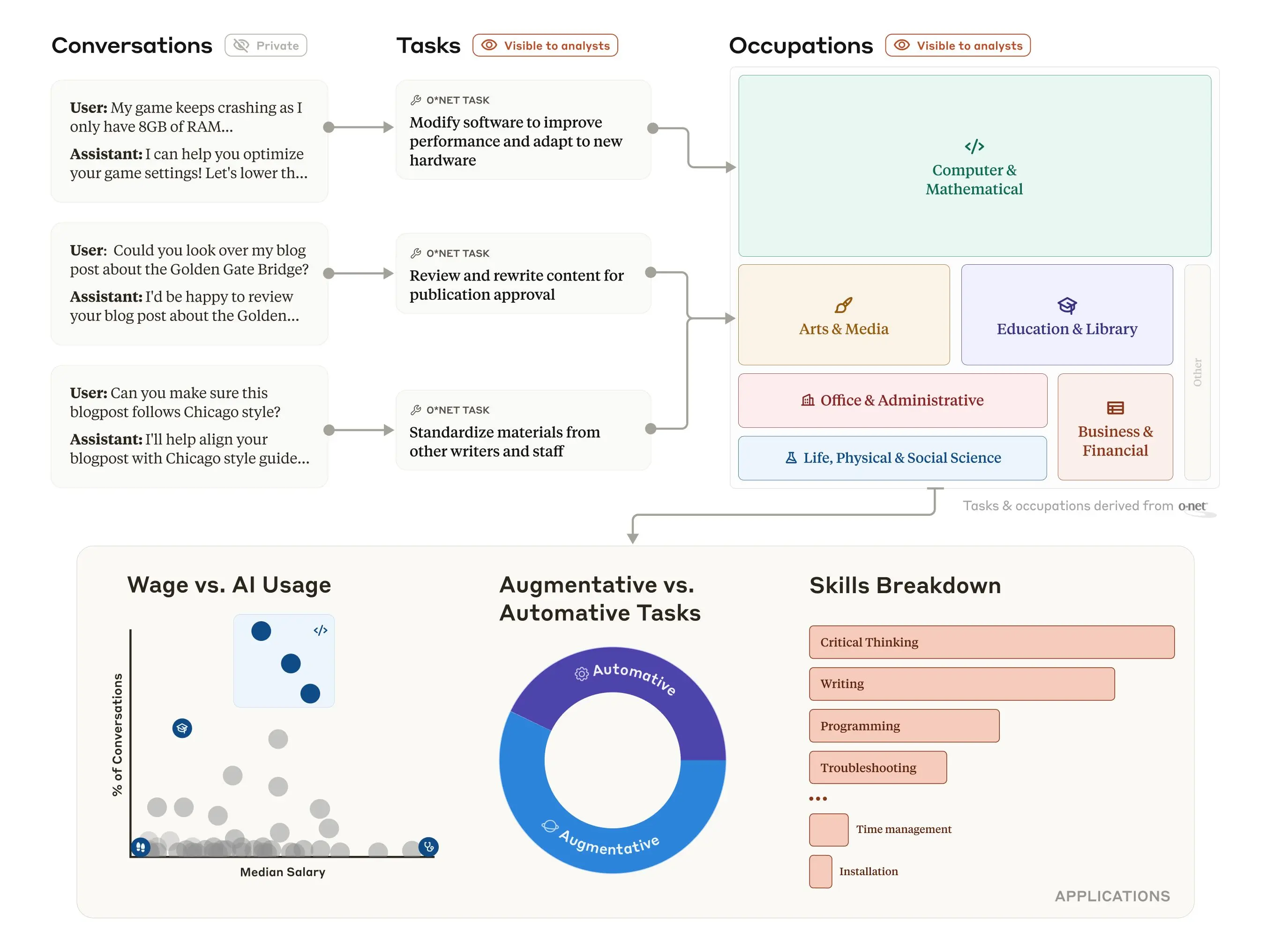

The occupational classification of a conversation does not necessarily mean the user was a professional in that field

I find this report (PDF) by Anthropic, the AI company behind Claude.ai, really interesting. First, I have to note that they’ve purposely used a report style that looks like it’s been published in an academic journal. But, of course, it hasn’t, which means it’s not peer-reviewed. I’m not saying this invalidates the findings in anyway, especially as they’ve open-sourced the dataset used for the analysis.

Second, although they’ve mapped occupational categories, as the Anthropic researchers point out, “the occupational classification of a conversation does not necessarily mean the user was a professional in that field.” I’ve asked LLMs about health-related things, for example, but I am not a health professional.

Third, and maybe I’m an edge case here, but I use different LLMs for different purposes:

- I primarily use ChatGPT for writing and brainstorming assistance, as well as converting one thing into another. For example, this morning I fed it some PDFs to extract skills frameworks as JSON.

- I use Perplexity when searching for stuff that might take a while to find — for example, the solution a technical problem that might be on an obscure Reddit or Stack Exchange thread.

- I turn to Google’s Gemini if I want to have a conversation with an LLM, say if I’m preparing for a presentation or an interview.

- I use Claude for code-related things because it can create interactive artefacts which can be useful.

- Finally, for sensitive work, or if a client specifically asks, I use Recurse.chat to interact with local LLM models such as LLaVA and Llama.

What I’m saying, I suppose, is that there’s an element of horses for courses with all of this. Increasingly, people will use different kinds of LLMs, sometimes without even realising it. If Anthropic looked at my use of Claude, they’d probably think I had some kind of programming or data analysis job. Which I don’t. So let’s take this with a grain of salt.

The following extract is taken from the report:

Here, we present a novel empirical framework for measuring AI usage across different tasks in the economy, drawing on privacy-preserving analysis of millions of real-world conversations on Claude.ai [Tamkin et al., 2024]. By mapping these conversations to occupational categories in the U.S. Department of Labor’s O*NET Database, we can identify not just current usage patterns, but also early indicators of which parts of the economy may be most affected as these technologies continue to advance.

We use this framework to make five key contributions:

1. Provide the first large-scale empirical measurement of which tasks are seeing AI use across the economy …Our analysis reveals highest use for tasks in software engineering roles (e.g., software engineers, data scientists, bioinformatics technicians), professions requiring substantial writing capabilities (e.g., technical writers, copywriters, archivists), and analytical roles (e.g., data scientists). Conversely, tasks in occupations involving physical manipulation of the environment (e.g., anesthesiologists, construction workers) currently show minimal use.

2. Quantify the depth of AI use within occupations …Only ∼ 4% of occupations exhibit AI usage for at least 75% of their tasks, suggesting the potential for deep task-level use in some roles. More broadly, ∼ 36% of occupations show usage in at least 25% of their tasks, indicating that AI has already begun to diffuse into task portfolios across a substantial portion of the workforce.

3. Measure which occupational skills are most represented in human-AI conversations ….Cognitive skills like Reading Comprehension, Writing, and Critical Thinking show high presence, while physical skills (e.g., Installation, Equipment Maintenance) and managerial skills (e.g., Negotiation) show minimal presence—reflecting clear patterns of human complementarity with current AI capabilities.

