AI and work socialisation

I've bolded what I consider to be the most important part of this article by danah boyd. It's a reflection on two different 'camps' when it comes to AI and jobs, but she surfaces an important change that's already happened in society when it comes to the workforce: we just don't train people any more.

Couple this with AI potentially replacing lower-paid jobs (where people might 'learn the ropes while working) and... well, it's going to be interesting.

Source: Deskilling on the Job | danah boydWhile getting into what it means to be human is likely to be a topic of a later blog post, I want to take a moment to think about the future of work. Camp Automation sees the sky as falling. Camp Augmentation is more focused on how things will just change. If we take Camp Augmentation’s stance, the next question is: what changes should we interrogate more deeply? The first instinct is to focus on how changes can lead to an increase in inequality. This is indeed the most important kinds of analysis to be done. But I want to noodle around for a moment with a different issue: deskilling.

[...]

Today, you are expected to come to most jobs with skills because employers don’t see the point of training you on the job. This helps explain a lot of places where we have serious gaps in talent and opportunity. No one can imagine a nurse trained on the job. But sadly, we don’t even build many structures to create software engineers on the job.

However, there are plenty of places where you are socialized into a profession through menial labor. Consider the legal profession. The work that young lawyers do is junk labor. It is dreadfully boring and doesn’t require a law degree. Moreover, a lot of it is automate-able in ways that would reduce the need for young lawyers. But what does it do to the legal field to not have that training? What do new training pipelines look like? We may be fine with deskilling junior lawyers now, but how do we generate future legal professionals who do the work that machines can’t do?

This is also a challenge in education. Congratulations, students: you now have tools at your disposal that can help you cut corners in new ways (or outright cheat). But what if we deskill young people through technology? How do we help them make the leap into professions that require more advanced skills?

[...]

Whether you are in Camp Augmentation or Camp Automation, it’s really important to look holistically about how skills and jobs fit into society. Even if you dream of automating away all of the jobs, consider what happens on the other side. How do you ensure a future with highly skilled people? This is a lesson that too many war-torn countries have learned the hard way. I’m not worried about the coming dawn of the Terminator, but I am worried that we will use AI to wage war on our own labor forces in pursuit of efficiency. As with all wars, it’s the unintended consequences that will matter most. Who is thinking about the ripple effects of those choices?

The party's over for office-based work

In-person working can be energising. But perhaps not every day, for most people? There’s a reason that lots of people have decided to continue to work at home after the pandemic showed them that a different approach was possible.

Take Google. The tech giant threw a massive welcome-back party complete with a Lizzo concert. Sure, it sounds cool, but unless Lizzo will one day be my manager, what does a concert have to do with getting me to my desk day after day after day? Will there be daily concerts? Everyone was isolated for two years. How does attending a concert with people I’ve never met or barely remember better connect me to the company? Being alone in a crowd would actually remind me just how few friends I have at the organization.Source: Wake up, Corporate America: You can’t bribe, threaten, or feed people to get them back in the office | The Boston Globe

One place to rule them all?

Connor Oliver muses on the fact that, never mind the decline in ‘third places’ (or ‘third spaces’ as we’d probably call in them in the UK) there’s a decline in second places/spaces. What happens if you live and work in the same place all of the time?

It’s a real issue, and as he points out, it’s particularly acute if you’re single and don’t have kids. I’ve lived and worked from home since 2012, and from this particular house since 2014. So travel is particularly important to me, as are my kids sporting fixtures!

I don't know who coined the term "third place" and while I don't really care, my understanding is that a third place is something along the lines of a hobby group, sports club, church, barbershop, or other place you go to socialize outside of your first and second places, home and work.Source: A third place? I’m not sure I even have a second anymore. | Muezza.ca[…]

My question is though, what does one do when they no longer even have a second place (work)?

[…]

A not insignificant number of us have seen our first and second place merge into one and we’ve lost much of what made our second place a second place. In some more extreme examples like mine, people have never met their coworkers in person, or even know what some of their co-workers look like.

Hiring people without degrees

This is my commentary on Bryan Alexander’s commentary of an Op-Ed in The New York Times. You’d think I’d be wholeheartedly in favour of fewer jobs requiring a degree and, I am, broadly speaking.

However, and I suppose I should write a more lengthy piece on this somewhere, I am a little concerned about jobs becoming credential-free and experience-free experiences. Anecdotally, I’ve found that far from CVs and resumes being on the decline, they’re being used more than ever — along with rounds and rounds of interviews that seem to favour, well… bullshitters.

