Monday morning feeling

This is definitely a mood.

Just a cat pondering the meaning of life.Source: Who the Hell Are You? | The New Yorker

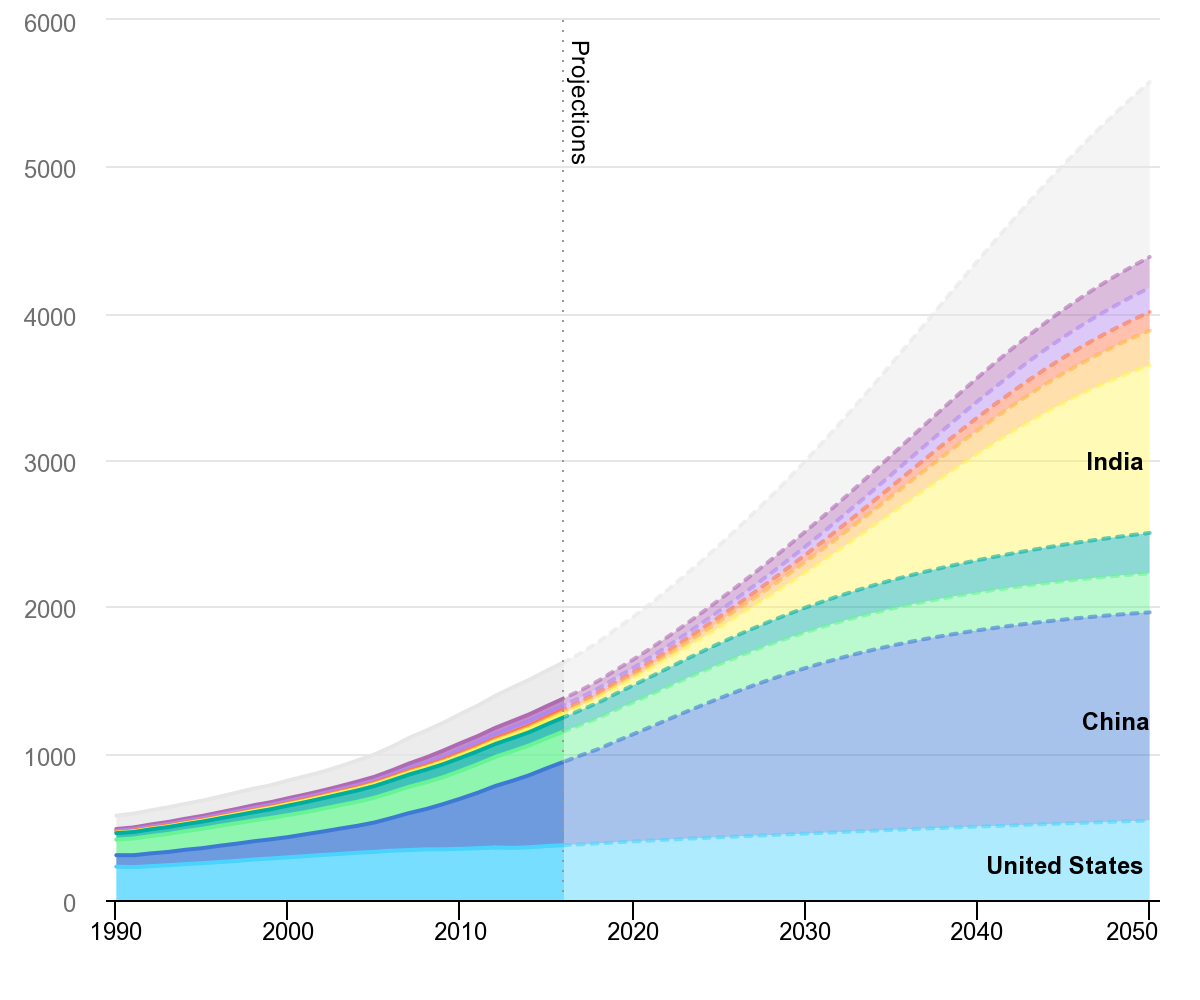

The burnout curve

I stumbled across this on LinkedIn. There doesn't seem to be an authoritative source yet other than the author's (Nick Petrie) social media posts, which is a shame. So I'm quoting most of it here so I can find and refer to it in future.

In terms of my own experience, I slid down that slope pretty quickly in my teaching career, and definitely experienced the 'trap' of going back into a similar situation in a different school. It was also toxic as I had been promoted quickly and, looking back, probably beyond my abilities and experience at the time.

But the great thing about this graphic is that it shows that it's possible to dig your way out, as I did, by realising that a different path is possible. It hasn't always been plain sailing, and there have been other, lesser, traumas since. But I've definitely grown from my earlier experiences, and this is a handy chart to show people who are near the bottom of the curve.

