On the importance of fluency in other people's love languages

I was talking to someone yesterday about ‘love languages’ which they hadn’t come across before. It’s easy to dismiss these kinds of things, but I’ve found this approach quite insightful when it comes to identifying people’s needs in relationships.

I’m not going to talk about other people’s love languages, but in my experience most people appreciate expressions of love (whether romantic or platonic) in two out of the five ways. For example, I’m all about words of affirmation (#1) and gifts (#3). That’s what I give out by default because that’s what I like to take in.

The reason the love languages approach is helpful is to realise that others might need something different to what you by default offer them. This particular article on the TED website is interesting because it was written during pandemic lockdowns and so gets creative with ways in which they can be expressed at distance.

What I find so helpful about love languages is that they express a basic truth. Implicit to the concept is a common-sense idea: We don’t feel or experience love in the same way. Some of us will only be content when we hear the words “I love you,” some prize quality time together, while some will feel most cared for when our partner scrubs the toilet.Source: Do you know the 5 love languages? Here’s what they are — and how to use them | TEDIn this way, love is a bit like a country’s currency: One coin or bill has great value in a particular country, less value in the countries that border it, and zero value in many other countries. In relationships, it’s essential to learn the emotional currency of the humans we hold dear and identifying their love language is part of it.

Love language #1: Words of affirmation

Those of us whose love language is words of affirmation prize verbal connection. They want to hear you say precisely what you appreciate or admire about them. For example: “I really loved it when you made dinner last night”; “Wow, it was so nice of you to organize that neighborhood bonfire”; or just “I love you.”[…]

Love language #2: Acts of service

Some of us feel most loved when others lend a helping hand or do something kind for us. A friend of mine is currently going through chemotherapy and radiation, putting her at high risk for COVID-19 and other infections. Knowing that her love language is acts of service, a group of neighbor friends snuck over under the cover of darkness in December and filled her flower pots in front of her house with holiday flowers and sprigs. Others have committed to shoveling her driveway all winter. (It’s Minnesota, so that’s big love.)[…]

Love language #3: Gifts

Those of us whose love language is gifts aren’t necessarily materialistic. Instead, their tanks are filled when someone presents them with a specific thing, tangible or intangible, that helps them feel special. Yes, truly, it’s the thought that counts.[…]

Love language #4: Quality time

Having another person’s undivided, dedicated attention is precious currency for the people whose love language is quality time. In a time of COVID-19 and quarantining, spending quality time together can seem challenging. But thanks to technology, it’s actually one of the easiest to engage in.[…]

Love language #5: Physical touch

Expressing the language of physical touch can be as platonic as giving a friend an enthusiastic fist-bump when she tells you about landing an interview for a dream job or as intimate as a kiss with your partner to mark the end of the workday.[…]

Love languages are a worthwhile concept to become fluent in during this pandemic time — and at this time in the world. Long before COVID arrived on the scene, we were already living through an epidemic of loneliness. Loneliness is not just about being alone; it’s about experiencing a lack of satisfying emotional connections. By taking the time to learn each other’s love languages and then using them, we can strengthen our relationships and our bonds to others.

Aristotle diagnoses our current political problems

The latest issue of New Philosopher magazine is about conflict. As usual, they quote a philosopher on the subject, in this case Aristotle in his Politics.

I studied Philosophy as an undergraduate and therefore read a lot of Aristotle. But it's been a couple of decades and I haven't gone back to him much inbetween. I tend to prefer the pre-Socratics.

Last week, I posted about Yuval Noah Harari talking about the post-truth revolutionary right. The quotation below from Aristotle is probably best read in that light: our current political situation in the west seems to spring from a combination of gaslighting and victim-blaming.

Now, in oligarchies the masses make revolution under the idea that they are unjustly treated, because, as I said before, they are equals, and have not an equal share, an in democracies the notables revolt, because they are not equals, and yet have only an equal share