At a broader level, I find the Times piece fitting into my peak higher education model in a quiet way. The editorial doesn’t explicitly call for fewer people to enroll in college, but does recommend that a chunk of the population pursue careers without post-secondary experience (or credentials). In other words, should public and private institutions heed the editorial, we shouldn’t expect an uptick in enrollment, but more of the opposite.Source: Employers, hire more people without college degrees, says the New York Times | Bryan AlexanderWhich brings me to a final point. I’ve previously written about a huge change in how Americans think about higher ed. For a generation we thought that the more people get more college experience, the better. Since 2012 or so there have been signs of that national consensus breaking down. Now if the New York Times no longer shares that inherited model, is that shared view truly broken?

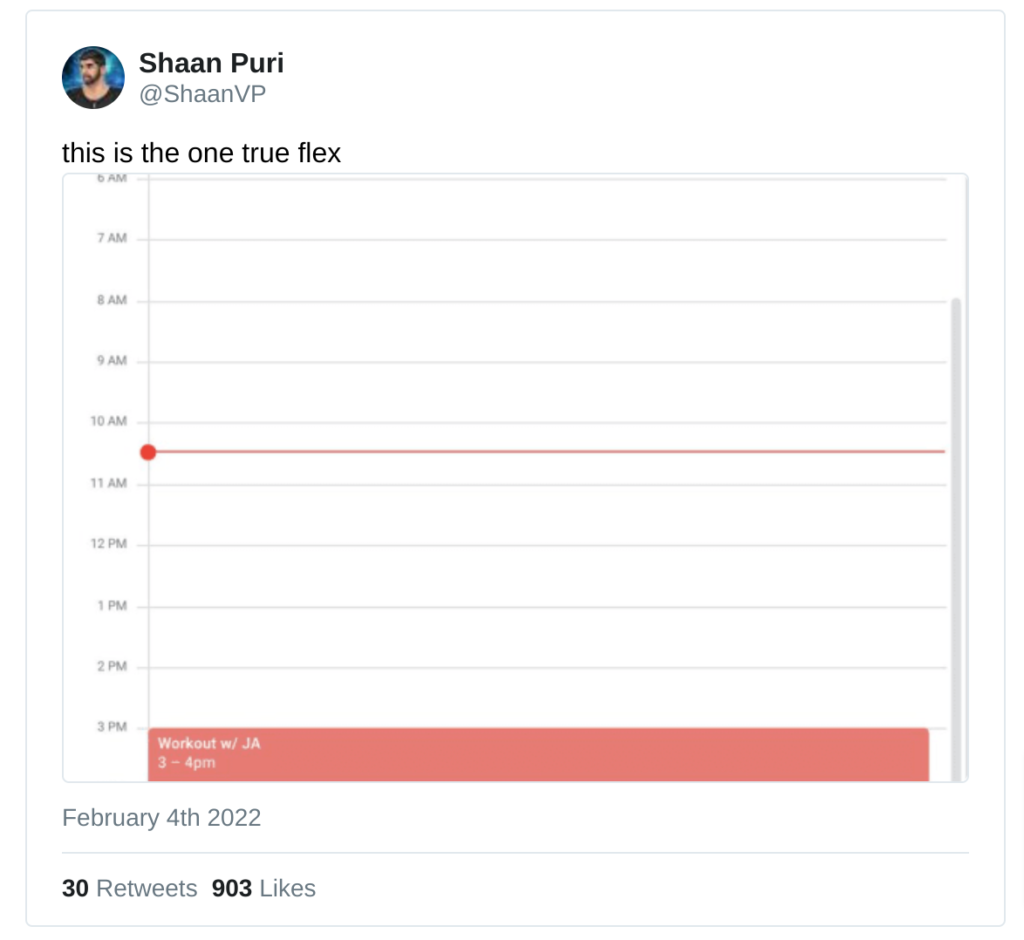

Level 3 busy-ness

Discovered via Kottke, this ‘seven levels of busy’ makes me realise that I don’t really want to be beyond Level 3 most weeks. Level 4 is OK on occasion.

It’s over a decade since I’ve experienced Levels 5 and 6, I reckon. And I’ve never let things get to Level 7.

Level 3: SIGNIFICANT COMMITMENTS I have enough commitments that I need to keep track of them in a tool because I can no longer organically triage. My calendar is a thing I check infrequently, but I do check it to remind myself of the flavor of this particular day.Source: The Seven Levels of Busy | Rands in Repose

Photo: Dan Freeman

Preparation is everything

I used to have a quotation on the wall of my classroom when I was a teacher that has been attributed to various different people, but reads: “Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work."

