- Reactionary neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, within an exclusionary vision of a racist, patriarchal, and homophobic society.

- Progressive neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, while using the banner of 'diversity' to assimilate equality and meritocracy.

- ‘Nation as a service’ is the ultimate goal for digitized governments (TNW) — "Right now in Estonia, when you have a baby, you automatically get child benefits. The user doesn’t have to do anything because the government already has all the data to make sure the citizen receives the benefits they’re entitled to."

- The ethics of smart cities (RTE) — "With ethics-washing, a performative ethics is being practised designed to give the impression that an issue is being taken seriously and meaningful action is occurring, when the real ambition is to avoid formal regulation and legal mechanisms."

- Cities as learning platforms (Harold Jarche) — "For the past century we have compartmentalized the life of the citizen. At work, the citizen is an ‘employee’. Outside the office he may be a ‘consumer’. Sometimes she is referred to as a ‘taxpayer’. All of these are constraining labels, ignoring the full spectrum of citizenship.

There are persons who, when they cease to shock us, cease to interest us

It's difficult not to say "I told you so" when things play out exactly as predicted. Four years ago, when Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th President of the USA, many had ominous forebodings.

Donald Trump’s inaugural address was a declaration of war on everything represented by these choreographed civilities. President Trump – it’s time to begin to get used to those jarringly ill-fitting words – did not conjure a deathless phrase for the day. His words will not lodge in the brain in any of the various uplifting ways that the likes of Lincoln, Roosevelt, Kennedy or Reagan once achieved. But the new president’s message could not have been clearer. He came to shatter the veneer of unity and continuity represented by the peaceful handover. And he may have succeeded. In 1933, Roosevelt challenged the world to overcome fear. In 2017, Mr Trump told the world to be very afraid.

The Guardian view on Donald Trump’s inauguration: a declaration of political war (January 2017)

He was all bluster, we were told. That it was rhetoric and would never be followed up with action.

Leaders are judged by their first 100 days in office. Wikipedia has a page outlining what Trump did during his, including things that, looking back from the vantage point of 2021, seem like warning shots: rolling back gun control legislation, stoking fears around voter fraud, cracking down on illegal immigration, freezing federal job hiring (except military), and engaging in tax reform to the benefit of the rich.

As a History teacher, it always struck me as odd that Adolf Hitler, a man born in Austria with brown hair, managed to lead a fascist party that extolled the virtues of being German and having blond hair. These days, I'm equally baffled that some of the richest people in our society — Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees-Mogg — can pass themselves off as 'anti-elite'.

Much of their ability to do so is by creating an alternative reality with the aid of social networks like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. These replace traditional gatekeepers to information with algorithms tweaked for engagement, attention, and profit.

As we know, whipping up hatred and peddling conspiracy theories puts these algorithms into overdrive, and ensure those who agree with the content see what's shared. But this approach also reaches those who don't agree with it, by virtue of people seeking to reject and push back on it. Meanwhile, of course, the platforms rake in $$$ from advertisers.

I get the feeling that there are a great number of people who do not understand the way the world works in 2021. I am probably one of them. In fact, given how much control we've given to algorithms in recent years, perhaps no-one truly understands.

One thing for sure, though, is that banning Donald Trump from Facebook and Instagram indefinitely is too little, too late. These platforms, among with others, downplayed his and other 'alt-right' hate speech for fear of being penalised.

Pandora's Box is open. Those who realise that everything is a construct and theory-laden will control those who don't. The latter will be reduced to merely wandering around an alternative reality, like protesters in Statuary Hall, waiting to be told what to do next.

Quotation-as-title by F.H. Bradley

Neoliberalism in any guise is not the solution but the problem

Today's quotation-as-title is from Nancy Fraser, whose short book The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born in turn gets its title from a quotation from Antonio Gramsci.

It's an excellent book; quick to read, straight to the point, and it helped me to understand some of what is going on at the moment in both US and world politics.

