- Payments: Mastercard, PayPal, PayU (Naspers’ fintech arm), Stripe, Visa

- Technology and marketplaces: Booking Holdings, eBay, Facebook/Calibra, Farfetch, Lyft, MercadoPago, Spotify AB, Uber Technologies, Inc.

- Telecommunications: Iliad, Vodafone Group

Blockchain: Anchorage, Bison Trails, Coinbase, Inc., Xapo Holdings Limited - Venture Capital: Andreessen Horowitz, Breakthrough Initiatives, Ribbit Capital, Thrive Capital, UnionSquare Ventures

- Nonprofit and multilateral organizations, and academic institutions: Creative Destruction Lab, Kiva,Mercy Corps, Women’s World Banking

- Facebook's Libra could threaten the global financial system (Sky News) — "it's effectively reinvented PayPal, only with Facebook Pounds instead of regular ones."

- Why We’re Joining the Libra Association (Spotify) — "One challenge for Spotify and its users around the world has been the lack of easily accessible payment systems."

- The real risk of Facebook’s Libra coin is crooked developers (TechCrunch) — "A shady developer could build a wallet that just cleans out a user’s account or funnels their coins to the wrong recipient, mines their purchase history for marketing data or uses them to launder money. Digital risks become a lot less abstract when real-world assets are at stake."

- Degrowth: a Call for Radical Abundance (Jason Hickel) — "In other words, the birth of capitalism required the creation of scarcity. The constant creation of scarcity is the engine of the juggernaut."

- Hey, You Left Something Out (Cogito, Ergo Sumana) — "People who want to compliment work should probably learn to give compliments that sound encouraging."

- The Problem is Capitalism (George Monbiot) — "A system based on perpetual growth cannot function without peripheries and externalities. There must always be an extraction zone, from which materials are taken without full payment, and a disposal zone, where costs are dumped in the form of waste and pollution."

- In Stores, Secret Surveillance Tracks Your Every Move (The New York Times) — "For years, Apple and Google have allowed companies to bury surveillance features inside the apps offered in their app stores. And both companies conduct their own beacon surveillance through iOS and Android."

- The Inevitable Same-ification of the Internet

(Matthew Ström) — "Convergence is not the sign of a broken system, or a symptom of a more insidious disease. It is an emergent phenomenon that arises from a few simple rules." - There is nothing more depressing than “positive news” (The Outline) — "The world is often a bummer, but a whole ecosystem of podcasts and Facebook pages have sprung up to assure you that things are actually great."

- Space for More Spaces (CogDogBlog) — "I still hold on to the idea that those old archaic, pre-social media constructs, a personal blog, is the main place, the home, to operate from."

- Clay Shirky on Mega-Universities and Scale (Phil on EdTech) — "What the mega-university story gets right is that online education is transforming higher education. What it gets wrong is the belief that transformation must end with consolidation around a few large-scale institutions"

- What do cats do all day? (The Kid Should See This) — "Catcam footage from collar cameras captured the activities of 16 free-roaming domestic cats in England as they explored, stared, touched noses, hunted, vocalized, and more."

- These researchers invented an entirely new way of building with wood (Fast Company) — "Each of the 12 wooden components of the tower was made by laminating two pieces of wood with different levels of moisture. Then, when the laminated pieces of wood dried out, the piece of wood curved naturally–no molds or braces needed."

- What Did Old English Sound Like? Hear Reconstructions of Beowulf, The Bible, and Casual Conversations (Open Culture) — "Over the course of 1000 years, the language came together from extensive contact with Anglo-Norman, a dialect of French; then became heavily Latinized and full of Greek roots and endings; then absorbed words from Arabic, Spanish, and dozens of other languages, and with them, arguably, absorbed concepts and pictures of the world that cannot be separated from the language itself."

- Adversarial interoperability: reviving an elegant weapon from a more civilized age to slay today's monopolies (BoingBoing) — "This kind of adversarial interoperability goes beyond the sort of thing envisioned by "data portability," which usually refers to tools that allow users to make a one-off export of all their data, which they can take with them to rival services. Data portability is important, but it is no substitute for the ability to have ongoing access to a service that you're in the process of migrating away from."

- Fables of School Reform (The Baffler) — "Even pre-internet efforts to upgrade the technological prowess of American schools came swathed in the quasi-millennial promise of complete school transformation."

- Celebrate your wins

- Address your losses or weaknesses

- Note your "coulda, woulda, shoulda" tasks

- Create goals for next week

- Summarise it all in one sentence

- Trying (Snakes and Ladders) — "I realized that one of the reasons I like doing the newsletter so much is that I have (quite unconsciously) understood it as a place not to do analysis or critique but to share things that give me delight."

- 43 — All in & with the flow (Buster Benson) — "It’s tempting to always rationalize why our current position is optimal, but as I get older it’s a lot easier to see how things move in cycles, and the cycles themselves are what we should pay attention to more than where we happen to be in them at the moment.

- Four Ways to Figure Out What You Really Want to Do with Your Life (Lifehacker) — "In the end, figuring out your passion, your career path, your life purpose—whatever you want to call it—isn’t an easy process and no magic bullet exists for doing it."

- "Inequality encourages the rich to invest not innovation but in... means of entrenching their privilege and power"

- "Unequal corporate hierarchies can demotivate junior employees"

- "Economic inequality leads to less trust"

- "Inequality can prevent productivity-enhancing change"

- "Inequality can cause the rich to be fearful of future redistribution or nationalization, which will make them loath to invest"

- "Inequalities of power... have allowed governments to abandon the aim of truly full employment and given firms more ability to boost profits by suppressing wages and conditions [which] has disincentivized investments in labour-saving technologies"

- "High-powered incentives that generate inequality within companies can backfire... [as] they encourage bosses to hit measured targets and neglect less measurable things"

- "High management pay can entrench... the 'forces of conservatism' which are antagonistic to technical progress"

- Why High-Class People Get Away With Incompetence (The New York Times) — "Even researchers who specialize in social class struggle to agree on the weight to give income, family wealth, professional prestige and other factors."

- “Is it unethical to not tell my employer I’ve automated my job?” (Fast Company) — "The fear that people are disposable if their productivity can be bested by technology may lead to a confidence of trust as well as unpleasant and unintended consequences."

- Should You Tell the World How Much Money You Make? (The New York Times) — Secrecy is one reason accurate salary data is hard to find. It also benefits companies if employees underestimate their value."

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion.

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job.

- Reduced professional efficacy.

- Your Kids Think You’re Addicted to Your Phone (The New York Times) — "Most parents worry that their kids are addicted to the devices, but about four in 10 teenagers have the same concern about their parents."

- Why the truth about our sugar intake isn't as bad as we are told (New Scientist) — "In fact, the UK government 'Family food datasets', which have detailed UK household food and drink expenditure since 1974, show there has been a 79 per cent decline in the use of sugar since 1974 – not just of table sugar, but also jams, syrups and honey."

- Can We Live Longer But Stay Younger? (The New Yorker) — "Where fifty years ago it was taken for granted that the problem of age was a problem of the inevitable running down of everything, entropy working its worst, now many researchers are inclined to think that the problem is “epigenetic”: it’s a problem in reading the information—the genetic code—in the cells."

- MIT Starts University Group to Build New Digital Credential System (EdSurge) — "The group... expects the standard to be “completely complementary” to the Open Badges standard that has been in the works for many years."

