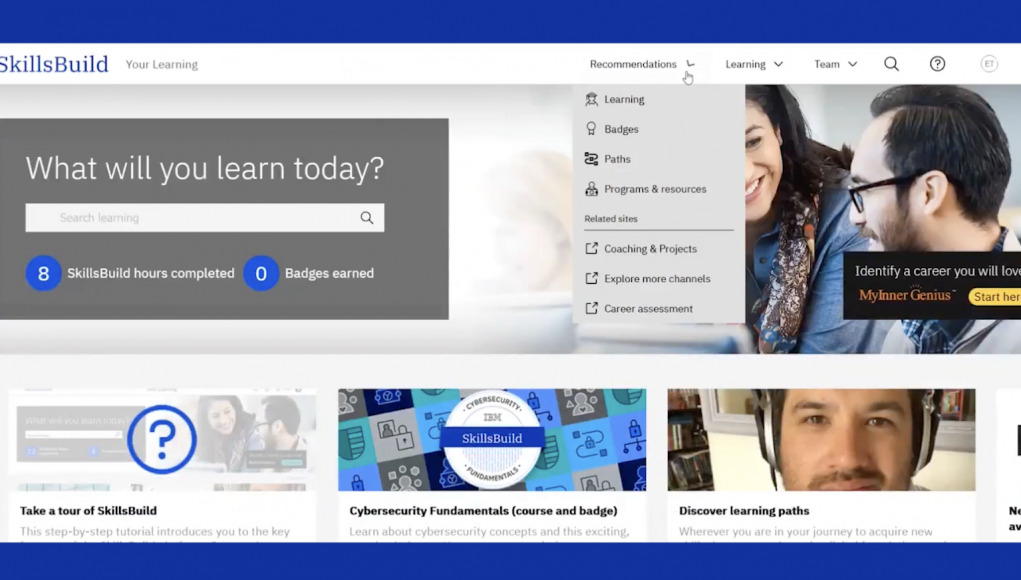

Digital wallets for verifiable credentials

Purdue University had something like this almost a decade ago, but there’s even more call for this kind of thing now, post-pandemic and in a Verifiable Credentials landscape.

Everyone’s addicted to marrying ‘skills’ with ‘jobs’ but I think there’s definitely an Open Recognition aspect to all of this.

ASU Pocket captures students’ traditional and non-traditional educational credentials, which are now, with the emergence of verifiable credentials, more portable than ever before. This gives students the autonomy to securely own, control and share their holistic evidence of learning with employers.Source: ASU Pocket: A digital wallet to capture learners’ real-time achievementsA digital wallet, like ASU Pocket, holds verifiable credentials – which are digital representations of real-world credentials like government-issued IDs, passports, driver’s licenses, birth certificates, educational degrees, professional certifications, awards, and so on. In the past, these credentials have been stored in physical form, making them susceptible to fraud and loss. However, with advances in technology, these credentials can be stored electronically, using cryptographic techniques to ensure their authenticity. This makes it possible to verify the credential without revealing sensitive information, such as a social security number.

[…]

At ASU Pocket, we also view verifiable credentials as an important tool for social impact. They provide a way for people to document their skills and accomplishments, which can be used to gain new opportunities. For example, someone with a verifiable skill credential for customer service might be able to use it to get a job in a call center. Likewise, someone with a verifiable credential for computer programming might be able to use it to get a job as a software developer.

In both cases, the verifiable credential provides a way for the individual to demonstrate their skills and qualifications gained through or outside of traditional learning pathways. This is especially impactful for marginalized groups who may have difficulty obtaining traditional credentials, such as degrees or certifications.

Skills-based hiring vs universities

This is Stephen Downes' commentary on an article by Tom Vander Ark. I think crunch time is coming for universities, especially when you think about how people are increasingly applying for jobs with portfolios, microcredentials, and proof of experience, rather than simply a CV with a degree on it.

Educators need to be aware that the marketing campaign against their unique value proposition is well underway. "Companies are missing out on skilled, diverse talent when they arbitrarily ‘require’ a four-year degree. It’s bad for workers and it’s bad for business. It doesn’t have to be this way," says former McKinsey partner Byron Auguste, who founded Opportunity@Work. "Instead of ‘screening out’ by pedigree, smart employers are increasing ‘screening in talent for performance and potential." The question for colleges and universities is this: if people no longer value your degrees and certificates, what will you be selling them when you charge them tuition fees?Source: The Rise of Skills-Based Hiring And What it Means for Education | Stephen Downes

Peer review sucks

I don’t have much experience of peer review (I’ve only ever submitted one article and peer reviewed two) but it felt a bit archaic at the time. From what I hear from others, they feel the same.