When we interviewed people who had burned out, they told us remarkably similar stories.1. A relentless work ethic – they had a set of beliefs and stories that drove them to work hard - I will deliver, I won’t let people down, I must give 100% at all times.2. Bottomless workload – they joined organizations that rewarded their work ethic with endless work. The harder they worked the more they were given.3. Sliding into burnout – thoughts of work became constant. They had trouble switching off in the evenings, work was taking over their life.4. Ignoring the warning signs – their body was sending signals that something needed to change. They were tense, irritated, exhausted. But they couldn’t slow down – there was too much to do.5. The breakdown – For those who would not listen, the body and brain had a last resort. They shut down. People couldn’t get out of bed, couldn’t drive, couldn’t read. The body refused to go on.The trap for many people is the belief that rest is the solution. So, they took a break – a week, a month or a year. They then went back to the same work, with the same mindset and the same behaviors. They got the same result.The people we interviewed who genuinely overcame burnout followed a common path.6. Meeting friends and mentors – they realized they couldn’t repeat their past. They needed new perspectives and a new approach. They got these from family, peers, coaches, therapists and support groups.7. Deep reflection – they came off autopilot for the first time in years. They reflected deeply on the past – what caused me to burnout? What was driving me? Then the future – what sort of work and life do I want going forward? How can I move myself towards this vision?8. Taking action – they took new actions, sometimes big – change of job, change of career - sometimes small - they set new boundaries, restarted a hobby, got a therapist. Some things helped, some things did not. It didn’t matter. The key thing was they were doing NEW things. They were not repeating their old habits. New actions led to new insights and habits.9. Post traumatic growth – when we interviewed people who took this path 2 years after their burnout, the most surprising thing was how much they had grown from the experience.

Source: Nick Petrie | LinkedIn

Status detection systems

I listened to a fascinating episode of the You Are Not So Smart podcast while out running over the weekend. The focus was on a new book by Will Storr called The Status Game and he was full of insights.

- Some of the most important takeaways for me were around:

- There are three main status games: dominance, virtue, and success

- Status games are hard wired into us, and we're essentially just 'status detection systems'

- Social media sites such as Twitter make it easy to signal virtue, whereas those such as Instagram make it easy to signal success.

- Trying to force people to play your type of status game is about dominance.

- Status games are why teenagers, who are new to these games, get embarrassed easily and take lots of risks.

- The types of status games available to you often depend on your socio-economic status. This explains honour killings, quests for dominance, etc.

In this episode we welcome back author Will Storr whose new book, The Status Game, feels like required reading for anyone confused, curious, or worried about how politics, cults, conspiracy theories communities, social media, religious fundamentalism, polarization, and extremism are affecting us – everywhere, on and offline, across cultures, and across the world.Source: The game we can’t escape, the psychology behind our perpetual drive to pursue status | You Are Not So SmartWhat is The Status Game? It’s our primate propensity to perpetually pursue points that will provide a higher level of regard among the people who can (if we provoked such a response) take those points away. And deeper still, it’s the propensity to, once we find a group of people who regularly give us those points, care about what they think more than just about anything else.

In the interview, we discuss our inescapable obsession with reputation and why we are deeply motivated to avoid losing this game through the fear of shame, ostracism, embarrassment, and humiliation while also deeply motivated to win this game by earning what will provide pride, fame, adoration, respect, and status.

The punishment for being authentic is becoming someone else’s content

This short piece by Drew Austin reminds me of a couple of links I posted yesterday about Non-places and TikTok’s effect on migration. There are so many quotable parts, including that when it comes to social media, “the only place left to go is outside”.

What I think is interesting is how online and offline used to be seen as completely separate. Then we realised the impact that offline life had on online life, and now we’re seeing the reverse: Instagram, TikTok, etc. having a huge impact on the spaces in which we exist offline.

“In the next few years,” Kyle Chayka tweeted yesterday, “the last desperate search for shreds of authentic local culture will convulse the globe as the internet consumes every interesting quirk and scales it up to the size of TikTok.” That all-too-plausible prediction fits well alongside Chayka’s concept of AirSpace and his observations about overtourism, each examining how social media has come to shape the physical world (or at least vent its noxious exhaust there) instead of merely reflecting it. If AirSpace represents the homogenizing tendency of globally scaled algorithmic platforms like Instagram and Airbnb, which herd everything they touch into aesthetic alignment, then TikTok’s impact seems like the opposite: the cultivation and amplification of difference by a desperate horde of content creators scouring the ends of the earth for new material. The latter ultimately has the same entropic effect as the former, reframing local nuances as temporary viral microtrends that diffuse through culture, form the basis for a thinkpiece or two, and then recede back to their original modest scale. This may be ephemeral but it is pervasive and ongoing. In the contemporary landscape, the punishment for being authentic is becoming someone else’s content.Source: I’m Beginning to See the Light | Kneeling Bus[…]

The illusion that the internet and “real life” are two separate universes has been thoroughly dispelled by now, but the nature of their interaction is complex and evolving. The social media era seems to have already peaked, as I predicted at the end of last year, calling our present moment a “saturation point of cultural self-consciousness that represents the fullest possible synthesis of reality and our digitally mediated perception of it.” The metaverse concept was dead on arrival; there’s nowhere left to go but outside. And that’s what we’re doing: TikTok is the social network for the internet’s decadent era, embodying the worldview that becoming viral content is the highest calling, the end state to which everything aspires and strives. You visit Italy not to enjoy yourself but to help Italy fulfill its destiny as a meme.

Job crafting, identity, and fulfilment

This article by Lan Nguyen Chaplin, a professor of marketing at a prestigious business school, reflects my own experience. Those jobs I’ve thought were ‘big’ and ‘important’ have been the ones that have drained me of energy, made me sad, and generally changed me for the worse.

Instead, as Chaplin says, the important thing is to align your work your values and personal strengths. This (eventually) allows you to transform what you do into a sustainable, balanced, and purposeful career. Sometimes, though, you have to know what you’re willing to tolerate and what you’re not, which can involve going precipitously close to the fire.

