- Is the approach narrowly tailored or a categorical ban?

- Does it empower users?

- Is it transparent?

- Is the policy consistent with human rights principles?

- Am I working on something that inspires me (and others)?

- Am I working on something with a significant impact?

- Am I working in a way that makes getting where I want to go as easy as possible (and keeps me there as long as possible)?

- Renata Ávila: “The Internet of creation disappeared. Now we have the Internet of surveillance and control” (CCCB Lab) — "This lawyer and activist talks with a global perspective about the movements that the power of “digital colonialism” is weaving. Her arguments are essential for preventing ourselves from being crushed by the technological world, from being carried away by the current of ephemeral divertemento. For being fully aware that, as individuals, our battle is not lost, but that we can control the use of our data, refuse to give away our facial recognition or demand that the privacy laws that protect us are obeyed."

- Everything Is Private Equity Now (Bloomberg) — "The basic idea is a little like house flipping: Take over a company that’s relatively cheap and spruce it up to make it more attractive to other buyers so you can sell it at a profit in a few years. The target might be a struggling public company or a small private business that can be combined—or “rolled up”—with others in the same industry."

- Forget STEM, We Need MESH (Our Human Family) — "I would suggest a renewed focus on MESH education, which stands for Media Literacy, Ethics, Sociology, and History. Because if these are not given equal attention, we could end up with incredibly bright and technically proficient people who lack all capacity for democratic citizenship."

- Connecting the curious (Harold Jarche) — "If we want to change the world, be curious. If we want to make the world a better place, promote curiosity in all aspects of learning and work. There are still a good number of curious people of all ages working in creative spaces or building communities around common interests. We need to connect them."

- Twitter: No, really, we're very sorry we sold your security info for a boatload of cash (The Register) — "The social networking giant on Tuesday admitted to an "error" that let advertisers have access to the private information customers had given Twitter in order to place additional security protections on their accounts."

- Digital tools interrupt workers 14 times a day (CIO Dive) — "The constant chime of digital workplace tools including email, instant messaging or collaboration software interrupts knowledge workers 13.9 times on an average day, according to a survey of 3,750 global workers from Workfront."

- Book review – Curriculum: Athena versus the Machine (TES) — "Despite the hope that the book is a cure for our educational malaise, Curriculum is a morbid symptom of the current political and intellectual climate in English education."

- Fight for the planet: Building an open platform and open culture at Greenpeace (Opensource.com) — "Being as open as we can, pushing the boundaries of what it means to work openly, doesn't just impact our work. It impacts our identity."

- Psychodata (Code Acts in Education) — "Social-emotional learning sounds like a progressive, child-centred agenda, but behind the scenes it’s primarily concerned with new forms of child measurement."

- “Things that were considered worthless are redeemed” (Ira David Socol) — "Empathy plus Making must be what education right now is about. We are at both a point of learning crisis and a point of moral crisis. We see today what happens — in the US, in the UK, in Brasil — when empathy is lost — and it is a frightening sight. We see today what happens — in graduates from our schools who do not know how to navigate their world — when the learning in our schools is irrelevant in content and/or delivery."

- Voice assistants are going to make our work lives better—and noisier (Quartz) — "Active noise cancellation and AI-powered sound settings could help to tackle these issues head on (or ear on). As the AI in noise cancellation headphones becomes better and better, we’ll potentially be able to enhance additional layers of desirable audio, while blocking out sounds that distract. Audio will adapt contextually, and we’ll be empowered to fully manage and control our soundscapes.

- We Aren’t Here to Learn What We Already Know (LA Review of Books) — "A good question, in short, is an honest question, one that, like good theory, dances on the edge of what is knowable, what it is possible to speculate on, what is available to our immediate grasp of what we are reading, or what it is possible to say. A good question, that is, like good theory, might be quite unlovely to read, particularly in its earliest iterations. And sometimes it fails or has to be abandoned."

- The runner who makes elaborate artwork with his feet and a map (The Guardian) — "The tracking process is high-tech, but the whole thing starts with just a pen and paper. “When I was a kid everyone thought I’d be an artist when I grew up – I was always drawing things,” he said. He was a particular fan of the Etch-a-Sketch, which has something in common with his current work: both require creating images in an unbroken line."

- What I Do When it Feels Like My Work Isn’t Good Enough (James Clear) — "Release the desire to define yourself as good or bad. Release the attachment to any individual outcome. If you haven't reached a particular point yet, there is no need to judge yourself because of it. You can't make time go faster and you can't change the number of repetitions you have put in before today. The only thing you can control is the next repetition."

- Online porn and our kids: It’s time for an uncomfortable conversation (The Irish Times) — "Now when we talk about sex, we need to talk about porn, respect, consent, sexuality, body image and boundaries. We don’t need to terrify them into believing watching porn will ruin their lives, destroy their relationships and warp their libidos, maybe, but we do need to talk about it."

- Drones will fly for days with new photovoltaic engine (Tech Xplore) — "[T]his finding builds on work... published in 2011, which found that the key to boosting solar cell efficiency was not by absorbing more photons (light) but emitting them. By adding a highly reflective mirror on the back of a photovoltaic cell, they broke efficiency records at the time and have continued to do so with subsequent research.

- Twitter won’t ruin the world. But constraining democracy would (The Guardian) — "The problems of Twitter mobs and fake news are real. As are the issues raised by populism and anti-migrant hostility. But neither in technology nor in society will we solve any problem by beginning with the thought: “Oh no, we put power into the hands of people.” Retweeting won’t ruin the world. Constraining democracy may well do.

- The Encryption Debate Is Over - Dead At The Hands Of Facebook (Forbes) — "Facebook’s model entirely bypasses the encryption debate by globalizing the current practice of compromising devices by building those encryption bypasses directly into the communications clients themselves and deploying what amounts to machine-based wiretaps to billions of users at once."

- Living in surplus (Seth Godin) — "When you live in surplus, you can choose to produce because of generosity and wonder, not because you’re drowning."

- Find the best aggregators

- Get summaries

- Cut the redundancy!

- Unsubscribe to as many things as possible

- Recognise that gossip and celebrity entertainment are black holes

- Pick the categories you want for a balanced perspective, and include some from OUTSIDE your main field of interest

- Be a LOT more realistic about what you're likely to get to, and throw the rest out.

- In any thing you need to learn, find a person who can tell you what is:

- Need to know

- Should know

- Nice to know

- Edge case, only if it applies to you specifically

- Useless

- List all of the perceived benefits

- List all of the perceived drawbacks

- List all of the ways that the people making the free app can make money

- The secret rules of the internet (The Verge) — "The moderators of these platforms — perched uneasily at the intersection of corporate profits, social responsibility, and human rights — have a powerful impact on free speech, government dissent, the shaping of social norms, user safety, and the meaning of privacy. What flagged content should be removed? Who decides what stays and why? What constitutes newsworthiness? Threat? Harm? When should law enforcement be involved?"

- The New Wilderness (Idle Words) — "Ambient privacy is not a property of people, or of their data, but of the world around us. Just like you can’t drop out of the oil economy by refusing to drive a car, you can’t opt out of the surveillance economy by forswearing technology (and for many people, that choice is not an option). While there may be worthy reasons to take your life off the grid, the infrastructure will go up around you whether you use it or not."

- IQ rates are dropping in many developed countries and that doesn't bode well for humanity (Think) — "Details vary from study to study and from place to place given the available data. IQ shortfalls in Norway and Denmark appear in longstanding tests of military conscripts, whereas information about France is based on a smaller sample and a different test. But the broad pattern has become clearer: Beginning around the turn of the 21st century, many of the most economically advanced nations began experiencing some kind of decline in IQ."

- Global attention span is narrowing and trends don't last as long, study reveals (The Guardian) — "The empirical data found periods where topics would sharply capture widespread attention and promptly lose it just as quickly."

- Existence precedes likes: how online behaviour defines us (Aeon) — "Something strange is happening as our lives migrate from the analogue to the digital."

- Emotional Intelligence: The Social Skills You Weren't Taught in School (Lifehacker) — "People who exhibit emotional intelligence have the less obvious skills necessary to get ahead in life, such as managing conflict resolution, reading and responding to the needs of others, and keeping their own emotions from overflowing and disrupting their lives."

Taste ripens at the expense of happiness

🧐 Habits, Data, and Things That Go Bump in the Night: Microsoft for Education — "Microsoft’s ubiquity, however, is sometimes mistaken for banality. Because it is everywhere, because we have all used it forever, we assume we can trust it."

I haven't voluntarily used something made by Microsoft (as opposed to acquired by it) for... about 20 years?

⏳ You Can Set Screen-Time Rules That Don’t Ruin Your Kids’ Lives — "Bear in mind that the limits you set need not be a specific number of minutes. Try to think of other, more natural ways of breaking up their activities. Maybe your kids play one game before tackling homework. Also, consider granting them one day per weekend with fewer restrictions on screen-time socializing. Giving them more autonomy over their weekends helps approximate the fun and flexibility of their pre-COVID world, and lets them unwind and hang out more with their friends."

This has been really hard to managed as a parent, and it's easy to think that you're always doing it wrong.