Source: New Philosopher #41: Conflict

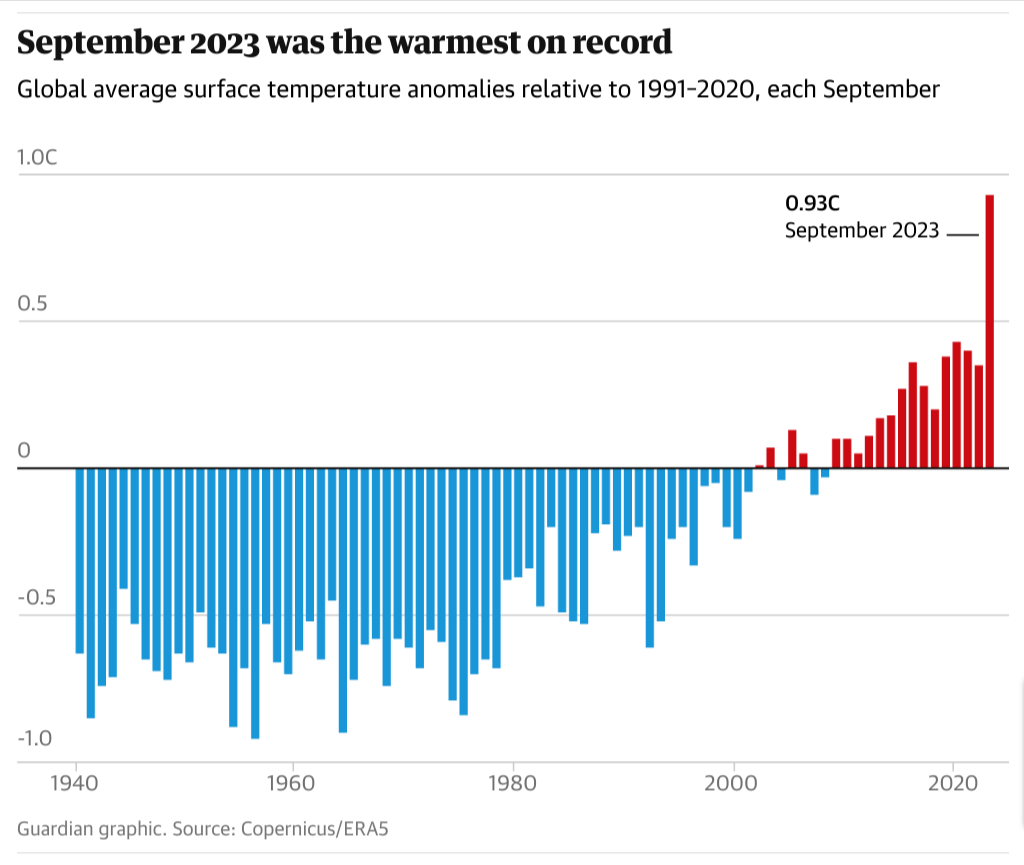

The rolling drama of the climate crisis just got a whole lot worse

It’s massively concerning that, although scientists seem to understand why the earth has been warming due to climate change over the last few decades, they don’t seem to know why there’s all of a sudden been a huge spike.

I just hope it’s not something like methane being released from permafrost, because then we are all completely shafted.

Global temperatures soared to a new record in September by a huge margin, stunning scientists and leading one to describe it as “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas”.Source: ‘Gobsmackingly bananas’: scientists stunned by planet’s record September heat | The GuardianThe hottest September on record follows the hottest August and hottest July, with the latter being the hottest month ever recorded. The high temperatures have driven heatwaves and wildfires across the world.

September 2023 beat the previous record for that month by 0.5C, the largest jump in temperature ever seen. September was about 1.8C warmer than pre-industrial levels. Datasets from European and Japanese scientists confirm the leap.

The heat is the result of the continuing high levels of carbon dioxide emissions combined with a rapid flip of the planet’s biggest natural climate phenomenon, El Niño. The previous three years saw La Niña conditions in the Pacific Ocean, which lowers global temperature by a few tenths of a degree as more heat is stored in the ocean.

[…]

The scientists said that the exceptional events of 2023 could be a normal year in just a decade, unless there is a dramatic increase in climate action. The researchers overwhelmingly pointed to one action as critical: slashing the burning of fossil fuels down to zero.

Five kinds of friends

Anyone who’s read Montaigne’s Essays will probably be slightly jealous of his friendship with Étienne de La Boétie. The latter tragically passed away at the age of 32, something that Montaine, it seemed, never fully got over. I’ve never had a friend like that. I doubt many men have.

This article from sociologist Randall Collins talks about five different types of friendship. I’ve got plenty of ‘allies’, some ‘backstage intimates’, and ‘mutual-interests friends’. I definitely lack, mainly out of choice ‘fun friends’ and ‘sociable acquaintances’.

It would be interesting to learn more about the history and sociology of friendship. This article goes a little bit into the realm of social media friends, but I’m not sure you can learn much about just studying the medium. That reminds me of a Douglas Adams quote I can’t quite find but goes something along the lines of people always talking about terrorists planning things “over the internet” but would never talk about them planning it “over a cup of tea”.

Allies: talking about money; asking for loans; asking for letters of reference, endorsements, asking to contact further network friends for jobs or investments. In specialized fields like scientific research, talking about what journals or editors to approach, what topics are hot, giving helpful advice on drafts. In art and music: gossiping about who’s doing what, contacts with agents, galleries, venues.Source: FIVE KINDS OF FRIENDS | The Sociological EyeBackstage intimates: Speaking in privacy; taking care not to be overheard. Don’t tell anybody about this.

Fun friends: Shared laughter, especially spontaneous and contagious. Facial and body indicators of genuine amusement, not forced smiles or saying “that’s funny” instead of laughing. Very strong body alignment, such as fans closely watching the same event and exploding in synch into cheers or curses.

Mutual-interests friends: talking at great length about a single topic. Being unable to tear oneself away from an activity, or from conversations about it.

Sociable acquaintances: General lack of all of the above, in situations where people expect to talk with each other about something besides practical matters (excuse me, can I get by?) Banal commonplace topics, the small change of social currency: the weather; where are you from; what do you do; foreign travels; do you know so-and-so? Answers to “how are you doing?” which avoid giving away information about one’s problems or matters of serious concern. Talking about politics can be conversational filler (when everyone assumes they’re in the same political faction), as often happens at the end of dinner parties when all other topics have been exhausted.

Image: Pixabay

Anxiety, deadness, and aggression

I can’t quite remember where I came across this article, but I’ve subscribed to the online magazine that it’s from, as it seems interesting.

The article itself explores, in quite a dense way, the psychological and societal aspects of labour, particularly in terms a capitalist framework. The author, Timofei Gerber, who is co-founder and co-editor of Epoché Magazine, argues that workers are alienated from the productive part of their labour. This leads to a cycle of dissatisfaction and unfulfilled potential.

Workers' alienation, he argues, is rooted in societal structures that prohibit the free flow of libidinal, or life-affirming, energy. Society therefore perpetuates a cycle of anxiety, deadness, and aggression, which further disconnects individuals from their creative and productive selves.

Well, I mean, it’s a theory. Reading this article felt a lot like reading Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, to be honest. A slog. 🥱

The desire of individuals to be productive, to be free and to be responsible for their lives, rejects all models of control, all hierarchy, all suppression. The individual that experiences pleasure, that is productive, is productive in all aspects of its life, it takes responsibility for its actions, and is therefore a very insubordinate subject. We have seen how our concept of labour is built on the model of hunger, and what consequences that has. The prohibition of pleasure has therefore but one function: to produce obedient subjects, which do not question the current order, and which do not desire to change the world. As the model of sexuality is rejected, the only accepted way towards satisfaction is based on the model of hunger: the constant need to fill the emptiness inside by succumbing to consumer society. It is for this reason that for Reich, the liberation of sexuality was of primary importance. It is true that people hunger and are suffering materially; but the reason for this does not originate from the sphere of hunger, it is not a physical necessity. Scarcity itself is artificially produced, an artificial hunger and emptiness that results from the blockage of the inherent productivity of life. And we accept this state of things because of our pleasure anxiety, because we are afraid of our own responsibility and freedom.Source: Wilhelm Reich on Pleasure and the Genesis of Anxiety | Epoché Magazine

Microcast #100 — Awkward Conversations

Instead of avoiding difficult conversations, aim to make them less awkward. Here's one way.

