- Reinforcement of the connection between productivity and human value

- Creation of 'bullshit jobs'

- Could deny people chance to engage in other pursuits (if poorly implemented)

- Potential to leave behind prior who cannot work (disability / other health concerns)

- Seems didactic and disciplinary

Saturday sandcastles

The photos of brutalist sandcastles accompanying this week's link roundup made me both smile and really miss care-free walks on the beach. Although technically we're still allowed to visit the coast, our local council has closed nearby car parks.

This week I've been busy, busy, but managed to squeeze in a bit of non-fiction reading, the best of which I'm sharing below. Oh, and one link that I can' really quote is UnblockIt which was shared via our team chat this week. If your ISP filters certain sites, you might want to bookmark it...

There will be no 'back to normal'

In this article, we summarise and synthesise various - often opposing - views about how the world might change. Clearly, these are speculative; no-one knows what the future will look like. But we do know that crises invariably prompt deep and unexpected shifts, so that those anticipating a return to pre-pandemic normality may be shocked to find that many of the previous systems, structures, norms and jobs have disappeared and will not return.

Nesta

I'm going to return to this article time and again, as it breaks down in a really helpful way what's likely to happen post-pandemic in the following areas: political, economic, sociocultural, technological, legal, and environmental.

Plan for 5 years of lockdown

I’m attempting to be pragmatic. I think this is one of those times where we should hope for the best but plan for the worst. Crucially, I think that a terrifying number of people are in denial about the timescales of disruption that Covid-19 will cause, and this is causing them to make horrible personal and professional decisions. I believe that we have a responsibility to consider any reasonably likely worst case scenario, and take appropriate steps to mitigate it. But to do that we have to be honest about the worst case.

Patrick Gleeson

It's hard to disagree with the points made in this post, especially as the scenario planning that universities are doing seems to point in the same direction. Having said that, I don't think 'lockdown' will mean the same thing everywhere and at each stage of the pandemic.

'Will coronavirus change our attitudes to death? Quite the opposite'

For centuries, people used religion as a defence mechanism, believing that they would exist for ever in the afterlife. Now people sometimes switch to using science as an alternative defence mechanism, believing that doctors will always save them, and that they will live for ever in their apartment. We need a balanced approach here. We should trust science to deal with epidemics, but we should still shoulder the burden of dealing with our individual mortality and transience.

The present crisis might indeed make many individuals more aware of the impermanent nature of human life and human achievements. Nevertheless, our modern civilisation as a whole will most probably go in the opposite direction. Reminded of its fragility, it will react by building stronger defences. When the present crisis is over, I don’t expect we will see a significant increase in the budgets of philosophy departments. But I bet we will see a massive increase in the budgets of medical schools and healthcare systems.

Yuval Noah Harari

Some amazing writing, as ever, by Harari, who argues that, because our secular societies focus on the here and now rather than the afterlife, science has almost become a religion.

A startup debt to talk about more: emotional debt

We incur emotional debt whenever there’s an experience we’ve had, but not fully digested in all aspects of it. In my trauma therapy training I learned that this is in fact a natural and important human survival skill. Imagine you’re living in a pre-historic village and it gets raided by a neighboring tribe. Although no one gets killed, a number of houses have been burned down and food has been stolen. The next morning the most important tasks for everyone are to protect the village again, rebuild the houses and hunt for food to survive. Many of the villagers will have been deeply traumatized from the fears and terror they experienced in their bodies. Since food and shelter takes first priority to humans, not processing these emotions for now is a debt that’s necessary and important to incur. We can put it aside and leave it stuck in our bodies, ready to reengage and digest it later. It’s a great survival feature if you will.

A couple of weeks later when everything has been rebuilt, there might be a chance for the local shaman to offer a ritual around the fireplace where everyone can gather and re-experience the emotions that were too difficult to deal with at the actual event of the raid: the rage and anger towards the attackers, the fear and the terror over their lives and eventually the grief for the loss of their goods and most importantly their safety. Once that has been felt and integrated, everyone is able to move on and the night of the village raid can safely go into the history books, fairy tales and heroes journey accounts that luckily everyone survived, yet learned from.