Outside of my fancy new title, I had begun to feel empty. In just a few months, my identity had quite literally become “my job” and I lost sight of the many things that fulfilled me outside of it. I didn’t have time or energy for family and friends. Activities that brought me joy, like running and lacrosse, went out the window. I traveled for work instead of pleasure. I had no time to give back to my community.Source: What You Should Chase Instead of a Dream Job | AscendInstead, I jotted down research ideas on bar napkins, replied to emails when everyone else was offline, and had a growing portfolio of projects in development. I didn’t know how to disconnect without feeling unproductive. For hours, I sat with my laptop in isolation, working on research that might never be published.

[…]

The moment you have found your dream job is the moment you have stopped growing, evolving, and finding new ways to experience joy in your role. Remember, you were hired because you offer something the organization is missing. They need change. They need you to bring your whole self to work, and that means doing things differently with the added flare that is you. A job that inspires you and gives you the space you need to be your full self is the dreamiest job out there.

AI writing detectors don’t work

If you understand how LLMs such as ChatGPT work then it’s pretty obvious that there’s no way “it” can “know” anything. This includes being able to spot LLM-generated text.

This article discusses OpenAI’s recent admission that AI writing detectors are ineffective, often yielding false positives and failing to reliably distinguish between human and AI-generated content. They advise against the use of automated AI detection tools, something that educational institutions will inevitably ignore.

In a section of the FAQ titled "Do AI detectors work?", OpenAI writes, "In short, no. While some (including OpenAI) have released tools that purport to detect AI-generated content, none of these have proven to reliably distinguish between AI-generated and human-generated content."Source: OpenAI confirms that AI writing detectors don’t work | Ars Technica[…]

OpenAI’s new FAQ also addresses another big misconception, which is that ChatGPT itself can know whether text is AI-written or not. OpenAI writes, “Additionally, ChatGPT has no ‘knowledge’ of what content could be AI-generated. It will sometimes make up responses to questions like ‘did you write this [essay]?’ or ‘could this have been written by AI?’ These responses are random and have no basis in fact.”

[…]

As the technology stands today, it’s safest to avoid automated AI detection tools completely. “As of now, AI writing is undetectable and likely to remain so,” frequent AI analyst and Wharton professor Ethan Mollick told Ars in July. “AI detectors have high false positive rates, and they should not be used as a result."

Microcast #096 — Getting back in the saddle

Explaining what I've been up to and the difference between being a hedgehog and a fox.

Show notes

- The Hedgehog and the Fox by Isaiah Berlin

- We Are Open Co-op

- The role of endorsement in Open Badges and Open Recognition

Image: Pexels

Non-places

I’m a big fan of Guy Debord’s work but have never read that of Marc Augé, who came up with the concept of ‘non-places’. These are spaces like airports and hotels where human interaction is largely transactional, leading to a form of psychic isolation.

This article outlines Augé argument that to counteract the dehumanising effects of these non-places, individuals should engage in active observation, storytelling, and even talking to strangers. In this way we essentially become ‘supermodern flaneurs’, restoring a social element to these otherwise isolating spaces.

Augé was keen to explain how the transformations of the contemporary world had made anthropology more complicated. “We are in an era characterized by changes of scale,” he wrote. “Images of all sorts, relayed by satellites and caught by the aerials that bristle on the roofs of our remotest hamlets, can give us an instant, sometimes simultaneous vision of an event taking place on the other side of the planet.” So far, so postmodern; what Augé called the “acceleration” of events is an idea that crops up repeatedly in political theory. The specifically supermodern condition that he identifies is the dominance of non-places.Source: Non-places are robbing us of life | UnHerdWe live in “a world where people are born in the clinic and die in hospital, where transit points and temporary abodes are proliferating under luxurious or inhuman conditions” — from “hotel chains and squats, holiday clubs and refugee camps”. In non-places, exchange between human beings is transactional: you buy a sandwich, or a massage, or a train ticket. Speech is replaced by text; signs direct behaviour, instead of people, giving instructions and advertising products. We are, therefore, isolated, in “a solitude made all the more baffling by the fact that it echoes millions of others”.

TikTok's algorithm and its effect on migration

Kukes, Albania is one of the poorest cities in Europe. Since the end of pandemic lockdowns, the city has seen a sharp rise in the number of Albanians, especially men, seeking asylum in the UK.

This article is a real eye-opener as to what’s going on, and talks about everything from TikTok propaganda to criminal gangs and cannabis houses. Well worth a read, especially to show the other side of the “small boats” rhetoric.

In 2022, the number of people leaving Albania for the U.K. ticked up dramatically, as well as the number of those seeking asylum, at around 16,000, more than triple the previous year. According to the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, one reason for the uptick in claims may be that Albanians who lack proper immigration status are more likely to be identified, leading them to claim asylum in order to delay being deported. But Albanians claiming asylum are also often victims of blood feuds — long-standing disputes between communities, often resulting in cycles of revenge — and viciously exploitative trafficking networks that threaten them and their families if they return to Albania.Source: The Albanian town that TikTok emptied | Coda StoryBy 2022, Albanian criminal gangs in Britain were in control of the country’s illegal marijuana-growing trade, taking over from Vietnamese gangs who had previously dominated the market. The U.K.’s lockdown — with its quiet streets and newly empty businesses and buildings — likely created the perfect conditions for setting up new cannabis farms all over the country. During lockdown, these gangs expanded production and needed an ever-growing labor force to tend the plants — growing them under high-wattage lamps, watering them and treating them with chemicals and fertilizers. So they started recruiting.