- European MOOC Consortium launches Common Micro-credential Framework (Education Technology) — "A leading driver for the development of the framework is the demand from learners to develop new knowledge, skills and competencies from shorter, recognised and quality-assured courses."

- Why a New Kind of ‘Badge’ Stands Out From the Crowd (The Chronicle of Higher Education) — "As we’ve been reporting, the buzz around certificates, badges, and other measures of achievement has been on the rise as employers have increasingly questioned whether a college degree is a reliable or adequate “signal” of an applicant’s capabilities."

- Apple created the privacy dystopia it wants to save you from (Fast Company) — I'm not sure I agree with either the title or subtitle of this piece, but it raises some important points.

- When Grown-Ups Get Caught in Teens’ AirDrop Crossfire (The Atlantic) — hilarious and informative in equal measure!

- Anxiety, revolution, kidnapping: therapy secrets from across the world (The Guardian) — a fascinating look at the reasons why people in different countries get therapy.

- Post-it note war over flowers deemed ‘most middle-class argument ever’ (Metro) — amusing, but there's important things to learn from this about private/public spaces.

- Modern shamans: Financial managers, political pundits and others who help tame life’s uncertainty (The Conversation) — a 'cognitive anthropologist' explains the role of shamans in ancient societies, and extends the notion to the modern world.

- The guy who made a tool to track women in porn videos is sorry (MIT Technology Review) — "Under GDPR, personal data (and especially sensitive biometric data) needs to be collected for specific and legitimate purposes. Scraping data to figure out if someone once appeared in porn is not that."

- ‘The Next Backlash Is Going to Be Against Technology’ (Foreign Policy) — "We’ve seen the backlash against globalization. If anything, the dislocations and the adverse labor market implications of artificial intelligence, automation, new digital technologies—the impacts of those will be even larger."

- MIT AI model is 'significantly' better at predicting breast cancer (Engadget) — "AI has potential to help fix the racial disparity in women's healthcare as well. Since current guidelines for breast cancer are based on primarily white populations, this can lead to delayed detection among women of color."

- A New York School District Will Test Facial Recognition System On Students Even Though The State Asked It To Wait (BuzzFeed News) — "Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has expressed concern in a congressional hearing on the technology last week that facial recognition could be used as a form of social control."

- Amazon preparing a wearable that ‘reads human emotions,’ says report (The Verge) — "This is definitely one of those things that hasn’t yet been done because of how hard it is to do."

- Google’s Sundar Pichai: Privacy Should Not Be a Luxury Good (The New York Times) — "Ideally, privacy legislation would require all businesses to accept responsibility for the impact of their data processing in a way that creates consistent and universal protections for individuals and society as a whole.

- One step ahead: how walking opens new horizons (The Guardian) — "Walking provides just enough diversion to occupy the conscious mind, but sets our subconscious free to roam. Trivial thoughts mingle with important ones, memories sharpen, ideas and insights drift to the surface."

- A Philosophy of Walking (Frédéric Gros) — "a bestseller in France, leading thinker Frédéric Gros charts the many different ways we get from A to B—the pilgrimage, the promenade, the protest march, the nature ramble—and reveals what they say about us."

- What 10,000 Steps Will Really Get You (The Atlantic) — "While basic guidelines can be helpful when they’re accurate, human health is far too complicated to be reduced to a long chain of numerical imperatives. For some people, these rules can even do more harm than good."

- Is High Quality Software Worth the Cost? (Martin Fowler) — "I thus divide software quality attributes into external (such as the UI and defects) and internal (architecture). The distinction is that users and customers can see what makes a software product have high external quality, but cannot tell the difference between higher or lower internal quality."

- What the internet knows about you (Axios) — "The big picture: Finding personal information online is relatively easy; removing all of it is nearly impossible."

- Against Waldenponding II (ribbonfarm) — "Waldenponding is a search for meaning that is circumscribed by the what you might call the spiritual gravity field of an object or behavior held up as ineffably sacred. "

- Britain's equivalent to Tutankhamun found in Southend-on-Sea (The Guardian) — "Gold foil crosses were found in the grave which indicate he was a Christian, a fact which has also surprised historians."

- Writer James Vlahos explains how voice computing will change the way we live (The Verge) — "If you’re only presenting one answer, it better not be junk. I think the conversation is going to more turn toward censorship. Why do they get to choose what is deemed to be fact?"

- Prisoner’s dilemma shows exploitation is a basic property of human society (MIT Technology Review) — "The next question this kind of work must answer is how exploitation can be avoided or what strategy exploited individuals must use to change their lot."

- What Can Video Games Teach Us About Instructional Design? (John Spencer) — "The best video games provide instant feedback. Players know where they have been, where they are, and where they are going. They don’t have to stop what they are doing in order to see their progress."

- It's Getting Way Too Easy to Create Fake Videos of People's Faces (Vice) — "Instead of teaching the algorithm to paste one face onto another using a catalogue of expressions from one person, they use the facial features that are common across most humans to then puppeteer a new face."

- A parent's guide to raising a good digital citizen (Engadget) — "How do kids learn digital citizenship? The same way they learn how to be good citizens: They watch good role models, and they practice."

- Can "Indie" Social Media Save Us? (The New Yorker) — "When you confine your online activities to so-called walled-garden networks, you end up using interfaces that benefit the owners of those networks."

- I was wrong about networks (George Siemens) — "I'll hold to my mantra that it's networks all the way down. I need to add a critical caveat: all connections and networks occur within a system."

- Add widget after comment — allows me to add automatically after a post anything I'd usually add to a sidebar. I use it to encourage people to become supporters.

- MailPoet — I use this to automatically send out each post to supporters and to curate the weekly round-up to both supporters and subscribers.

- tao-schedule-update — means I can schedule updates to already published posts, changing categories, visibility, etc.

- Is pleasure all that is good about experience? (Journal of Philosophical Studies) — "In this article I present the claim that hedonism is not the most plausible experientialist account of wellbeing. The value of experience should not be understood as being limited to pleasure, and as such, the most plausible experientialist account of wellbeing is pluralistic, not hedonistic."

- Strong Opinions Loosely Held Might be the Worst Idea in Tech (The Glowforge Blog) — "What really happens? The loudest, most bombastic engineer states their case with certainty, and that shuts down discussion. Other people either assume the loudmouth knows best, or don’t want to stick out their neck and risk criticism and shame. This is especially true if the loudmouth is senior, or there is any other power differential."

- Why Play a Music CD? ‘No Ads, No Privacy Terrors, No Algorithms’ (The New York Times) — "What formerly hyped, supposedly essential technology has since been exposed for gross privacy violations, or for how easily it has become a tool for predatory disinformation?"