Show notes

Image: Unsplash

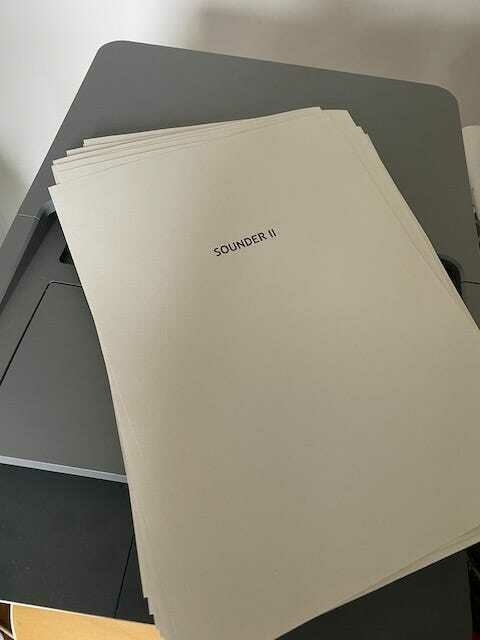

Different levels of reading (technologies)

This post by author Nick Harkaway was shared by Warren Ellis in his most recent newsletter. It’s something that my wife and I have talked about recently, as she tends to print everything out to read.

I do occasionally, but only for things I want to read really closely. In fact, I’ve got three levels: deep (paper), medium (e-ink), and shallow (screen). Most of the work that I do doesn’t require super-close reading of the text but rather the general gist of what’s going on. I’ve got an A4-sized ereader so it’s easy to put stuff on there.

Previously, I have printed out things. For example, I printed out my doctoral thesis and put it on the windows of the Jisc offices to make tiny corrections when I was almost ready for submission. I think this is entirely OK and normal.

What I really want is a laptop screen where I can switch between a regular screen and e-ink. Something like this.

There’s a sense of reality in printing (and reading on paper) a finished novel. In theory, you can go through an entire creative effort without ever producing paper on your desktop, but for me there’s a separate space of “tangible book” which has a particular moment and a set of uses. This morning I printed the first two chapters to look at, and aside from the sense of pleasure in seeing a physical manifestation of work done (in this instance a sort of echo, because I held the whole book in A4 recycled a while ago) there’s a difference between words on screen and words on paper.Source: The Print | FragmentaryHolding paper, I notice different things. The work feels different - different tonal issues arise, new sections I need to rewrite. It’s akin to - but different again from - reading a book aloud and hearing the cadences, the unintentional repetitions and homonyms, the blunt force wrongness of an unmodified word. The text is not different, but the experience is, and of course it’s still the paper experience of my book that most people will have. (I think - a couple of my books were bigger sellers as ebooks than paper in some markets, but as far as I know, perhaps even moreso now than a few years ago, paper remains on the throne.)

There are actual science reasons why analogue reading is different - and as the writing process at this point is founded on reading and re-reading, those aspects must be interwoven with the creative edit, irrespective of whether the creative process of itself works differently in the brain depending on the medium in which it is iterated. Whether it’s an inherent quality in the combination of tactile experience and inert text, or whether it’s contingent on my knowledge that digital text is both infinitely editable and subject to sudden interruption when my desktop decides to notify me of something, I find there’s a placidity and a sense of authenticity in the work. I’m always wary of mystifying the tree’s presence in the printed book or the long inheritance of paper, but - be it a societal form or something more fundamental - paper feels more “in the world”.

Perhaps switch to another search engine?

I use a lot of Google products. I’m typing this on a laptop on which I’ve installed ChromeOS Flex, I use Google Workspace at work, I’ve got a Google Assistant device in every room of our house, and now even my car has an infotainment system with it built in.

But I do take some precautions. I don’t use Google Search. I turn off my web history, watching history on YouTube, opt out of personalisation, and encrypt my Chrome browser sync with a password.

This article doesn’t surprise me, because Google’s core business is advertising. It’s still creepy though.

There have long been suspicions that the search giant manipulates ad prices, and now it’s clear that Google treats consumers with the same disdain. The “10 blue links,” or organic results, which Google has always claimed to be sacrosanct, are just another vector for Google greediness, camouflaged in the company’s kindergarten colors.Source: How Google Alters Search Queries to Get at Your Wallet | WIREDGoogle likely alters queries billions of times a day in trillions of different variations. Here’s how it works. Say you search for “children’s clothing.” Google converts it, without your knowledge, to a search for “NIKOLAI-brand kidswear,” making a behind-the-scenes substitution of your actual query with a different query that just happens to generate more money for the company, and will generate results you weren’t searching for at all. It’s not possible for you to opt out of the substitution. If you don’t get the results you want, and you try to refine your query, you are wasting your time. This is a twisted shopping mall you can’t escape.

Why would Google want to do this? First, the generated results to the latter query are more likely to be shopping-oriented, triggering your subsequent behavior much like the candy display at a grocery store’s checkout. Second, that latter query will automatically generate the keyword ads placed on the search engine results page by stores like TJ Maxx, which pay Google every time you click on them. In short, it’s a guaranteed way to line Google’s pockets.

Climate havens

I grew up in an ex-mining town, surrounded by ex-mining villages. At one point in my teenage years, I can distinctly remember wondering why people continued to live in such places once the reason for its existence had gone?

Now I’m an adult, of course I realise the many and varied economic, social, and emotional reasons. But still, the question remains: why do people live in places that don’t support a flourishing life?

One of the reasons that politicians are turning up the anti-immigration at the moment is because they’re well-aware of the stress that our planet is under. As this article points out, even if we reach net zero by 2050, the amount of carbon in the atmosphere means that some places are going to be uninhabitable.

