choice – and that’s when things go bad. This can especially be the case, says [Alexia] Cambon [director of research at workplace-consultancy Gartner’s HR practice], when these off-hours tasks become another form of presenteeism – for instance, an employee reading a competitor’s website and sharing links in a messaging channel at night, just so they can signal to their boss they’re always on. “We’re seeing… more employees who feel monitored by their organisations, and then feel like they have to put in extra hours,” she says.

As such, this hidden overwork can do a lot of potential damage if it becomes an unspoken requirement. “If there’s more expectation and burden associated with it, that’s where people are going to have negative consequences,” says Nancy Rothbard, management professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, US. “That’s where it becomes tough on them.”

Hyperfinancialisation has taken over UK politics

I’m reading This Could Be Our Future by (Kickstarter co-founder) Yancey Strickler at the moment. It rails against hyperfinancialisation and then provides a way of thinking about the world differently.

As this opinion piece in The Guardian points out, we need a way of thinking about politics and the market which isn’t driven (literally!) by investment bankers.

Rishi Sunak’s first job was at the US investment bank Goldman Sachs. He went on to spend 14 years in the sector before becoming an MP. In many ways, his unelected appointment marks the highpoint of big finance’s takeover of Britain’s political and economic system – a quiet infiltration of Westminster and Whitehall has been taking place over several decades and gone largely unremarked.Source: With Rishi Sunak, the City’s takeover of British politics is complete | Aeron Davis[…]

Looking at the coalition government, every senior figure who managed Treasury economic policy – George Osborne, Danny Alexander, David Cameron, Rupert Harrison, John Kingman and Nick Macpherson – later gained well-paid positions in the financial sector. And three of the last five chancellors have come from the sector. Jeremy Hunt’s current advisers all come from investment banking.

This matters because investment bankers have very little to do with the real economy that ordinary people inhabit. They don’t run businesses. They don’t deal with actual product and customer markets. Their work is confined to financial markets, aiding corporate financial manoeuvres, and trading and managing their own financial assets. Their primary aim is to make profits from such activities, regardless of how it affects the real economy, the national interest or employees. If that means shorting the pound or breaking up a successful company for quick profits, then so be it.

[…]

And an overpowered financial sector has certainly not been conducive to good governance, either. There’s nothing democratic about extensive public service cuts being used to pay for saving the private banking sector, as in the aftermath of the 2008 crash, or the bond markets determining the credibility of governments, or the fact that the bankers and hedge funds are the biggest single source of Conservative party donations. Nor is trust in British democracy likely to be enhanced by a super-rich PM who has allegedly avoided taxes and made a fortune as a financier at the nation’s cost.

An anarchist take on the Twitter acquisition

I’m quoting this liberally, as it’s excellent. I was on Twitter from almost when it began in January 2007 through to late 2021 and the journey from protest tool to toy of plutocrats has been brutal.

What if Trump had been able to make common cause with a critical mass of Silicon Valley billionaires? Would things have turned out differently? This is an important question, because the three-sided conflict between nationalists, neoliberals, and participatory social movements is not over.Source: The Billionaire and the Anarchists: Tracing Twitter from Its Roots as a Protest Tool to Elon Musk’s Acquisition | CrimethIncTo put this in vulgar dialectical terms:

Understood thus, Musk’s acquisition of Twitter is not just the whim of an individual plutocrat—it is also a step towards resolving some of the contradictions within the capitalist class, the better to establish a unified front against workers and everyone else on the receiving end of the violence of the capitalist system. Whatever changes Musk introduces, they will surely reflect his class interests as the world’s richest man.

- Thesis: Trump’s effort to consolidate an authoritarian nationalism

- Antithesis: opposition from neoliberal tycoons in Silicon Valley

- Synthesis: Elon Musk buys Twitter

[…]

[I]nnovative models do not necessarily emerge from the commercial entrepreneurism of the Great Men of history and economics. More often, they emerge in the course of collective efforts to solve one of the problems created by the capitalist order. Resistance is the motor of history. Afterwards, opportunists like Musk use the outsize economic leverage that a profit-driven market grants them to buy up new technologies and turn them definitively against the movements and milieux that originally produced them.

[…]

Musk claims that his goal is to open up the platform for a wider range of speech. In practice, there is no such thing as “free speech” in its pure form—every decision that can shape the conditions of dialogue inevitably has implications regarding who can participate, who can be heard, and what can be said. For all we might say against them, the previous content moderators of Twitter did not prevent the platform from serving grassroots movements. We have yet to see whether Musk will intentionally target activists and organizers or simply permit reactionaries to do so on a crowdsourced basis, but it would be extremely naïve to take him at his word that his goal is to make Twitter more open.

[…]

Effectively, Musk’s acquisition of Twitter returns us to the 1980s, when the chief communications media were entirely controlled by big corporations. The difference is that today’s technologies are participatory rather than unidirectional: rather than simply seeing newscasters and celebrities, users see representations of each other, carefully curated by those who run the platforms. If anything, this makes the pretensions of social media to represent the wishes of society as a whole more insidiously persuasive than the spectacles of network television could ever be.