4. Analyze how wage and barrier to entry correlates with AI usage …We find that AI use peaks in the upper quartile of wages but drops off at both extremes of the wage spectrum. Most high-usage occupations clustered in the upper quartile correspond predominantly to software industry positions, while both very high-wage occupations (e.g., physicians) and low-wage positions (e.g., restaurant workers) demonstrate relatively low usage. This pattern likely reflects either limitations in current AI capabilities, the inherent physical manipulation requirements of these roles, or both. Similar patterns emerge for barriers to entry, with peak usage in occupations requiring considerable preparation (e.g., bachelor’s degree) rather than minimal or extensive training.

5. Assess whether people use Claude to automate or augment tasks …We find that 57% of interactions show augmentative patterns (e.g., back-and-forth iteration on a task) while 43% demonstrate automation-focused usage (e.g., performing the task directly). While this ratio varies across occupations, most occupations exhibited a mix of automation and augmentation across tasks, suggesting AI serves as both an efficiency tool and collaborative partner.

Source: The Anthropic Economic Index

Image: (taken from the report)

Flash fictions and creative constraints

In his most recent newsletter, Warren Ellis shares his belief that the ideal length of an email is “10 to 75 words.” He compares this with telegrams and postcards, using these as a creative constraint for what he calls ‘flash fictions’.

The average number of words on a postcard was between forty and fifty. The average number of words in a telegram was around fourteen. Last year, I started playing with flash fictions again for the first time in more than a decade. Here’s some.

[…]

The first ever time someone takes your hand, and the first thought you have is “this is everything” and the second is “what happens when it’s gone?” The space of time between those thoughts defines the shape of your life.

[…]

Flat gray post-funeral day, feeling like a human shovel as you dig into your mother’s hoarded life-debris. At the bottom of the midden of corner-shop crap, the book of her crimes. And you recognise your father’s chest tattoo covering its scabbed boards.

[…]

That point at the end of winter when your bones feel damp.

[…]

From my perspective, houses are roomy coffins with plumbing.

Source: Orbital Operations

Image: Jenny Scott

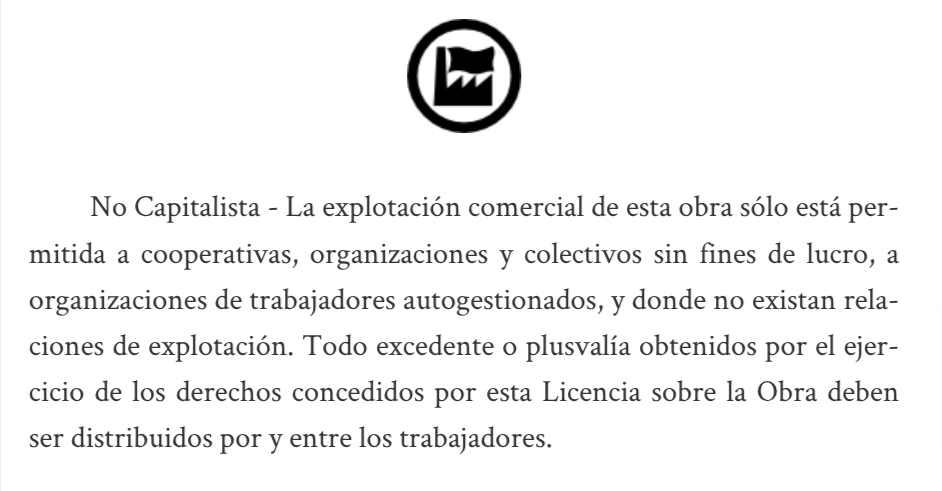

Surplus value must be distributed by and among the workers

I’ve come across lots of different licenses in my time. Some, such as Creative Commons licenses, for example, are meant to stand up in court. Others are more of a form of artistic expression, a way of signalling to an in-group, and a ‘hands-off’ warning for those therefore considered ‘out-group’.

My Spanish is still terrible, so I used DeepL to make the translation of this ‘Non-Capitalist’ clause on the En Defensa del Software Libre website, which is used in addition to the standard Attribution and Share-Alike clauses.

Non-Capitalist - Commercial exploitation of this work is only permitted to cooperatives, non-profit organisations and collectives, self-managed workers' organisations, and where no exploitative relationships exist. Any surplus or surplus value obtained from the exercise of the rights granted by this Licence on the Work must be distributed by and among the workers.

Original Spanish:

No Capitalista - La explotación comercial de esta obra sólo está permitida a cooperativas, organizaciones y colectivos sin fines de lucro, a organizaciones de trabajadores autogestionados, y donde no existan relaciones de explotación. Todo excedente o plusvalía obtenidos por el ejercicio de los derechos concedidos por esta Licencia sobre la Obra deben ser distribuidos por y entre los trabajadores.

Source: En Defensa del Software Libre

The art of not being governed like that and at that cost

I haven’t yet listened to the episode of Neil Selwyn’s podcast entitled ‘What is ‘critical’ in critical studies of edtech? but I couldn’t resist reading the editorial written by Felicitas Macgilchrist in the open-access journal Learning, Technology and Society.

Macgilchrist argues that we shouldn’t take the word ‘critical’ for granted, and outlines three ways in which it can be considered. I particularly like her approach to critique of moving the conversation forward by “raising questions and troubling… previously held assumptions and convictions.”

Given what’s happening in the US at the moment, I’ve pulled out the Foucault quotation as making it difficult to be governed is absolutely how to resist authoritarianism — in any area of life.

When Latour (2004) wondered if critique had ‘run out of steam’, this led to a flurry of responses about critical scholarship today. If, he wrote, his neighbours now thoroughly debunk ‘facts’ as constructed, positioned and political, then what is his role as a critical scholar? Latour proposes in response that ‘the critic is not the one who debunks, but the one who assembles’ (2004, 246). And, in this sense, ‘assembling’ joined proposals to see critical scholarship as ‘reparative’, rather than paranoid or suspicious (Sedgwick 1997), as ‘diffraction’, creating difference patterns that make a difference (Haraway 1997, 268) or as ‘worlding’, a post-colonial critical practice of creation (Wilson 2007, 210). These generative approaches have been picked up in research on learning, media and technology, for instance, analysing open knowledge practices (Stewart 2015) or equitable data practices (Macgilchrist 2019), and most explicitly in feminist perspectives on edtech (Eynon 2018; Henry, Oliver, and Winters 2019). […]

Generative forms of critique invite us to imagine other futures, and have inspired a range of speculative work on possible futures. Futurity becomes, in these studies, less about predicting the future or joining accelerationist or transhumanist futurisms, but about estranging readers from common-sense. SF ‘isn’t about the future’ (Le Guin [1976] 2019, xxi), it’s about the present, generating ‘a shocked renewal of our vision such that once again, and as though for the first time, we are able to perceive [our contemporary cultures’ and institutions’] historicity and their arbitrariness’ (Jameson 2005, 255). […]

If critique is not fault-finding or suspicion but, as one often cited source has it, the ‘art of not being governed like that and at that cost’ (Foucault 1997, 29; Butler 2001), then the critical work outlined here aims to identify how we are currently being governed, to question how this produces the acceptable or desirable horizons of ‘good education’, ‘good teaching’ or ‘good citizens’, and to speculate on alternatives.