That’s going to lead not only to international migration, but internal migration. We need to be preparing for that, not just logistically, but in terms of winning hearts and minds.

In 2022, climate change and climate-related disasters led nearly 33 million people to flee their homes and accounted for over half of all new numbers of people displaced within their countries, according to data from the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. This amount will surely increase over the next few decades.Source: The U.S. Government Should Push People To Move To Climate Havens | NoemaOutside the United States and Canada, the World Bank predicts that climate change will compel as many as 216 million people to move elsewhere in their countries by 2050; other reports suggest that more than one billion people will become refugees because of the impacts of a warming planet on developing countries, which may exacerbate or even precipitate civil wars and interstate armed conflict.

[…]

The extraordinary pressure that continued international and domestic climate migration will impose upon state resources and social goods like schools, hospitals and housing is difficult to fathom. Over the past year, city and state governments in the U.S. have feuded over the distribution of migrants stemming from the Southern border, with New York Mayor Eric Adams declaring that the current migration wave will “destroy” the city.

[…]

The stark fact is that the amount of carbon dioxide already amassed in the atmosphere all but assures that certain zones will become uninhabitable by the end of the century, regardless of whether global greenhouse gas emissions reach net zero by 2050. If factories cannot operate at full capacity due to life-threatening climate conditions, periodic grid failures and difficult-to-replace labor shortages over the next two decades — and these challenges reverberate throughout their surrounding economies — the output of the renewables sector will falter and stall projects to decarbonize businesses, government agencies and households.

In the long run, people can only treat you the way you let them

This blog post, which I discovered via Hacker News, is about ultimatums around ‘return to office’ mandates/ultimatums. But it’s also a primer to only allow people to treat you the way you want to be treated.

People who abuse any power they have over you aren’t worth respecting and definitely aren’t worth hanging around. Although sometimes it’s difficult to realise it, the chances are that you’re bringing the talent to the table, which is why they acting in a way fueled by insecurity.

If I had to give only one bit of advice to anyone ever faced with an ultimatum from someone with power over them (be it an employer or abusive romantic partner), it would be:Source: Return to Office Is Bullshit And Everyone Knows It | Dhole MomentsUltimately, never choose the one giving you an ultimatum.

If your employer tells you, “Move to an expensive city or resign,” your best move will be, in the end, to quit. Notice that I said, ‘in the end’.

It’s perfectly okay to pretend to comply to buy time while you line up a new gig somewhere else.

That’s what I did. Just don’t start selling your family home or looking at real estate listings, and definitely don’t accept any relocation assistance (since you’ll have to return it when you split).

Conversely, if you let these assholes exert their power over you, you dehumanize yourself in submission.

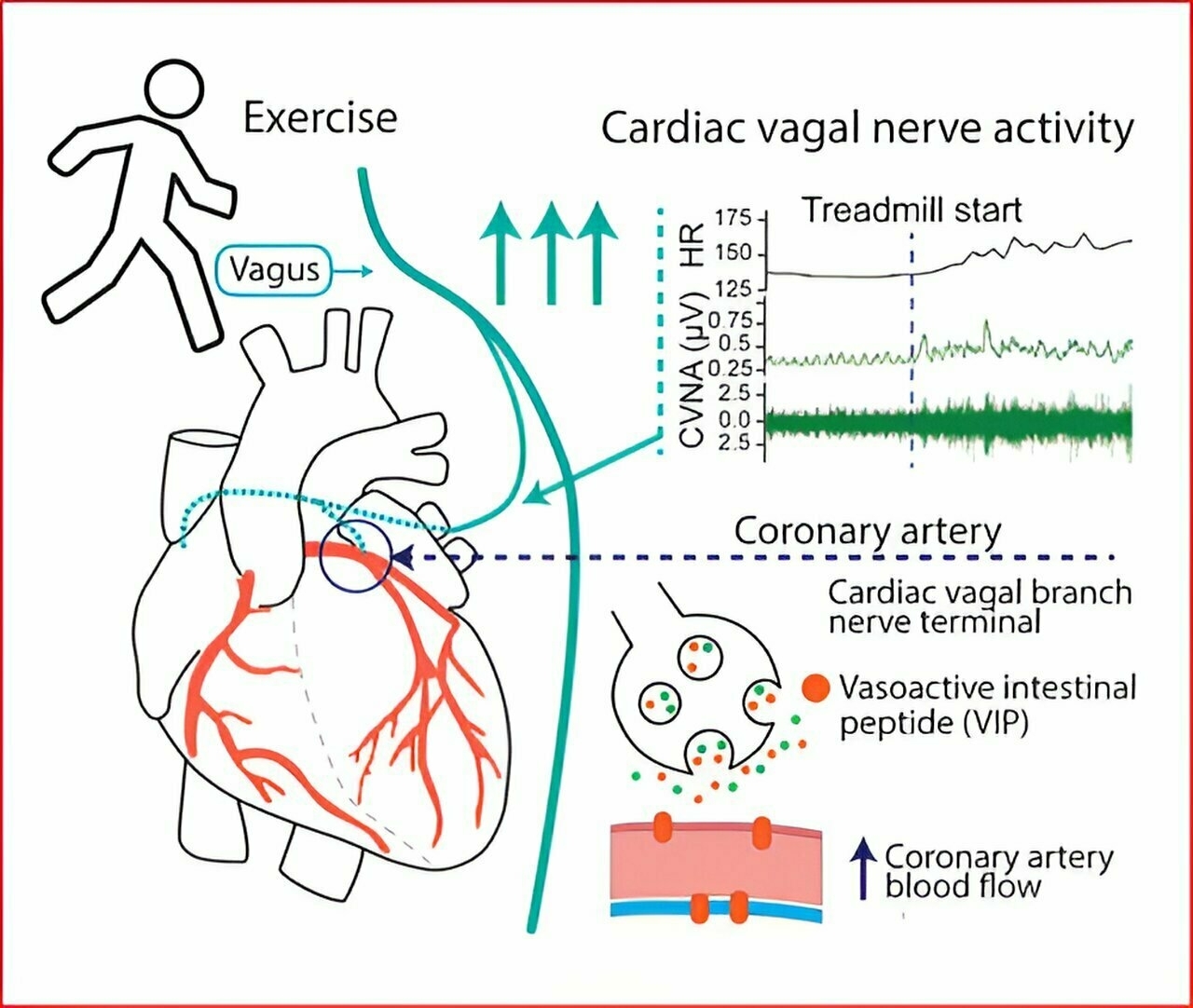

More on the vagus nerve (and exercise)

I mentioned a few weeks ago how researchers have been trying to electrically stimulate the vagus nerve, which is now thought to help treat everything from anxiety to depression.