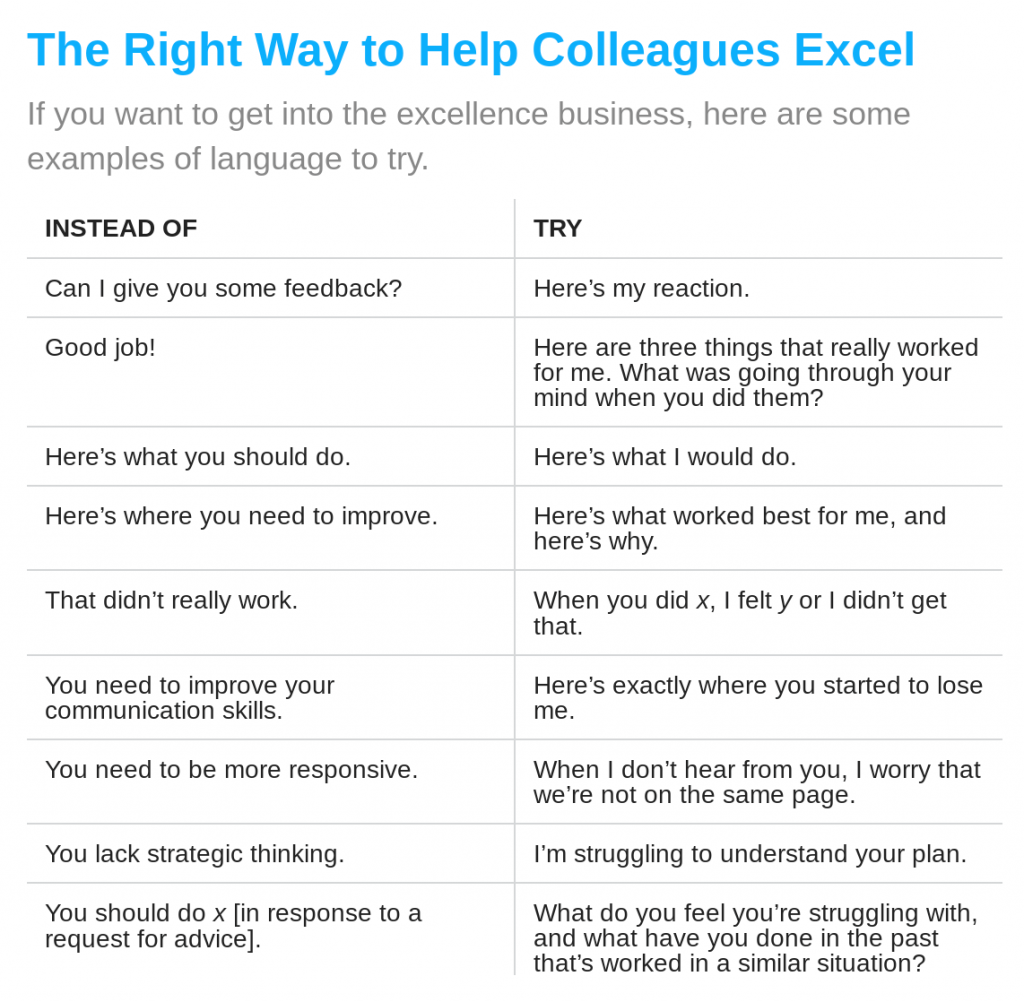

- Other people are more aware than you are of your weaknesses

- You lack certain abilities you need to acquire, so your colleagues should teach them to you

- Great performance is universal, analyzable, and describable, and that once defined, it can be transferred from one person to another, regardless of who each individual is

- Iris Murdoch, The Art of Fiction No. 117 (The Paris Review) — "I would abominate the idea of putting real people into a novel, not only because I think it’s morally questionable, but also because I think it would be terribly dull."

- How an 18th-Century Philosopher Helped Solve My Midlife Crisis (The Atlantic) — "I had found my salvation in the sheer endless curiosity of the human mind—and the sheer endless variety of human experience."

- A brief history of almost everything in five minutes (Aeon) —According to [the artist], the piece ‘is intended for both introspection and self-reflection, as a mirror to ourselves, our own mind and how we make sense of what we see; and also as a window into the mind of the machine, as it tries to make sense of its observations and memories’.

- Why Do You Grab Your Bag When Running Off a Burning Plane? (The New York Times) — it turns out that it's less of a decision, more of an impulse.

- If a house was designed by machine, how would it look? (BBC Business) — lighter, more efficient buildings.

- Playdate is an adorable handheld with games from the creators of Qwop, Katamari, and more (The Verge) — a handheld console with a hand crank that's actually used for gameplay instead of charging!

- The true story of the worst video game in history (Engadget) — it was so bad they buried millions of unsold cartridges in the desert.

- E Ink Smartphones are the big new trend of 2019 (Good e-Reader) — I've actually also own a regular phone with an e-ink display, so I can't wait for this to be a thing.

- Are we on the road to civilisation collapse? (BBC Future) — "Collapse is often quick and greatness provides no immunity. The Roman Empire covered 4.4 million sq km (1.9 million sq miles) in 390. Five years later, it had plummeted to 2 million sq km (770,000 sq miles). By 476, the empire’s reach was zero."

- Fish farming could be the center of a future food system (Fast Company) — "Aquaculture has been shown to have 10% of the greenhouse gas emissions of beef when it’s done well, and 50% of the feed usage per unit of production as beef"

- The global internet is disintegrating. What comes next? (BBC FutureNow) — "A separate internet for some, Facebook-mediated sovereignty for others: whether the information borders are drawn up by individual countries, coalitions, or global internet platforms, one thing is clear – the open internet that its early creators dreamed of is already gone."

The habit of sardonic contemplation is the hardest habit of all to break

Angela Carter with the story of my life there. I can't help but be skeptical about 'Libra', Facebook's new crytocurrency project. I'm skeptical about almost all cryptocurrencies, to be honest.

The website is marketing. It's all about 'empowering' the 'unbanked' worldwide. However, let's dive into the white paper:

Members of the Libra Association will consist of geographically distributed and diverse businesses, nonprofit and multilateral organizations, and academic institutions. The initial group of organizations that will work together on finalizing the association’s charter and become “Founding Members” upon its completion are, by industry:

We hope to have approximately 100 members of the Libra Association by the target launch in the first half of 2020.

So, all the usual suspects. How will Facebook ensure that we don't see the crazy price volatility we've seen with other cryptocurrencies?

Libra is designed to be a stable digital cryptocurrency that will be fully backed by a reserve of real assets — the Libra Reserve — and supported by a competitive network of exchanges buying and selling Libra. That means anyone with Libra has a high degree of assurance they can convert their digital currency into local fiat currency based on an exchange rate, just like exchanging one currency for another when traveling. This approach is similar to how other currencies were introduced in the past: to help instill trust in a new currency and gain widespread adoption during its infancy, it was guaranteed that a country’s notes could be traded in for real assets, such as gold. Instead of backing Libra with gold, though, it will be backed by a collection of low-volatility assets, such as bank deposits and short-term government securities in currencies from stable and reputable central banks.

So it sounds like all of the value is being extracted by founding members. Now let's move onto the technology. Any surprises there? Nope.

Blockchains are described as either permissioned or permissionless in relation to the ability to participate as a validator node. In a “permissioned blockchain,” access is granted to run a validator node. In a “permissionless blockchain,” anyone who meets the technical requirements can run a validator node. In that sense, Libra will start as a permissioned blockchain.

This is as conservative as they come, which is exactly what your strategy would be if you're trying to transfer the entire monetary system to one that you control. People often joke about Facebook as 'social infrastructure', but this is a level beyond. This is Facebook as financial infrastructure.

Given both current and potential future regulatory oversight, Facebook are very careful to distance themselves from Libra. In fact, the website proudly states that, "The Libra Association is an independent, not-for-profit membership organization, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland."