Everyone in Kukes remembers it: The price of passage from Albania to the U.K. on a truck or small boat suddenly dropped when Covid-19 restrictions began to ease. Before the pandemic, smugglers typically charged 18,000 pounds (around $22,800) to take Albanians across the channel. But last year, posts started popping up on TikTok advertising knock-down prices to Britain starting at around 4,000 pounds (around $5,000).

People in Kukes told me that even if they weren’t interested in being smuggled abroad, TikTok’s algorithm would feed them smuggling content — so while they were watching other unrelated videos, suddenly an anonymous post advertising cheap passage to the U.K. would appear on their “For You” feed.

Walking 1,000 miles across Europe

As I know from personal experience, walking a long way by yourself is hard work, both mentally and physically. As this article points out, doing so as a woman is even harder, so good on Lea Page for not only walking a thousand miles across Europe, but writing about how the biggest danger is… men.

When I walk alone, the consequences of every good or bad choice I make fall entirely on me: a responsibility and a freedom. As a woman and a mother, I rarely only have to consider what I want and need without having to first attend to other people. I know there are risks, but each time I come out of that “forest”, I feel stronger and more confident. Weighed against the simple daily rhythms of a long-distance walk and the joy and wonder I experience, risk – reasonable risk – becomes a small part of the equation, and one I am willing to accept.Source: I walked 1,000 miles alone through Europe – and learned that fear is the price of freedom | The Guardian[…]

One other time, while walking along a river just outside Colle di Val D’Elsa in Tuscany, I felt that familiar clench of panic. This river, a glacial robin’s-egg blue, meandered and tumbled gently. The gorge was not deep, but a lonely wooded path just outside a city struck me as the perfect place for an ambush. Clearly, men exist everywhere, so it made no sense to be frightened in that one particular place. I knew that, statistically, women are safer out in the world than they are at home, but in that moment, knowledge felt like thin protection. Unable to shake my feelings of dread, I called my husband, and we talked about inconsequential things so I could hear his sleepy voice and keep putting one foot in front of another.

And that’s what women are really talking about when we talk about being afraid. We are talking about men. But there is, I learned, a difference between being afraid and being unsafe.

Cooling down is hotting up

As the world heats up, humans are going to need to cool down. The use of air conditioning already accounts for nearly 20% of electricity used in buildings worldwide, so this report highlights the urgent need for higher efficiency standards in cooling technologies to mitigate the strain on energy systems and reduce emissions.

Apparently, effective policies could halve future energy demand and cut costs by $3 trillion by 2050. More importantly than the financial impact, I guess, more efficient air conditioning means that less hot air is dumped into urban environment, which tends to create heat islands (and affects weather patterns).

Cooling down is catching on. As incomes rise and populations grow, especially in the world’s hotter regions, the use of air conditioners is becoming increasingly common. In fact, the use of air conditioners and electric fans already accounts for about a fifth of the total electricity in buildings around the world – or 10% of all global electricity consumption.Source: The Future of Cooling | IEAOver the next three decades, the use of ACs is set to soar, becoming one of the top drivers of global electricity demand. A new analysis by the International Energy Agency shows how new standards can help the world avoid facing such a “cold crunch” by helping improve efficiency while also staying cool.

Indigenous knowledge, sustainable design, and long-term thinking

This is a perfect example of the kind of sustainable design and long-term thinking we lose when we ignore indigenous knowledge.

In Western Australia, Marri trees, known as Gnaama Boorna in the Menang language, have been pruned by Aboriginal people for generations to collect and store rainwater. The ancient practice involves shaping the trees into a bowl-like structure, making them vital water sources in areas where water is scarce, and they are often found in ceremonial areas or high hills.

Source: Specially pruned for centuries in WA, marri trees provide a vital source of water for traditional owners | ABC NewsGnaama, meaning hole for water, and Boorna, meaning tree or timber.

[...]By pruning and trimming parts of specific trees as they grow, traditional owners encourage them to take on a unique, bowl-like shape — helping collect and store rain water.