In this study, researchers from the University of Auckland found that the vagus nerve, plays a significant role during exercise. Contrary to the prevailing understanding that only the ‘fight or flight’ nervous system is active during exercise, this study shows that activity in the vagus nerve actually increases. This helps the heart pump blood more effectively, supporting the body’s increased oxygen needs during exercise.

Interestingly, especially for people I know who have heart failure, they also identified that the vagus nerve releases a peptide which helps dilate coronary vessels. This allows more blood to flow through the heart.

The vagus nerve, known for its role in 'resting and digesting,' has now been found to have an important role in exercise, helping the heart pump blood, which delivers oxygen around the body.Source: Vagus nerve active during exercise, research finds | Medical XpressCurrently, exercise science holds that the ‘fight or flight’ (sympathetic) nervous system is active during exercise, helping the heart beat harder, and the ‘rest and digest’ (parasympathetic) nervous system is lowered or inactive.

However, University of Auckland physiology Associate Professor Rohit Ramchandra says that this current understanding is based on indirect estimates and a number of assumptions their new study has proven to be wrong. The work is published in the journal Circulation Research.

“Our study finds the activity in these ‘rest and digest’ vagal nerves actually increases during exercise,” Dr. Ramchandra says.

[…]

There is a lot of interest in trying to ‘hack’ or improve vagal tone as a means to reduce anxiety. Investigating this was outside the scope of the current study. Dr. Ramchandra says we do know that the vagus mediates the slowing down of heart rate and if we have high vagal activity, then our hearts should beat slower.

“Whether this is the same as relaxation, I am not sure, but we can say that regular exercise can improve vagal activity and has beneficial effects."

University is about more than jobs and earning power

Next month, I embark on my fourth postgraduate qualification: an MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice. I also believe that alternative credentials such as Open Badges are valuable. That’s because the answer to an ‘either/or’ question is usually ‘yes/and’.

So I have sympathy with this article which talks about potentially going too far in discouraging people from going to university. What’s missing from this piece, as usual with these things, is that Higher Education isn’t just about earning power. It’s about expanding your mind, worldview, and experiences.

I got involved with Open Badges 12 years ago because I wanted my kids to have the option of going to university, rather than it being table-stakes for a decent job. We’re not quite there yet, but we’re a lot closer than we used to be. It’s a delicate balance, because I don’t want a liberal education to be the preserve of a wealthy elite.

Wages grow faster for more-educated workers because college is a gateway to professional occupations, such as business and engineering, in which workers learn new skills, get promoted, and gain managerial experience. Most noncollege workers, in contrast, end up in personal services and blue-collar occupations, for which wages tend to stagnate over time.Source: The College Backlash Is Going Too Far | The Atlantic[…]

Despite the bad vibes around higher education, the fastest-growing occupations that do not require a college degree are mostly low-wage service jobs that offer little opportunity for advancement. Negative public sentiment might dissuade some people from going to college when it is in their long-run interest to do so. The potential harm is greatest for low- and middle-income students, for whom college costs are most salient. Wealthy families will continue to send their kids to four-year colleges, footing the bill and setting their children up for long-term success.

Indeed, highly educated elites in journalism, business, and academia are among those most likely to question the value of a four-year degree, even if their life choices don’t reflect that skepticism. In a recent New America poll, only 38 percent of respondents with household incomes greater than $100,000 said a bachelor’s degree was necessary for adults in the U.S to be financially secure. When asked about their own family members, however, that number jumped to 58 percent.