The interesting thing from my perspective is that the whole edifice of the university system is slowly crumbling. Academics know that the system is ridiculous.

This then is why I was so bothered about how Covid-19 research is reported: peer review is no guard, is no gold standard, has little role beyond gate-keeping. It is noisy, biased, fickle. So pointing out that some piece of research has not been peer reviewed is meaningless: peer review has played no role in deciding what research was meaningful in the deep history of science; and played little role in deciding what research was meaningful in the ongoing story of Covid-19. The mere fact that news stories were written about the research decided it was meaningful: because it needed to be done. Viral genomes needed sequencing; vaccines needed developing; epidemiological models needed simulating. The reporting of Covid-19 research has shown us just how badly peer review needs peer reviewing. But, hey, you’ll have to take my word for it because, sorry, this essay is (not yet peer reviewed).Source: The Absurdity of Peer Review | Elemental

Seeing through is rarely seeing into

♂️ What does it mean to be a man in 2020? Introducing our news series on masculinity

✏️ Your writing style is costly (Or, a case for using punctuation in Slack)

Quotation-as-title by Elizabeth Bransco. Image from top-linked post.

Gatekeepers of opportunity and the lottery of privilege

Despite starting out as a pejorative term, 'meritocracy' is something that, until recently, few people seem to have had a problem with. One of the best explanations of why meritocracy is a problematic idea is in this Mozilla article from a couple of years ago. Basically, it ascribes agency to those who were given opportunities due to pre-existing privilege.

In an interview with The Chronicle of Higher Education, Michael Sandel makes some very good points about the American university system, which can be more broadly applied to other western nations, such as the UK, which have elite universities.

The meritocratic hubris of elites is the conviction by those who land on top that their success is their own doing, that they have risen through a fair competition, that they therefore deserve the material benefits that the market showers upon their talents. Meritocratic hubris is the tendency of the successful to inhale too deeply of their success, to forget the luck and good fortune that helped them on their way. It goes along with the tendency to look down on those less fortunate, and less credentialed, than themselves. That gives rise to the sense of humiliation and resentment of those who are left out.

Michael Sandel, quoted in 'The Insufferable Hubris of the Well-Credentialed'

As someone who is reasonably well-credentialed, I nevertheless see a fundamental problem with requiring a degree as an 'entry-level' qualification. That's why I first got interested in Open Badges nearly a decade ago.

Despite the best efforts of the community, elite universities have a vested in maintaining the status quo. Eventually, the whole edifice will come crashing down, but right now, those universities are the gatekeepers to opportunity.

Society as a whole has made a four-year university degree a necessary condition for dignified work and a decent life. This is a mistake. Those of us in higher education can easily forget that most Americans do not have a four-year college degree. Nearly two-thirds do not.

[...]

We also need to reconsider the steep hierarchy of prestige that we have created between four-year colleges and universities, especially brand-name ones, and other institutions of learning. This hierarchy of prestige both reflects and exacerbates the tendency at the top to denigrate or depreciate the contributions to the economy made by people whose work does not depend on having a university diploma.

So the role that universities have been assigned, sitting astride the gateway of opportunity and success, is not good for those who have been left behind. But I’m not sure it’s good for elite universities themselves, either.

MICHAEL SANDEL, QUOTED IN 'THE INSUFFERABLE HUBRIS OF THE WELL-CREDENTIALED'

Thankfully, Sandel, has a rather delicious solution to decouple privilege from admission to elite universities. It's not a panacea, but I like it a first step.

What might we do about it? I make a proposal in the book that may get me in a lot of trouble in my neighborhood. Part of the problem is that having survived this high-pressured meritocratic gauntlet, it’s almost impossible for the students who win admission not to believe that they achieved their admission as a result of their own strenuous efforts. One can hardly blame them. So I think we should gently invite students to challenge this idea. I propose that colleges and universities that have far more applicants than they have places should consider what I call a “lottery of the qualified.” Over 40,000 students apply to Stanford and to Harvard for about 2,000 places. The admissions officers tell us that the majority are well-qualified. Among those, fill the first-year class through a lottery. My hunch is that the quality of discussion in our classes would in no way be impaired.