The point of the quotation is that to have any kind of success in life that isn’t luck-dependent, you have to be ready. That looks different depending on the situation, but (for me at least) involves thinking about different scenarios, what could play out, etc.

This post, found via HN, is from a developer thinking about software projects. But the point he makes is universal: preparing effectively means that you can get on and focus on delivering without having to keep stopping.

Motivation is the willingness to want to do something. This is of course an important first step in potentially being productive. We are better at things we want to do, rather than things we’re forced to do by others, or by our own self discipline.Source: To Be Productive, Be Prepared | Martin RueBut motivation is nothing more than that. It helps us start, but it doesn’t mean we’ll finish, or even produce half of what we want to. Even when we are motivated, if we don’t make enough progress our motivation has a way of epically [sic] disappearing.

[…]

Knowing how to make progress and making progress are two different things, but we often conflate them and treat them as the same thing. We basically jump into the task and start.

[…]

Productivity doesn’t come from feeling motivated, it comes from knowing what you need to do in enough detail that you can complete it without continually stopping and losing your focus.

Image: Brett Jordan

Rituals for moving jobs when working from home

Terence Eden reflects on changing jobs when working from home and how… weird it can be. While I’ve been based from two different converted garages during the past decade, I’ve travelled a lot so it has felt different.

I can imagine, though, if that’s not the case, it can all feel a little bit discombobulating!

One Friday last year, I posted some farewell messages in Slack. Removed myself from a bunch of Trello cards. Had a quick video call with the team. And then logged out of my laptop. I walked out of my home office and sat in my garden with a beer.Source: Job leaving rituals in the WFH era | Terence Eden’s BlogThe following Monday I opened the door to the same office. I logged in to the same laptop. I logged into a new Slack - which wasn’t remarkably different from the old one. Signed in to a new Trello workspace - ditto. And started a video call with my new team.

I’ll admit, It didn’t feel like a new job!

There was no confusing commute to a new office. No having to work out where the toilets and fire exits were. No “here’s your desk - it’s where John used to sit, so people might call you John for a bit”. I didn’t even have to remember people’s names because Zoom showed all my colleagues' names & job titles.

There was no waiting in a liminal space while receptionists worked out how to let me in the building.

In short, there was no meaningful transition for me.

Presenteeism, overwork, and being your own boss

I spend a lot of time on the side of football pitches and basketball courts watching my kids playing sports. As a result, I talk to parents and grandparents from all walks of life, who are interested in me being a co-founder of a co-op — and that, on average, I work five-hour days.

This wasn’t always the case, of course. I’ve been lucky, for sure, but also intentional about the working life I want to create. And I’m here to tell you that unless you at least partly own the business you work for, you’re going to be overworking until the end of your days.

Hidden overwork is different to working long hours in the office or on the clock at home – instead, it’s the time an employee puts into tasks on top of their brief. There are plenty of reasons people take on this extra work: to be up to speed in meetings; appear ‘across issues’ when asked about industry developments; or seem sharp in an environment in which a worker is still trying to establish themselves.Source: The hidden overwork that creeps into so many jobs | BBC WorklifeThere are myriad ways a person’s day job can slip into their non-working hours: think a worker chatting to someone from their industry at their child’s birthday party, and suddenly slipping into networking mode. Or perhaps an employee hears their boss mention a book in a meeting, so they download and listen to it on evening walks for a week, stopping occasionally to jot down some notes.

[…]

However, for many, this overwork no longer feels like a choice – and that’s when things go bad. This can especially be the case, says [Alexia] Cambon [director of research at workplace-consultancy Gartner’s HR practice], when these off-hours tasks become another form of presenteeism – for instance, an employee reading a competitor’s website and sharing links in a messaging channel at night, just so they can signal to their boss they’re always on. “We’re seeing… more employees who feel monitored by their organisations, and then feel like they have to put in extra hours,” she says.

As such, this hidden overwork can do a lot of potential damage if it becomes an unspoken requirement. “If there’s more expectation and burden associated with it, that’s where people are going to have negative consequences,” says Nancy Rothbard, management professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, US. “That’s where it becomes tough on them.”

AI is coming for middle management

It’s hard not to agree with this. Things may play out a little different in the EU, but in the USA and UK I can foresee the middle classes despairing.