Source: Learning, Media and Technology

Image: Marija Zaric

⭐ Become a Thought Shrapnel supporter!

Just a quick reminder that you can become a supporter of Thought Shrapnel by clicking here. Thank you to The Other Doug and ARTiFactor for their one-off tips last week!

We're all below the AI line except for a very very very small group of wealthy white men

As a fully paid-up member of the Audrey Watters fan club, I make no apologies for including another one of her articles in Thought Shrapnel this week. This one has much that I could dwell on, but I’m trying not to post too much about the current digital overthrow of democracy in the US at the moment.

One could also say that I could stop posting as much about AI, but then that’s all my information feeds are full of at the moment. And, anyway, it’s an interesting topic.

While you should absolutely go and read the full text, I pulled the following out of Audrey’s post, which references something that I’ve also referenced Venkatesh Rao discuss: being above or below the “API line”. These days, it’s more like an “AI line”

In 2015, an essay made the rounds (in my household at least) that argued that jobs could be classified as above or below the “API line” – above the API, you wield control, programmatically; below, however, your job is under threat of automation, your livelihood increasingly precarious. Today, a decade later, I think we’d frame this line as an “AI” not an “API line” (much to Kin’s chagrin). We’re all told – and not just programmers – that we have to cede control to AI (to “agents” and “chatbots”) in order to have any chance to stay above it. The promise isn’t that our work will be less precarious, of course; there’s been no substantive, structural shift in power, and if anything, precarity has gotten worse. AI usage is merely a psychological cushion – we’ll feel better if we can feel faster and more efficient; we’ll feel better if we can think less.

We’re all below the AI line except for a very very very small group of wealthy white men. And they truly fucking hate us.

It’s a line, it’s always a line with them: those above, and those below. “AI is an excuse that allows those with power to operate at a distance from those whom their power touches,” writes Eryk Salvaggio in “A Fork in the Road.” Intelligence, artificial or otherwise, has always been a technology of ranking and sorting and discriminating. It has always been a technology of eugenics.

Source: Second Breakfast

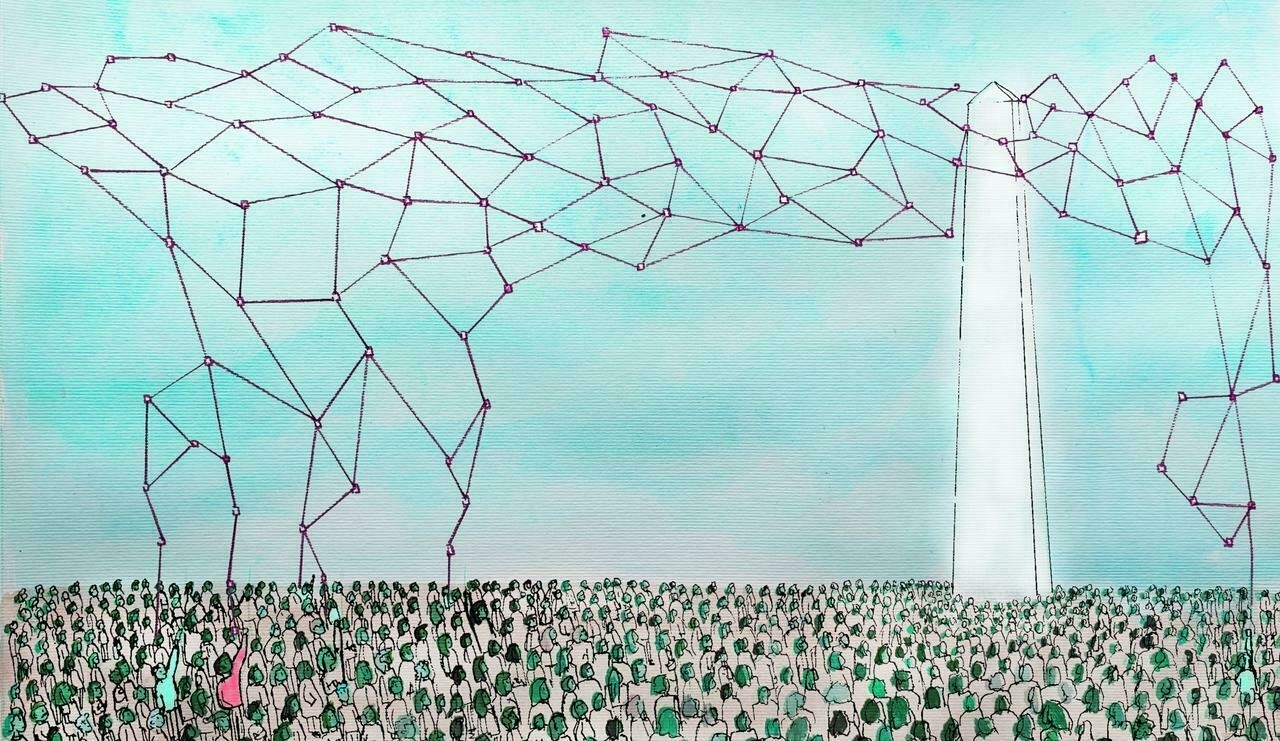

Image: CC-BY Jamillah Knowles & We and AI / Better Images of AI / People and Ivory Tower AI

Philosophically discontinuous times?

You should, as they say, “follow the money” when people make pronouncements. And when they’re confusing, grand-sounding, and vague, full of big words that point to a radically different future, I’d argue that you should be wary. I’ve re-read this interview with Tobias Rees several times, and I’ve concluded that what he’s saying is… bollocks.

Rees is a “founder of… an R&D studio located at the intersection of philosophy, art and technology” while also being “a senior fellow of Schmidt Sciences’ AI2050 initiative and a senior visiting fellow at Google.” Oh, and he’s a former editor of NOEMA, where this interview is published. While some of what he says sounds relatively believable, I just can’t get over this statement:

What makes AI such a profound philosophical event is that it defies many of the most fundamental, most taken-for-granted concepts — or philosophies — that have defined the modern period and that most humans still mostly live by. It literally renders them insufficient, thereby marking a deep caesura.

The idea that AI is a “profound philosophical event” should start your eyes rolling, and I’d be surprised if they haven’t rolled out of your head by the time you finish the next bit:

The human-machine distinction provided modern humans with a scaffold for how to understand themselves and the world around them. The philosophical significance of AIs — of built, technical systems that are intelligent — is that they break this scaffold.

That that means is that an epoch that was stable for almost 400 years comes — or appears to come — to an end.