To be fair,Josh Constine, writing for TechCrunch, notes that Facebook only gets one vote as a founding member of the Libra Association. It does actually look like they're in it for the long-haul:

In cryptocurrencies, Facebook saw both a threat and an opportunity. They held the promise of disrupting how things are bought and sold by eliminating transaction fees common with credit cards. That comes dangerously close to Facebook’s ad business that influences what is bought and sold. If a competitor like Google or an upstart built a popular coin and could monitor the transactions, they’d learn what people buy and could muscle in on the billions spent on Facebook marketing. Meanwhile, the 1.7 billion people who lack a bank account might choose whoever offers them a financial services alternative as their online identity provider too. That’s another thing Facebook wants to be.

John Constine

Whereas before there's always been social pressure to have a Facebook account, now there could be pressures that span identity and economic necessities, too.

Some good commentary on the hurdles ahead comes from Kari Paul for The Guardian, who writes:

The company claims it will not attempt to bypass existing regulation but instead “innovate” on regulatory fronts. Libra will use the same verification and anti-fraud processes that banks and credit cards use and will implement automated systems to detect fraud, Facebook said in its launch. It also promised to give refunds to any users who are hacked or have Libra stolen from their digital wallets.

Kari Paul

Would this be the same kind of 'innovation' that Uber uses to muscle its way into cities without a license? Or to muscle its way into cities without a license? Perhaps it's the shady business practices beloved of PayPal? Both companies are founding members, after all!

Right now, developers can get access to a 'test network' for Libra. The system itself won't be running until the end of 2020, so there's a lot speculation. Here's some sources I found useful, but you'll need to make up your own mind. Is this a good thing?

To be perfectly symmetrical is to be perfectly dead

So said Igor Stravinsky. I'm a little behind on my writing, and prioritised writing up my experiences in the Lake District over the past couple of days.

Today's update is therefore a list post:

Life doesn’t depend on any one opinion, any one custom, or any one century

Baltasar Gracián was a 17th-century Spanish Jesuit who put together a book of aphorisms usually translated The Pocket Oracle and Art of Prudence or simply The Art of Worldly Wisdom. It's one of a few books that have had a very large effect on my life. Today's quotation-as-title comes from him.

The historian in me wonders about why we seem to live in such crazy times. My simple answer is 'the internet', but I want to dig into a bit using an essay from Scott Alexander:

[T]oday we have an almost unprecedented situation.

We have a lot of people... boasting of being able to tolerate everyone from every outgroup they can imagine, loving the outgroup, writing long paeans to how great the outgroup is, staying up at night fretting that somebody else might not like the outgroup enough.

This is really surprising. It’s a total reversal of everything we know about human psychology up to this point. No one did any genetic engineering. No one passed out weird glowing pills in the public schools. And yet suddenly we get an entire group of people who conspicuously promote and defend their outgroups, the outer the better.

What is going on here?

Scott Alexander

It's long, and towards the end, Alexander realises that he's perhaps guilty of the very thing he's pointing out. Nevertheless, his definition of an 'outgroup' is useful:

So what makes an outgroup? Proximity plus small differences. If you want to know who someone in former Yugoslavia hates, don’t look at the Indonesians or the Zulus or the Tibetans or anyone else distant and exotic. Find the Yugoslavian ethnicity that lives closely intermingled with them and is most conspicuously similar to them, and chances are you’ll find the one who they have eight hundred years of seething hatred toward.

Scott Alexander

Over the last three years in the UK, we've done a spectacular job of adding a hatred of the opposing side in the Brexit debate to our national underlying sense of xenophobia . What's necessary next is to bring everyone together and, whether we end up leaving the EU or not, forging a new narrative.

As Bryan Caplan points out, such efforts at cohesion need to be approached obliquely. He uses the example of American politics, but it applies equally elsewhere, including the UK:

Suppose you live in a deeply divided society: 60% of people strongly identify with Group A, and the other 40% strongly identify with Group B. While you plainly belong to Group A, you’re convinced this division is bad: It would be much better if everyone felt like they belonged to Group AB. You seek a cohesive society, where everyone feels like they’re on the same team.

What’s the best way to bring this cohesion about? Your all-too-human impulse is to loudly preach the value of cohesion. But on reflection, this is probably counter-productive. When members of Group B hear you, they’re going to take “cohesion” as a euphemism for “abandon your identity, and submit to the dominance of Group A.” None too enticing. And when members of Group A notice Group B’s recalcitrance, they’re probably going to think, “We offer Group B the olive branch of cohesion, and they spit in our faces. Typical.” Instead of forging As and Bs into one people, preaching cohesion tears them further apart.

Bryan Caplan

So, what can we do? Caplan suggests that members of one side should go out of their way to be overwhelmingly positive and friendly to the other side:

The first rule of promoting cohesion is: Don’t talk about cohesion. The second rule of promoting cohesion is: Don’t talk about cohesion. If you really want to build a harmonious, unified society, take one for the team. Discard your anger, swallow your pride, and show out-groups unilateral respect and friendship. End of story.

Bryan Caplan

It reminds me of the Christian advice to "turn the other cheek" which must have melted the brains of those listening to Jesus who were used to the Old Testament approach:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if anyone would sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well.

Matthew 5:38-40 (ESV)

Over the last 20 years, as the internet has played an ever-increasing role in our daily lives, we've seen a real ramping-up of the feminist movement, gay marriage becoming the norm in civilised western democracies, and movements like #BlackLivesMatter reminding us of just how racist our societies are.

In addition, despite the term being coined as long ago as 1989, we've seen a rise in awareness around intersectionality. It's not exactly a radical notion to say that us being more connected leads to more awareness of 'outgroups'. What is interesting is the way that we choose to deal with that.