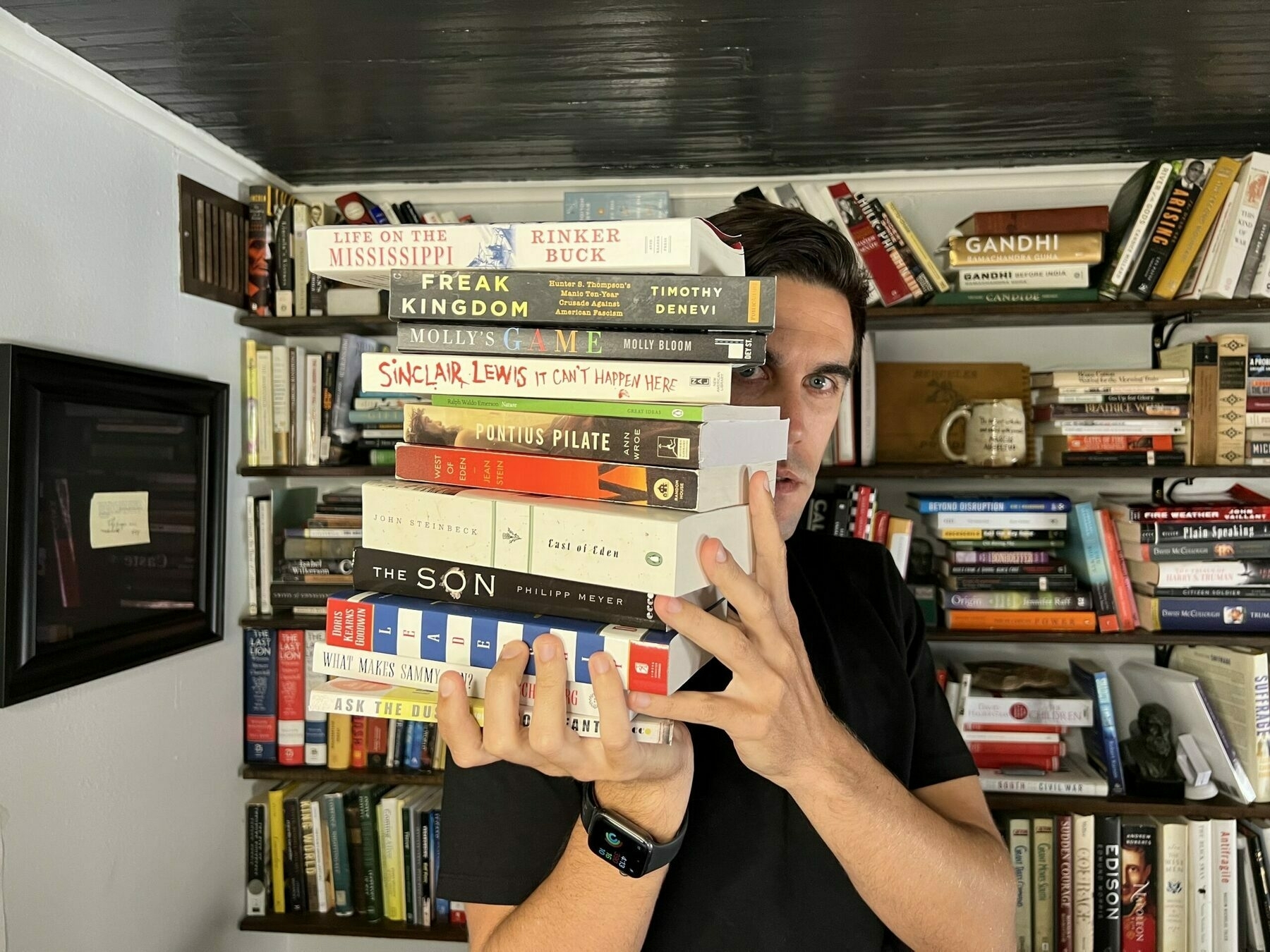

Some advice for readers

Less ‘rules’ than notes, this post by Ryan Holiday (himself a prolific author) is worth reading. I like the part where he turns the tables, “You say you don’t have time to read but what does the screen time app on your phone say? What does your calendar say?"

Along the way, Holiday emphasises the importance of a systematic approach over speed reading, advocates for physical books, note-taking, and seeking wisdom rather than mere facts. He also encourages readers to share impactful books with others. (You can check out my reading list and reviews here.)

So the question I am asked most often is:Source: These 38 Reading Rules Changed My Life | RyanHoliday.netHow do you read so much? What’s the secret?

The answer is not “I’m a speedreader.” As I’ve written before, speed reading is a scam. The answer is that I have a system, a process that helps me be a productive reader. It’s not my system exactly, as I’ve taken many strategies from history’s greatest readers. Nor is this a system designed around speed or quantity. Reading is wonderful in and of itself, why would I try to rush through it? No, I try to do it well. I try to enjoy it.

Generative AI, misinformation, and content authenticity

As a philosopher, historian, and educator by training, and a technologist by profession, this initiative really hits my sweet spot. The image below shows how, even before AI and digital technologies, altering the public record through manipulating photographs was possible.

Now, of course, spreading misinformation and disinformation is so much easier, especially on social networks. This series of posts from the Content Authenticity Initiative outlines ways in which the technology they are developing can be prove whether or not an image has been altered.

Of course, unless verification is built into social networks, this is only likely to be useful to journalists and in a court of law. After all, people tend to reshare whatever chimes with their worldview.

Although it varies in form and creation, generative AI content (a.k.a. deepfakes) refers to images, audio, or video that has been automatically synthesized by an AI-based system. Deepfakes are the latest in a long line of techniques used to manipulate reality — from Stalin's darkroom to Photoshop to classic computer-generated renderings. However, their introduction poses new opportunities and risks now that everyone has access to what was historically the purview of a small number of sophisticated organizations.Source: From the darkroom to generative AI | Content Authenticity InitiativeEven in these early days of the AI revolution, we are seeing stunning advances in generative AI. The technology can create a realistic photo from a simple text prompt, clone a person’s voice from a few minutes of an audio recording, and insert a person into a video to make them appear to be doing whatever the creator desires. We are also seeing real harms from this content in the form of non-consensual sexual imagery, small- to large-scale fraud, and disinformation campaigns.