Poetically put, it is a bit as if AI releases ourselves and the world from the understanding of ourselves and the world we had. It leaves us in the open.

In general, when people start arbitrarily dividing history into epochs (think “second industrial revolution,” etc.) they usually don’t know what they’re talking about. Rees manages to mention a bunch of philosophers (Karl Jaspers, Karl Marx, Martin Heidegger, etc.) but it’s a scatter-gun approach. Again, I don’t really think he knows what he’s talking about:

The alternative to being against AI is to enter AI and try to show what it could be. We need more in-between people. If my suggestion that AI is an epochal rupture is only modestly accurate, then I don’t really see what the alternative is.

What does this mean? And then, table-flipping time:

As we have elaborated in this conversation, we live in philosophically discontinuous times. The world has been outgrowing the concepts we have lived by for some time now.

We only live in “philosophically discontinuous times” if you haven’t been paying attention, and haven’t done your homework. Another reason to avoid techbro-adjacent philosophising. It’s just a waste of time.

Source: NOEMA magazine

Image: CC-BYAnne Fehres and Luke Conroy & AI4Media / Better Images of AI / Data is a Mirror of Us /

That mask is kind of coming off in all sorts of ways now

I’d highly recommend listening to Helen Beetham’s latest podcast where she’s in conversation with Audrey Watters talking about AI. As you would expect, they eloquently critique AI as a tool of political and economic power, reinforcing right-wing authoritarianism, labour control, and racial hierarchies. However, the episode covers AI’s deep ties to military surveillance, eugenics, and Silicon Valley libertarianism, with them both arguing that it serves corporate and state interests rather than public good.

The second half of the podcast episode was my favourite, where they highlight how AI in education standardises learning, erases diversity (“the bell curve of banality”), and reinforces existing biases, particularly privileging male whiteness. The myth of AI as a ‘neutral’ or ‘liberating force’ is well and truly skwered, with them instead positioning ‘Luddism’ as a form of resistance against its exploitative tendencies.

I’ve pulled out one particular exchange from the episode which comes after Helen mentions Sam Altman’s response to DeepSeek r1 — something that has been likened to a ‘Sputnik moment’. The insight I appreciate is the comparison to crypto, which Audrey says was “almost too literal” in terms of being “too obvious of a con”.

Helen Beetham: OK. So, well, it’s kind of predictable, but I think the underlying message is really interesting. So effectively what he says is great. That’s great. They’re going to challenge us to do this at smaller scale. But we still need the build out. We absolutely need every inch of data centre we can have, and we need every piece of compute we can have because we’re going to need a lot of AI. And I think this is the moment where the mask starts to slip, you know, because it’s been clear for over a year that they’re not interested in a viable product. They don’t care whether the use cases work or not. Not except kind of rhetorically and incidentally. They don’t care if it’s valuable. They don’t care what it fucks up. They care about controlling data and compute. And it’s a great much better than crypto was. It seems to be much more effective than crypto at amassing that intentionality, that state will, that capital in one place to build out the biggest possible amount of data centres that are under the control of these corporations in alliance with these militarised states. And then at the same time, to control massive amounts of amounts of data and that is the underlying project. I feel that that mask is kind of coming off in all sorts of ways now. I could say something about how that plays out in the UK, but I’d really like to hear what you think.

Audrey Watters: Well, I think it’s interesting that the crypto stuff was almost too literal, right? Because this was about the creation of money. Like, literally we’re going to make up a new currency, and wrest power away from the traditional arbiters of money, the government. So it was almost like too nakedly literal. But with the generative AI, now we’re just making up, you know, students' essays. We’re just creating videos, and somehow it seems like a less overt power grab. I mean, I think for obviously for people in education, for people who work in creative industries, it’s an obvious power grab, but I think that it’s almost as though the cryptocurrency was too much of a con. It was too obvious of a con.

Source: imperfect offerings podcast

Image: Better Images of AI

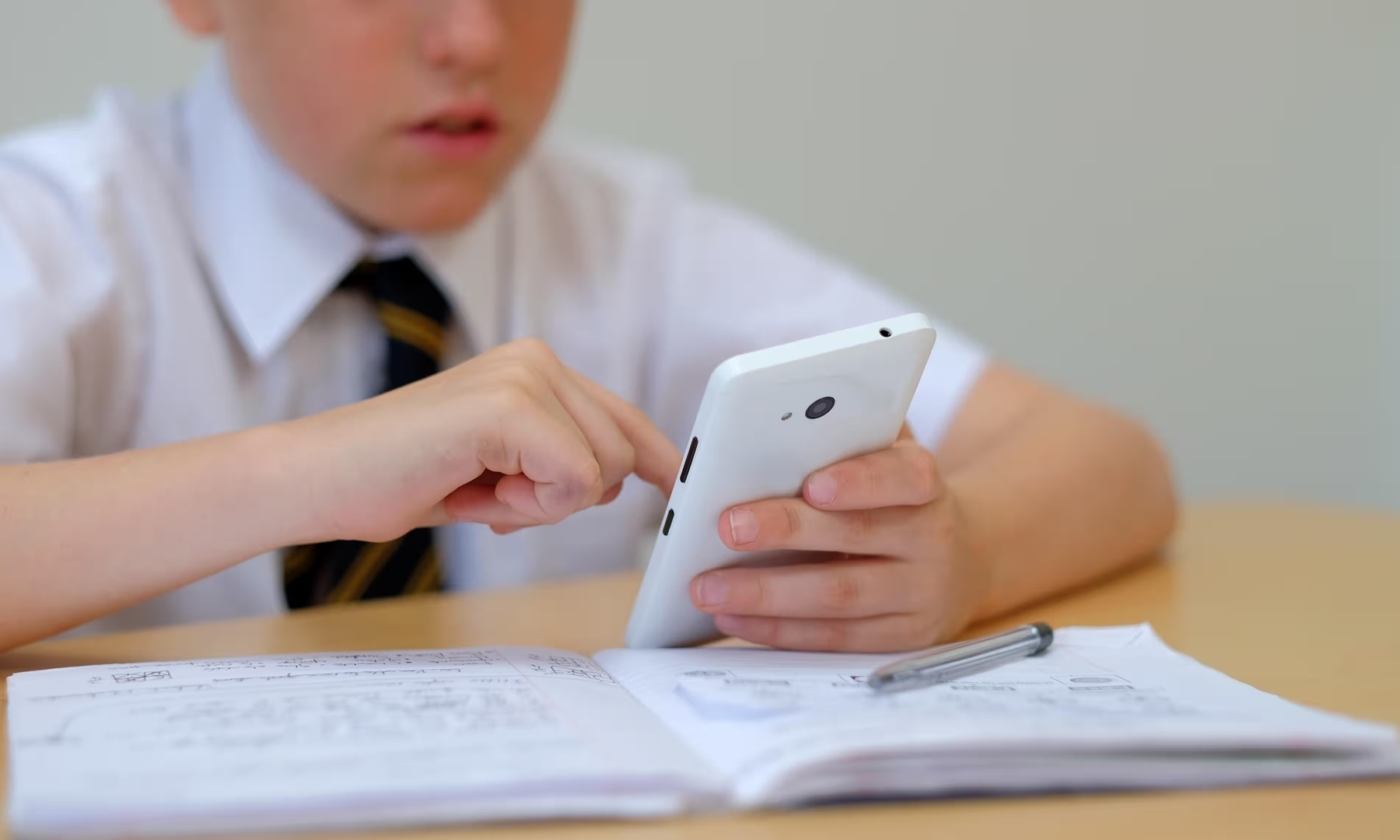

There is no evidence that restrictive school policies are associated with overall phone and social media use or better mental wellbeing in adolescents