Leo Widrich

While this is framed in terms of startups, I think every organisation has 'emotional debt' that they have to deal with. I like this framing, and will be using it from now on to explain why teams need times of compression and decompression (instead of never-ending 'sprints').

Don’t let remote leadership bring out the worst in you

Recognize that the pressure you apply is a reaction to a construct of control. You think you can control people – and things – and the reality is you can’t. The quicker you can realize this, the sooner you can shift to a frame of mind where you can focus constructively on the things that actually help your team, such as: (1) Making it clear why the work matters (2) Creating milestones to help that person achieve that work (3) Giving as much context as possible so they can make the best decisions (4) Helping them think through tough problems they encounter.

Claire Lew

I've led a remote team for a couple of years now, and worked remotely for six years before that. Despite this, it's easy to fall into bad habits, so this is a useful article to remind all leaders (most of whom are remote now!) that the amount of time someone spends on something does not equate to progress made.

Google Apple Contact Tracing (GACT): a wolf in sheep’s clothes.

But the bigger picture is this: it creates a platform for contact tracing that works all across the globe for most modern smart phones (Android Marshmallow and up, and iOS 13 capable devices) across both OS platforms. Unless appropriate safeguards are in place (including, but not limited to, the design of the system as described above – we will discuss this more below) this would create a global mass-surveillance system that would reliably track who has been in contact with whom, at what time and for how long. (And where, if GPS is used to record the location.) GACT works much more reliably and extensively than any other system based on either GPS or mobile phone location data (based on cell towers) would be able to (under normal conditions). I want to stress this point because some people have responded to this threat saying that this is something companies like Google (using their GPS and WiFi names based location history tool) can already do for years. This is not the case. This type of contact tracing really brings it to another level.

Jaap-Henk Hoepman

This, by a professor in the Netherlands who focuses on 'privacy by design' is why I'm really concerned about the Google/Apple Contact Tracing (GACT) programme. It's only likely to be of marginal help in fighting the virus, but sets up a global surveillance network for decades to come.

In this Zombie Apocalypse, your Homework is due at 5pm

Year in and year out, when school’s in, children know that they are to be at certain places at certain times, doing particular tasks in particular ways. And now, weeks loom ahead where they are faced with many of the same tasks, absent of all the pomp and circumstance. This is the ultimate zombie apocalypse nightmare—a pandemic has hit the world with a mighty force, schools and tuition centers are shut, and homework is still due. Children are adaptable creatures, but it will be challenging for many, if not most, to do all that they are expected to do under these altered conditions.

Youyenn Teo

I was attracted to this article by its great title, but it's actually an interesting insight into both education in a Singaporean context and the gendered nature of care in our societies.

Free Money for Surfers: A Genealogy of the Idea of Universal Basic Income

As cash transfers are increasingly seen as the ideal way to confront the magnitude of the coronavirus threat, it is unclear whether our political imagination is truly up to the task. The current crisis might accelerate rather than decrease our dependency on the market, strengthening capital’s grip on society. Large-scale public works are evidently unfeasible with physical distancing. But, with a clear medical equipment shortage and lacking trained personnel, there is obvious space for public planning responses, and “production for use value” seems ever more necessary. None of these ills will be solved by cash transfers.

Anton Jäger & Daniel Zamora

This, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, considers a new work by Peter Sloman entitled The Idea of a Guaranteed Income and the Politics of Redistribution in Modern Britain. Having previously been cautiously optimistic about Universal Basic Income (or 'cash transfers') I'm not so sure it would all work out so well. I'd rather we funded things like the NHS, but then that might be my white male privilege speaking.

How we made the Keep Calm and Carry On poster

I first found the poster in 2000, folded up at the bottom of a box of books we had bought at an auction. I liked it straight away and showed it to my wife Mary – she had it framed and put up in the shop. The next thing we found was that customers wanted to buy it. I suggested we make copies but Mary said: “No, it’ll spoil the purity.” She went away for a week’s holiday, so I secretly got 500 copies made.

Stuart Manley (interviewed by malcolm jack)

This ridiculously-famous poster was discovered in a wonderful second-hand bookshop not too far away from us, and which we visit several times per year. I love the story behind it.

