Vaccine Hesitancy as part of a Plague Anthology

I’m not sure who’s behind this website, but it looks good. I appreciated the historical context behind vaccine hesitancy in cultures other than my own provided in the most recent post.

Anti-vaxxers adjacent to conspiracy theorists are nuts, but there’s definitely a communications angle to ensuring the effective roll-out of life-saving vaccines.

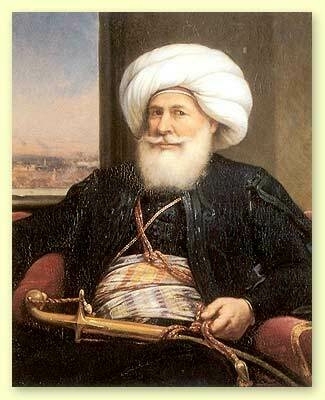

In Egypt, around 1800, there are reports of 60 000 deaths each year. The Ottoman ruler, Muhammad Ali Pasha, began in 1819 to institute a plan for general vaccinations and the logical people to carry this out were the barber-surgeons, known and trusted by the locals. While the Bedouin had long been enthusiastic about protecting their children in this way, the fellahin (peasantry) was reluctant, largely because they did not trust the government and thought it was a way of “marking” their children for conscription. Religious objections and concerns about mixing Muslim and Christian blood also played their part, and attempts to bribe the vaccinators were not uncommon.Source: Vaccine Hesitancy – Egypt 1866 | Plague AnthologyAfter the serious epidemic of 1836, official efforts intensified, with barber-vaccinators being trained and records kept. Gradually, the message got through and by 1850, the decline in child mortality was affecting the population statistics. The following anecdote, describes a perhaps surprising pocket of vaccine hesitancy.

Fractional dosing of COVID vaccines may help more people get immunity faster

The advice to date has, quite rightly, to get any COVID vaccine that’s available to you. For me, that’s meant a double dose of AstraZeneca, and I’m happy about that.

But as the pandemic progresses, we need to be aware that some vaccines are more effective than others. This working paper, building on one published in Nature earlier this year, looks at how ‘fractional dosing’ of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines could reach more people more quickly.

Needless to say, we shouldn’t be in the position where people in less developed countries are getting access to vaccines much more slowly than the rest of the world. But, pragmatically speaking, this may help.

We supplement the key figure from Khoury et al.’s paper to show that fractional doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have neutralizing antibody levels (as measured in the early phase I and phase II trials) that look to be on par with those of many approved vaccines. Indeed, a one-half or one-quarter dose of the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine is predicted to be more effective than the standard dose of some of the other vaccines like the AstraZeneca, J&J or Sinopharm vaccines, assuming the same relationship as in Khoury et al. holds. The point is not that these other vaccines aren’t good–they are great! The point is that by using fractional dosing we could rapidly and safely expand the number of effective doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines.Source: A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective Than a Full Dose of AstraZeneca | Marginal REVOLUTION[…]

One more point worth mentioning. Dose stretching policies everywhere are especially beneficial for less-developed countries, many of which are at the back of the vaccine queue. If dose-stretching cuts the time to be vaccinated in half, for example, then that may mean cutting the time to be vaccinated from two months to one month in a developed country but cutting it from two years to one year in a country that is currently at the back of the queue.