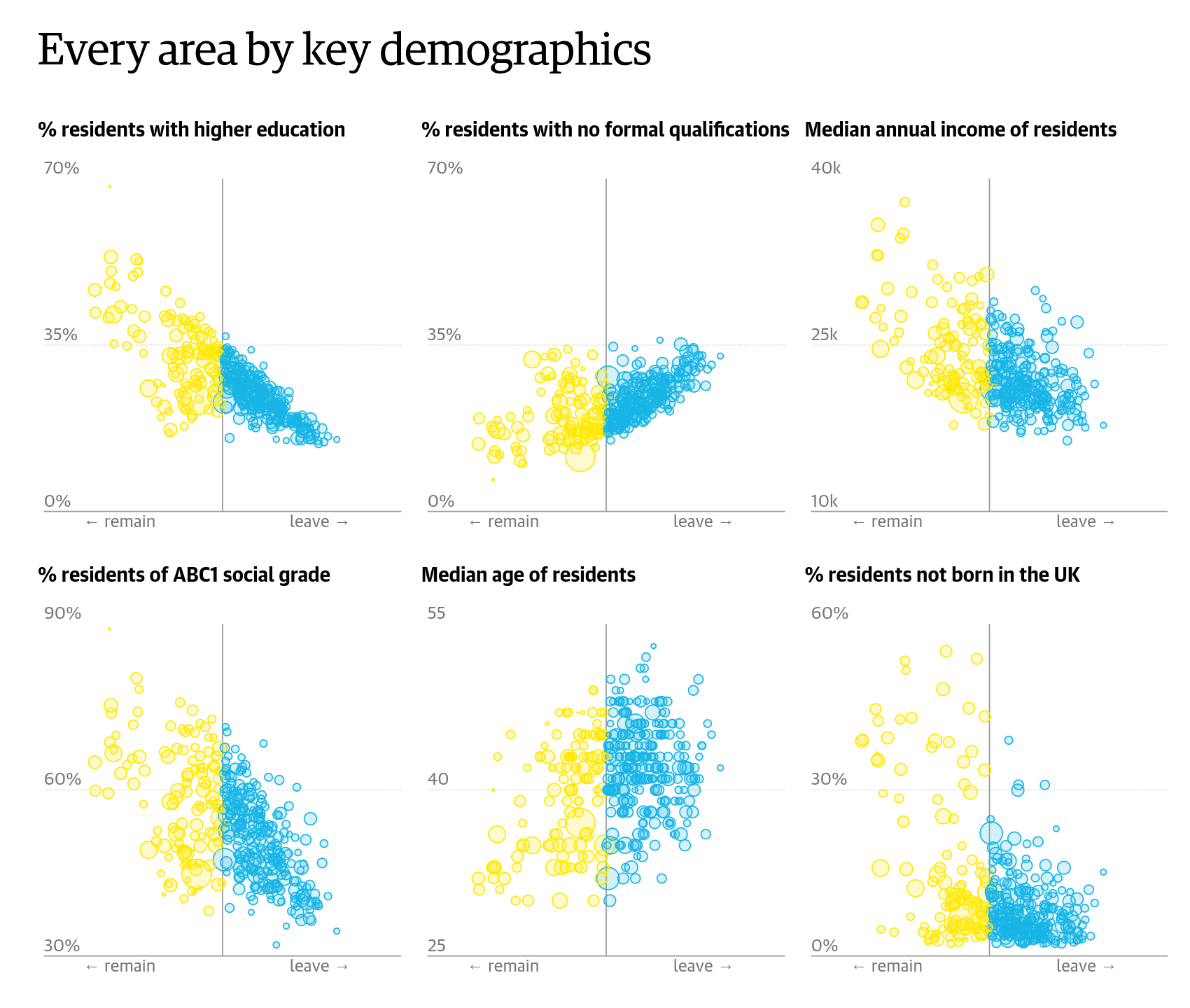

Let's have a quick look at the demographics from the Brexit vote three years ago:

Remain voters were, on the whole, younger, better educated, and more well-off than Leave voters. They were also slightly more likely to be born outside the UK. I haven't done the research, but I just have a feeling that the generational differences here are to do with relative exposure to outgroups.

What's more interesting than the result of the referendum itself, of course, is the reaction since then, with both 'Leavers' and 'Remainers' digging in to their entrenched positions. Now we've created new outgroups, we can join together in welcoming in the old outgroups. Hence LGBT+ pride rainbows in shops and everywhere else.

As I explained five years ago, one of the problems is that we're not collectively aware enough of the role money plays in our democratic processes and information landscapes:

The problem with social networks as news platforms is that they are not neutral spaces. Perhaps the easiest way to get quickly to the nub of the issue is to ask how they are funded. The answer is clear and unequivocal: through advertising. The two biggest social networks, Twitter and Facebook (which also owns Instagram and WhatsApp), are effectively “services with shareholders.” Your interactions with other people, with media, and with adverts, are what provide shareholder value. Lest we forget, CEOs of publicly-listed companies have a legal obligation to provide shareholder value. In an advertising-fueled online world this means continually increasing the number of eyeballs looking at (and fingers clicking on) content.

Doug Belshaw

Sadly, in the west we invested in Computing to the detriment of critical digital literacies at exactly the wrong moment. That investment should have come on top of a real push to help everyone in society realise the importance of questioning and reflecting on their information environment.

Much as some people might like to, we can't put the internet back in a box. It's connected us all, for better and for worse, in ways that only a few would have foreseen. It's changing the way we interact with one another, the way we buy things, and the way we think about education, work, and human flourishing.

All these connections might mean that style of representative democracy we're currently used to might need tweaking. As Jamie Bartlett points out in The People vs Tech, "these are spiritual as well as technical questions".

Also check out:

Friday feastings

These are things I came across that piqued my attention:

Even in their sleep men are at work

For today's title I've used Marcus Aurelius' more concise, if unfortunately gendered, paraphrasing of a slightly longer quotation from Heraclitus. It's particularly relevant to me at the moment, as recently I've been sleepwalking. This isn't a new thing; I've been doing it all my life when something's been bothering me.

When I tell people about this, they imagine something similar to the cartoon above. The reality is somewhat more banal, with me waking up almost as soon as I get out of bed and then getting back into it.

Sometimes I'm not entirely sure what's bothering me. Other times I do, but it's a combintion of things. In an article for Inc. Amy Morin gives some advice, explains there's an important difference between 'ruminating' and 'problem-solving':

If you're behind on your bills, thinking about how to get caught up can be helpful. But imagining yourself homeless or thinking about how unfair it is that you got behind isn't productive.

So ask yourself, "Am I ruminating or problem-solving?"

Amy Morin

If you're dwelling on the problem, you're ruminating. If you're actively looking for solutions, you're problem-solving.

Morin goes on to talk about 'changing the channel' which can be a very difficult thing to do. One thing that helps me is reading the work of Stoic philosophers such as The Enchiridion by Epictetus, which begins with some of the best advice I've ever read:

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.

The things in our control are by nature free, unrestrained, unhindered; but those not in our control are weak, slavish, restrained, belonging to others. Remember, then, that if you suppose that things which are slavish by nature are also free, and that what belongs to others is your own, then you will be hindered. You will lament, you will be disturbed, and you will find fault both with gods and men. But if you suppose that only to be your own which is your own, and what belongs to others such as it really is, then no one will ever compel you or restrain you. Further, you will find fault with no one or accuse no one. You will do nothing against your will. No one will hurt you, you will have no enemies, and you not be harmed.

Aiming therefore at such great things, remember that you must not allow yourself to be carried, even with a slight tendency, towards the attainment of lesser things. Instead, you must entirely quit some things and for the present postpone the rest. But if you would both have these great things, along with power and riches, then you will not gain even the latter, because you aim at the former too: but you will absolutely fail of the former, by which alone happiness and freedom are achieved.

Work, therefore to be able to say to every harsh appearance, "You are but an appearance, and not absolutely the thing you appear to be." And then examine it by those rules which you have, and first, and chiefly, by this: whether it concerns the things which are in our own control, or those which are not; and, if it concerns anything not in our control, be prepared to say that it is nothing to you.

Epictetus

Donald Robertson, founder of Modern Stoicism, is an author and psychotherapist. Robertson was interviewed by Knowledge@Wharton for their podcast, which they've also transcribed. He makes a similar point to Epictetus, based on the writings of Marcus Aurelius:

Ultimately, the only thing that’s really under our control is our own will, our own actions. Things happen to us, but what we can really control is the way that we respond to those things. Stoicism wants us to take also greater responsibility, greater ownership for the things that we can actually do, both in terms of our thoughts and our actions, and respond to the situations that we face.

Donald Robertson

Robertson talks in the interview about how Stoicism has helped him personally:

It’s helped me to cope with a lot of things, even relatively trivial things. The last time I went to the dentist, I’m sure I was using Stoic pain management techniques. It becomes a habitual thing. Coping with some of the stress that therapists have when they’re dealing with clients who sometimes describe very traumatic problems, and the stress of working with other people who have their difficulties and stresses. [I moved] to Canada a few years ago, and that was a big upheaval for me. As for many people, a life-changing event like that can require a lot to deal with. Learning to think about things like a Stoic has helped me to negotiate all of these things in life.