💬 Why do we keep on telling others what to do? — "Usually starting a conversation out with telling people what you feel they are doing wrong is going to make it a negative conversation all in all, and I tend to believe that it's better to follow “the campfire rule”, try to make all people taking part in a conversation end up a bit better off than what they were when they started the conversation, and telling people what to do or what not to are going straight against this."

Post-therapy, I'm much better at focusing on changing myself than trying to change others. I'd recommend therapy, but that might be construed as an implicit instruction...

🙌 Twitter Considers Subscription Fee for Tweetdeck, Unique Content — "To explore potential options outside ad sales, a number of Twitter teams are researching subscription offerings, including one using the code name “Rogue One,” according to people familiar with the effort. At least one idea being considered is related to “tipping,” or the ability for users to pay the people they follow for exclusive content, said the people, who asked not to be named because the discussions are internal. Other possible ways to generate recurring revenue include charging for the use of services like Tweetdeck or advanced user features like “undo send” or profile-customization options."

This is fantastic news. It would destroy Twitter as it currently stands, but that's fine as it's much worse than it was a decade ago.

🔒 Do lockdowns work? — "It's absurd thinking, but the sceptics have finally found an argument that cannot be categorically disproved. Lockdowns have a scientific rational: you can't transmit a virus to people you don't meet. Contrary to what Toby says in his article, they also have historic precedents: during the Spanish Flu, cities such as Philadelphia closed shops, churches, schools, bars and restaurants by law (they also made face masks mandatory). And now we have numerous natural experiments from around the world showing that infection rates fall when lockdowns are introduced."

There will always be idiots who try and use their influence and eloquence to ensure they're heard. Thankfully, there are people like this who can dismantle their arguments brick-by-brick.

Quotation-as-title by Jules Renard. Image. by Elena Mozhvilo.

There are many things we despise in order that we may not have to despise ourselves

🇺🇸 Well, that was expected — "I’ve recorded this here since it feels like the chronology of events and the smaller details are already evaporating, and this helps me wrap my head around a tiny fraction of it. If you happen to read this, don’t take this at face value (nor anything else on the web for that matter). Do your own research and correct me if you think any of the timestamps are wrong."

📺 Fox News and the real insurrection — "After Democrats said they planned to impeach Trump again, Fox opinionators echoed the risible Republican talking point that such a move would be provocative; after Twitter banned Trump, they pivoted to bash Big Tech. Yesterday morning, Jeanine Pirro compared Amazon’s decision to boot Parler, an app popular among right-wing extremists, from its web-hosting services to Kristallnacht—the night, in 1938, when Nazis in Germany killed around one hundred Jewish people and arrested tens of thousands more"

₿ Lost Passwords Lock Millionaires Out of Their Bitcoin Fortunes — "Of the existing 18.5 million Bitcoin, around 20 percent — currently worth around $140 billion — appear to be in lost or otherwise stranded wallets, according to the cryptocurrency data firm Chainalysis. Wallet Recovery Services, a business that helps find lost digital keys, said it had gotten 70 requests a day from people who wanted help recovering their riches, three times the number of a month ago."

🕸️ Pirated Academic Database Sci-Hub Is Now on the ‘Uncensorable Web’ — "As evidenced by Sci-Hub’s own problems, the decentralized web is being built out of fears of deplatforming. As the internet’s access points are increasingly centralized in the hands of a few actors, certain applications – most recently, Twitter-alternative Parler – have faced censorship at the hands of web server providers, app stores and DNS certificate authorities."

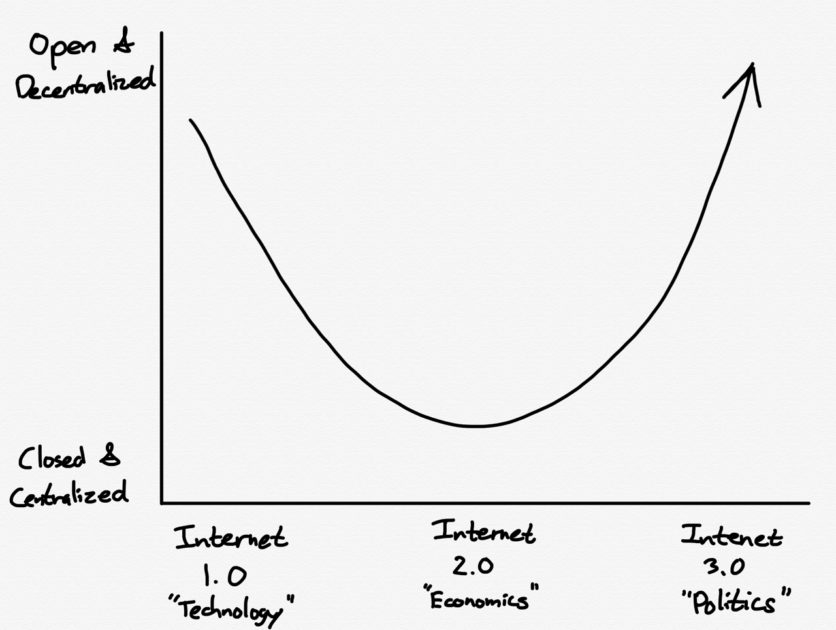

🏛️ Internet 3.0 and the Beginning of (Tech) History — Here technology itself will return to the forefront: if the priority for an increasing number of citizens, companies, and countries is to escape centralization, then the answer will not be competing centralized entities, but rather a return to open protocols. This is the only way to match and perhaps surpass the R&D advantages enjoyed by centralized tech companies; open technologies can be worked on collectively, and forked individually, gaining both the benefits of scale and inevitability of sovereignty and self-determination.

Quotation-as-title by Vauvenargues. Image from bottom-linked post.

Nothing is repeated, and everything is unparalleled

🤔 We need more than deplatforming — "But as reprehensible as the actions of Donald Trump are, the rampant use of the internet to foment violence and hate, and reinforce white supremacy is about more than any one personality. Donald Trump is certainly not the first politician to exploit the architecture of the internet in this way, and he won’t be the last. We need solutions that don’t start after untold damage has been done."

💪 Demands and Responsibilities — "If you demand rights for yourself, you have to demand those same rights for others. You have to take on the responsibility of collective action, and you yourself act in a way that benefits the collective. If you want credit, you have to give credit. If you want community, you have to be communal. If you want to be satiated, you have to allow others to be sated. If you want your vote to be respected, you have to respect the votes of others."

🗯️ Parler Pitched Itself as Twitter Without Rules. Not Anymore, Apple and Google Said. — "Google said in a statement that it had pulled the app because Parler was not enforcing its own moderation policies, despite a recent reminder from Google, and because of continued posts on the app that sought to incite violence."

🙅 Hello! You've Been Referred Here Because You're Wrong About Section 230 Of The Communications Decency Act — "While this may all feel kind of mean, it's not meant to be. Unless you're one of the people who is purposefully saying wrong things about Section 230, like Senator Ted Cruz or Rep. Nancy Pelosi (being wrong about 230 is bipartisan). For them, it's meant to be mean. For you, let's just assume you made an honest mistake -- perhaps because deliberately wrong people like Ted Cruz and Nancy Pelosi steered you wrong. So let's correct that."

🧐 What Wikipedia saw during election week in the U.S., and what we’re doing next — "To help meet this goal, we hope to invest in resources that we can share with international Wikipedia communities that will help mitigate future disinformation risks on the sites. We’re also looking to bring together administrators from different language Wikipedias for a global forum on disinformation. Together, we aim to build more tools to support our volunteer editors, and to combat disinformation."

Quotation-as-title by the Goncourt Brothers. Image from top-linked post.

There are persons who, when they cease to shock us, cease to interest us

It's difficult not to say "I told you so" when things play out exactly as predicted. Four years ago, when Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th President of the USA, many had ominous forebodings.

Donald Trump’s inaugural address was a declaration of war on everything represented by these choreographed civilities. President Trump – it’s time to begin to get used to those jarringly ill-fitting words – did not conjure a deathless phrase for the day. His words will not lodge in the brain in any of the various uplifting ways that the likes of Lincoln, Roosevelt, Kennedy or Reagan once achieved. But the new president’s message could not have been clearer. He came to shatter the veneer of unity and continuity represented by the peaceful handover. And he may have succeeded. In 1933, Roosevelt challenged the world to overcome fear. In 2017, Mr Trump told the world to be very afraid.

The Guardian view on Donald Trump’s inauguration: a declaration of political war (January 2017)

He was all bluster, we were told. That it was rhetoric and would never be followed up with action.

Leaders are judged by their first 100 days in office. Wikipedia has a page outlining what Trump did during his, including things that, looking back from the vantage point of 2021, seem like warning shots: rolling back gun control legislation, stoking fears around voter fraud, cracking down on illegal immigration, freezing federal job hiring (except military), and engaging in tax reform to the benefit of the rich.

As a History teacher, it always struck me as odd that Adolf Hitler, a man born in Austria with brown hair, managed to lead a fascist party that extolled the virtues of being German and having blond hair. These days, I'm equally baffled that some of the richest people in our society — Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees-Mogg — can pass themselves off as 'anti-elite'.

Much of their ability to do so is by creating an alternative reality with the aid of social networks like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. These replace traditional gatekeepers to information with algorithms tweaked for engagement, attention, and profit.

As we know, whipping up hatred and peddling conspiracy theories puts these algorithms into overdrive, and ensure those who agree with the content see what's shared. But this approach also reaches those who don't agree with it, by virtue of people seeking to reject and push back on it. Meanwhile, of course, the platforms rake in $$$ from advertisers.