Legacy businesses will have to rely on retail and hourly support staff to be able to reduce management head count as a means of freeing up money for implementing automation. In order to do that, they will need to implement AI management tools; chat bots, scheduling, negotiating, training, data collection, diagnostic analysis, etc., before hand.Source: AI will replace middle management before robots replace hourly workers | Chatterhead SaysOtherwise, they will be left to rely on an overly bureaucratic and entrenched middle management layer to do so and that solution is likely to come from outsourcing or consultants. All the while, the retail environment deteriorates as workers are tasked to replace themselves without any additional benefits; service declines, implementation falters, costs go up, more consulting required.

Union formation across the retail landscape will force corporations to reduce management head count and implement AI management solutions which focus on labor relations. The once fungible and disposable retail worker will be transformed into a highly sought after professional who will be relied upon specifically for automation implementation.

Image: DeepMind

Being 'quietly fired' at work

I’ll not name the employer, and this wasn’t recent, but I’ve been ‘quietly fired’ from a job before. I never really knew why, other than a conflict of personalities, but there was no particular need for pursuing that path (instead of having a grown-up conversation) and it definitely had an impact on my mental health.

I think part of the reason this happens is because a lot of organisations have extremely poor HR functions and managers without much training. As a result, they muddle through, avoiding conflict, and causing more problems as a result.

There may not always be a good fit between jobs and the workers hired to do them. In these cases, companies and bosses may decide they want the worker to depart. Some may go through formal channels to show employees the door, but others may do what Eliza’s boss did – behave in such a way that the employee chooses to walk away. Methods may vary; bosses may marginalise workers, make their lives difficult or even set them up to fail. This can take place over weeks, but also months and years. Either way, the objective is the same: to show the worker they don’t have a future with the company and encourage them to leave.Source: The bosses who silently nudge out workers | BBC WorklifeIn overt cases, this is known as ‘constructive dismissal’: when an employee is forced to leave because the employer created a hostile work environment. The more subtle phenomenon of nudging employees slowly but surely out of the door has recently been dubbed ‘quiet firing’ (the apparent flipside to ‘quiet quitting’, where employees do their job, but no more). Rather than lay off workers, employers choose to be indirect and avoid conflict. But in doing so, they often unintentionally create even greater harm.

[…]

An employee subtly nudged out the door isn’t without legal recourse, either. “If you were to look at each individual aspect of quiet firing, there’s likely nothing serious enough to prove an employer breach of contract,” says Horne. “However, there’s the last-straw doctrine: one final act by the employer which, when added together with past behaviours, can be asserted as constructive dismissal by the employee.”

More immediate though, is the mental-health cost to the worker deemed to be expendable by the employer – but who is never directly informed. “The psychological toll of quiet firing creates a sense of rejection and of being an outcast from their work group. That can have a huge negative impact on a person’s wellbeing,” says Kayes.

What does work look like? (redux)

If you’re digging a hole or otherwise doing manual work, it’s obvious when you’re working and when you’re not. The same is true, to a great extent, when teaching (my former occupation).

Doing what I do now, which is broadly under the banner of ‘knowledge work’, it can be difficult for others to see the difference between when I’m working and when I’m not. This is one of the reasons that working from home is so liberating.

The funny thing is, sitting alone thinking doesn’t “look” like work. Even more so if it’s away from your computer.Source: What “Work” Looks Like | Jim Nielsen’s Blog[…]

I recently had a conversation with a long-time colleague, someone I know and respect. I found it interesting that even he, who has worked in software since the 90’s, still felt odd when he wasn’t at his computer “working”. After decades of experience, he knew and understood that the most meaningful conceptual progress he made on problems was always away from his computer: on a run, in the shower, laying in bed at night. That’s where the insight came. And yet, even after all these years, he still felt a strange obligation to be at his computer because that’s too often our the metal image of “working”.

Image: Charles Deluvio

Organisational design: the floor is lava

Coda Hale was, until last year, Principal Engineer at MailChimp. As a result, they seamless mix in words and equations in this article that betray an engineering background.

You shouldn’t let that put you off, though, as this deep dive into organisational design is absolutely worth it. I want to quote two sections in particular, but go and read the whole thing!

The first bit, is the difference between the way that management visualises the structure of an organisation versus how it actually works. Hale explains this as the difference between things that look like they’re working in parallel but which actually sequential:

As with writing highly-concurrent applications, building high-performing organizations requires a careful and continuous search for shared resources, and developing explicit strategies for mitigating their impact on performance.I’ve definitely been in the situation as a consultant multiple times where we’re used as a way to get around organisational inefficiencies. But then when you plug the work back into the organisation, you have to sit and wait until the next bit of work comes along. There’s no rhythm to it, which is annoying for everyone. It’s incoherent.A commonly applied but rarely successful strategy is using external resources–e.g. consultants, agencies, staff augmentation–as an end-run around contention on internal resources. While the consultants can indeed move quickly in a low-contention environment, integrating their work product back into the contended resources often has the effect of… a quadratic spike in wait times which increases utilization which in turn produces a superlinear spike in wait times… Successful strategies for reducing contention include increasing the number of instances of a shared resource (e.g., adding bathrooms as we add employees) and developing stateless heuristics for coordinating access to shared resources (e.g., grouping employees into teams).