[…]

It’s you against the billionaires. At their disposal, they have all the wealth and power of the most formidable empire in the history of the solar system. All you have going for you is your own ingenuity, the solidarity of your comrades, and the desperation of millions like you. The billionaires succeed by concentrating power in their own hands at everyone else’s expense. For you to succeed, you must demonstrate ways that everyone can become more powerful. Two principles confront each other in this contest: on one side, individual aggrandizement at the expense of all living things; on the other, the potential of the individual to increase the self-determination of all human beings, all living creatures.

Twitter the disaster clown car company

I didn’t forsee Elon Musk buying Twitter when I deactivated my verified account about a year ago. But it was already an algorithmic hellscape.

As this article points out, Big Tech no longer really does very interesting stuff technically. It’s all about the politics these days.

[T]he problems with Twitter are not engineering problems. They are political problems. Twitter, the company, makes very little interesting technology; the tech stack is not the valuable asset. The asset is the user base: hopelessly addicted politicians, reporters, celebrities, and other people who should know better but keep posting anyway. You! You, Elon Musk, are addicted to Twitter. You’re the asset. You just bought yourself for $44 billion dollars.Source: Welcome to hell, Elon | The Verge[…]

[Y]ou can write as many polite letters to advertisers as you want, but you cannot reasonably expect to collect any meaningful advertising revenue if you do not promise those advertisers “brand safety.” That means you have to ban racism, sexism, transphobia, and all kinds of other speech that is totally legal in the United States but reveals people to be total assholes. So you can make all the promises about “free speech” you want, but the dull reality is that you still have to ban a bunch of legal speech if you want to make money. And when you start doing that, your creepy new right-wing fanboys are going to viciously turn on you, just like they turn on every other social network that realizes the same essential truth.

[…]

The essential truth of every social network is that the product is content moderation, and everyone hates the people who decide how content moderation works. Content moderation is what Twitter makes — it is the thing that defines the user experience. It’s what YouTube makes, it’s what Instagram makes, it’s what TikTok makes. They all try to incentivize good stuff, disincentivize bad stuff, and delete the really bad stuff. Do you know why YouTube videos are all eight to 10 minutes long? Because that’s how long a video has to be to qualify for a second ad slot in the middle. That’s content moderation, baby — YouTube wants a certain kind of video, and it created incentives to get it. That’s the business you’re in now. The longer you fight it or pretend that you can sell something else, the more Twitter will drag you into the deepest possible muck of defending indefensible speech. And if you turn on a dime and accept that growth requires aggressive content moderation and pushing back against government speech regulations around the country and world, well, we’ll see how your fans react to that.

Image: DALL-E 2

AI is coming for middle management

It’s hard not to agree with this. Things may play out a little different in the EU, but in the USA and UK I can foresee the middle classes despairing.

Legacy businesses will have to rely on retail and hourly support staff to be able to reduce management head count as a means of freeing up money for implementing automation. In order to do that, they will need to implement AI management tools; chat bots, scheduling, negotiating, training, data collection, diagnostic analysis, etc., before hand.Source: AI will replace middle management before robots replace hourly workers | Chatterhead SaysOtherwise, they will be left to rely on an overly bureaucratic and entrenched middle management layer to do so and that solution is likely to come from outsourcing or consultants. All the while, the retail environment deteriorates as workers are tasked to replace themselves without any additional benefits; service declines, implementation falters, costs go up, more consulting required.

Union formation across the retail landscape will force corporations to reduce management head count and implement AI management solutions which focus on labor relations. The once fungible and disposable retail worker will be transformed into a highly sought after professional who will be relied upon specifically for automation implementation.

Image: DeepMind

Being 'quietly fired' at work

I’ll not name the employer, and this wasn’t recent, but I’ve been ‘quietly fired’ from a job before. I never really knew why, other than a conflict of personalities, but there was no particular need for pursuing that path (instead of having a grown-up conversation) and it definitely had an impact on my mental health.

I think part of the reason this happens is because a lot of organisations have extremely poor HR functions and managers without much training. As a result, they muddle through, avoiding conflict, and causing more problems as a result.

There may not always be a good fit between jobs and the workers hired to do them. In these cases, companies and bosses may decide they want the worker to depart. Some may go through formal channels to show employees the door, but others may do what Eliza’s boss did – behave in such a way that the employee chooses to walk away. Methods may vary; bosses may marginalise workers, make their lives difficult or even set them up to fail. This can take place over weeks, but also months and years. Either way, the objective is the same: to show the worker they don’t have a future with the company and encourage them to leave.Source: The bosses who silently nudge out workers | BBC WorklifeIn overt cases, this is known as ‘constructive dismissal’: when an employee is forced to leave because the employer created a hostile work environment. The more subtle phenomenon of nudging employees slowly but surely out of the door has recently been dubbed ‘quiet firing’ (the apparent flipside to ‘quiet quitting’, where employees do their job, but no more). Rather than lay off workers, employers choose to be indirect and avoid conflict. But in doing so, they often unintentionally create even greater harm.

[…]

An employee subtly nudged out the door isn’t without legal recourse, either. “If you were to look at each individual aspect of quiet firing, there’s likely nothing serious enough to prove an employer breach of contract,” says Horne. “However, there’s the last-straw doctrine: one final act by the employer which, when added together with past behaviours, can be asserted as constructive dismissal by the employee.”

More immediate though, is the mental-health cost to the worker deemed to be expendable by the employer – but who is never directly informed. “The psychological toll of quiet firing creates a sense of rejection and of being an outcast from their work group. That can have a huge negative impact on a person’s wellbeing,” says Kayes.