Donald Robertson

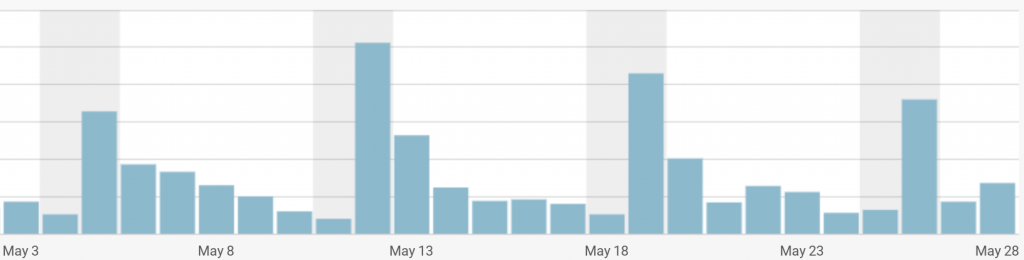

Although I haven't done it since August 2010(!) I used to do something which I referred to as "calling myself into the office". The idea was that I'd set myself three to five goals, and then review them at the end of the month. I'd also set myself some new goals.

The value of doing this is that you can see that you're making progress. It's something that I should definitely start doing again. I was reminded of this approach after reading an article at Career Contessa about weekly self-evaluations. The suggested steps are:

While Career Contessa suggests this will all take only five minutes, I think that if you did it properly it might take more like 20 minutes to half an hour. Whether you do it weekly or monthly probably depends on the size of the goals you're trying to achieve. Either way, it's a valuable exercise.

We all need to cut ourselves some slack, to go easy on ourselves. The chances are that the thing we're worrying about isn't such a big deal in the scheme of things, and the world won't end if we don't get that thing done right now. Perhaps regular self-examination, whether through Stoicism or weekly/monthly reviews, can help more of us with that?

Also check out:

The proper amount of wealth is that which neither descends to poverty nor is far distant from it

So said Seneca, in a quotation I found via the consistently-excellent New Philosopher magazine. In my experience, 'wealth' is a relative concept. I've met people who are, to my mind, fabulously well-off, but don't feel it because their peers are wealthier. Likewise, I've met people who aren't materially well-off, but don't realise they're poor because their friends and colleagues are too.

Let's talk about inequality. Cory Doctorow, writing for BoingBoing, points to an Institute for Fiscal Studies report (PDF) by Robert Joyce and Xiaowei Xu that is surprisingly readable. They note cultural differences around inequality and its link to (perceived) meritocracy:

A recent experiment found that people were much more accepting of inequality when it resulted from merit instead of luck (Almas, Cappelen and Tungodden, 2019). Given the opportunity to redistribute gains to others, people were significantly less likely to do so when differences in gains reflected differences in productivity. The experiment also revealed differences between countries in people’s views of what is fair, with more Norwegians opting for redistribution even when gains were merit-based and more Americans accepting inequality even when outcomes were due to luck.

This suggests that to understand whether inequality is a problem, we need to understand the sources of inequality, views of what is fair and the implications of inequality as well as the levels of inequality. Are present levels of inequalities due to well-deserved rewards or to unfair bargaining power, regulatory failure or political capture? Can meritocracy be unfair? What is the moral status of luck? And what if inequalities derived from a fair process in one generation are transmitted on to future generations?

Robert Joyce and Xiaowei Xu

Can meritocracy be unfair? Yes, of course it can, as I pointed out in this article from a few years back. To quote myself:

I’d like to see meritocracy consigned to the dustbin of history as an outdated approach to society. At a time in history when we seek to be inclusive, to recognise and celebrate diversity, the use of meritocratic practices seems reactionary and regressive. Meritocracy applies a one-size-fits-all, cookie-cutter approach that — no surprises here — just happens to privilege those already in positions of power.

Doug Belshaw

Doctorow also cites Chris Dillow, who outlines in a blog post eight reasons why inequality makes us poorer. Dillow explains that "what matters is not so much the level of inequality as the effect it has". I've attempted to summarise his reasons below:

Meanwhile, Eleanor Ainge Roy reports for The Guardian that the New Zealand government has unveiled a 'wellbeing budget' focused on "mental health services and child poverty as well as record investment in measures to tackle family violence". Their finance minister is quoted by Roy as saying:

For me, wellbeing means people living lives of purpose, balance and meaning to them, and having the capabilities to do so.

This gap between rhetoric and reality, between haves and have-nots, between the elites and the people, has been exploited by populists around the globe.

Grant Robertson

Thankfully, we don't have to wait for government to act on inequality. We can seize the initiative ourselves through co-operation. In The Boston Globe, Andy Rosen explains that different ways of organising are becoming more popular:

The idea has been percolating for a while in some corners of the tech world, largely as a response to the gig economy, in which workers are often considered contractors and don’t get the same protections and benefits as employees. In New York, for example, Up & Go, a kind of Uber for house cleaning, is owned by the cleaners who provide the services.

[...]

People who have followed the co-op movement say the model, and a broader shift toward increased employee and consumer control, is likely to become more prominent in coming years, especially as aging baby boomers look for socially responsible ways to cash out and retire by selling their companies to groups of employees.

ANdy Rosen

Some of the means by which we can make society a fairer and more equal place come through government intervention at the policy level. But we should never forget the power we have through self-organising and co-operating together.

Also check out:

Situations can be described but not given names

So said that most enigmatic of philosophers, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Today's article is about the effect of external stimulants on us as human beings, whether or not we can adequately name them.

Let's start with music, one of my favourite things in all the world. If the word 'passionate' hadn't been devalued from rampant overuse, I'd say that I'm passionate about music. One of the reasons is because it produces such a dramatic physiological response in me; my hairs stand on end and I get a surge of endophins — especially if I'm also running.

That's why Greg Evans' piece for The Independent makes me feel quite special. He reports on (admittedly small-scale) academic research which shows that some people really do feel music differently to others:

Matthew Sachs a former undergraduate at Harvard, last year studied individuals who get chills from music to see how this feeling was triggered.

The research examined 20 students, 10 of which admitted to experiencing the aforementioned feelings in relation to music and 10 that didn't and took brain scans of all of them all.

He discovered that those that had managed to make the emotional and physical attachment to music actually have different brain structures than those that don't.

The research showed that they tended to have a denser volume of fibres that connect their auditory cortex and areas that process emotions, meaning the two can communicate better.

Greg Evans

This totally makes sense to me. I'm extremely emotionally invested in almost everything I do, especially my work. For example, I find it almost unbearably difficult to work on something that I don't agree with or think is important.

The trouble with this, of course, and for people like me, is that unless we're careful we're much more likely to become 'burned out' by our work. Nate Swanner reports for Dice that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has recently recognised burnout as a legitimate medical syndrome:

The actual definition is difficult to pin down, but the WHO defines burnout by these three markers:

Interestingly enough, the actual description of burnout asks that all three of the above criteria be met. You can’t be really happy and not producing at work; that’s not burnout.

As the article suggests, now burnout is a recognised medical term, we now face the prospect of employers being liable for causing an environment that causes burnout in their employees. It will no longer, hopefully, be a badge of honour to have burned yourself out for the sake of a venture capital-backed startup.