I usually find abstracts on academic papers a bit rubbish, but this ‘summary’ at the top of a research study is aces. As many people in the UK will have seen in the news over the last week, a study has shown that there’s “no evidence that restrictive school policies are associated with overall phone and social media use or better mental wellbeing in adolescents. As a result, “the findings do not provide evidence to support the use of school policies that prohibit phone use during the school day in their current form.”

This, of course, does not chime with what the public (parents, politicians, etc.) want to hear, so I imagine it will be widely ignored. In fact, when this was reported on in a radio news bulletin I heard, they immediately cut to a soundbite from a headteacher who had implemented a “no phones” policy who basically said it had worked for them. There are many problems with smartphone uses by teenagers in schools. But then there are many problems with schools.

Background: Poor mental health in adolescents can negatively affect sleep, physical activity and academic performance, and is attributed by some to increasing mobile phone use. Many countries have introduced policies to restrict phone use in schools to improve health and educational outcomes. The SMART Schools study evaluated the impact of school phone policies by comparing outcomes in adolescents who attended schools that restrict and permit phone use.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional observational study with adolescents from 30 English secondary schools, comprising 20 with restrictive (recreational phone use is not permitted) and 10 with permissive (recreational phone use is permitted) policies. The primary outcome was mental wellbeing (assessed using Warwick– Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale [WEMWBS]). Secondary outcomes included smartphone and social media time. Mixed effects linear regression models were used to explore associations between school phone policy and participant outcomes, and between phone and social media use time and participant outcomes. Study registration: ISRCTN77948572.

Findings: We recruited 1227 participants (age 12–15) across 30 schools. Mean WEMWBS score was 47 (SD = 9) with no evidence of a difference between groups (adjusted mean difference −0.48, 95% CI −2.05 to 1.06, p = 0.62). Adolescents attending schools with restrictive, compared to permissive policies had lower phone (adjusted mean difference −0.67 h, 95% CI −0.92 to −0.43, p = 0.00024) and social media time (adjusted mean difference −0.54 h, 95% CI −0.74 to −0.36, p = 0.00018) during school time, but there was no evidence for differences when comparing usage time on weekdays or weekends.

Interpretation: There is no evidence that restrictive school policies are associated with overall phone and social media use or better mental wellbeing in adolescents. The findings do not provide evidence to support the use of school policies that prohibit phone use during the school day in their current form, and indicate that these policies require further development.

Source: The Lancet

Image: True Images/Alamy (via The Guardian)

Technology is a means of spreading misinformation, not the cause of misinformation

As a technologist and educator (former History teacher!) who wrote his doctoral thesis on digital literacies, this article couldn’t be any more in my sweet spot if it tried. Dr Gordon McKelvie talks about his British Academy project about misinformatoin, focusing on queens “because they were prominent enough figures to be spoken about and blamed for the country’s ills.”

Although only coined in 2013, Brandolini’s law has always been in full effect: “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it." At least we live in a time when things can, in theory, be rebutted and debunked quickly. Back in medieval times, people would believe misinformation for years — if not their entire lives.

While a focus on the immediate problems confronting democratic states dealing with the spread of conspiracy theories is essential, we should not lose sight of the fact that misinformation was around long before the internet. If we look back into the distant past, we see the spread of conspiracy theories have been a common feature throughout human history. Technology is a means of spreading misinformation, not the cause of misinformation. […]

A key finding has been that fake news often becomes accepted historical fact. An example that illustrates this is the death of Anne Neville, wife of the infamous Richard III. We do not know the exact cause of her death, but it was probably natural causes. One contemporary source, however, claimed that the king needed to deny poisoning her in order to marry his niece. This is the only near-contemporary reference to such an event, written by the hostile Crowland chronicler . By the time Shakespeare was writing his ‘The Tragedy of Richard III’ a century later, this had become an accepted historical fact. Here, we see something that began as a piece of misinformation in the fifteenth century transformed into an accepted historical fact in the sixteenth century. […]

When we look elsewhere in medieval Europe, we see other examples of misinformation premised on existing prejudices. During the First Crusade, mistrust between the Catholic crusaders and the Greek Orthodox Byzantine Empire led to conspiracy theories that the Byzantines were colluding with Muslims against their fellow Christians. When the first wave of the Black Death hit Europe in 1348, Jews were thought to have spread the disease by poisoning wells, simply to kill Christians. In both examples, pre-existing beliefs and fears meant that misinformation and conspiracy theories flourished quickly. […]

Misinformation was a key feature of medieval politics and society. Examining the spread of fake news, or conspiracy theories, in the centuries before even the printing press, never mind the internet, helps us understand how they flourish and their appeal. […]

Historians have an important part to play in fleshing out our understanding of misinformation. We are indeed living in an age of mistrust, but certainly not the first, and almost definitely not the last.

Source: The British Academy

Image: Walters Art Museum

Once you have a 360 view, you can redirect resources to insiders and cut off the opposition

I’ve held off posting anything about what’s currently going on in the USA at the moment, as apparently it’s all very confusing even if you’re paying full attention. What did make me sit up and take notice, though, was Jason Kottke’s use of screengrab from Mad Max: Fury Road when summarising a Bluesky thread by Abe Newman about Elon Musk’s seizure of key parts of the government’s information systems.

For those who haven’t seen the film (one of my favourites, especially the Black & Chrome Edition), it’s the perfect analogy. A character by the name of Immortan Joe, a dictator in a post-apocalyptic landscape, who is revered as a god by his followers. He dominates the economy by controlling the only supply of fresh water, which he turns on from time to time, saying “Do not, my friends, become addicted to water. It will take hold of you, and you will resent its absence!" I’ve included a gif above that shows the moment from the film.

Newman links to reporting that detail that these operations are controlled by Musk: payment, personnel, and operations. But seeing them as part of a bigger strategy is important:

The first point is to make the connection. Reporting has seen these as independent ‘lock outs’ or access to specific IT systems. This seems much more a part of a coherent strategy to identify centralized information systems and control them from the top.

Newman continues:

So what are the risks. First, the panopticon. Made popular by Foucault, the idea is that if you let people know that they are being watched from a central position they are more likely to obey. E.g. emails demanding changes or workers will be added to lists…

The second is the chokepoint. If you have access to payments and data, you can shut opponents off from key resources. Sen Wyden sees this coming.