I get the feeling that there are a great number of people who do not understand the way the world works in 2021. I am probably one of them. In fact, given how much control we've given to algorithms in recent years, perhaps no-one truly understands.

One thing for sure, though, is that banning Donald Trump from Facebook and Instagram indefinitely is too little, too late. These platforms, among with others, downplayed his and other 'alt-right' hate speech for fear of being penalised.

Pandora's Box is open. Those who realise that everything is a construct and theory-laden will control those who don't. The latter will be reduced to merely wandering around an alternative reality, like protesters in Statuary Hall, waiting to be told what to do next.

Quotation-as-title by F.H. Bradley

You can’t tech your way out of problems the tech didn’t create

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), is a US-based non-profit that exists to defend civil liberties in the digital world. They've been around for 30 years, and I support them financially on a monthly basis.

In this article by Corynne McSherry, EFF's Legal Director, she outlines the futility in attempts by 'Big Social' to do content moderation at scale:

[C]ontent moderation is a fundamentally broken system. It is inconsistent and confusing, and as layer upon layer of policy is added to a system that employs both human moderators and automated technologies, it is increasingly error-prone. Even well-meaning efforts to control misinformation inevitably end up silencing a range of dissenting voices and hindering the ability to challenge ingrained systems of oppression.

CORYNNE MCSHERRY, CONTENT MODERATION AND THE U.S. ELECTION: WHAT TO ASK, WHAT TO DEMAND (EFF)

Ultimately, these monolithic social networks have a problem around false positives. It's in their interests to be over-zealous, as they're increasingly under the watchful eye of regulators and governments.

We have been watching closely as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, while disclaiming any interest in being “the arbiters of truth,” have all adjusted their policies over the past several months to try arbitrate lies—or at least flag them. And we’re worried, especially when we look abroad. Already this year, an attempt by Facebook to counter election misinformation targeting Tunisia, Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, and seven other African countries resulted in the accidental removal of accounts belonging to dozens of Tunisian journalists and activists, some of whom had used the platform during the country’s 2011 revolution. While some of those users’ accounts were restored, others—mostly belonging to artists—were not.

Corynne McSherry, Content Moderation and the U.S. Election: What to Ask, What to Demand (EFF)

McSherry's analysis is spot-on: it's the algorithms that are a problem here. Social networks employ these algorithms because of their size and structure, and because of the cost of human-based content moderation. After all, these are companies with shareholders.

Algorithms used by Facebook’s Newsfeed or Twitter’s timeline make decisions about which news items, ads, and user-generated content to promote and which to hide. That kind of curation can play an amplifying role for some types of incendiary content, despite the efforts of platforms like Facebook to tweak their algorithms to “disincentivize” or “downrank” it. Features designed to help people find content they’ll like can too easily funnel them into a rabbit hole of disinformation.

CORYNNE MCSHERRY, CONTENT MODERATION AND THE U.S. ELECTION: WHAT TO ASK, WHAT TO DEMAND (EFF)

She includes useful questions for social networks to answer about content moderation:

But, ultimately...

You can’t tech your way out of problems the tech didn’t create. And even where content moderation has a role to play, history tells us to be wary. Content moderation at scale is impossible to do perfectly, and nearly impossible to do well, even under the most transparent, sensible, and fair conditions

CORYNNE MCSHERRY, CONTENT MODERATION AND THE U.S. ELECTION: WHAT TO ASK, WHAT TO DEMAND (EFF)

I'm so pleased that I don't use Facebook products, and that I only use Twitter these days as a place to publish links to my writing.

Instead, I'm much happier on the Fediverse, a place where if you don't like the content moderation approach of the instance you're on, you can take your digital knapsack and decide to call another place home. You can find me here (for now!).

When people are free to do as they please, they usually imitate each other

🙆 How I talk to the victims of conspiracy theories

🔒 The Github youtube-dl Takedown Isn't Just a Problem of American Law

🖥️ The Raspberry Pi 400 - Teardown and Review

🐧 As a former social media analyst, I'm quitting Twitter

Quotation-as-title by Eric Hoffer. Image from top-linked post.

Collaboration is our default operating system

One of the reasons I'm not active on Twitter any more is the endless, pointless arguments between progressives and traditionalists, between those on the left of politics and those on the right, and between those who think that watching reality TV is an acceptable thing to spend your life doing, and those who don't.

Interestingly a new report which draws on data from 10,000 people, focus groups, and academic interviews suggests that half of the controversy on Twitter is generated by a small proportion of users:

[The report] states that 12% of voters accounted for 50% of all social-media and Twitter users – and are six times as active on social media as are other sections of the population. The two “tribes” most oriented towards politics, labelled “progressive activists” and “backbone Conservatives”, were least likely to agree with the need for compromise. However, two-thirds of respondents who identify with either the centre, centre-left or centre-right strongly prefer compromise over conflict, by a margin of three to one.

Michael Savage, ‘Culture wars’ are fought by tiny minority – UK study (The Observer)

Interestingly, the report also shows difference between the US and UK, but also to attitudes before and after the pandemic started:

The research also suggested that the Covid-19 crisis had prompted an outburst of social solidarity. In February, 70% of voters agreed that “it’s everyone for themselves”, with 30% agreeing that “we look after each other”. By September, the proportion who opted for “we look after each other” had increased to 54%.

More than half (57%) reported an increased awareness of the living conditions of others, 77% feel that the pandemic has reminded us of our common humanity, and 62% feel they have the ability to change things around them – an increase of 15 points since February.

MICHAEL SAVAGE, ‘CULTURE WARS’ ARE FOUGHT BY TINY MINORITY – UK STUDY (THE OBSERVER)

As I keep on saying, those who believe in unfettered capitalism have to perpetuate a false narrative of competition in all things to justify their position. We have more things in common than differences, and I truly believe the collaboration is our default operating system.

Saturday sailings

I deactivated my Twitter account this week. I've done that before, but this time I'm honestly not sure if I'll reactivate it.

Given that I get a fair few links through Twitter, I wonder if the kind of things I share in these weekly link roundups will change? We shall see, I guess. You can connect with me via the Fediverse: https://mastodon.social/@dajbelshaw

33 Myths of the System

Drawing on the entire history of radical thought, while seeking to plumb their common depths, 33 Myths of the System, presents a synthesis of independent criticism, a straightforward exposure of the justifications of the world-system, along with a new way to perceive and understand the unhappy supermind that directs, penetrates and even lives our lives.

Darren Allen

While I didn't agree with absolutely everything in this free e-book, it's fair to say it blew my mind. Highly recommended, especially for thoughtful people. One of the best things I've read in the last decade in terms of getting me to question... everything.

A catastrophe at Twitter

In any case, Twitter’s response to the incident offered further cause for distress. The company’s initial tweet on the subject said almost nothing, and two hours later it had followed only to say what many users were forced to discover for themselves: that Twitter had disabled the ability of many verified users to tweet or reset their passwords while it worked to resolve the hack’s underlying cause.

The near-silencing of politicians, celebrities, and the national press corps led to much merriment on the service — see this, along with Those good tweets below, for some fun — but the move had other, darker implications. Twitter is, for better and worse, one of the world’s most important communications systems, and among its users are accounts linked to emergency medical services. The National Weather Service in Lincoln, IL, for example, had just tweeted a tornado warning before suddenly going dark. To the extent that anyone was relying on that account for further information about those tornadoes, they were out of luck.

Casey Newton (The INterface)

I didn't actually deactivate my Twitter account because of the hack — that was actually more to do with the book mentioned above — but as a verified user, this certainly reinforced my decision. Just a reminder that at least one person with nuclear codes uses Twitter as their primary means of communication.

This is Fine: Optimism & Emergency in the P2P Network

Centralised platforms crave data collection and thirst for trust from the communities they seek to exploit. These platforms sell bloated, overpowered hardware that cannot be repaired, vulnerable to drops in consumer spending or spasms in the supply chain. They anxiously eye legislation to compel encryption backdoors, which will further weaken the trust they need so badly. They wobble beneath network disruptions (such as the worldwide slowdowns in March under COVID-19 load surges) that incapacitate cloud-dependent devices. They sleep with one eye open in countries where authoritarian governments compel them or their employees to operate as an informal arm of enforcement. These current trajectories point to the accelerating erosion of centralised platform power.

Cade Diehm (The New Design Congress)

This is an incredible article that's very well presented. I keep talking about the importance of decentralisation, and this article backs that up — but also explains how and why decentralised social networks need to do better.

Our remote work future is going to suck

While the upsides to remote work are true, for many people remote work is a poison pill — one where you are given “control” in the name of productivity in exchange for some pretty nasty long-term effects.

In reality, remote work makes you vulnerable to outsourcing, reduces your job to a metric, creates frustrating change-averse bureaucracies, and stifles your career growth. The lack of scrutiny our remote future faces is going to result in frustrated workers and ineffective companies.

Sean Blanda

I'm a proponent of remote work, but I was nodding along to many of the points made in this post. Context is everything, and there's something to be said about being able to go home to escape work.