The main reason for doing this is to emphasize to students and their parents the role of luck in admission, and more broadly in success. It’s not introducing luck where it doesn’t already exist. To the contrary, there’s an enormous amount of luck in the present system. The lottery would highlight what is already the case.

MICHAEL SANDEL, QUOTED IN 'THE INSUFFERABLE HUBRIS OF THE WELL-CREDENTIALED'

Would people like me be worse off in a more egalitarian system? Probably. But that's kind of the point.

Face-to-face university classes during a pandemic? Why?

Earlier in my career, when I worked for Jisc, I was based at Northumbria University in Newcastle. It's just been announced that 770 students there have been infected with COVID-19.

As Lorna Finlayson, a philosophy lecturer at the University of Essex, points out, the desire to get students on campus for face-to-face teaching is driven by economics. Universities are businesses, and some of them are likely to fail this academic year.

[A]fter years of pushing to expand online learning and “lecture capture” on the basis that it is what students want, university managers have decided that what students really want now, during a global pandemic, is face-to-face contact. This sudden-onset fetish reached its most perverse extreme in the case of Boston University, which, realising that many teaching rooms lack good ventilation or even windows, decided to order “giant air circulators”, only to discover that the air circulators were very noisy. Apparently unable to source enough “mufflers” for the air circulators, the university ordered Bluetooth headsets to enable students and teachers to communicate over the roar of machinery.

All of which raises the question: why? The determination to bring students back to campus at any cost doesn’t stem from a dewy-eyed appreciation of in-person pedagogy, nor from concerns about the impact of isolation on students’ mental health. If university managers had any interest in such things, they would not have spent years cutting back on study skills support and counselling services.

Lorna Finlayson, How universities tricked students into returning to campus (The Guardian)

I know people who work in universities in various positions. What they tell me astounds me; a callous disregard for human life in the pursuit of either economic survival, or profit.

This is, as usual, all about the money. With student fees and rents now their main source of revenue, universities will do anything to recruit and retain. When the pandemic hit, university managers warned of a potentially catastrophic loss of income from international student fees in particular. Many used this as an excuse to cut jobs and freeze pay, even as vice-chancellors and senior management continued to rake in huge salaries. As it turned out, international student admissions reached a record high this year, with domestic undergraduate numbers also up – perhaps less due to the irresistibility of universities’ “offer” than to the lack of other options (needless to say, staff jobs and pay have yet to be reinstated).

Lorna Finlayson, How universities tricked students into returning to campus (The Guardian)

But students are more than just fee-payers. They are rent-payers too. Rightly or wrongly, most of those in charge of universities have assumed that only the promise of face-to-face classes would tempt students back to their accommodation. That promise can be safely broken only once rental contracts are signed and income streams flowing.

I predict legal action at some point in the near future.

Friday filchings

I'm having to write this ahead of time due to travel commitments. Still, there's the usual mixed bag of content in here, everything from digital credentials through to survival, with a bit of panpsychism thrown in for good measure.

Did any of these resonate with you? Let me know!

Competency Badges: the tail wagging the dog?

Recognition is from a certain point of view hyperlocal, and it is this hyperlocality that gives it its global value – not the other way around. The space of recognition is the community in which the competency is developed and activated. The recognition of a practitioner in a community is not reduced to those generally considered to belong to a “community of practice”, but to the intersection of multiple communities and practices, starting with the clients of these practices: the community of practice of chefs does not exist independently of the communities of their suppliers and clients. There is also a very strong link between individual recognition and that of the community to which the person is identified: shady notaries and politicians can bring discredit on an entire community.

Serge Ravet

As this roundup goes live I'll be at Open Belgium, and I'm looking forward to catching up with Serge while I'm there! My take on the points that he's making in this (long) post is actually what I'm talking about at the event: open initiatives need open organisations.

Universities do not exist ‘to produce students who are useful’, President says

Mr Higgins, who was opening a celebration of Trinity College Dublin’s College Historical Debating Society, said “universities are not there merely to produce students who are useful”.

“They are there to produce citizens who are respectful of the rights of others to participate and also to be able to participate fully, drawing on a wide range of scholarship,” he said on Monday night.

The President said there is a growing cohort of people who are alienated and “who feel they have lost their attachment to society and decision making”.

Jack Horgan-Jones (The Irish Times)

As a Philosophy graduate, I wholeheartedly agree with this, and also with his assessment of how people are obsessed with 'markets'.