Images via The Guardian: For one tide only: modernist sandcastles – in pictures

We have it in our power to begin the world over again

UBI, GDP, and Libertarian Municipalism

It's sobering to think that, in years to come, historians will probably refer to the 75 years between the end of the Second World War and the start of this period we've just begun with a single name.

Whatever we end up calling it, one thing is for sure: what comes next can't be a continuation of what went before. We need a sharp division of life pre- and post-pandemic.

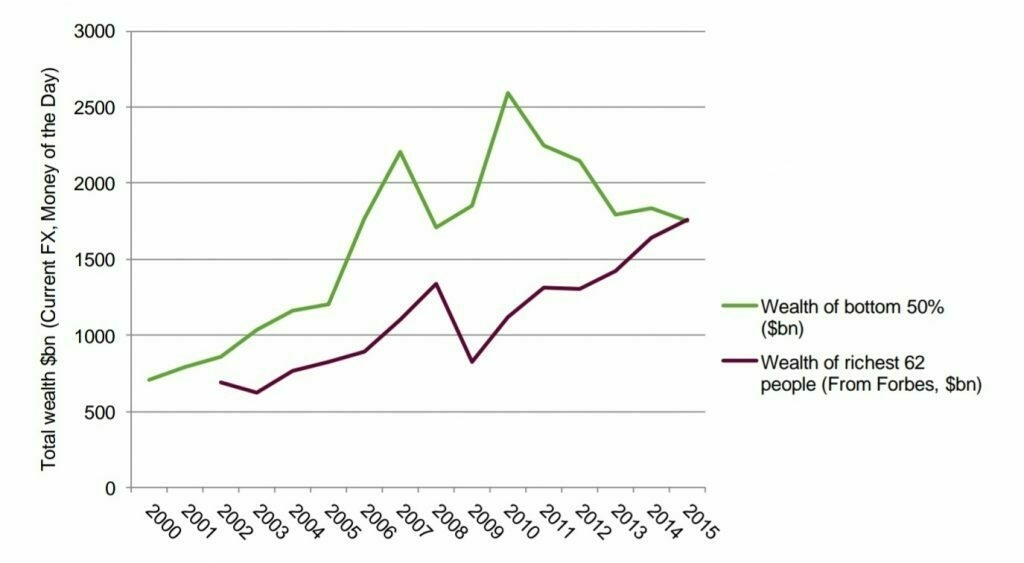

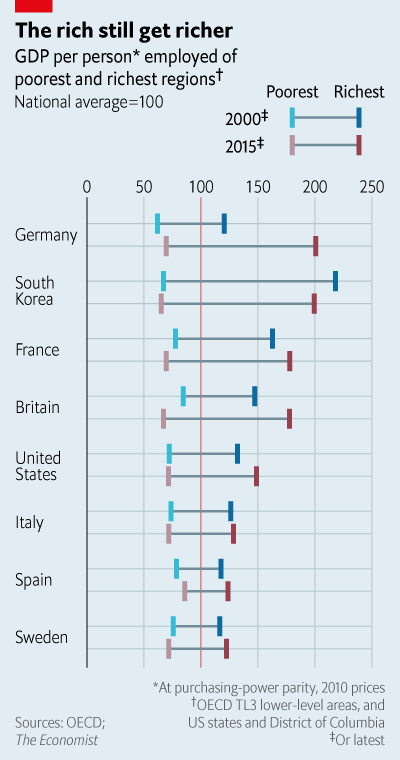

That's because our societies have been increasingly unequal since 2008, when the global financial crisis meant that the rich consolidated their position while the rest of us paid for the mistakes of bankers and the global elite.

So what can we do about this? What should we be demanding once we're allowed back out of our houses? What should we organise against?

I've been a proponent of Universal Basic Income over the last few years, but, I have to say that the closer it comes to being a reality, the more concerns I have about its implementation. Even if it's brought in by a left-leaning government, there's still the danger that it's subsequently used as a weapon against the poor by a new adminstration.