CO2 emissions on the web

Your content site probably doesn’t need JavaScript. You probably don’t need a CSS framework. You probably don’t need a custom font. Use responsive images. Extend your HTTP cache lifetimes. Use a static site generator or wp2static.com instead of dynamically generating each page on the fly, despite never changing. Consider ditching that third-party analytics service that you never look at anyway, especially if they also happen to sell ads. Run your website through websitecarbon.com. Choose a green web host.

Danny van Kooten

This week I changed the theme over at my personal blog to one that is much lighter. When I shared what I'd done on Mastodon, someone commented that they didn't think it would make that much difference. This post was written by someone who popped up to rebut what they said.

Ask a Sane Person: Jia Tolentino on Practicing the Discipline of Hope

INTERVIEW: What has this pandemic confirmed or reinforced about your view of society?

TOLENTINO: That capitalist individualism has turned into a death cult; that the internet is a weak substitute for physical presence; that this country criminally undervalues its most important people and its most important forms of labor; that we’re incentivized through online mechanisms to value the representation of something (like justice) over the thing itself; that most of us hold more unknown potential, more negative capability, than we’re accustomed to accessing; that the material conditions of life in America are constructed and maintained by those best set up to exploit them; and that the way we live is not inevitable at all.

Christopher Bollen

I have to confess to not knowing who Jia Tolentino was before stumbling across this via the Hurry Slowly newsletter (although I must have read her writing before). This is a fantastic interview, which you should read in its entirety.

Header image by Fab Lentz

The shoe that fits one person pinches another; there is no recipe for living that suits all cases

Twitter, the Fediverse, and MoodleNet

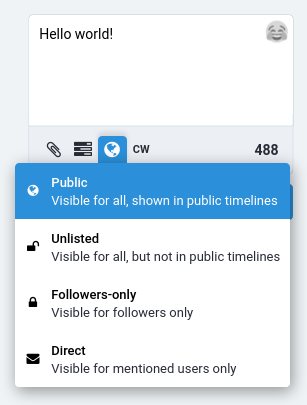

In a recent blog post, Twitter made a big deal of the fact that they are testing new conversation settings.

While some people don't necessarily think this is a good idea, I think it's a step forward. In fact, I've actually already tried out this functionality... on the Fediverse.

The Fediverse (a portmanteau of "federation" and "universe") is the ensemble of federated (i.e. interconnected) servers that are used for web publishing (i.e. social networking, microblogging, blogging, or websites) and file hosting, but which, while independently hosted, can intercommunicate with each other.

Wikipedia

That's a mouthful. Let's get to the details of that in a moment and deal with a concrete example instead. Here is a screenshot showing what Twitter has learned from Mastodon (and other federated social networks) in terms of how to make conversations better.

The Fediverse feels like a very different place to Twitter. There's a reason why you will find the marginalised, the oppressed, and very niche interests here: it's a safe space. And, despite macho right-leaning posturing, we all need spaces online where we can be ourselves.

Of course 'federation' and 'decentralisation' aren't words that most of us tend to use on a day-to-day basis. So it's important to define terms here so you can see the inherent difference between using something like Twitter and something like Mastodon.

Note: I can pretty much guarantee by 2030 you'll be using a federated social network of some description. After all, in 2007 people told me Twitter would never catch on, yet a few years later pretty much everyone was using it.)

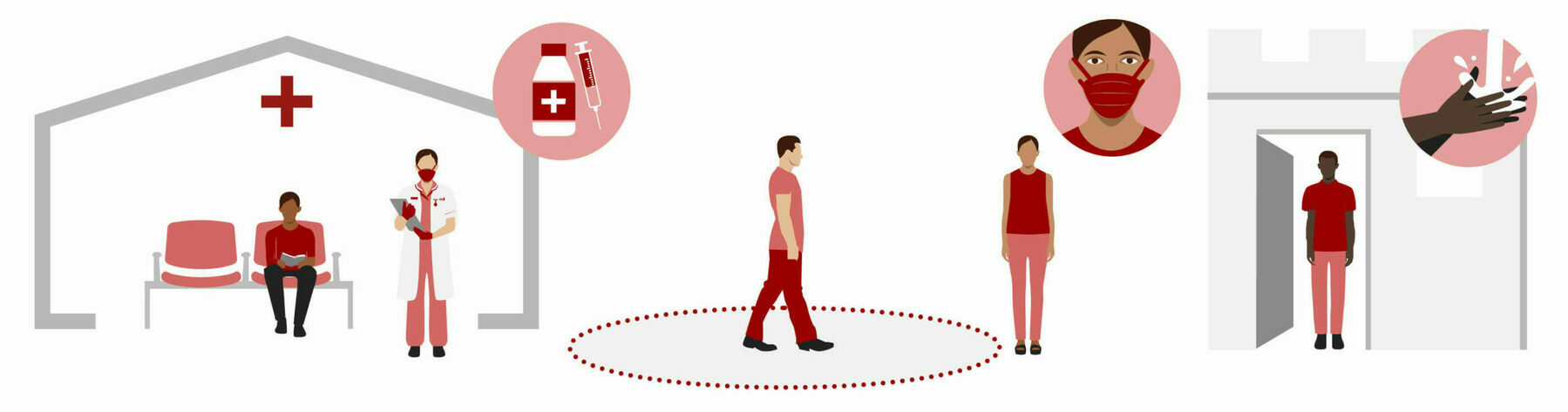

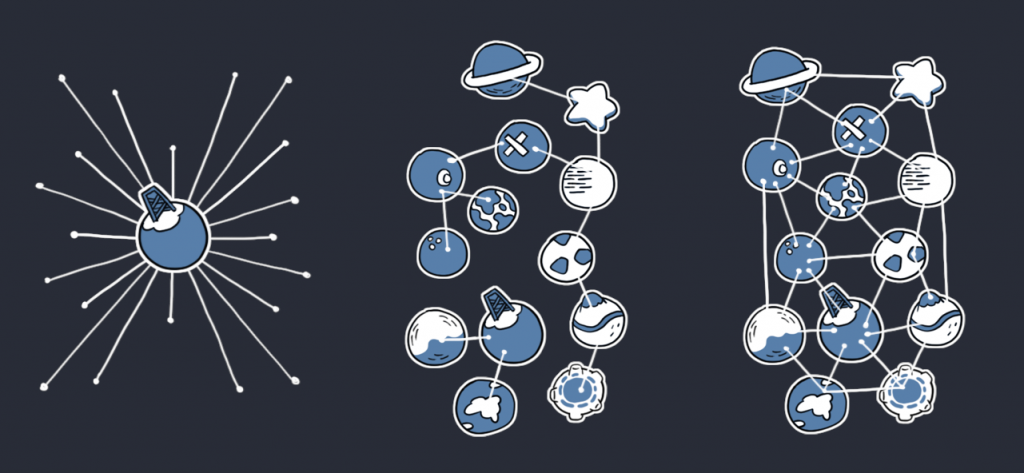

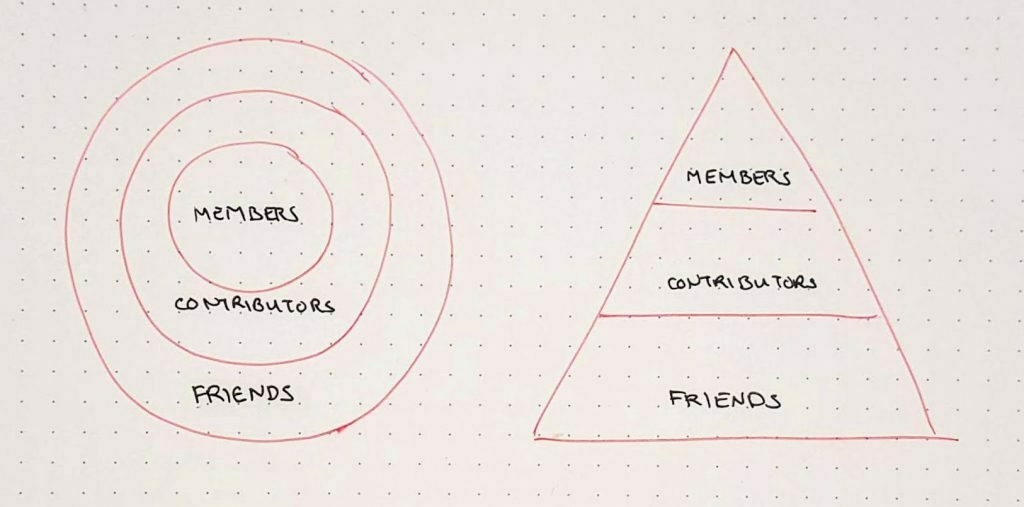

Check out the diagram above. On the left, is the representation of a centralised platform. An example of that would be Facebook. You're either on Facebook, or you're not on Facebook. I don't use any of Facebook's products out of a concern for privacy, civil liberties, and the threat they pose to democracy. As a result, my ethical stance means that anything posted to Facebook, Instagram, or WhatsApp is inaccessible to me.It's either have an account on their servers, or you don't.

On the right of the diagram, you can the representation of a distributed social network. Here, every server has a copy of what is on every other server. This is how bittorrent works, and is great for resilience and ensuring things are fault-tolerant. There are a couple of examples of social networks that use this approach (e.g. Scuttlebutt), but they're primarily used for situations where users have intermittent internet access.