Perennial philosophy

Not everyone will accept this sort of inclusivism. Some will insist on a stark choice between Jesus or hell, the Quran or hell. In some ways, overcertain exclusivism is a much better marketing strategy than sympathetic inclusivism. But if just some of the world’s population opened their minds to the wisdom of other religions, without having to leave their own faith, the world would be a better, more peaceful place. Like Aldous Huxley, I still believe in the possibility of growing spiritual convergence between different religions and philosophies, even if right now the tide seems to be going the other way.

Jules Evans (Aeon)

This is an interesting article about the philosophy of Aldous Huxley, whose books have always fascinated me. For some reason, I hadn't twigged that he was related to Thomas Henry Huxley (aka "Darwin's bulldog").

What the Death of iTunes Says About Our Digital Habits

So what really failed, maybe, wasn’t iTunes at all—it was the implicit promise of Gmail-style computing. The explosion of cloud storage and the invention of smartphones both arrived at roughly the same time, and they both subverted the idea that we should organize our computer. What they offered in its place was a vision of ease and readiness. What the idealized iPhone user and the idealized Gmail user shared was a perfect executive-functioning system: Every time they picked up their phone or opened their web browser, they knew exactly what they wanted to do, got it done with a calm single-mindedness, and then closed their device. This dream illuminated Inbox Zero and Kinfolk and minimalist writing apps. It didn’t work. What we got instead was Inbox Infinity and the algorithmic timeline. Each of us became a wanderer in a sea of content. Each of us adopted the tacit—but still shameful—assumption that we are just treading water, that the clock is always running, and that the work will never end.

Robinson Meyer (The Atlantic)

This is curiously-written (and well-written) piece, in the form of an ordered list, that takes you through the changes since iTunes launched. It's hard to disagree with the author's arguments.

Imagine a world without YouTube

But what if YouTube had failed? Would we have missed out on decades of cultural phenomena and innovative ideas? Would we have avoided a wave of dystopian propaganda and misinformation? Or would the internet have simply spiraled into new — yet strangely familiar — shapes, with their own joys and disasters?

Adi Robertson (The Verge)

I love this approach of imagining how the world would have been different had YouTube not been the massive success it's been over the last 15 years. Food for thought.

Big Tech Is Testing You

It’s tempting to look for laws of people the way we look for the laws of gravity. But science is hard, people are complex, and generalizing can be problematic. Although experiments might be the ultimate truthtellers, they can also lead us astray in surprising ways.

Hannah Fry (The New Yorker)

A balanced look at the way that companies, especially those we classify as 'Big Tech' tend to experiment for the purposes of engagement and, ultimately, profit. Definitely worth a read.

Trust people, not companies

The trend to tap into is the changing nature of trust. One of the biggest social trends of our time is the loss of faith in institutions and previously trusted authorities. People no longer trust the Government to tell them the truth. Banks are less trusted than ever since the Financial Crisis. The mainstream media can no longer be trusted by many. Fake news. The anti-vac movement. At the same time, we have a generation of people who are looking to their peers for information.

Lawrence Lundy (Outlier Ventures)

This post is making the case for blockchain-based technologies. But the wider point is a better one, that we should trust people rather than companies.

The Forest Spirits of Today Are Computers

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature. Agriculture de-wilded the meadows and the forests, so that even a seemingly pristine landscape can be a heavily processed environment. Manufactured products have become thoroughly mixed in with natural structures. Now, our machines are becoming so lifelike we can’t tell the difference. Each stage of technological development adds layers of abstraction between us and the physical world. Few people experience nature red in tooth and claw, or would want to. So, although the world of basic physics may always remain mindless, we do not live in that world. We live in the world of those abstractions.

George Musser (Nautilus)

This article, about artificial 'panpsychism' is really challenging to the reader's initial assumptions (well, mine at least) and really makes you think.

The man who refused to freeze to death

It would appear that our brains are much better at coping in the cold than dealing with being too hot. This is because our bodies’ survival strategies centre around keeping our vital organs running at the expense of less essential body parts. The most essential of all, of course, is our brain. By the time that Shatayeva and her fellow climbers were experiencing cognitive issues, they were probably already experiencing other organ failures elsewhere in their bodies.

William Park (BBC Future)

Not just one story in this article, but several with fascinating links and information.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Header image by Tim Mossholder.