Having experienced burnout in my twenties, the road to recovery can take a while, and it has an effect on the people around you. You have to replace negative thoughts and habits with new ones. I ultimately ended up moving both house and sectors to get over it.

As Jason Fried notes on Signal v. Noise, we humans always form habits:

When we talk about habits, we generally talk about learning good habits. Or forming good habits. Both of these outcomes suggest we can end up with the habits we want. And technically we can! But most of the habits we have are habits we ended up with after years of unconscious behavior. They’re not intentional. They’ve been planting deep roots under the surface, sight unseen. Fertilized, watered, and well-fed by recurring behavior. Trying to pull that habit out of the ground later is going to be incredibly difficult. Your grip has to be better than its grip, and it rarely is.

Jason Fried

This is a great analogy. It's easy for weeds to grow in the garden of our mind. If we're not careful, as Fried points out, these can be extremely difficult to get rid of once established. That's why, as I've discussed before, tracking one's habits is itself a good habit to get into.

Over a decade ago, a couple of years after suffering from burnout, I wrote a post outlining what I rather grandly called The Vortex of Uncompetence. Let's just say that, if you recognise yourself in any of what I write in that post, it's time to get out. And quickly.

Also check out:

There’s no perfection where there’s no selection

So said Baltasar Gracián. One of the reasons that e-portfolios never really took off was because there's so much to read. Can you imagine sifting through hundreds of job applications where each applicant had a fully-fledged e-portfolio, including video content?

That's why I've been so interested in Open Badges, and have written plenty on the subject over the last eight years. If you're new to the party, there are various terms such as 'microcredentials', 'digital badges', and 'digital credentials'. The difference is in the standard which was previously stewarded by Mozilla (including at my time there) and now by IMS Global Learning Consortium.

When I left Mozilla, I did a lot of work with City & Guilds, an awarding body that's well known for its vocational qualifications. They took a particular interest in Open Badges, for obvious reasons. In this article for FE News, Kirstie Donnelly (Managing Director of the City & Guilds Group) explains their huge potential:

The fact that you can actually stack these credentials, and they become portable, then you can publish them through online, through your LinkedIn. I just think it puts a very different dynamic into how the learner owns their experience, but at the same time the employers and the education system can still influence very much how those credentials are built and stacked.

Kirstie Donnelly

Like it or not, a lot of education is 'signalling' — i.e. providing an indicator that you can do a thing. The great thing about Open Badges is that you can make credentials much more granular and, crucially, include evidence of your ability to do the thing you claim to be able to do.

As Tyler Cowen picks up on for Marginal Revolution, without this granularity, there's a knock-on effect upon societal inequality. Privilege is perpetuated. He quotes a working paper by Gaurab Aryal, Manudeep Bhuller, and Fabian Lange who state:

The social and the private returns to education differ when education can increase productivity and also be used to signal productivity. We show how instrumental variables can be used to separately identify and estimate the social and private returns to education within the employer learning framework of Farber and Gibbons (1996) and Altonji and Pierret (2001). What an instrumental variable identifies depends crucially on whether the instrument is hidden from or observed by the employers. If the instrument is hidden, it identifies the private returns to education, but if the instrument is observed by employers, it identifies the social returns to education.

Aryal, Bhuller, and Lange

I take this to mean that, in a marketplace, the more the 'buyers' (i.e. employers) understand what's on offer, the more this changes the way that 'sellers' (i.e. potential employees) position themselves. Open Badges and other technologies can help with this.

Understandably, a lot is made of digital credentials for recruitment. Indeed, I've often argued that badges are important at times of transition — whether into a job, on the job, or onto your next job. But they are also important for reasons other than employment.

Lauren Acree, writing for Digital Promise explains how they can be used to foster more inclusive classrooms:

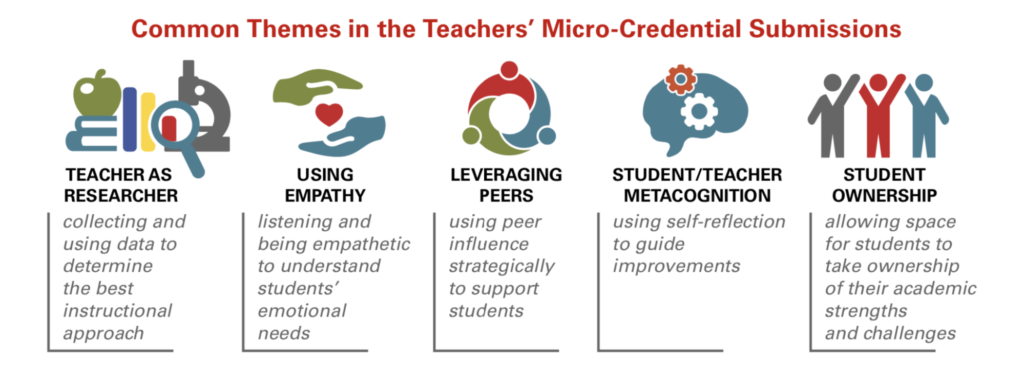

The Learner Variability micro-credentials ask educators to better understand students as learners. The micro-credentials support teachers as they partner with students in creating learning environments that address learners’ needs, leverage their strengths, and empower students to reflect and adjust as needed. We found that micro-credentials are one important way we can ultimately build teacher capacity to meet the needs of all learners.

Lauren Acree

The article includes this image representing a taxonomy of how teachers use micro-credentials in their work:

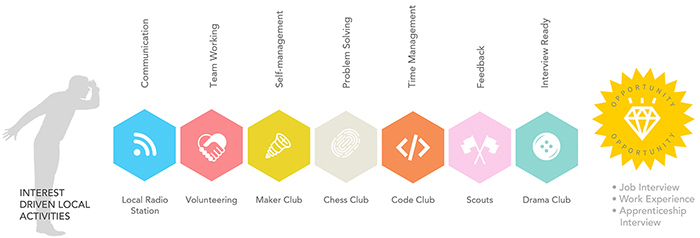

If we zoom out even further, we can see that micro-credentials as a form of 'currency' could play a big role in how we re-imagine society. Tim Riches, who I collaborated with while at both Mozilla and City & Guilds, has written a piece for the RSA about the 'Cities of Learning' projects that he's been involved in. All of these have used badges in some form or other.

In formal education, the value of learning is measured in qualifications. However, qualifications only capture a snapshot of what we know, not what we can do. What’s more, they tend to measure routine skills - the ones most vulnerable to automation and outsourcing.

[...]

Cities are full of people with unrecognised talents and potential. Cities are a huge untapped resource. Skills are developed every day in the community, at work and online, but they are hidden from view - disconnected from formal education and employers.

Tim Riches

I don't live in a city, and don't necessarily see them as the organising force here, but I do think that, on a societal level, there's something about recognising potential. Tim includes a graphic in his article which, I think, captures this nicely:

There's a phrase that's often used by feminist writers: "you can't be what you can't see". In other words, if you don't have any role models in a particular area, you're unlikely to think of exploring it. Similarly, if you don't know anyone who's a lawyer, or a sailor, or a horse rider, it's not perhaps something you'd think of doing.

If we can wrest control of innovations such as Open Badges away from the incumbents, and focus on human flourishing, I can see real opportunities for what Serge Ravet and others call 'open recognition'. Otherwise, we're just co-opting them to prop up and perpetuate the existing, unequal system.