Then, in the middle is a federated social network. This is what I'm focusing on in this article. It's kind of how email works; you can email anyone else in the world no matter which email platform they use. GMail users email Outlook users email Fastmail users. Only the data you send and receive with the person you are communicating with resides on each email server; you don't have a copy of everyone in the whole network's email!

So, just as with email, federated social networks have an underlying protocol to ensure that messages from one platform can be understood, displayed, and replied to by another. Those making the platform, of course, have to bake that functionality in; Facebook, Twitter, and the like choose not to do so.

What does this mean in practice? Well, let's take three examples. The first is around 10 years ago when I decided to delete my Facebook account. That means I haven't had an account there, or been able to access any non-public information on that social network for a decade.

On the other hand, about five years ago, I ditched GMail for Protonmail because I wanted to improve the privacy and security of my personal email account. Leaving GMail didn't mean giving up having an email account.

Likewise, a couple of years ago, I decided to leave my Mastodon-powered social.coop account as I was getting some hassle. Instead of quitting the social network, as I would have had to do if this had happened on Facebook, I could quickly and easily move my account to mastodon.social. All of my settings were imported, including all of the people I was following!

An aside about moderation. What Twitter is doing with its new functionality is giving its users tools to do some of their own moderation. Other than that, the only moderation possible within the Twitter network is to 'report' tweets for spam or abuse. Moderators, acting on a network-wide scale then need to figure out whether the tweet contravened their guidelines. Having reported tweets before, this can take days and is often not resolved to anyone's satisfaction.

Contrast that with the Fediverse, where people join instances depending on a range of factors including their geographic location, languages spoken, political and religious beliefs, tolerance for profanity, and so on. Fediverse users are accessing the wider network through a server that is moderated by people they trust. If they stop trusting those moderators they can move their account elsewhere, or even host their own server.

This leads to much faster, more local, and more effective moderation. Instance-level blocking is common, as it should be. After all, you have the right to discuss with other people things I find hateful, but it doesn't mean I have to see them on my timeline.

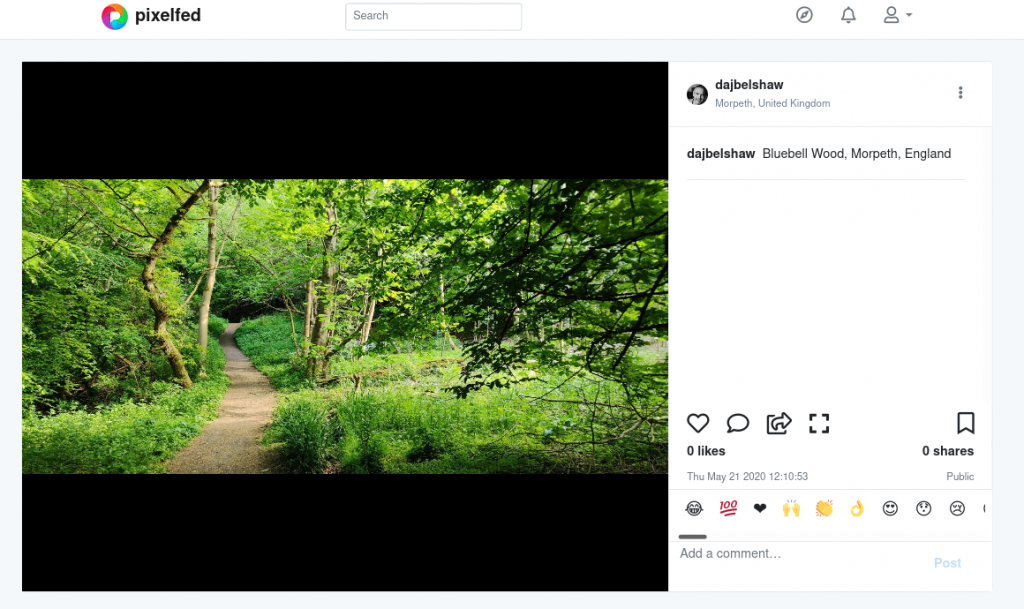

You may be wondering about what how this looks and feels in practice. The above screenshot is from PixelFed, a federated social network that is a bit like Instagram. The difference, as I'm sure you've already guessed, is that it's federated!

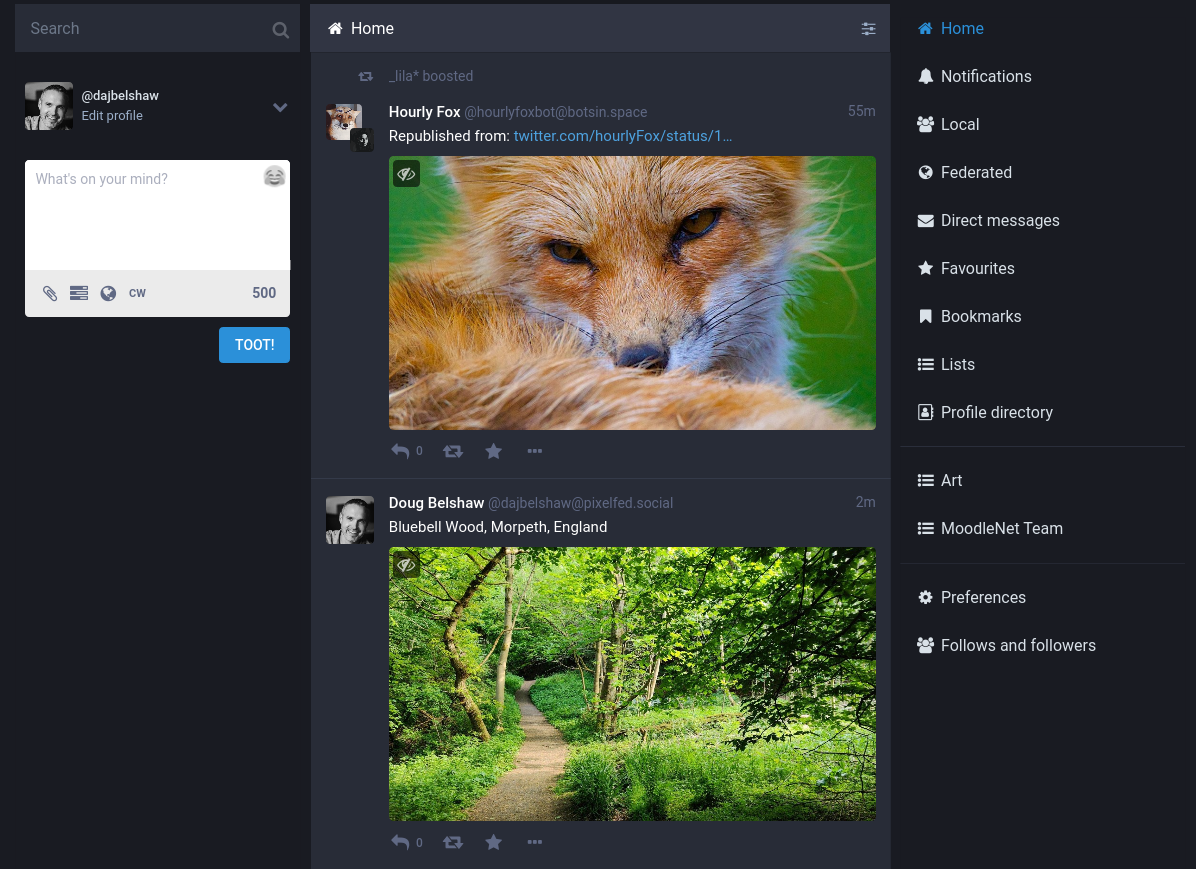

Check out the two posts on my Mastodon timeline above.

The top post is an example of someone on Mastodon 'republishing' the same thing they've posted on Twitter. They've literally had to do the manual work of separately uploading the image and entering the text on each social network, and have to maintain two separate accounts.

The bottom post, on the other hand, is my PixelFed post showing up in my Mastodon feed. No extra work was involved here: anyone's Mastodon account can follow anyone's PixelFed account, and it's all down to the magic of open, federated protocols. In this case, ActivityPub.

There are many federated social networks — many more, in fact, than are listed on the Wikipedia page for Fediverse. One of my favourites is Misskey just because it's so... Japanese. You can choose whatever suits you, and everything works together.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation said back in 2011 when writing about federated social networks:

The best way for online social networking to become safer, more flexible, and more innovative is to distribute the ability and authority to the world's users and developers, whose various needs and imaginations can do far more than what any single company could achieve.

Richard Esguerra (EFF)

As many people reading this will be aware, I have skin in this game, a dog in this fight, a horse in this race because of MoodleNet. The difference is that MoodleNet is not only a federated social network, but a decentralised digital commons. Educators join communities to curate collections of openly-licensed resources.

This poses additional design challenges to those faced by existing federated social networks. We're pretty close now to v1.0 beta and have built upon the fantastic thinking and approaches of other federated social networks. In addition, we've added functionality that is specific (at the moment, at least) to MoodleNet, and suits our target audience.

No video above? Try this!

So not so much as a 'conclusion' to this particular piece of writing as a screencast video to show you what I mean with MoodleNet, as well as the judicious use of this emoji: 🤔

Quotation-as-title from Carl Jung. Header image by Md. Zahid Hasan Joy

Saturday seductions

Having a Bank Holiday in the UK on a Friday has really thrown me this week. So apologies for this link roundup being a bit later than usual...