First, let's explain terms, as it is a book that presupposes some knowledge of political philosophy. 'Neoliberalism' isn't an easy term to define, as its meaning has mutated over time, and it's usually used in a derogatory way.

There's a whole history of the term at Wikipedia, but I'll use definitions from Investopedia and The Guardian:

Neoliberalism is a policy model—bridging politics, social studies, and economics—that seeks to transfer control of economic factors to the private sector from the public sector. It tends towards free-market capitalism and away from government spending, regulation, and public ownership.

Investopedia

In short, “neoliberalism” is not simply a name for pro-market policies, or for the compromises with finance capitalism made by failing social democratic parties. It is a name for a premise that, quietly, has come to regulate all we practise and believe: that competition is the only legitimate organising principle for human activity.

Guardian

To me, it's the reason why humans go out of their way to engineer situations where people and organisations are pitted against each other to compete for 'awards', no matter how made-up or paid-for they may be. It's a way of framing society, human interactions, and reducing everything to $$$.

In that vein, the most recent issue of New Philosopher, features an essay by Warwick Smith where he uses the thought experiment of an AI 'paperclip maximiser'. This runs amok and turns the entire universe into paperclips:

I recently heard Daniel Schmachtenberger taking this thought experiment in a very interesting direction by saying that human society is already the paperclip maximiser but instead of making paperclips we're making dollars — which are primarily just zeroes and ones in bank databases. Our collective intelligence system has on overriding purpose: to turn everything into money — trees, labour, water... everything. It is also very good at learning how to learn and is extremely good at eliminating any threats.

Warwick Smith

This attempt to turn everything into money is basically the neoliberal project. What Nancy Fraser does is identify two different strains of neoliberalism, which she explains through the lenses of 'distribution' and 'recognition':

The difference between these two strands of neoliberalism, then, comes in the way that they recognise people. Note that the method of distribution remains the same:

The political universe that Trump upended was highly restrictive. It was built around the opposition between two versions of neoliberalism, distinguished chiefly on an axis of recognition. Granted, one could choose between multiculturalism and ethnonationalism. But one was stuck, either way, with financialization and deindustrialization. With the menu limited to progressive and reactionary neoliberalism, there was no force to oppose the decimation of working-class and middle-class standards of living. Antineoliberal projects were severely marginalized, if not simply excluded from the public sphere.

Nancy Fraser

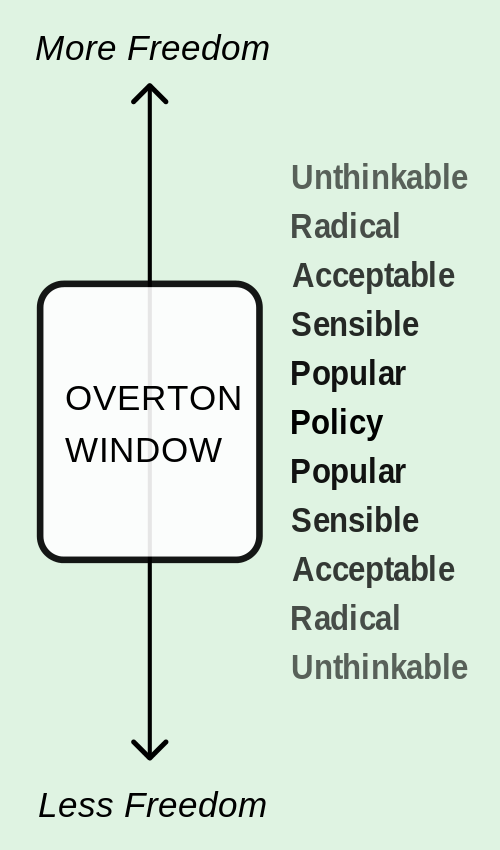

It's as if the Overton Window of acceptable public political discourse served up a menu of only different flavours of neoliberalism:

Ideologies are oriented within a narrative that spans the past, present, and future. We can argue over visions of what education should look like within a society, for example, because we're interested in how the next generation will turn out.