As with heavily layered applications, the more distance between those designing the organization and the work being done, the greater the risk of unmanaged points of contention. Top-down organizational methods can lead to subdivisions which seem like parallel efforts when listed on a slide but which are, in actuality, highly interdependent and interlocking. Staffing highly sequential efforts as if they were entirely parallel leads to catastrophe.

So the best thing to do, whether you’re working with outside people/orgs or not, is to limit the number of people who need to be consulted as part of processes:

The only scalable strategy for containing coherence costs is to limit the number of people an individual needs to talk to in order to do their job to a constant factor.This is an article I’ll be coming back to!In terms of organizational design, this means limiting both the types and numbers of consulted constituencies in the organization’s process. Each additional person or group in a responsibility assignment matrix geometrically increases the area of that matrix. Each additional responsibility assignment in that matrix geometrically increases the cost of organizational coherence.

It’s also worth noting that these pair-wise communications don’t need to be formal, planned, or even well-known in order to have costs. Neither your employee handbook nor your calendar are accurate depictions of how work in the organization is done. Unless your organization is staffed with zombies, members of the organization will constantly be subverting standard operating procedure in order to get actual work done. Even ants improvise. An accurate accounting of these hidden costs can only be developed via an honest, blameless, and continuous end-to-end analysis of the work as it is happening.

Source: Work Is Work | codahale.com

Image: CC BY-NC-SA LockRikard

Organisational design: the floor is lava

Coda Hale was, until last year, Principal Engineer at MailChimp. As a result, they seamless mix in words and equations in this article that betray an engineering background.

You shouldn’t let that put you off, though, as this deep dive into organisational design is absolutely worth it. I want to quote two sections in particular, but go and read the whole thing!

The first bit, is the difference between the way that management visualises the structure of an organisation versus how it actually works. Hale explains this as the difference between things that look like they’re working in parallel but which actually sequential:

As with writing highly-concurrent applications, building high-performing organizations requires a careful and continuous search for shared resources, and developing explicit strategies for mitigating their impact on performance.I’ve definitely been in the situation as a consultant multiple times where we’re used as a way to get around organisational inefficiencies. But then when you plug the work back into the organisation, you have to sit and wait until the next bit of work comes along. There’s no rhythm to it, which is annoying for everyone. It’s incoherent.A commonly applied but rarely successful strategy is using external resources–e.g. consultants, agencies, staff augmentation–as an end-run around contention on internal resources. While the consultants can indeed move quickly in a low-contention environment, integrating their work product back into the contended resources often has the effect of… a quadratic spike in wait times which increases utilization which in turn produces a superlinear spike in wait times… Successful strategies for reducing contention include increasing the number of instances of a shared resource (e.g., adding bathrooms as we add employees) and developing stateless heuristics for coordinating access to shared resources (e.g., grouping employees into teams).

As with heavily layered applications, the more distance between those designing the organization and the work being done, the greater the risk of unmanaged points of contention. Top-down organizational methods can lead to subdivisions which seem like parallel efforts when listed on a slide but which are, in actuality, highly interdependent and interlocking. Staffing highly sequential efforts as if they were entirely parallel leads to catastrophe.

So the best thing to do, whether you’re working with outside people/orgs or not, is to limit the number of people who need to be consulted as part of processes:

The only scalable strategy for containing coherence costs is to limit the number of people an individual needs to talk to in order to do their job to a constant factor.This is an article I’ll be coming back to!In terms of organizational design, this means limiting both the types and numbers of consulted constituencies in the organization’s process. Each additional person or group in a responsibility assignment matrix geometrically increases the area of that matrix. Each additional responsibility assignment in that matrix geometrically increases the cost of organizational coherence.

It’s also worth noting that these pair-wise communications don’t need to be formal, planned, or even well-known in order to have costs. Neither your employee handbook nor your calendar are accurate depictions of how work in the organization is done. Unless your organization is staffed with zombies, members of the organization will constantly be subverting standard operating procedure in order to get actual work done. Even ants improvise. An accurate accounting of these hidden costs can only be developed via an honest, blameless, and continuous end-to-end analysis of the work as it is happening.