Divert to loyalists. Once you have a 360 view, you can redirect resources to insiders and cut off the opposition.

Source: Kottke.org

Clinical studies have indicated that creatine might have an antidepressant effect

Along with about six different supplements, I add creatine to my protein smoothies every day I do exercise. Which, to be fair, is most days ending in a ‘y’. Too much of the white powder and I get angry but, as a male vegetarian, it’s important that I get some in my diet.

It turns out that creatine isn’t just good for building and maintaining muscle mass, though. It turns out that it’s also good for mental health, too — and combining it with various forms of therapy is especially beneficial.

More recently, researchers have begun to look at the broader systemic effects of creatine supplementation. Of particular interest has been the relationship between creatine and brain health. Following the discovery of endogenous creatine synthesis in the human brain, research quickly moved to understand what role this compound plays in things like cognition and mood.

Most studies linking brain benefits to creatine supplementation are either small or preliminary but there are enough clues to suggest that something positive could be going on here. For example, one oft-cited clinical trial from 2012 found creatine supplementation can effectively augment anti-depressant treatment. The trial was small (just 52 subjects, all women) but after eight weeks it found those subjects taking creatine supplements with their SSRI antidepressant were twice as likely to achieve remission from depression symptoms compared to those just taking antidepressants.

A recent article reviewing the research on creatine supplementation and depression pointed to several physiological mechanisms that could plausibly explain how this compound could improve mental health. Alongside citing several small trials that found positive results from creatine supplementation, the article concludes by stating: “Creatine is a naturally occurring organic acid that serves as an energy buffer and energy shuttle in tissues, such as brain and skeletal muscle, that exhibit dynamic energy requirements. Evidence, deriving from a variety of scientific domains, that brain bioenergetics are altered in depression and related disorders is growing. Clinical studies in neurological conditions such as PD [Parkinson’s Disease] have indicated that creatine might have an antidepressant effect, and early clinical studies in depressive disorders – especially MDD [Major Depressive Disorder] – indicate that creatine may have an important antidepressant effect.”

Source: New Atlas

Image: HowToGym

The idea that this might in any way appeal to 'newcomers' is bananas to me

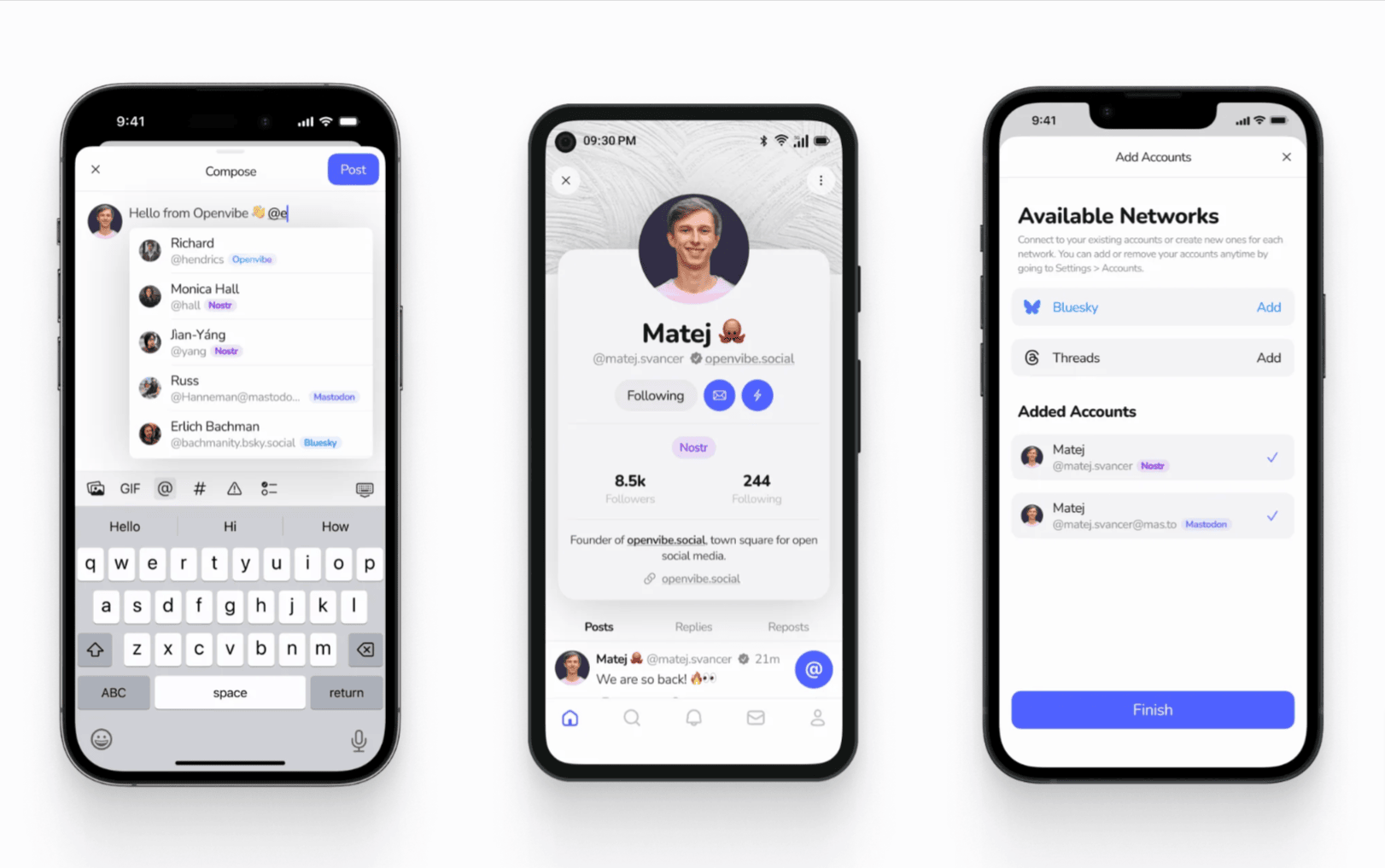

It’s hard not to agree with John Gruber’s analysis of Openvibe, an app that allows you to mash together all of the different decentralised social networks (Mastodon, Bluesky, Threads, etc.) into one timeline. He doesn’t like it, and I have never liked the idea.

That’s partly because it’s confusing, but even if you managed to provide a compelling UX, the rhetorics of interactive communication are completely different on social networks. The way people interact on one social network use different norms and approaches than others. That means different literacies are involved. I’d argue that mashing it all together only really serves people who wish to ‘broadcast’ messages to multiple places at the same time.

I really don’t see the point of mashing the tweets from two (or more!) different social networks into one unified timeline. To me it’s just confusing. I don’t love the current situation where three entirely separate, thriving social networks are worth some portion of my attention (not to mention that a fourth, X, still kinda does too). But when I use each of these platforms, I want to use a client that is dedicated to each platform. These platforms all have different features, to varying degrees, and they definitely have different vibes and cultural norms. Pretending that they all form one big (lowercase-m) meta platform doesn’t make that pretense cohesive. Mashing them all together in one timeline isn’t simpler. It sounds simpler but in practice it’s more cacophonous.