Building on our earlier research in digital media forensics techniques, over the past few years my research group and I have turned our attention to this new breed of digital fakery. All our authentication techniques work in the absence of digital watermarks or signatures. Instead, they model the path of light through the entire image-creation process and quantify physical, geometric, and statistical regularities in images that are disrupted by the creation of a fake.

On the need to measure productivity

I’ve long said that no-one really knows what knowledge work looks like. It’s easy to see whether or not someone is digging a hole in the ground, but it’s much more difficult to see whether the work that someone is doing on a computer is ‘productive’.

This is, I think, partly because ‘productivity’ is something that is best thought about for things that can be systematised and made routine. A lot of knowledge work is fundamentally creative, and so quantitative metrics are meaningless. Who cares if you’ve made a million pull requests if they’re all to change a single character?

This article discusses the complexities of assessing productivity in various fields, the issues with current interviewing processes, and suggests that future evaluations may become more tied to tangible accomplishments rather than arbitrary metrics. That’s presupposing, of course, that hierarchical evaluations are even necessary.

[E]very potential metric we devise appears woefully inadequate in assessing this holistic outcome. Whether it's pull requests, lines of code, user stories, story points, or ship dates, it seems that every metric can be manipulated or gamed. Ship dates may be advanced, but quality suffers; story points morph in size depending on the project, and lines of code can be bulked up with a test suite. Even pull requests can be sliced and diced to skew the numbers. It's a frustrating conundrum.Source: Why is it so hard to measure productivity? | fractional.workFor more fuzzy fields, like product management or marketing or design, it becomes even more hand-wavey. Some fields tend to depend on getting other roles to execute better, but you can’t go rewind history and try things with a different PM to see if things would have been better. Same with design.

[…]

If you give the most productive employee more work, presumably they’d be justified in asking for higher compensation? After all, they are driving greater outcomes for you. Would you be comfortable paying it?

For example, would you pay a 3x more productive designer 3x the fully loaded cost of the average designer? If 10x engineers truly exist, why do pay scales intra company not cover a 10x spectrum?

[…]

My suspicion is that, like in other fields where performance matters and is financially rewarded, there will be a surge in our capacity to measure and evaluate real-life work performance. Compensation will become more closely tied to tangible accomplishments rather than arbitrary levels or seniority. Interviews will transition to be more real-world scenarios, perhaps within the customer’s actual codebase, addressing a genuine problem the customer faces—possibly even compensating the interviewee for their time.

Image: Kelly Sikkema

The declining relevance of Google search

I can’t remember the last time I searched Google. It’s been around six years since I used DuckDuckGo as my main search engine. Which is weird, because people use ‘google’ for searching the web as they do ‘hoover’ for vacuuming cleaning.

This article explores Google’s history and its impact on SEO, content creation. it’s written by Ryan Broderick, author of Garbage Day, a newsletter to which I subscribe. He charts the rise of alternative platforms like Meta’s Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, and suggests that Google’s era of influence may be waning.

There is a growing chorus of complaints that Google is not as accurate, as competent, as dedicated to search as it once was. The rise of massive closed algorithmic social networks like Meta’s Facebook and Instagram began eating the web in the 2010s. More recently, there’s been a shift to entertainment-based video feeds like TikTok — which is now being used as a primary search engine by a new generation of internet users.Source: How Google made the world go viral | The VergeFor two decades, Google Search was the largely invisible force that determined the ebb and flow of online content. Now, for the first time since Google’s launch, a world without it at the center actually seems possible. We’re clearly at the end of one era and at the threshold of another. But to understand where we’re headed, we have to look back at how it all started.

[…]

Twenty-five years ago, at the dawn of a different internet age, another search engine began to struggle with similar issues. It was considered the top of the heap, praised for its sophisticated technology, and then suddenly faced an existential threat. A young company created a new way of finding content.

Instead of trying to make its core product better, fixing the issues its users had, the company, instead, became more of a portal, weighted down by bloated services that worked less and less well. The company’s CEO admitted in 2002 that it “tried to become a portal too late in the game, and lost focus” and told Wired at the time that it was going to try and double back and focus on search again. But it never regained the lead.

That company was AltaVista.

An end to rabbit hole radicalization?

A new peer-reviewed study suggests that YouTube’s efforts to stop people being radicalized through its recommendation algorithm have been effective. The study monitored 1,181 people’s YouTube activity and found that only 6% watched extremist videos, with most of these deliberately subscribing to extremist channels.

Interestingly, though, the study cannot account for user behaviour prior to YouTube’s 2019 algorithm changes, which means we can only wonder about how influential the platform was in terms of radicalization up to and including pretty significant elections.

Around the time of the 2016 election, YouTube became known as a home to the rising alt-right and to massively popular conspiracy theorists. The Google-owned site had more than 1 billion users and was playing host to charismatic personalities who had developed intimate relationships with their audiences, potentially making it a powerful vector for political influence. At the time, Alex Jones’s channel, Infowars, had more than 2 million subscribers. And YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, which accounted for the majority of what people watched on the platform, looked to be pulling people deeper and deeper into dangerous delusions.Source: The World Will Never Know the Truth About YouTube’s Rabbit Holes | The AtlanticThe process of “falling down the rabbit hole” was memorably illustrated by personal accounts of people who had ended up on strange paths into the dark heart of the platform, where they were intrigued and then convinced by extremist rhetoric—an interest in critiques of feminism could lead to men’s rights and then white supremacy and then calls for violence. Most troubling is that a person who was not necessarily looking for extreme content could end up watching it because the algorithm noticed a whisper of something in their previous choices. It could exacerbate a person’s worst impulses and take them to a place they wouldn’t have chosen, but would have trouble getting out of.