Source: Work Is Work | codahale.com

Image: CC BY-NC-SA LockRikard

WFH from anywhere

Winter in the UK isn’t much fun, so if we didn’t have kids I would absolutely be working from a different country for part of it. Why not?

This is not a new thing: when I worked at Mozilla (2012-15) I almost moved to Gozo, a little island off Malta, as I could work from anywhere. So long as people are productive, and you can interact with them at times that work for everyone, what’s the problem?

Two-plus years into the pandemic, companies all around the world are starting to ask—and sometimes demand—that their employees return to the office. In response, many employees have resisted, citing reduced commute times, better work-life balance, and a greater ability to concentrate at home.Source: Some WFH Employees Have a Secret: They Now Live in Another Country | VICEBut for an unknown number of people, there is another reason as well: They can’t come in, because they secretly don’t live in the same state or even country anymore.

The issue is larger than it may seem, and many companies are struggling to deal with “employees relocating themselves to ‘nicer’ places to work without letting the business know,” said Robby Wogan, the CEO of global mobility company MoveAssist. One survey performed on behalf of the HR company Topia found that as many as 40 percent of HR professionals had recently discovered that employees were working outside their home state or country, and that only 46 percent were “very confident” they know where most of their workers are, down from 60 percent just last year.

That uncertainty appears justified. In the same survey, 66 percent of the 1,500 full-time employees surveyed in the U.S. and U.S. said they did not tell human resources about all the dates they worked outside of their state or country, and 94 percent said they believe they should be able to work wherever they want if their work gets done.

You should only ever be busy on purpose

If you’re consistently over-stretched, you’re doing it wrong. And if you’re not doing it wrong, your organisation is.

If you are too busy, why? What are you and your team in pursuit of? If you are too busy because of pressure imposed by someone else, why do they believe they should be able to ask more of you?Source: Why are you so busy? | Tom LinghamAre you too busy because the business has expectations for you to deliver by a certain date regardless of the capacity of your team (who are delivering high quality work and always working on the next most important thing as prioritised by the business)? Then that is a conversation that you need to have with your boss and your stakeholders. That is likely unreasonable.

[…]

You and your team should never be so busy that you can’t do your job properly or that you begin to hate your work. Especially if you’re a leader or a leader-of-leaders, then you should actually (yes you should, I’ll die on this hill) have free time to think alone, and to talk and ideate organically with peers. Contrary to popular belief: back-to-back meetings isn’t a badge of honour, it’s a red flag.