I do try to inject a little bit of positivity into these links every week, but the past few days have made me a little concerned about our post-pandemic future. Anyway, here goes...

Radio Garden

This popped up in my Twitter feed this week and brought joy to my life. So simple but so effective: either randomly go to, or browse radio stations around the world. The one featured in the screenshot above is one close to me I forgot existed!

COVID and forced experiments

Every time we get a new kind of tool, we start by making the new thing fit the existing ways that we work, but then, over time, we change the work to fit the new tool. You’re used to making your metrics dashboard in PowerPoint, and then the cloud comes along and you can make it in Google Docs and everyone always has the latest version. But one day, you realise that the dashboard could be generated automatically and be a live webpage, and no-one needs to make those slides at all. Today, sometimes doing the meeting as a video call is a poor substitute for human interaction, but sometimes it’s like putting the slides in the cloud.

I don’t think we can know which is which right now, but we’re going through a vast, forced public experiment to find out which bits of human psychology will align with which kinds of tool, just as we did with SMS, email or indeed phone calls in previous generations.

Benedict Evans

An interesting post that both invokes 'green eggs and ham' as a metaphor, and includes an anecdote from an Ofcom report towards the end about a woman named Polly that no-one who does training or usability testing should ever forget.

Education is over…

What future learning environments need is not more mechanization, but more humanization; not more data, but more wisdom; not more

William Rankin (regenerative.global)

objectification, but more subjectification; not more Plato, but more Aristotle.

I agree, although 'subjectification' is a really awkward word that suggests school subjects, which isn't the author's point. After all of this, I can't see parents, in particular, accepting going back to how school has been. At least, I hope not.

What Happens Next?

This guide... is meant to give you hope and fear. To beat COVID-19 in a way that also protects our mental & financial health, we need optimism to create plans, and pessimism to create backup plans. As Gladys Bronwyn Stern once said, “The optimist invents the airplane and the pessimist the parachute.”

Marcel Salathé & Nicky Case

Modelling what happens next in terms of lockdowns, etc. is not an easy think to understand, and there are many competing opinions. This guide, with 'playable simulations' is the best thing I've seen so far, and I feel I'm much better prepared for the next decade (yes, you read that correctly).

Sheltering in Place with Montaigne

By the time Michel de Montaigne wrote “Of Experience,” the last entry in his third and final book of essays, the French statesman and author had weathered numerous outbreaks of plague (in 1585, while he was mayor of Bordeaux, a third of the population perished), political uprisings, the death of five daughters, and an onslaught of physical ailments, from rotting teeth to debilitating kidney stones.

[...]

The ubiquity of suffering heightened Montaigne’s attentiveness to the complexity of human experience. Pleasure, he contends, flows not from free rein but structure. The brevity of existence, he goes on, gives it a certain heft. Exertion, truth be told, is the best form of compensation. Time is slippery, the more reason to grab hold.

Drew Bratcher (The Paris Review)

Montaigne is one of my favourite authors, and having recently read Stefan Zweig's bioraphy of him, he feels even more relevant to our times.

Clarity for Teachers: Day 42

There’s a children’s book that I love, The Greentail Mouse by Leo Lionni. It plays on the old theme of the town mouse and the country mouse. In this telling, the town mouse comes to visit his cousins in their rural idyll, and they ask him about life in the town. It’s horrible, he says, noisy and dangerous, but there is one day a year when it’s amazing, and that’s when carnival comes around. So the country mice decide to hold a carnival of their own: they make costumes and masks, they grunt and shriek and howl and jump around like wild things. But then, at some point, they forget that they are wearing masks; they end up believing that they are the fierce creatures they have been playing at being, and their formerly peaceful community becomes filled with fear, hatred and suspicion.

Dougald Hine

Dougald Hine is taking Charlie Davies' course Clarity for Teachers and is blogging each day about it. This is from the last post in the series. I'm including it partly to point towards Homeward Bound, which I've just signed up for, and which starts next Thursday.

BBC Archive: Empty sets

Give your video calls a makeover, with this selection of over 100 empty sets from the BBC Archive.

Who hasn't wanted to host a pub quiz from the Queen Vic, conduct a job interview from the confines of Fletch's cell, or catch up with friends and family from the bridge of the Liberator in Blake's 7?

I love this idea, to spice up Zoom calls, etc.

People you follow

First I search for my new item of interest, then I filter the results by “People I Follow.” (You can try it out with some of my recent searches: “Roger Angell,” “Captain Beefheart,” and “Rockford Files.”) Depending on the subject, I might have pages and pages of links, all handily selected for me by people I find interesting.

Austin Kleon

In his most recent newsletter, Austin Kleon referenced this post of his from five years ago. I think the idea is a great one and I'll definitely be doing this in future! Twitter move settings around occasionally, but it's still there under 'search filters'.

68 Bits of Unsolicited Advice

Perhaps the most counter-intuitive truth of the universe is that the more you give to others, the more you’ll get. Understanding this is the beginning of wisdom.

Before you are old, attend as many funerals as you can bear, and listen. Nobody talks about the departed’s achievements. The only thing people will remember is what kind of person you were while you were achieving.

Over the long term, the future is decided by optimists. To be an optimist you don’t have to ignore all the many problems we create; you just have to imagine improving our capacity to solve problems.

Kevin Kelly (The Technium)

The venerable KK is now 68 years of age and so has dispensed some wisdom. It's a mixed bag, but I particularly liked these the three bits of advice I've quoted above.

Header image by Ben Jennings.

People seem not to see that their opinion of the world is also a confession of character

Actions, reactions, and what comes next

We are, I would suggest, in a period of collective shock due to the pandemic. Of course, some people are better at dealing with these kinds of things than others. I'm not medically trained, but I'm pretty sure some of this comes down to genetics; it's probably something to do with the production of cortisol.

It might a little simplistic to separate people into those who are good in a crisis and those who aren't. It's got to be more complex than that. What if some people, despite their genetic predisposition, have performed some deliberate practice in terms of how they react to events and other things around them?

I often say to my kids that it's not your actions that mark you out as a person, but your reactions. After all, anyone can put on a 'mask' and affect an air of nonchalance and sophistication. But that mask can slip in a crisis. To mix metaphors, people lose control when they reach the end of their tether, and are at their most emotionally vulnerable and unguarded when things go wrong. This is when we see their true colours.

A few years ago, when I joined Moodle, I flew to Australia and we did some management bonding stuff and exercises. One of them was about the way that you operate in normal circumstances, and the way that you operate under pressure. Like most people, I tended to get more authoritarian in a crisis.

What we're seeing in this crisis, I think, are people's true colours. The things they're talking about the most and wanting to protect are the equivalent of them item they'd pull from a burning building. What do they want to protect from the coronavirus? Is it the economy? Is it their family? Is it freedom of speech?

Last week, I asked Thought Shrapnel supporters what I should write about. It was suggested that I focus on something beyond the "reaction and hyperaction" that's going on, and engage in "a little futurism and hope". Now that it's no longer easier to imagine the end of the world as the end of capitalism, how do we prepare for what comes next?

It's an interesting suggestion for a thought experiment. Before we go any further, though, I want to preface this by saying these are the ramblings of an incoherent fool. Don't make any investment decisions, buy any new clothes, or sever any relationships based on what I've got to say. After all, at this point, I'm mostly for rhetorical effect.

The first and obvious thing that I think will happen as a result of the pandemic is that people will get sick and some will die. Pretty much everyone on earth will either lose someone close to them or know someone who has. Death, as it has done for much of human history, will stalk us, and be something we are forced to both confront and talk about.

This may not seem like a very cheerful and hopeful place to start, but, actually, not being afraid to die seems to be the first step in living a fulfilling life. As I've said before, quoting it is the child within us that trembles before death. Coming to terms with that fact that you and the people you love are going to die at some point is just accepting the obvious.

If we don't act like we're going to live forever, if we confront our mortal condition, then it forces us to make some choices, both individually and as a society. How do we care for people who are sick and dying? How should we support those who are out of work? What kind of education do we want for our kids?

I forsee a lot of basic questions being re-asked and many assumptions re-evaluated in the light of the pandemic. Individually, in communities, and as societies, we'll look back and wonder why it was that companies making billions of dollars when everything was fine were all of a sudden unable to meet their financial obligations when things weren't going so well. We'll realise that, at root, the neoliberalist form of capitalism we've been drinking like kool-aid actually takes from the many and gives to the few.

Before the pandemic, we had dead metaphors for both socialism and "pulling together in times of adversity". Socialism has been unfairly caricatured as, and equated with, the totalitarian communist experiment in Russia. Meanwhile, neoliberals have done a great job at equating adversity with austerity, invoking memories of life during WWII. Keep Calm and Carry On.

This is why, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, despite the giant strides and inroads into our collective consciousness, made by the Occupy movement, it ultimately failed. When it came down to brass tacks, we were frightened that destroying our current version of capitalism would mean we'd be left with totalitarian communism: queuing for food, spying on your neighbours, and suchlike.

So instead we invoked the only "pulling together in times of adversity" meme we knew: austerity. Unfortunately, that played straight into the hands of those who were happy to hollow out civic society for financial gain.