The idea that this might in any way appeal to “newcomers” is bananas to me. The concept of streaming multiple accounts from multiple networks into one timeline is by definition a bit advanced. In my experience, for very obvious reasons, casual social network users only use the first-party client. They’re confused even by the idea of using, say, an app named Ivory to access a social network called Mastodon. The idea of explaining to them why they might want to use an app named Openvibe to access Mastodon, Bluesky, and Threads (and the weirdo blockchain network Nostr) is like trying to explain to your dog why they should stay out of the trash. There’s a market for third-party clients (or at least I hope there is), but that market is not made up of “newcomers”.

Source: Daring Fireball

The inevitable cracks in a rigid software logic that enables the surprising, delightful messiness of humanity to shine through

I’ve been following the development of Are.na since the early days of leading the MoodleNet project. It’s a great example of a platform that serves a particular niche of users (“connected knowledge collectors”) really well.

In this Are.na editorial, Elan Ullendorff — a designer, writer, and educator — talks about the course he teaches. In it, he helps students research and map algorithms, before writing their own, and releasing them to the world.

I write a newsletter, teach a course, and run workshops all called “escape the algorithm.” The implicit joke of the name’s particularity (not “escape algorithms” but “escape the algorithm”) is that living outside of algorithms isn’t actually possible. An algorithm is simply a set of instructions that determines a specific result. The recommendation engine that causes Spotify to encourage you to listen to certain music is a cultural sieve, but so were, in a way, the Billboard charts and radio gatekeepers that preceded it. There have always been centers of power, always been forces that exert gravitational pulls on our behavior.

The anxiety isn’t determined by the presence or absence of code. It comes from a lack of transparency and control. You are susceptible whether or not TikTok exists, whether or not you delete it. Logging off is one tool, but it will not alone cure you.

Instead of withdrawing, I encourage my students to dive deeper, engaging with platforms as if they were close reading a work of literature. In doing so, I believe that we can not only better understand a platform’s ideological premises, but also the inevitable cracks in a rigid software logic that enables the surprising, delightful messiness of humanity to shine through. And in so doing, we might move beyond the flight response towards a fight response. Or if it is a flight response, let it be a flight not just away from something, but towards something.

[…]

Resisting the paths most traveled invites us to look at the platforms we use with a critical eye, leading us to new forms of critique, making visible parts of the world and culture that are out of our view, and inspiring entirely new ways of navigating the web.

Take Andrew Norman Wilson’s ScanOps, a collection of Google Books screenshots that include the hands of low-paid Google data entry workers, or Chia Amisola’s The Sound of Love, which curates evocative comments on Youtube songs. Then there’s Riley Walz’s Bop Spotter (a commentary on ShotSpotter, gunshot detection microphones often licensed by city governments), a constantly Shazam-ing Android phone hidden on a pole in the Mission district.

Source: Are.na

Image: Андрей Сизов

⭐ Become a Thought Shrapnel supporter!

Hi everyone, Doug here. Just to let you know that it’s now possible to support Thought Shrapnel on a monthly basis!

Don’t worry, nothing’s changing other than your ability to ensure the sustainability of this publication, receive a holographic sticker to go on your water bottle (or whatever), and have your name listed as a supporter.

We used to have around 60 supporters of Thought Shrapnel back in the day, so I hope you’ll consider becoming one of the first to get this new (rare!) holographic sticker. This is part of a little February experimentation…

Description of Things and Atmosphere

My daughter was complaining that, now she’s in high school, her English teacher demands more of her writing. I happened to have just read a post at Futility Closet about the notebooks of F. Scott Fitzgerald which gives examples of him coming up with vividly atmospheric descriptions of scenes. I shared it with her, so hopefully she’ll use it as inspiration.

While I’m not a fan of overly-long descriptions just for the sake of it, this writing is sublime. It makes me want to re-read The Great Gatsby.

In the light of four strong pocket flash lights, borne by four sailors in spotless white, a gentleman was shaving himself, standing clad only in athletic underwear upon the sand. Before his eyes an irreproachable valet held a silver mirror which gave back the soapy reflection of his face. To right and left stood two additional menservants, one with a dinner coat and trousers hanging from his arm and the other bearing a white stiff shirt whose studs glistened in the glow of the electric lamps. There was not a sound except the dull scrape of the razor along its wielder’s face and the intermittent groaning sound that blew in out of the sea.

Source: The Notebooks of F. Scott Fitzgerald

Image: Illia Plakhuta

Cozy comfort for gamers

More articles about games should be games themselves, in my opinion! I loved this, and there’s a write-up of how and why it was created at here.

I spend enough times on screens, so haven’t really got into the ‘cozy’ genre, but I know that it’s a huge thing. Games that you can play on your own terms, provide a bit of escapism, are (as the article describes) proven to be as good as meditation and other forms of deep relaxation.

The gaming industry is larger than the film and music industries combined globally. A growing sector is the subgenre dubbed “cozy games.” They are marked by their relaxing nature, meant to help players unwind with challenges that are typically more constructive than destructive. Recent research explores whether this style of game, along with video games more generally, can improve mental health and quality of life.

These play-at-your-own-pace games attract both longtime gamers and newcomers. […]

There’s no hard definition for a “cozy game.” If the game gives the player a cozy, warm feeling then it fits.

[…]

These games can provide a space for people to connect in ways they may not in the real world. Suzanne Roman, who describes herself as an autistic advocate, said gaming communities can be lifelines for neurodivergent people, including her own autistic daughter who celebrated her 18th birthday in lockdown. “I think it’s just made them more confident people, who feel like they fit in socially. There’s even been relationships, of course, that have formed in the real world out of this.”

Source: Reuters

A large public domain image-text dataset to train frontier LLM models

Yesterday, after a conversation on the #ai channel in WAO’s Slack, I published Ways of categorising ethical concerns relating to generative AI. There was some pushback on Mastodon.

Alan Levine asked if I knew of any LLMs which say they’re trained on “open data” and where you can actually see the sources. It’s a good point, and I do know of one, which is Public Domain 12M (or PD12M for short). LLMs are a class of technologies, so (as I was trying to get at in my original post) we should be clear and specific in our objections to them.

Although I don’t share the concern, I understand the position which could be broadly stated as: “I have a problem with LLM datasets being scraped from the open web without the explicit consent of copyright holders.” But that’s not a position against LLMs per se. It’s an objection based on the copyright status of the ingested data.

At 12.4 million image-caption pairs, PD12M is the largest public domain image-text dataset to date, with sufficient size to train foundation models while minimizing copyright concerns. Through the Source.Plus platform, we also introduce novel, community-driven dataset governance mechanisms that reduce harm and support reproducibility over time.

Source: Source.Plus

Strava for Stoics?