Image: DALL-E 2

Being busy isn't a badge of honour

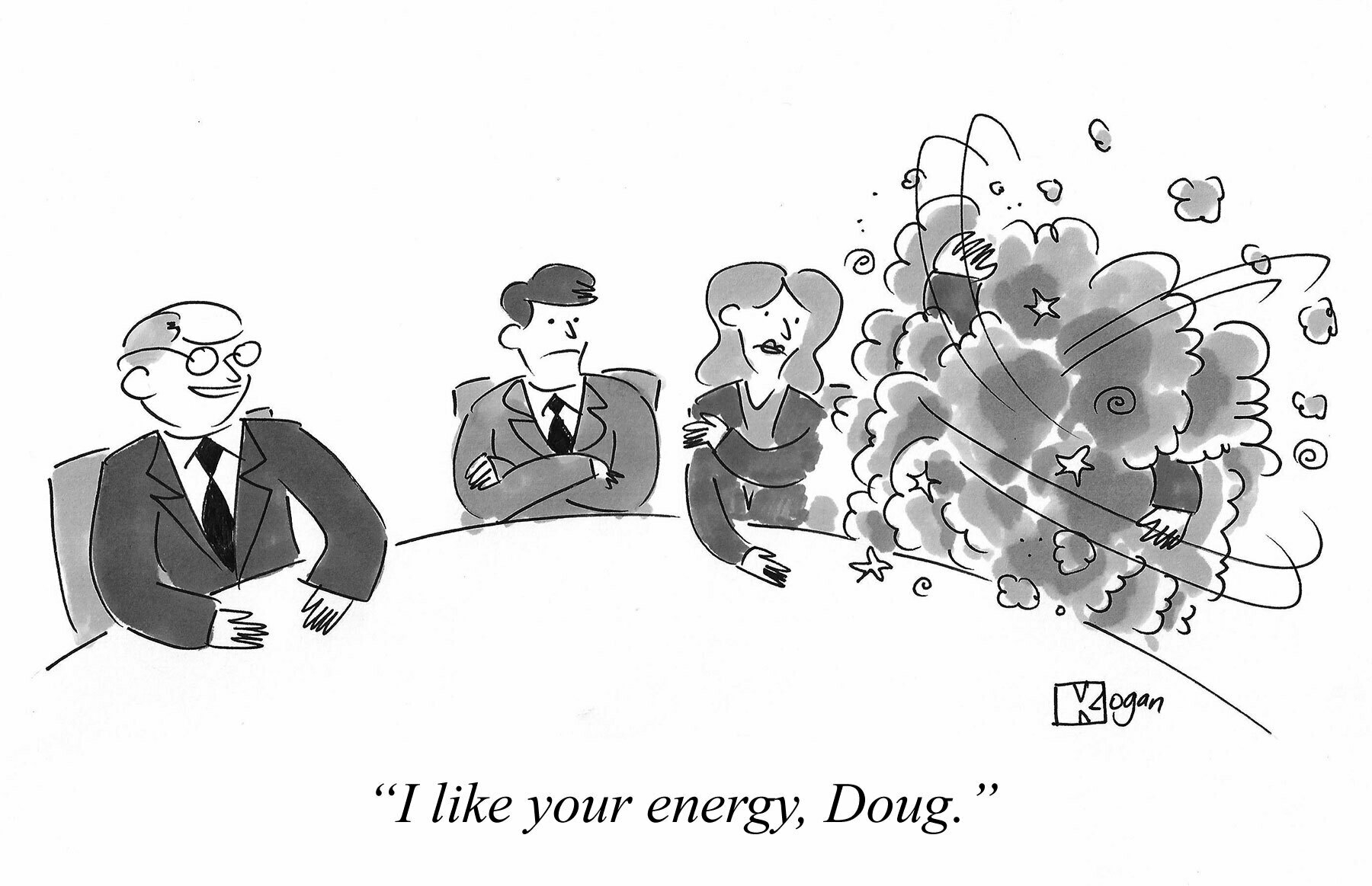

If you think I’m sharing this image because my name is Doug and I find the accompanying image amusing then you’d be 100% correct.

I used to think being swamped was a good sign. I’m doing stuff! I’m making progress! I’m important! I have an excuse to make others wait! Then I realized being swamped just means I’m stuck in the default state, like a ball that settled to a stop in the deepest part of an empty pool, the spot where rainwater has collected into a puddle.Source: Being Swamped is Normal and Not Impressive | Greg KoganBeing swamped means probably not getting enough rest, making things more complicated than they need to be, wasting time on petty decisions, and not thinking deeply about important decisions.

Now, I’m impressed by people who are not swamped. They prioritize ruthlessly to separate what’s most important from everything else, think deeply about those most-important things, execute them well to make a big impact, do that consistently, and get others around them to do the same. Damn, that’s impressive!

Being busy isn't a badge of honour

If you think I’m sharing this image because my name is Doug and I find the accompanying image amusing then you’d be 100% correct.

I used to think being swamped was a good sign. I’m doing stuff! I’m making progress! I’m important! I have an excuse to make others wait! Then I realized being swamped just means I’m stuck in the default state, like a ball that settled to a stop in the deepest part of an empty pool, the spot where rainwater has collected into a puddle.Source: Being Swamped is Normal and Not Impressive | Greg KoganBeing swamped means probably not getting enough rest, making things more complicated than they need to be, wasting time on petty decisions, and not thinking deeply about important decisions.

Now, I’m impressed by people who are not swamped. They prioritize ruthlessly to separate what’s most important from everything else, think deeply about those most-important things, execute them well to make a big impact, do that consistently, and get others around them to do the same. Damn, that’s impressive!

Doomed to live in a Sisyphean purgatory between insatiable desires and limited means

I’m reading The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow. It’s an eye-opening book in many ways, and upends notions of how we see the way that people used to live.

This article suggests that 15-hour working weeks are the norm in egalitarian cultures. While working hours are steadily declining, we’re still a long way off — primarily because our desires and means are out of kilter.

New genomic and archeological data now suggest that Homo sapiens first emerged in Africa about 300,000 years ago. But it is a challenge to infer how they lived from this data alone. To reanimate the fragmented bones and broken stones that are the only evidence of how our ancestors lived, beginning in the 1960s anthropologists began to work with remnant populations of ancient foraging peoples: the closest living analogues to how our ancestors lived during the first 290,000 years of Homo sapiens’ history.Source: The 300,000-year case for the 15-hour week | Financial TimesThe most famous of these studies dealt with the Ju/’hoansi, a society descended from a continuous line of hunter-gatherers who have been living largely isolated in southern Africa since the dawn of our species. And it turned established ideas of social evolution on their head by showing that our hunter-gatherer ancestors almost certainly did not endure “nasty, brutish and short” lives. The Ju/’hoansi were revealed to be well fed, content and longer-lived than people in many agricultural societies, and by rarely having to work more than 15 hours per week had plenty of time and energy to devote to leisure.