Post-pandemic, as we're rebuilding society, I think that not only will there be fewer old people (grim, but true) but the overall shock will move the Overton Window further to left than it has been previously. Those who remain are likely to be much more receptive to the kind of socialism that would make things like Universal Basic Income and radically decarbonising the planet into a reality.

Making predictions about politics is a lot easier than making predictions about technology. That's for a number of reasons, including how quickly the latter moves compared to the former, and also because of the compound effect that different technologies can have on society.

For example, look at the huge changes in the last decade around smartphones now being something that people spend several hours using each day. A decade ago we were concerned about people's access to any form of internet-enabled device. Now, we just assume that everyone's gone one which they can use to connect during the pandemic.

What concerns me is that the past decade has seen not only the hollowing-out of civic society in western democracies, but also our capitulation to venture capital-backed apps that make our lives easier. The reason? They're all centralised.

I'm certainly not denying that some of this is going to make our life much easier short-term. Being on lockdown and still being able to have Amazon deliver almost anything to me is incredible. As is streaming all of the things via Netflix, etc. But, ultimately, caring doesn't scale, and scaling doesn't care.

Right now, we relying on centralised technologies. Everywhere I look, people are using a apps, tools, and platforms that could go down at any time. Remember the Twitter fail whale?

What happens when that scenario happens with Zoom? Or Microsoft Teams? Or Slack, or any kind of service that relies on the one organisation having their shit together for an extended period of time during a pandemic?

I think we're going to see outages or other degradations in service. I'm hoping that this will encourage people to experiment with other, decentralised platforms, rather than leap from the frying pan of one failed centralised service into the fire another.

In terms of education, I don't think it's that difficult to predict what comes next. While I could be spectacularly wrong, the longer kids are kept at home and away from school, the more online teaching and learning has to become something mainstream.

Then, when it's time to go back to school, some kids won't. They and their parents will realise that they don't need to, or that they are happier, or have learned more staying at home. Not all, by any means, but a significant majority. And because everyone has been in the same boat, parents will have peer support in doing so.

The longer the pandemic lockdown goes on, the more educational institutions will have to think about the logistics and feasibility of online testing. I'd like to think that competency-based learning and stackable digital credentials like Open Badges will become the norm.

Further out, as young people affected by the pandemic lockdown enter the job market, I'd hope that they would reject the traditional CV or resume as something that represents their experiences. Instead, although it's more time-consuming to look at, I'd hope for portfolio-based approaches (with verified digital credentials) to become standard.

Education isn't just about, or even mainly about, getting a job. So what about the impact of the pandemic on learners? On teachers? Well, if I'm being optimistic and hopeful, I'd say that it shows that things can be done differently at scale.

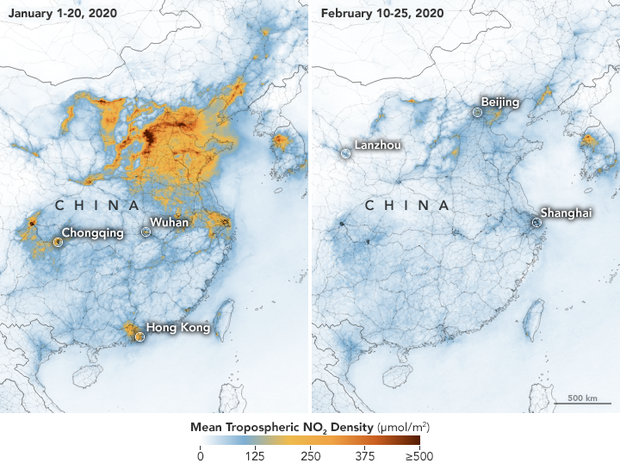

In the same way that climate change-causing emissions dropped dramatically in China and other countries during the enforced coronavirus lockdown, so we can get rid of the things we know are harmful in education.

High-stakes testing? We don't need it. Kids being taught in classes of 30+ by a low-paid teacher? Get over it. Segregation between rich and poor through private education? Reject it.

All of this depends on how we respond to the 'shock and awe' of both the pandemic and its response. We're living during a crisis when it's almost certainly necessary to bring in the kind of authoritarian measures we'd reject at any other time. While we need to move quickly, we still need to subject legislation and new social norms to some kind of scrutiny.

This period in history provides us with a huge opportunity. When I was a History teacher, one of my favourite things to teach kids was about revolutions; about times when people took things into their own hands. There's the obvious examples, for sure, like 1789 and the French Revolution.

But perhaps my absolute favourite was for them to discover what happened after the Black Death ravaged Europe in particular in the 14th century. Unable to find enough workers to work their land, lords had to pay peasants several times what they could have previously expected. In fact, it led to the end of the entire feudal system.

We have the power to achieve something similar here. Except instead of serfdom, the thing we can escape from his neoliberal capitalism, the idea that the poor should suffer for the enrichment of the elite. We can and should structure our society so that never happens again.

In other words, never waste a crisis. What are you doing to help the revolution? Remember, when it comes down to it, power is always taken, never freely given.

BONUS: after writing this, I listened to a recent a16z podcast on Remote Work and Our New Reality. Worth a listen!

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup, become a supporter, or download Thought Shrapnel Vol.1: Personal Productivity!

Quotation-as-title by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Header image by Ana Flávia.

Given things as they are, how shall one individual live?

...asked Annie Dillard. It's a good question.

Richard D. Bartlett, who I support via Patreon and who is better known as richdecibels, has started a newsletter. The process of signing up for it reminded me of a post he wrote last year entitled Hierarchy Is Not The Problem...

Ten years ago, in my first foray into senior management, I was told by a consultant to the newly-installed Principal that "he's very hierarchical". She meant it in a good way, but I almost quit on the spot. To me, that's shorthand for a very dictatorial style of management.

So Bartlett's post, which I think I've mentioned before, is one I keep coming back to. He says that:

I don’t care about hierarchy. It’s just a shape. I care about power dynamics.

[...]

These days I have mostly removed “non-hierarchical” from my vocabulary. I still haven’t found a great replacement, but for now I say “decentralised”. But again, it’s not the shape that’s interesting, it’s the power dynamics.

Richard D. Bartlett

That's quite a challenging notion for me, having been in situations within very hierarchical organisations where people try and put me in a box, tie me to a particular role, or otherwise indicate I should stick to my own lane.

It's something I'm continue to process. I'm not sure whether Bartlett's correct. It's a great argument, and I've certainly seen some great organisations structured by way of what I'd call the "default operating system" of hierarchy.

Perhaps the thing is that it's easy to show the difference between the way an organisation is structured (its nodes) as opposed to the the difference between the way those nodes connect with one another. Interactions between other human beings are complicated, and difficult to put in a neat diagram.

Recently, Sam Altman, President of the famed startup accelerator Y Combinator, wrote a Twitter thread which he entitled How To Be Successful At Your Career. It's what people do instead of blogging these days, it would appear.

One tweet in the thread really stuck out to me, especially in this context of hierarchy and coercive power relationships:

The most successful people (judged by history, not money) continually look for the most important thing they are able to work on, and that’s what they do. They do not get trapped in local maxima, and they do not deceive themselves if they find something more important.

Sam Altman

In other words, what you're attempting to do should transcend the organisation you currently work for and the people with whom you currently work. I believe Steve Jobs called this "making a dent in the universe". It's unlikely to happen if you're playing politics within your organisation, if you're abusing a position of power, or you're spending all day in meetings.

Fred Wilson, a VC, says he often gets asked what to work on. This is understandable, given it's his job to keep his finger on the pulse of companies in which he can invest. Wilson sums up by saying:

You must work on something that inspires you and others, you must work on something with a significant impact, and you must do it in a way that makes getting where you want to go as easy as possible and keeps you there as long as possible.

Fred Wilson

I think this is a good mantra, and I appreciate that he doesn't just consider 'impact' to be 'financial impact', but also "how it changes the way people think and how they react to your product or service or innovation".

Context is really important. It's the reason why there is no one-size-fits-all approach to organisational structures, and why, unless you're the founder of the organisation, you will never be 100% aligned with everything it does. And even then, if your organisation grows to make an impact, there will be a difference between you and the organisation you helped to gestate.

All we can do, at any given point, is to weigh up where we are, using principles such as Fred Wilson's:

As Altman writes, that's likely to be in a place that doesn't play politics and, to Bartlett's point, it's important to pay very close attention to power dynamics. In short, it's important to ask ourselves regularly, "Am I best positioned to make the particular dent I've decided to make in the universe?"

Friday fawnings

On this week's rollercoaster journey, I came across these nuggets:

Image via xkcd

People will come to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think

So said Neil Postman (via Jay Springett). Jay is one of a small number of people who's work I find particularly thoughtful and challenging.

Another is Venkatesh Rao, who last week referenced a Twitter thread he posted earlier this year. It's awkward to and quote the pertinent parts of such things, but I'll give it a try:

Megatrend conclusion: if you do not build a second brain or go offline, you will BECOME the second brain.

[...]

Basically, there's no way to actually handle the volume of information and news that all of us appear to be handling right now. Which means we are getting augmented cognition resources from somewhere. The default place is "social" media.

[...]

What those of us who are here are doing is making a deal with the devil (or an angel): in return for being 1-2 years ahead of curve, we play 2nd brain to a shared first brain. We've ceded control of executive attention not to evil companies, but… an emergent oracular brain.