In Present Shock, Douglas Rushkoff explains that instead of shackling themselves to ideologies, Trump and other populist politicians take advantage of the 24/7 'always on' media landscape to provide a constant knee-jerk presentism:

A presentist mediascape may prevent the construction of false and misleading narratives by elites who mean us no good, but it also tends to leave everyone looking for direction and responding or overresponding to every bump in the road.

Douglas Rushkoff

What we're witnessing is essentially the end of politics as we know it, says Rushkoff:

As a result, what used to be called statecraft devolves into a constant struggle with crisis management. Leaders cannot get on top of issues, much less ahead of them, as they instead seek merely to respond to the emerging chaos in a way that makes them look authoritative.

[...]

If we have no destination toward we are progressing, then the only thing that motivates our movement is to get away from something threatening. We move from problem to problem, avoiding calamity as best we can, our worldview increasingly characterized by a sense of panic.

[...]

Blatant shock is the only surefire strategy for gaining viewers in the now.

Douglas Rushkoff

We might be witnessing the end of progressive neoliberalism, but it's not as if that's being replaced by anything different, anything better.

What, then, can we expect in the near term? Absent a secure hegemony, we face an unstable interregnum and the continuation of the political crisis. In this situation, the words of Gramsci ring true: "The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear."

Nancy Fraser

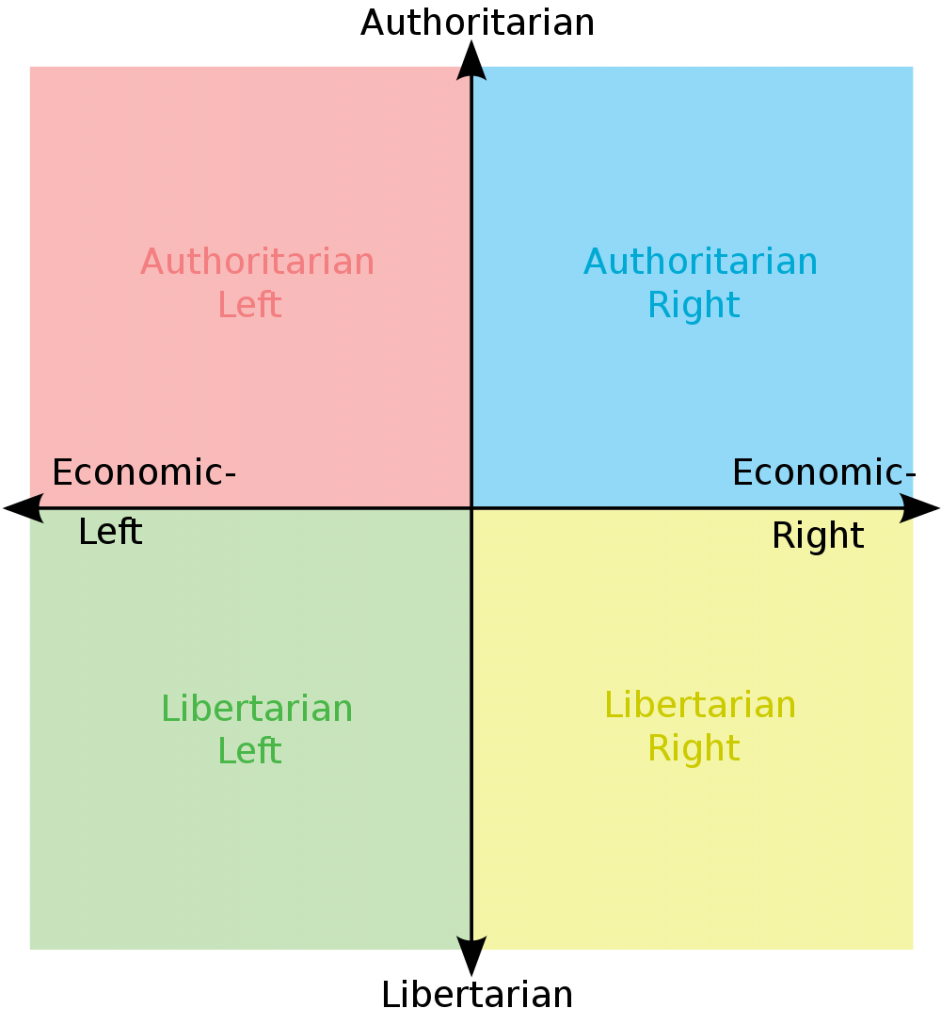

No matter what the question is, neoliberalism is never the answer. The trouble, I think, is that two-dimensional diagrams of political options are far too simplistic:

For example, as Edurne Scott Loinaz shows, even within the Libertarian Left (the 'lower left') there are many different positions:

The Libertarian Left has perhaps the best to offer in terms of fighting neoliberalism and populists like Trump. The problem is unity, and use of language:

When binary language is used within the lower left it does untold violence to our communities and makes solidarity impossible: if one can switch between binary language to speak truth about capitalists and authoritarians, and switch to dimensional language within the zone of solidarity with fellow lower leftists, it will be easier to nurture solidarity within the lower left.

Edurne Scott Loinaz

For the first time in my life, I'm actually somewhat fearful of what comes next, politically speaking. Are we going to end up with populists entrenching the authoritarian right, going back full circle to reactionary neoliberalism? Or does this current crisis mean that something new can emerge?

Header image by Guillaume Paumier used under a Creative Commons license

Form is the possibility of structure

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein with today's quotation-as-title. I'm using it as a way in to discuss some things around city planning, and in particular an article I've been meaning to discuss for what seems like ages.

In an article for The LA Times, Jessica Roy highlights a phenomenon I wish I could take back and show my 12 year-old self:

Thirty years ago, Maxis released “SimCity” for Mac and Amiga. It was succeeded by “SimCity 2000” in 1993, “SimCity 3000” in 1999, “SimCity 4” in 2003, a version for the Nintendo DS in 2007, “SimCity: BuildIt” in 2013 and an app launched in 2014.

Along the way, the games have introduced millions of players to the joys and frustrations of zoning, street grids and infrastructure funding — and influenced a generation of people who plan cities for a living. For many urban and transit planners, architects, government officials and activists, “SimCity” was their first taste of running a city. It was the first time they realized that neighborhoods, towns and cities were things that were planned, and that it was someone's job to decide where streets, schools, bus stops and stores were supposed to go.

Jessica Roy

Some games are just awesome. SimCity is still popular now on touchscreen devices, and my kids play it occasionally. It's interesting to read in the article how different people, now responsible for real cities, played the game, for example Roy quotes the Vice President of Transportation and Housing at the non-profit Silicon Valley Leadership Group

"I was not one of the players who enjoyed Godzilla running through your city and destroying it. I enjoyed making my city run well."

Jason Baker

I, on the other hand, particularly enjoyed booting up 'scenario mode' where you had to rescue a city that had been ravaged by Godzilla, aliens, or a natural disaster.

This isn't an article about nostalgia, though, and if you read the article in more depth you realise that it's an interesting insight into our psychology around governance of cities and nations. For example, going back to an article from 2018 that also references SimCity, Devon Zuegel writes:

The way we live is shaped by our infrastructure — the public spaces, building codes, and utilities that serve a city or region. It can act as the foundation for thriving communities, but it can also establish unhealthy patterns when designed poorly.

[...]

People choose to drive despite its costs because they lack reasonable alternatives. Unfortunately, this isn’t an accident of history. Our transportation system has been overly focused on automobile traffic flow as its metric of success. This single-minded focus has come at the cost of infrastructure that supports alternative ways to travel. Traffic flow should, instead, be one goal out of many. Communities would be far healthier if our infrastructure actively encouraged walking, cycling, and other forms of transportation rather than subsidizing driving and ignoring alternatives.

Devon Zuegel

In other words, the decisions we ask our representatives to make have a material impact in shaping our environment. That, in turn, affects our decisions about how to live and work.