[…]

The… research is… important, in part because it proposes a specific, technical definition of ‘rabbit hole’. The term has been used in different ways in common speech and even in academic research. Nyhan’s team defined a “rabbit hole event” as one in which a person follows a recommendation to get to a more extreme type of video than they were previously watching. They can’t have been subscribing to the channel they end up on, or to similarly extreme channels, before the recommendation pushed them. This mechanism wasn’t common in their findings at all. They saw it act on only 1 percent of participants, accounting for only 0.002 percent of all views of extremist-channel videos.

Nyhan was careful not to say that this paper represents a total exoneration of YouTube. The platform hasn’t stopped letting its subscription feature drive traffic to extremists. It also continues to allow users to publish extremist videos. And learning that only a tiny percentage of users stumble across extremist content isn’t the same as learning that no one does; a tiny percentage of a gargantuan user base still represents a large number of people.

Crypto is the biggest ponzi scheme of all time

Ben McKenzie, an actor turned anti-crypto activist, argues in his new book Easy Money that while cryptocurrencies highlight legitimate flaws in the financial system, they are essentially a Ponzi scheme.

He criticises the “Hollywoodisation” of crypto and the lack of regulatory oversight, warning that the tech utopianism surrounding crypto and now AI could leave many losers in its wake. It’s funny how people seamlessly move from one grift to the next without ever being properly called out on it.

The secret behind most conspiracy-driven movements is that there is often a glimmer of truth at the centre of their beliefs. Anti-vaxxers, for instance, can point to the past behaviour of large pharmaceutical companies as evidence that the medical establishment can’t be trusted. This glimmer is what’s used to ensnare you, says Ben McKenzie, the actor and cryptocurrency critic.Source: “The biggest Ponzi of all time”: why Ben McKenzie became a crypto critic | New Statesman[…]

After a friend urged him to buy Bitcoin, McKenzie – a former economics student with a degree from the University of Virginia – took a 24-part online course on cryptocurrencies, taught by the current US Securities and Exchange Commission chair Gary Gensler. He came away thinking the entire cryptocurrency thing was a scam. Worse, it was a scam with a lot of momentum behind it. “Advocates will tell you there is no ‘Bitcoin marketing department’,” McKenzie said. “But of course, if Bitcoin and crypto doesn’t have a product, if there is no actual tangible asset behind it, then in fact, Bitcoin and crypto is only marketing. It’s only a story.”

[…]

During the peak of 2021, some of the most recognisable people in the world – including Matt Damon, Reese Witherspoon and Kim Kardashian – began promoting cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

McKenzie told me this is part of a more aggressive “hustle culture” in which people use their social contacts to promote products. Multi-level marketing (or MLM) and pyramid-selling schemes have existed for at least a century, but they have been transformed by technology. “In the 1950s, if you wanted to sell someone Mary Kay Cosmetics or Tupperware, you would need to invite them over to your house, cook them dinner, spend three hours trying to convince them [to buy products].” Now, he said, “the MLM can be done through TikTok and Instagram.”

Though McKenzie is openly critical of the celebrities who have pushed these products, he reserves ultimate blame for the sluggish regulators that allowed it to happen. “I think in many cases the celebrities didn’t really understand what they were selling. Which is not to absolve them of a moral, ethical [or] potentially even legal responsibility for their actions. But they don’t need to be bad people – they just see easy money, right?”