[...]

I called it playing your part in the Global Social Computer in the Cloud (GSCITC).

[...]

Central trade-off in managing your participation in GSCITC is: The more you attempt to consciously curate your participation rather than letting it set your priorities, the less oracular power you get in return.

Venkatesh Rao

He reckons that being fully immersed in the firehose of social media is somewhat like reading the tea leaves or understanding the runes. You have to 'go with the flow'.

Rao uses the example of the very Twitter thread he's making. Constructing it that way versus, for example, writing a blog post or newsletter means he is in full-on 'gonzo mode' versus what he calls (after Henry David Thoreau) 'Waldenponding'.

I have been generally very unimpressed with the work people seem to generate when they go waldenponding to work on supposedly important things. The comparable people who stay more plugged in seem to produce better work.

My kindest reading of people who retreat so far it actually compromises their work is that it is a mental health preservation move because they can't handle the optimum GSCITC immersion for their project. Their work could be improved if they had the stomach for more gonzo-nausea.

My harshest reading is that they're narcissistic snowflakes who overvalue their work simply because they did it.

Venkatesh Rao

Well, perhaps. But as someone who has attempted to drink from that firehouse for over a decade, I think the time comes when you realise something else. Who's setting the agenda here? It's not 'no-one', but neither is it any one person in particular. Rather the whole structure of what can happen within such a network depends on decisions made other than you.

For example, Dan Hon, pointed (in a supporter-only newsletter) to an article by Louise Matsakis in WIRED that explains that the social network TikTok not only doesn't add timestamps to user-generated content, but actively blocks the clock on your smartphone. These design decisions affect what can and can't happen, and also the kinds of things that do end up happening.

Writing in The Guardian, Leah McLaren writes about being part of the last generation to really remember life before the internet.

In this age of uncertainty, predictions have lost value, but here’s an irrefutable one: quite soon, no person on earth will remember what the world was like before the internet. There will be records, of course (stored in the intangibly limitless archive of the cloud), but the actual lived experience of what it was like to think and feel and be human before the emergence of big data will be gone. When that happens, what will be lost?

Leah McLaren

McLaren is evidently a few years older than me, as I've been online since I was about 15. However, I definitely reflect on a regular basis about what being hyper-connected does to my sense of self. She cites a recent study published in the official journal of the World Psychiatric Association. Part of the conclusion of that study reads:

As digital technologies become increasingly integrated with everyday life, the Internet is becoming highly proficient at capturing our attention, while producing a global shift in how people gather information, and connect with one another. In this review, we found emerging support for several hypotheses regarding the pathways through which the Internet is influencing our brains and cognitive processes, particularly with regards to: a) the multi‐faceted stream of incoming information encouraging us to engage in attentional‐switching and “multi‐tasking” , rather than sustained focus; b) the ubiquitous and rapid access to online factual information outcompeting previous transactive systems, and potentially even internal memory processes; c) the online social world paralleling “real world” cognitive processes, and becoming meshed with our offline sociality, introducing the possibility for the special properties of social media to impact on “real life” in unforeseen ways.

Firth, J., et al. (2019). The “online brain”: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry, 18: 119-129.

In her Guardian article, McLaren cites the main author, Dr Joseph Firth:

“The problem with the internet,” Firth explained, “is that our brains seem to quickly figure out it’s there – and outsource.” This would be fine if we could rely on the internet for information the same way we rely on, say, the British Library. But what happens when we subconsciously outsource a complex cognitive function to an unreliable online world manipulated by capitalist interests and agents of distortion? “What happens to children born in a world where transactive memory is no longer as widely exercised as a cognitive function?” he asked.

Leah McLaren

I think this is the problem, isn't it? I've got no issue with having an 'outboard brain' where I store things that I want to look up instead of remember. It's also insanely useful to have a method by which the world can join together in a form of 'hive mind'.

What is problematic is when this 'hive mind' (in the form of social media) is controlled by people and organisations whose interests are orthogonal to our own.

In that situation, there are three things we can do. The first is to seek out forms of nascent 'hive mind'-like spaces which are not controlled by people focused on the problematic concept of 'shareholder value'. Like Mastodon, for example, and other decentralised social networks.

The second is to spend time finding out the voices to which you want to pay particular attention. The chances are that they won't only write down their thoughts via social networks. They are likely to have newsletters, blogs, and even podcasts.

Third, an apologies for the metaphor, but with such massive information consumption the chances are that we can become 'constipated'. So if we don't want that to happen, if we don't want to go on an 'information diet', then we need to ensure a better throughput. One of the best things I've done is have a disciplined approach to writing (here on Thought Shrapnel, and elsewhere) about the things I've read and found interesting. That's one way to extract the nutrients.

I'd love your thoughts on this. Do you agree with the above? What strategies do you have in place?

The best way out is always through

So said Robert Frost, but I want to begin with the ending of a magnificent post from Kate Bowles. She expresses clearly how I feel sometimes when I sit down to write something for Thought Shrapnel:

[T]his morning I blocked out time, cleared space, and sat down to write — and nothing happened. Nothing. Not a word, not even a wisp of an idea. After enough time staring at the blankness of the screen I couldn’t clearly remember having had an idea, ever.

Along the way I looked at the sky, I ate a mandarin and then a second mandarin, I made a cup of tea, I watched a family of wrens outside my window, I panicked. I let email divert me, and then remembered that was the opposite of the plan. I stayed off Twitter. Panic increased.

Then I did the one thing that absolutely makes a difference to me. I asked for help. I said “I write so many stupid words in my bullshit writing job that I can no longer write and that is the end of that.” And the person I reached out to said very calmly “Why not write about the thing you’re thinking about?”

Sometimes what you have to do as a writer is sit in place long enough, and sometimes you have to ask for help. Whatever works for you, is what works.

Kate Bowles

There are so many things wrong with the world right now, that sometimes I feel like I could stop working on all of the things I'm working on and spend time just pointing them out to people.

But to what end? You don't change the world by just making people aware of things, not usually. For example, as tragic as the sentence, "the Amazon is on fire" is, it isn't in and of itself a call-to-action. These days, people argue about the facts themselves as well as the appropriate response.

The world is an inordinately complicated place that we seek to make sense of by not thinking as much as humanly possible. To aid and abet us in this task, we divide ourselves, either consciously or unconsciously, into groups who apply similar heuristics. The new (information) is then assimilated into the old (worldview).

I have no privileged position, no objective viewpoint in which to observe and judge the world's actions. None of us do. I'm as complicit in joining and forming in and out groups as the next person. I decide I'm going to delete my Twitter account and then end up rage-tweeting All The Things.

Thankfully, there are smart people, and not only academics, thinking about all this to figure out what we can and should do. Tim Urban, from the phenomenally-successful Wait But Why, for example, has spent the last three years working on "a new language we can use to think and talk about our societies and the people inside of them". In the first chapter in a new series, he writes about the ongoing struggle between (what he calls) the 'Primitive Minds' and 'Higher Minds' of humans:

The never-ending struggle between these two minds is the human condition. It’s the backdrop of everything that has ever happened in the human world, and everything that happens today. It’s the story of our times because it’s the story of all human times.

Tim Urban

I think this is worth remembering when we spend time on social networks. And especially when we spend so much time that it becomes our default delivery method for the news of the day. Our Primitive Minds respond strongly to stimuli around fear and fornication.

When we reflect on our social media usage and the changing information landscape, the temptation is either to cut down, or to try a different information diet. Some people become the equivalent of Information Vegans, attempting to source the 'cleanest' morsels of information from the most wholesome, trusted, and traceable of places.

But where are those 'trusted places' these days? Are we as happy with the previously gold-standard news outlets such as the BBC and The New York Times as we once were? And if not, what's changed?

The difference, I think, is the way we've decided to allow money to flow through our digital lives. Commercial news outlets, including those with which the BBC competes, are funded by advertising. Those adverts we see in digital spaces aren't just showing things that we might happen to be interested in. They'll keep on showing you that pair of shoes you almost bought last week in every space that is funded by advertising. Which is basically everywhere.

I feel like I'm saying obvious things here that everyone knows, but perhaps it bears repeating. If everyone is consuming news via social networks, and those news stories are funded by advertising, then the nature of what counts as 'news' starts to evolve. What gets the most engagement? How are headlines formed now, compared with a decade ago?

It's as if something hot-wires our brain when something non-threatening and potentially interesting is made available to us 'for free'. We never get to the stuff that we'd like to think defines us, because we caught in neverending cycles of titillation. We pay with our attention, that scarce and valuable resource.

Our attention, and more specifically, how we react to our social media feeds when we're 'engaged' is valuable because it can be packaged up and sold to advertisers. But it's also sold to governments too. Twitter just had to update their terms and conditions specifically because of the outcry over the Chinese government's propaganda around the Hong Kong protests.

Protesters part of the 'umbrella revolution' in Hong Kong have recently been focusing on cutting down what we used to call CCTV cameras, but which are much more accurately described as 'facial recognition masts':

We are living in a world where the answer to everything seems to be 'increased surveillance'. Kids not learning fast enough in school? Track them more. Scared of terrorism? Add more surveillance into the lives of everyday citizens. And on and on.

In an essay earlier this year, Maciej Cegłowski riffed on all of this, reflecting on what he calls 'ambient privacy':