When we don't have data about what people actually do, it's easy for ideology and opinions to get in the way. That's why I'm interested in what Los Angeles is doing with its public transport system. As reported by Adam Rogers in WIRED, the city is using mobile phone data to see how it can 'reboot' its bus system. It turns out that the people running the system had completely the wrong assumptions:

In fact, Metro's whole approach turned out to be skewed to the wrong kinds of trips. “Traditionally we're trying to provide fast service for long-distance trips,” [Anurag Komanduri, a data anlyst] says. That's something the Orange Line and trains are good at. But the cell phone data showed that only 16 percent of trips in LA County were longer than 10 miles. Two-thirds of all travel was less than five miles. Short hops, not long hauls, rule the roads.

Adam Rogers

There's some discussion later in the article about the "baller move" of ripping down some of the freeways to force people to use public transportation. Perhaps that's actually what's required.

In Barcelona, for example, "fiery leftist housing activist" Ada Colau became the city's mayor in 2015. Since then, they've been doing some radical experimentation. David Roberts reports for Vox on what they've done with one area of the city that I've actually seen with my own eyes:

Inside the superblock in the Poblenou neighborhood, in the middle of what used to be an intersection, there’s a small playground, with a set of about a dozen picnic tables next to it, just outside a local cafe. On an early October evening, neighbors sit and sip drinks to the sound of children’s shouts and laughter. The sun is still out, and the warm air smells of wild grasses growing in the fresh plantings nearby.

David Roberts

I can highly recommended watching this five-minute video overview of the benefits of this approach:

So if it work, why aren't we seeing more of this? Perhaps it's because, as Simon Wren-Lewis points out on his blog, most of us are governed by incompetents:

An ideology is a collection of ideas that can form a political imperative that overrides evidence. Indeed most right wing think tanks are designed to turn the ideology of neoliberalism into policy based evidence. It was this ideology that led to austerity, the failed health reforms and the privatisation of the probation service. It also played a role in Brexit, with many of its protagonists dreaming of a UK free from regulations on workers rights and the environment. It is why most of the recent examples of incompetence come from the political right.

Simon Wren-Lewis

A pluralist democracy has checks and balances in part to guard against incompetence by a government or ministers. That is one reason why Trump and the Brexiters so often attack elements of a pluralist democracy. The ultimate check on incompetence should be democracy itself: incompetent politicians are thrown out. But when a large part of the media encourage rather than expose acts of incompetence, and the non-partisan media treat knowledge as just another opinion, that safegurd against persistent incompetence is put in danger.

We seem to have started with SimCity and ended with Trump and Brexit. Sorry about that, but without decent government, we can't hope to improve our communities and environment.

Also check out:

Facebook is an instrument of the state

This should not surprise us:

Facebook now seems to be explicitly admitting that it also intends to follow the censorship orders of the U.S. government.Many people get the majority of their news through Facebook, so censorship isn't just banning someone from a scoail network, it has an impact on the social and democratic life of nation states:

What this means is obvious: that the U.S. government — meaning, at the moment, the Trump administration — has the unilateral and unchecked power to force the removal of anyone it wants from Facebook and Instagram by simply including them on a sanctions list. Does anyone think this is a good outcome? Does anyone trust the Trump administration — or any other government — to compel social media platforms to delete and block anyone it wants to be silenced?Source: The Intercept

Does it take Trump to make badges go mainstream?

Perversely, it might take something like the Trump administration to make Open Badges work at scale. Why? Because Republicans don’t trust Higher Education:

Is support for higher ed fragmenting along political lines? It is if you believe the recent Pew poll showing Republicans’ distrust of higher ed is growing relative to Democrats (on a nearly 2-to-1 margin) is not fake news... In any case, look for Trump’s Department of Education to push on the trend toward more “practical” vocational learning and not just apprenticeships. Higher Ed Act proposals this year may push to open up federal financial aid beyond the credit-hour.Things, of course, are different in the US to the rest of the world. In Europe I think we've always had a different, and more positive, relationship to vocational education.

Source: Education Design Lab