That's why I was interested in this section from a book I'm reading at the moment. Writing in Future Histories, Lizzie O'Shea suggests that we need to think beyond UBI to include other approaches:

Alongside this, we need to consider how productive, waged work could be more democratically organized to meet the needs of society rather than individual companies. To this end, one commonly suggested alternative to a basic income is a job guarantee. The idea is that the government offers a job to anyone who wants one and is able to work, in exchange for a minimum wage. Jobs could be created around infrastructure projects, for example, or care work. Government spending on this enlarged public sector world act like a kind of Keynesian expenditure, to stimulate the economy and buffer the population against the volatility of the private labor market. Modeling suggests that this would be more cost-effective than a basic income (often critiqued for being too expensive) and avoid many of the inflationary perils that might accompany basic income proposals. It could also be used to jump-start sections of the economy that are politically important, like green energy, carbon reduction and infrastructure. A job guarantee could help us collectively decide what kind of work is must urgent and necessary and to prioritize that through democratically accountable representatives.

Lizzie O'Shea, Future Histories

Of course, as she points out, there are a number of drawbacks to a job guarantee scheme:

Nevertheless, O'Shea believes that a combination of a job guarantee, UBI, and government-provided services is the way forward:

Ultimately, we need a combination of these programs. We need the liberty offered by a basic income, the sustainability promised by the organization of a job guarantee, and the protection of dignity offered by centrally planned essential services. It is like a New Deal for the age of automation, a ground rent for the digital revolution, in which the benefits of accelerated productive capacity are shared among everyone. From each according to his ability, to each according to their need - a twenty-first-century vision of socialism. "We have it in our power to begin the world over again," wrote Thomas Paine in an appendix to Common Sense, just before one of the most revolutionary periods in human history. We have a similar opportunity today.

Lizzie O'Shea, Future Histories

While I don't disagree that we will continue to need "the protection of dignity offered by centrally planned essential services," I'm not so sure that giving the state so much power over our lives is a good thing. I think this approach papers over the cracks of neoliberalism, giving billionaires and capitalists a get-out-of-jail-free card.

Instead, I'd like to see a post-pandemic breakup of mega corporations. While a de jure limit on how much one individual or one organisation can be worth is likely to be unworkable, there's ways we can make de facto limits on this a reality.

People respond to incentives, including how easy or hard it is to do something. I know from experience how easy it is to set up a straightforward limited company in the UK and how difficult it is to set up a co-operative. To get to where we need to be, we need to ensure collective decision-making is the norm within organisations owned by workers. And then these worker-owned organisations need to co-ordinate for the good of everyone.

I'm a huge believer in decentralisation, not just technologically but politically and socially; we don't need governments, billionaires, or celebrities telling us what to do with our lives. We need to think wider and deeper. My current thinking aligns with this section on libertarian municipalism from the Wikipedia page on the political philosopher Murray Bookchin:

Libertarian Municipalism constitutes the politics of social ecology, a revolutionary effort in which freedom is given institutional form in public assemblies that become decision-making bodies.

Wikipedia

...or, in other words:

The overriding problem is to change the structure of society so that people gain power. The best arena to do that is the municipality—the city, town, and village—where we have an opportunity to create a face-to-face democracy.

Wikipedia

Some people think that, in these days of super-fast connections to anyone on the planet, that nation states are dead, and that we should be building communities on the blockchain. I have yet to see a proposal of how this would be workable in practice; everything I've seen so far extrapolates naïvely from what's technically possible to what should be socially desirable.

Yes, we can and should have solidarity with people around the world with whom we work and socialise. But this does not negate the importance of decision-making at a local level. Gaming clans don't yet do bin collections, and colleagues in a different country can't fix the corruption riddling your local government.

Ultimately, then, we're going to need a whole new politics and social contract after the pandemic. I sincerely hope we manage to grasp the nettle and do something radically different. I'm not sure how we'll all survive if the rich, once again, come out of all this even richer than before.

BONUS: check out this 1978 speech from Murray Bookchin where he calls for utopia, not futurism.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup, become a supporter, or download Thought Shrapnel Vol.1: Personal Productivity!

Quotation-as-title from Thomas Paine. Header image by Stas Knop.