Image: Good Free Photos

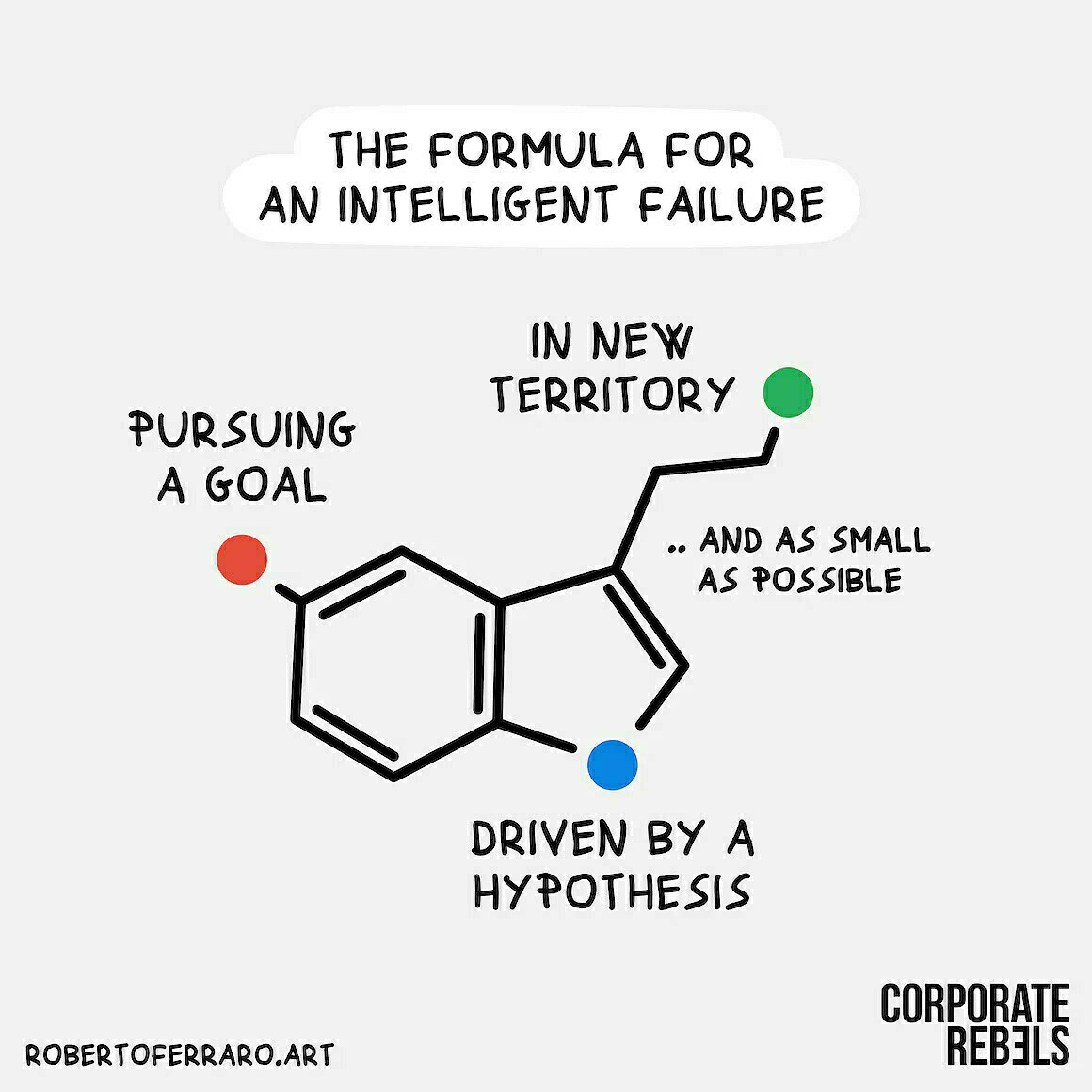

Intelligent failure

Andrew Curry links to Amy Edmondsen’s new book about ‘intelligent failure’. She’s also got a recorded talk from the RSA on the same topic which I’ve queued up to watch.

Although some people who have sat through teacher in-service training days may beg to differ, there’s no such thing as wasted learning. It’s all grist to the inspiration mill, and I’m always surprised at how often insights are generated between unexpected overlaps.

This, though, isn’t about serendipity, but rather about goal-directed behaviours to reach an outcome. Which pre-supposes, of course, that we’re working towards a goal. In these times of rolling catastrophe, it’s worth remembering that having goals is something that used to be normal.

We are all taught these days that failure is an essential part of learning, and that we need to fail if we want to develop as people. But it’s one thing to hear that, and another thing to be able to do it. Because we have all grown up in education systems where failure is bad, and worked for organisations where failure gets punished in a whole range of less-then-explicit ways.Source: Energy | Failing - by Andrew CurrySo it is interesting to see Amy Edmondsen writing about “intelligent failure” on the Corporate Rebels blog. She has just published a book on this theme.

[…]

The first part of this is to know that there are different kinds of failures. The set of things that are included in “intelligent failures” does not include failures that happened because you couldn’t be bothered. But it does include failures that happen as a result of complexity or bad luck.

So by working hard to prevent avoidable failures, they are able to embrace the other ones.

Edmondsen has developed a model from her research about intelligent failure which the Corporate Rebels turned into one of their distinctive graphics. Here are her four criteria:

It (1) takes place in new territory (2) in pursuit of a goal, (3) driven by a hypothesis, and (4) is as small as possible. Because they bring valuable new information that could not have gained in any other way, intelligent failures are praiseworthy indeed.

Falling asleep on the couch watching films

I can count on the fingers of no hands the number of times I’ve fallen asleep watching a film at home. I have, however, fallen asleep watching one at the cinema.

This is perhaps for three reasons. First, I usually wear contact lenses, but not when I’m in the cinema. Second, because my wife and I can’t seem to watch a film at home without pausing it half a dozen times. Third, because I’d rather read than watch a film.

So, yeah, this article isn’t for me. But I’m sharing it because I can’t really get into the mindset of someone for whom this is a problem.

I’ve watched the first half of a billion movies. This is how a typical movie night goes for me: After eating too many fries from Rocketbird and washing it down with a couple of beers, I’m swaddled in a plush blanket, horizontal on the couch, and zonked out long before Michelle Yeoh reaches the hotdog finger scene in Everything Everywhere All at Once.Source: How to Stop Falling Asleep on the Couch During Movies | WIREDMaybe your schedule is hectic, but you still want to catch every twist and turn in the Glass Onion movie. Or perhaps your significant other’s date-night selection seems like a snoozefest, and you’re attempting to roll credits on Morbius. Whatever your reason is to stay awake, keep the following advice in mind the next time you’re streaming something at home.

Yuval Noah Harari on the post-truth revolutionary right

Friend and collaborator Bryan Mathers recommended this episode of The Rest is Politics: Leading to me. While I’m a regular listener to the main podcast, which features only Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart, I hadn’t previously bothered with the ones where they interview others.

This one with Yuval Noah Harari is great. It’s the second part of a two-part interview. In the first, recorded in August, Harari talks about the situation in Israel. In this second one, he zooms out a bit to talk about politics more generally, AI, and society.

The thing that struck me, about 5-10 minutes in, was his point about the left and right of politics not making sense any more. That’s something that others have said before. But his analysis was fascinating: the right has largely abandoned the role of being guardians of tradition to weaponise ‘truth’, which has led to the left being in the awkward position of custodian. That’s why everything feels topsy-turvy.

(also, I’m really pleased to have discovered pod.link to share podcast episodes in a non-platform-specific way as easily as song.link)

(also also, I found out about a podcast search engine call Listen Notes recently!)

Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell, hosts of Britain's biggest podcast (The Rest Is Politics), have joined forces once again for their new interview podcast, ‘Leading’.Every Monday, Rory and Alastair interrogate, converse with, and interview some of the world's biggest names - from both inside and outside of politics - about life, leadership, or leading the way in their chosen field.Whether they're sports stars, thought-leaders, presidents or internationally-recognised religious figures, Alastair and Rory lift the lid on the motivation, philosophy and secrets behind their career.Tune in to 'Leading' now to hear essential conversation from some of the world's most enthralling individuals.Source: The Rest is Politics: Leading

Microcast #99 — EVs

Reflections on taking delivery of an electric vehicle (EV), including charging, business lease, and other rambling thoughts.

Show notes

Image: taken by me on my first run-out to Druridge Bay

Songs are not meme stocks

Remember NFTs? This article in The Guardian will help remind you of the heady days of early 2022 when digital images of monkeys were apparently extremely valuable. That article ends with a question: “what will the next NFT be? When will it drop? How much money will normal people end up spending on it?”

Here’s one answer: owning a slice of your favourite song. Or perhaps a popular song. Or an up-and-coming song. It’s essentially applying capitalism at the very smallest level possible, and treating cultural artifacts as commodities.

The article below in WIRED discusses a platform which offers this as a service. It’s a terrible idea on many levels, not least because, as we’ve seen recently, AI-generated music is tearing fandoms apart. I’ll sit this one out, thanks.

Imagine a retirement portfolio stocked with Rihanna hits, or a college fund fueled by Taylor Swift’s 1989. In a post-GameStop, post-NFT-mania world, it sounds plausible enough. Wholesome, even.Source: The Next Meme Stock? Owning a Slice of Your Favorite Song | WIREDA new music royalties marketplace, Jkbx (pronounced “jukebox”), launched this month and plans to officially open for trading later this year. It has filed an application with the US Securities and Exchange Commission and is waiting for notice that the SEC has qualified its offerings. As long as that goes according to plan, Jkbx—god, why no vowels?—will allow fans to buy “royalty shares,” or fractionalized portions of royalties, fees, and other income associated with a particular song. Prices are within reach of regular people. One share of composition royalties for Beyoncé’s “Halo,” for example, is $28.61. You could also buy a slice of the song’s sound recording royalties for the same price.

[…]

Jkbx is debuting with some big-name slices, and is led by a guy with a good track record. “They are very sophisticated,” Round Hill Music founder and CEO Josh Gruss says. “The real deal.” Others agree. “We think they are going to be successful,” Hipgnosis Songs CEO and founder Merck Mercuriadis says.

Still, plenty of industry analysts and insiders view Jkbx, and the larger world of royalty trading, warily. “I think there are going to be very modest levels of return,” says Serona Elton, a music industry professor at the University of Miami.

“There is skepticism about how good of an alternative investment strategy something like this is,” musician and data analyst Chris Dalla Riva says.

“I don’t understand why people keep trying to spin this idea up,” adds producer and music tech researcher Yung Spielburg. “I just don’t get it.”

Adversarial interoperability to return to a world of 'fast companies'

Cory Doctorow is one of my favourite people on the entire planet. I’ve heard him speak in person and online on numerous occasions. I met him a couple of times while at Mozilla, and he’s even recommended swimming pools in Toronto to me when I visited. (He’s a daily swimmer due to chronic back pain.)

His new book, which I’m saving to read for my next holiday, is The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of Computation. In this interview as part of promoting the book, he talks about how we’ve ended up in a world without real competition in the technology marketplace. Essential reading, as ever.

There used to be a time when the tech sector could be described as a bunch of “fast companies,” right? They would use the interoperability that’s latent in all digital technology and they would specifically target whatever pain points the incumbent had introduced. If incumbents were making money by showing you ads, they made an ad blocker. If incumbents were making money by charging gigantic margins on hard drives, they made cheaper hard drives.Source: Cory Doctorow: Silicon Valley is now a world of ‘lumbering behemoths’ | Fast CompanyOver time, we went from an internet where tech companies more or less had their users’ backs, to an internet where tech companies are colluding to take as big a bite as possible out of those users. We do not have fast companies anymore; we have lumbering behemoths. If you’ve started a fast company, it’s probably just a fake startup that you’re hoping to get acqui-hired by one of the big giants, which is something that used to be illegal.

As these companies grew more concentrated, they were able to collude and convince courts and regulators and lawmakers that it was time to get rid of the kind of interoperability, the reverse engineering that had been a feature of technology since the very beginning, and move into a new era in which no one was allowed to do anything to a tech platform that their shareholders wouldn’t appreciate. And that the government should step in to use the state’s courts to punish anyone who disagrees. That’s how we got to the world that we’re in today.

Sycamore Stump

There is, or rather was, a tree that symbolised the North East of England. Standing at a dip in the ground along Hadrian’s Wall called ‘Sycamore Gap’, it’s a tree I’ve visited many times with friends and family. Last year, when I walked the wall in 72 hours, it was a familiar touchstone.

Now the iconic 200 year-old tree, which featured in the film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, is gone. Felled by a 16 year-old in an act of wanton vandalism. On a World Heritage Site. Some people just want to watch the world burn.

It didn’t take long for someone to rename the place on Google Maps where the tree used to stand to ‘Sycamore Stump’. Hopefully they will build some kind of memorial to it. I do think it’s difficult for someone not from the region to understand just how important things like this are to one’s identity.

A 16-year-old boy has been arrested in northern England in connection with what authorities described as the “deliberate” felling of a famous tree that had stood for nearly 200 years next to the Roman landmark Hadrian’s Wall.Source: ‘Incredibly sad day’: Teen arrested in England after felling ancient tree | Al Jazeera[…]

Photographs from the scene on Thursday showed the tree was cut down near the base of its trunk, with the rest of it lying on its side.

Northumbria Police said the teen was arrested on suspicion of causing criminal damage. He was in police custody and assisting officers with their inquiries.