Subsequent research produced a picture of how differently Ju/’hoansi and other small-scale forager societies organised themselves economically. It revealed, for instance, the extent to which their economy sustained societies that were at once highly individualistic and fiercely egalitarian and in which the principal redistributive mechanism was “demand sharing” — a system that gave everyone the absolute right to effectively tax anyone else of any surpluses they had. It also showed how in these societies individual attempts to either accumulate or monopolise resources or power were met with derision and ridicule.

Most importantly, though, it raised startling questions about how we organise our own economies, not least because it showed that, contrary to the assumptions about human nature that underwrite our economic institutions, foragers were neither perennially preoccupied with scarcity nor engaged in a perpetual competition for resources.

For while the problem of scarcity assumes that we are doomed to live in a Sisyphean purgatory, always working to bridge the gap between our insatiable desires and our limited means, foragers worked so little because they had few wants, which they could almost always easily satisfy. Rather than being preoccupied with scarcity, they had faith in the providence of their desert environment and in their ability to exploit this.

Productivity is the enemy of creativity

I like the metaphor used in this post of being light a lightbulb: fully one, or off. In fact, not only have I organised my working life to be like this (I can’t work at half pace, and it’s burned me out when I’ve been employed), but this is the advice I give to my kids when they play sports.

“Most people in life are dim lights, they're on but they are not bright. Because they are trying to conserve energy. You should make a choice, you are either on or off. There is either GO time or there is relaxing time. Try to be more binary. You have more energy when it’s Go time" - Andrew “Cobra” Tate.Source: Be Like a Light Bulb: The Importance of Resting Ethic | The Hard Fork by Marvin Liao[…]

Naval [Ravikant] famously said: “Productivity is the Enemy of Creativity”

Rest is absolutely critical for high performance. Without it, it’s like revving your engine until it breaks or blows up. We’re in a new world now where our brains power everything. As the Doomberg crew calls it: “The Gig Economy for Brains.”

Naval again says: “Some of the most creative and productive people I have ever met work in multi-week bursts and then have weeks where they just idle with little done. It’s the nature of the human animal.”

All-in and fully energized OR quiet and at rest. There is no in between. This is a key habit for effective work in the modern day. Don’t be a dim light.

Ian Bogost on hybrid work

I always enjoy Ian Bogost’s articles for The Atlantic as they’re thought-provoking. In this one, he talks about how ‘hybrid work’ is doomed, mainly because The Office is a construct, a way of organising life and work, and heavily invested in the status quo.

A rational assessment of your time and productivity was never quite at issue, and I think it never will be. Companies have been pulling employees back to work in person irrespective of anyone’s well-being or efficiency. That’s because return-to-office plans are not concerned, in any fundamental way, with workers and their plight or preferences. Rather they serve as affirmations of a superseding value—one that spans every industry of knowledge work. If your boss is nudging you to come back to your cubicle, the policy has less to do with one specific firm than with the whole firmament of office life: the Office, as an institution. The Office must endure! To the office we must go.Source: Hybrid Work Is Doomed | The AtlanticThis should be obvious, but somehow it is not: The existence of an office is the central premise of office work, and nothing—not even a pandemic—will make it go away.

[...]Even in the technology sector, where the tools of remote work are manufactured, the Office reigns supreme. Before the pandemic, Big Tech companies doubled down on the sorts of work environments that had been common for almost a century: urban high-rises and suburban office parks. (Think of Microsoft’s campus in Redmond, Washington; Google’s and Facebook’s in Silicon Valley; Apple’s spaceship in Cupertino; and the Salesforce Tower in San Francisco.) Their deluxe office amenities—free food, gymnasiums, medical care, etc.—only underscore this point: The tech industry has a deep investment in the most conservative interpretation of office life.

If the companies that design and build the very foundations for remote work still adhere to the old-fashioned values of the Office, what should we expect from all the rest? It’s still possible that hybridized knowledge work will become the norm, with work-from-home days provided as a perk. But to get there, office workers must organize, and take the goals and power of the Office into account. It does not want to be flexible, and it cares little for efficiency. If the Office makes concessions, they will be minor, or they will take time; hybrid work is not a revolution.