Matt Webb is, like me, over 40 years of age. Although some would argue differently, it’s a time when you realise that your fastest days are behind you. So apps like Strava reminding you that you’re not quite as fast as you were a few years ago isn’t… particularly helpful.

There’s definitely a gap in the market for fitness apps for people who are no longer spring chickens and, although they like to challenge themselves occasionally, aren’t trying to smash it every time they go out for a run, cycle, or to the gym. I also appreciate Webb’s related point that there comes a time when reminders about things in life are just a bit painful. The opportunity not to be reminded about things would be nice.

Part of getting older is finding that my PBs each time I train up - personal bests - are not as quick as they were before. […]

I’m currently trying to increase my baseline endurance and went out for a 17 mi run a few days ago. Paused to take photos of the Thames Barrier and a rainbow, no stress. Beautiful. Felt ok when I finished – hey I made it back! Wild!

Then Strava showed me the almost identical run from exactly 5 years ago, I’d forgotten: a super steady pace, a whole minute per mile faster than this week’s tough muddle through. […]

Our quantified self apps (Strava is one) are built by people with time on their side and capacity to improve. A past achievement will almost certainly remind you of a happy day that can be visited again or, in the rear view mirror, has been joyfully surpassed. But for older people… And I’m not even that old, just past my physical peak… […]

I’m not asking Strava to hide these reminders. I’ve found peace (not as completely as I thought it turns out). But I don’t want to avoid those memories. Reminded, I do remember that time from 2020! It is a happy memory! I like to remember what I could do, even if it is slightly bittersweet! […]

And I’ll bet we’re all having that feeling a little bit, deep down, unnamed and unlocated and unconscious quite often, amplified by using these apps. So many of us are using apps that draw from the quantified self movement (Wikipedia) of the 2010s, in one way or another, and that movement was by young people. Perhaps there were considerations unaccounted for – getting older for one. There will be consequences for that, however subtle.

(Another blindspot of the under 40s: it is the most heartbreaking thing to see birthday notifications for people who are no longer with us. Please, please, surely there is a more humane way to handle this?)

So I can’t help viewing some of the present day’s fierce obsession with personal health and longevity or even brain uploads not as a healthy desire for progress but, amplified by poor design work, as an attempt to outrun death.

Source: Interconnected

Image: Tim Foster

How to Raise Your Artificial Intelligence

This is an absolutely incredible interview of Alison Gopnik (AG) and Melanie Mitchell (MM). Gopnik is a professor of psychology and philosophy and studies children’s learning and development, while Mitchell is a professor of computer science and complexity focusing on conceptual abstraction and analogy-making in AI systems.

There’s so much insight in here, so you’ll have to forgive me quoting it at length. I urge you to go and read the whole thing. The thing that really stood out for me was Gopnik’s philosophical insights based on her experience around child development. Fascinating.

AG: There is an implicit intuitive model that everyday people (including very smart people in the tech world) have about how intelligence works: there’s this mysterious substance called intelligence, and as you have more of it, you gain power and authority. But that’s just not the picture coming out of cognitive science. Rather, there’s this very wide array of different kinds of cognitive capacities, many of which trade off against each other. So being really good at one thing actually makes you worse at something else. To echo Melanie, one of the really interesting things we’re learning about LLMs is that things like grammar, which we might have thought required an independent-model-building kind of intelligence, you can get from extracting statistical patterns in data. LLMs provide a test case for asking, What can you learn just from transmission, just from extracting information from the people around you? And what requires independent exploration and being in the world?

[…]

MM: I like to tell people that everything an LLM says is actually a hallucination. Some of the hallucinations just happen to be true because of the statistics of language and the way we use language. But a big part of what makes us intelligent is our ability to reflect on our own state. We have a sense for how confident we are about our own knowledge. This has been a big problem for LLMs. They have no calibration for how confident they are about each statement they make other than some sense of how probable that statement is in terms of the statistics of language. Without some extra ability to ground what they’re saying in the world, they can’t really know if something they’re saying is true or false.

[…]

AG: Some things that seem very intuitive and emotional, like love or caring for children, are really important parts of our intelligence. Take the famous alignment problem in computer science: How do you make sure that AI has the same goals we do? Humans have had that problem since we evolved, right? We need to get a new generation of humans to have the right kinds of goals. And we know that other humans are going to be in different environments. The niche in which we evolved was a niche where everything was changing. What do you do when you know that the environment is going to change but you want to have other members of your species that are reasonably well aligned? Caregiving is one of the things that we do to make that happen. Every time we raise a new generation of children, we’re faced with this difficulty of here are these intelligences, they’re new, they’re different, they’re in a different environment, what can we do to make sure that they have the right kinds of goals? Caregiving might actually be a really powerful metaphor for thinking about our relationship with AIs as they develop. […]

Now, it’s not like we’re in the ballpark of raising AIs as if they were humans. But thinking about that possibility gives us a way of understanding what our relationship to artificial systems might be. Often the picture is that they’re either going to be our slaves or our masters, but that doesn’t seem like the right way of thinking about it. We often ask, Are they intelligent in the way we are? There’s this kind of competition between us and the AIs. But a more sensible way of thinking about AIs is as a technological complement. It’s funny because no one is perturbed by the fact that we all have little pocket calculators that can solve problems instantly. We don’t feel threatened by that. What we typically think is, With my calculator, I’m just better at math. […]

But we still have to put a lot of work into developing norms and regulations to deal with AI systems. An example I like to give is, imagine that it was 1880 and someone said, all right, we have this thing, electricity, that we know burns things down, and I think what we should do is put it in everybody’s houses. That would have seemed like a terribly dangerous idea. And it’s true—it is a really dangerous thing. And it only works because we have a very elaborate system of regulation. There’s no question that we’ve had to do that with cultural technologies as well. When print first appeared, it was open season. There was tons of misinformation and libel and problematic things that were printed. We gradually developed ideas like newspapers and editors. I think the same thing is going to be true with AI. At the moment, AI is just generating lots of text and pictures in a pretty random way. And if we’re going to be able to use it effectively, we’re going to have to develop the kinds of norms and regulations that we developed for other technologies. But saying that it’s not the robot that’s going to come and supplant us is not to say we don’t have anything to worry about. […]

Often the metaphor for an intelligent system is one that is trying to get the most power and the most resources. So if we had an intelligent AI, that’s what it would do. But from an evolutionary point of view, that’s not what happens at all. What you see among the more intelligent systems is that they’re more cooperative, they have more social bonds. That’s what comes with having a large brain: they have a longer period of childhood and more people taking care of children. Very often, a better way of thinking about what an intelligent system does is that it tries to maintain homeostasis. It tries to keep things in a stable place where it can survive, rather than trying to get as many resources as it possibly can. Even the little brine shrimp is trying to get enough food to live and avoid predators. It’s not thinking, Can I get all of the krill in the entire ocean? That model of an intelligent system doesn’t fit with what we know about how intelligent systems work.

Source: LA Review of Books