[…]

“This is an incredibly sad day,” police Superintendent Kevin Waring said. “The tree was iconic to the North East and enjoyed by so many who live in or who have visited this region.”

Image: Oli Scarff / Agence France-Presse (taken from NYT article)

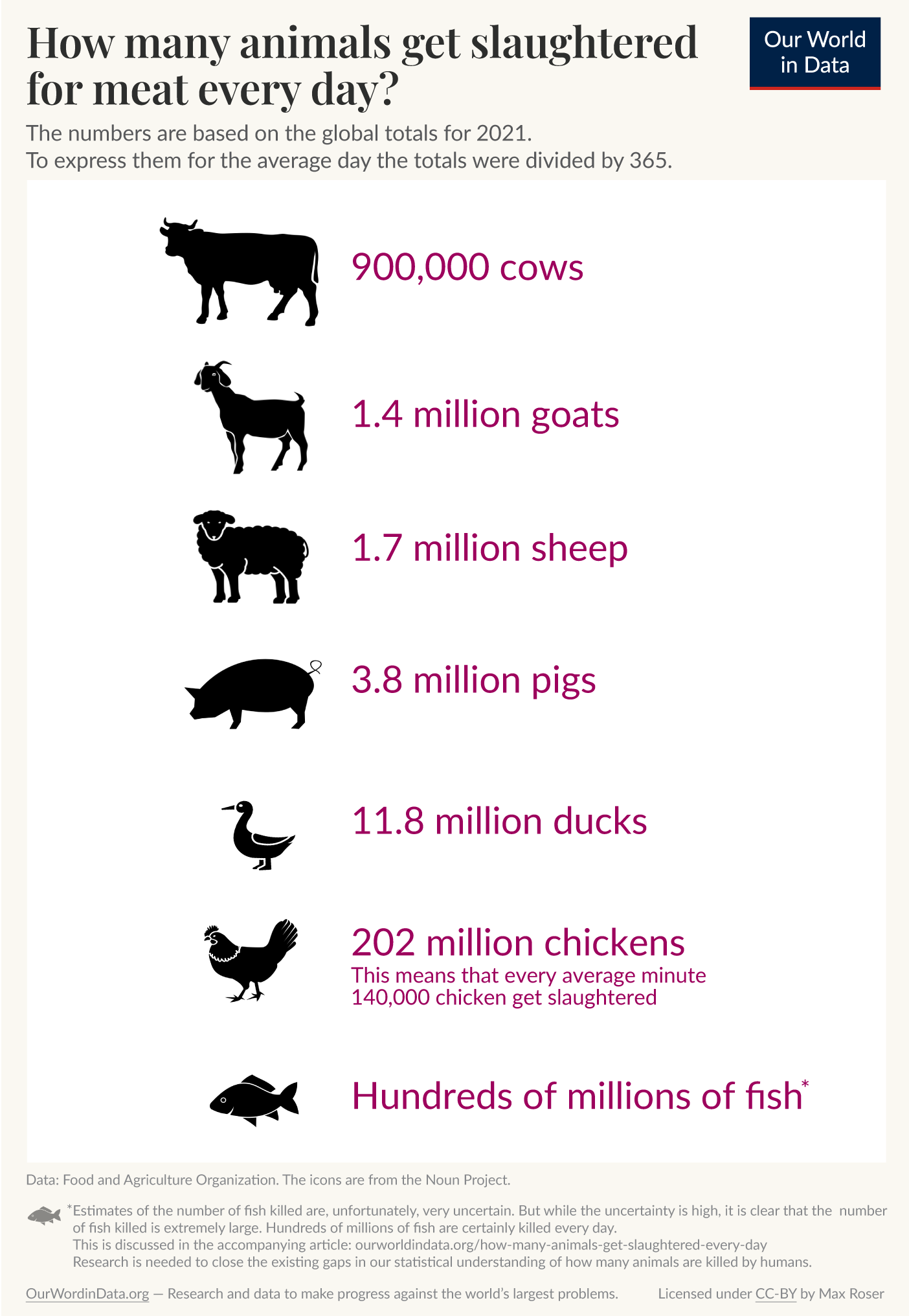

Please consider stopping eating animals

I don’t know how many people reading this are vegans or vegetarians. I was a pescetarian from October 2017 to January 2020 and then, since then, stopped eating fish too.

The reason I stopped eating meat was because of an article about the number of chickens that are killed each day. You can say that the actual death is painless, but they’re reared to have terrible lives, and many of them are electrocuted to death because it’s the cheapest method.

I’m sorry if this is shocking to you, but it’s even more shocking to the chickens. Eating meat is bad for your long-term health, bad for the environment, and ethically dubious. I’m not particularly interested if you agree right now, but I’d like you consider whether you’re on the right side of history.

My plan is to eventually turn vegan. I’ve replaced most of my milk consumption, including in tea and coffee, with oat milk.

The scale of humanity’s meat consumption is enormous. 360 million tonnes of meat every year.Source: How many animals get slaughtered every day? | Our World in DataThis number is so large that I find it impossible to comprehend. What helps me to make these numbers more relatable is to turn them from the weight of meat to the number of animals and from the yearly total to the daily number. This is what I have done in the graphic below. It shows how many animals are slaughtered on any average day.

About 900,000 cows are slaughtered every day. If every cow was 2 meters long, and they all walked right behind each other, this line of cows would stretch for 1800 kilometers. This represents the number of cows slaughtered

For chickens, the daily count is extremely large – 202 million chickens every day. To comprehend the scale, it is better to bring it down to the average minute: 140,000 chickens are slaughtered every minute.

The number of fish killed every day is very uncertain. I discuss this in some detail at the end of this article. But while the uncertainties are large, it is clear that the number of fish killed is large: certainly, hundreds of millions of fish are killed every day.If you believe that the slaughter of animals causes them to suffer and attribute even a small measure of ethical significance to their suffering, then the moral scale of this reality is immense.