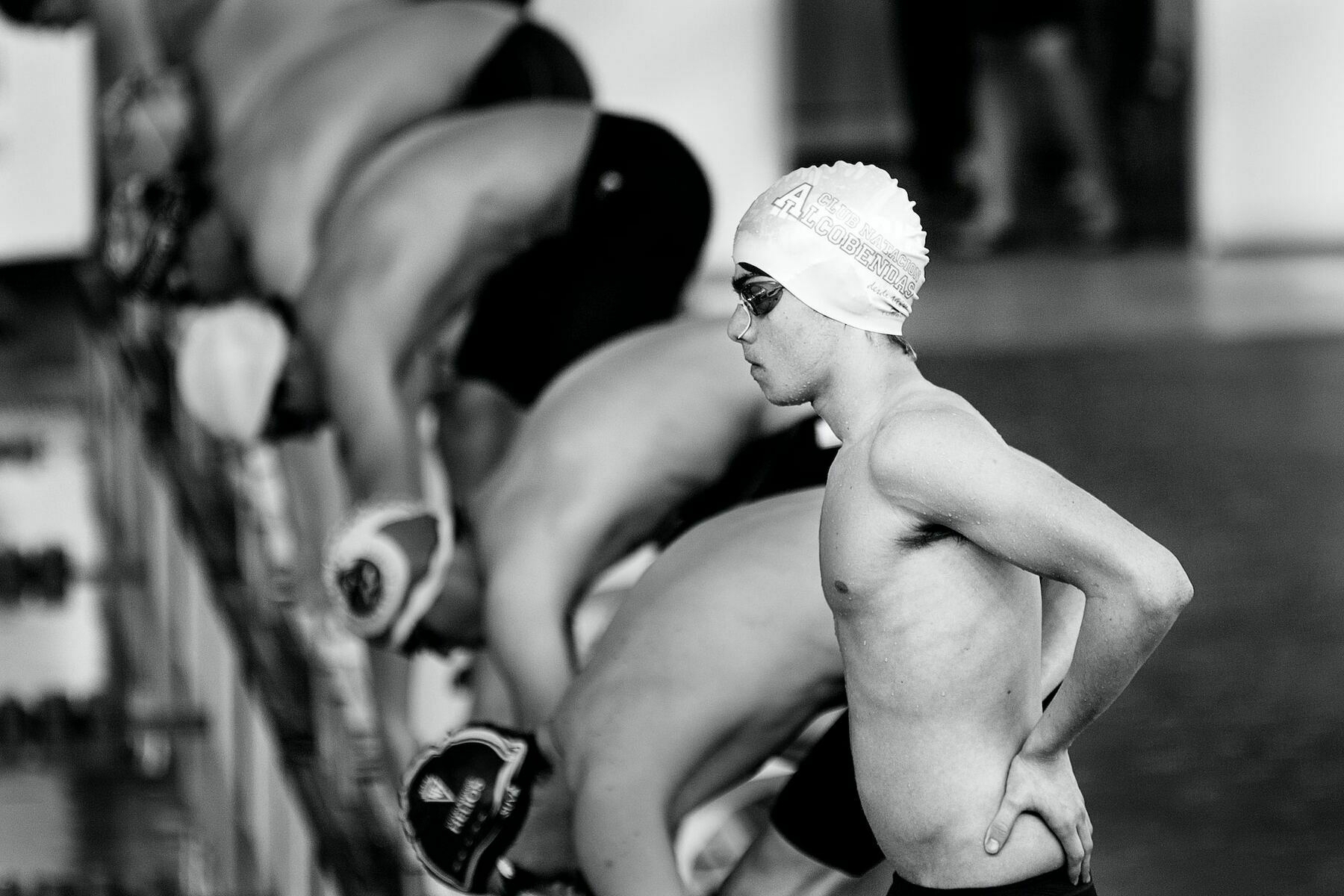

B Lane

There’s a lot going on in this short post. It reminded me of a saying of Steve Jobs: “A players attract A players. B players attract C players.”

Now there’s something in that, in terms of the mentality that people bring to working hard and playing hard. But this post is talking about the way that people treat other people.

I’ve definitely noticed in my life, from my own studies to my kids sports teams, the tyranny of the “not quite top-level” mindset. It’s almost like you have to get over yourself to get to the “top”. What that is and whether it’s worth pursuing is another question entirely.

I noticed that when I swam next to the B lane swimmers, they were not nearly as kind and friendly as the C lane swimmers had been when they were my next-lane neighbours. The A lane swimmers were extremely nice, and were generous with encouragement, praise and tips. This wasn’t a hard and fast rule, but I started to notice a pattern: A, C, and D lane swimmers tended to be nice, friendly, and helpful to pretty much everyone; B lane swimmers tended to be nice to A lane and other B lane swimmers but not so much to C and D.Source: The B Lane Swimmer | Holly WittemanWhen I stopped doing tris and moved back to field sports, I started to notice the same thing. The very top athletes were nice to everyone and so were the middle and bottom of the pack. The not quite top players, though, were less friendly. They played more political games, and acted out their threatened feelings of being not quite good enough by being snobbish to those below them. (In retrospect, I worry I did some of this, too, especially when I was playing on a top team but was not a top player. I definitely felt a need to prove myself.)

I have since noted the same phenomenon in nearly every domain, including academia. The truly great researchers are generous and friendly; so are many of the middle of the roaders. Those who have something to prove, though, and who feel like they aren’t quite managing to do it, show definite aspects of being B lane swimmers.

Image: Quino AI

Money does not solve disasters like this

The Burning Man Festival started in 1986 as a small event on a beach. It was originally an event for hippies, bohemians, and those who lived outside of mainstream culture. It’s an art event.

As with most things like this, it became cool, and so people with money started going. Now, less than 40 years later, it’s dominated by the Silicon Valley elite, celebrities, and grifters.

While one person has died this year due to extreme weather events, which is a tragedy, I can’t help but feel some schadenfreude at rich people being stuck in a situation they can’t buy their way out of.

Tens of thousands of “burners” at the Burning Man festival have been told to stay in the camps, conserve food and water and are being blocked from leaving Nevada’s Black Rock desert after a slow-moving rainstorm turned the event into a mud bath.Source: Burning Man festival-goers trapped in desert as rain turns site to mud | The Guardian[…]

As of noon Saturday, Nevada’s Bureau of Land Management declared the entrance to Burning Man shut down for good. “Rain over the last 24 hours has created a situation that required a full stop of vehicle movement on the playa. More rain is expected over the next few days and conditions are not expected to improve enough to allow vehicles to enter the playa,” read a BLM statement.

[…]

The festival this year was already taking place under unusual circumstances with the desert floor flooded by the remnants of Hurricane Hilary as the event was being set up.

Tara Saylor, an attendee from Ojai, California, faced the threat of the hurricane as well as a 5.1-magnitude earthquake that shook her city before she left, reported the Los Angeles Times. Saylor told the newspaper she’s seen the founders of two different companies at Burning Man this year, but added, “it doesn’t matter how much money you have, nobody can do anything about it. There’s no planes, there’s no buses.”

“Money does not solve disasters like this.”