Also check out:

Friday fathomings

I enjoyed reading these:

Image via Indexed

There’s no viagra for enlightenment

This quotation from the enigmatic Russell Brand seemed appropriate for the subject of today's article: the impact of so-called 'deepfakes' on everything from porn to politics.

First, what exactly are 'deepfakes'? Mark Wilson explains in an article for Fast Company:

In early 2018, [an anonymous Reddit user named Deepfakes] uploaded a machine learning model that could swap one person’s face for another face in any video. Within weeks, low-fi celebrity-swapped porn ran rampant across the web. Reddit soon banned Deepfakes, but the technology had already taken root across the web–and sometimes the quality was more convincing. Everyday people showed that they could do a better job adding Princess Leia’s face to The Force Awakens than the Hollywood special effects studio Industrial Light and Magic did. Deepfakes had suddenly made it possible for anyone to master complex machine learning; you just needed the time to collect enough photographs of a person to train the model. You dragged these images into a folder, and the tool handled the convincing forgery from there.

Mark Wilson

As you'd expect, deepfakes bring up huge ethical issues, as Jessica Lindsay reports for Metro. It's a classic case of our laws not being able to keep up with what's technologically possible:

With the advent of deepfake porn, the possibilities have expanded even further, with people who have never starred in adult films looking as though they’re doing sexual acts on camera.

Experts have warned that these videos enable all sorts of bad things to happen, from paedophilia to fabricated revenge porn.

[...]

This can be done to make a fake speech to misrepresent a politician’s views, or to create porn videos featuring people who did not star in them.

Jessica Lindsay

It's not just video, either, with Google's AI now able to translate speech from one language to another and keep the same voice. Karen Hao embeds examples in an article for MIT Technology Review demonstrating where this is all headed.

The results aren’t perfect, but you can sort of hear how Google’s translator was able to retain the voice and tone of the original speaker. It can do this because it converts audio input directly to audio output without any intermediary steps. In contrast, traditional translational systems convert audio into text, translate the text, and then resynthesize the audio, losing the characteristics of the original voice along the way.

Karen Hao

The impact on democracy could be quite shocking, with the ability to create video and audio that feels real but is actually completely fake.

However, as Mike Caulfield notes, the technology doesn't even have to be that sophisticated to create something that can be used in a political attack.

There’s a video going around that purportedly shows Nancy Pelosi drunk or unwell, answering a question about Trump in a slow and slurred way. It turns out that it is slowed down, and that the original video shows her quite engaged and articulate.

[...]

In musical production there is a technique called double-tracking, and it’s not a perfect metaphor for what’s going on here but it’s instructive. In double tracking you record one part — a vocal or solo — and then you record that part again, with slight variations in timing and tone. Because the two tracks are close, they are perceived as a single track. Because they are different though, the track is “widened” feeling deeper, richer. The trick is for them to be different enough that it widens the track but similar enough that they blend.

Mike Caulfield

This is where blockchain could actually be a useful technology. Caulfield often talks about the importance of 'going back to the source' — in other words, checking the provenance of what it is you're reading, watching, or listening. There's potential here for checking that something is actually the original document/video/audio.

Ultimately, however, people believe what they want to believe. If they want to believe Donald Trump is an idiot, they'll read and share things showing him in a negative light. It doesn't really matter if it's true or not.

Also check out:

Wretched is a mind anxious about the future

So said one of my favourite non-fiction authors, the 16th century proto-blogger Michel de Montaigne. There's plenty of writing about how we need to be anxious because of the drift towards a future of surveillance states. Eventually, because it's not currently affecting us here and now, we become blasé. We forget that it's already the lived experience for hundreds of millions of people.

Take China, for example. In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson writes about the Chinese government's brutality against the Muslim Uyghur population in the western province of Xinjiang:

[The] horrifying situation is built on the scaffolding of mass surveillance. Cameras fill the marketplaces and intersections of the key city of Kashgar. Recording devices are placed in homes and even in bathrooms. Checkpoints that limit the movement of Muslims are often outfitted with facial-recognition devices to vacuum up the population’s biometric data. As China seeks to export its suite of surveillance tech around the world, Xinjiang is a kind of R&D incubator, with the local Muslim population serving as guinea pigs in a laboratory for the deprivation of human rights.

Derek Thompson

As Ian Welsh points out, surveillance states usually involve us in the West pointing towards places like China and shaking our heads. However, if you step back a moment and remember that societies like the US and UK are becoming more unequal over time, then perhaps we're the ones who should be worried:

The endgame, as I’ve been pointing out for years, is a society in which where you are and what you’re doing, and have done is, always known, or at least knowable. And that information is known forever, so the moment someone with power wants to take you out, they can go back thru your life in minute detail. If laws or norms change so that what was OK 10 or 30 years ago isn’t OK now, well they can get you on that.

Ian Welsh

As the world becomes more unequal, the position of elites becomes more perilous, hence Silicon Valley billionaires preparing boltholes in New Zealand. Ironically, they're looking for places where they can't be found, while making serious money from providing surveillance technology. Instead of solving the inequality, they attempt to insulate themselves from the effect of that inequality.

A lot of the crazy amounts of money earned in Silicon Valley comes at the price of infringing our privacy. I've spent a long time thinking about quite nebulous concept. It's not the easiest thing to understand when you examine it more closely.

Privacy is usually considered a freedom from rather than a freedom to, as in "freedom from surveillance". The trouble is that there are many kinds of surveillance, and some of these we actively encourage. A quick example: I know of at least one family that share their location with one another all of the time. At the same time, of course, they're sharing it with the company that provides that service.

There's a lot of power in the 'default' privacy settings devices and applications come with. People tend to go with whatever comes as standard. Sidney Fussell writes in The Atlantic that:

Many apps and products are initially set up to be public: Instagram accounts are open to everyone until you lock them... Even when companies announce convenient shortcuts for enhancing security, their products can never become truly private. Strangers may not be able to see your selfies, but you have no way to untether yourself from the larger ad-targeting ecosystem.

Sidney Fussell

Some of us (including me) are willing to trade some of that privacy for more personalised services that somehow make our lives easier. The tricky thing is when it comes to employers and state surveillance. In these cases there are coercive power relationships at play, rather than just convenience.

Ellen Sheng, writing for CNBC explains how employees in the US are at huge risk from workplace surveillance:

In the workplace, almost any consumer privacy law can be waived. Even if companies give employees a choice about whether or not they want to participate, it’s not hard to force employees to agree. That is, unless lawmakers introduce laws that explicitly state a company can’t make workers agree to a technology...

One example: Companies are increasingly interested in employee social media posts out of concern that employee posts could reflect poorly on the company. A teacher’s aide in Michigan was suspended in 2012 after refusing to share her Facebook page with the school’s superintendent following complaints about a photo she had posted. Since then, dozens of similar cases prompted lawmakers to take action. More than 16 states have passed social media protections for individuals.

Ellen Sheng

It's not just workplaces, though. Schools are hotbeds for new surveillance technologies, as Benjamin Herold notes in an article for Education Week:

Social media monitoring companies track the posts of everyone in the areas surrounding schools, including adults. Other companies scan the private digital content of millions of students using district-issued computers and accounts. Those services are complemented with tip-reporting apps, facial-recognition software, and other new technology systems.

[...]

While schools are typically quiet about their monitoring of public social media posts, they generally disclose to students and parents when digital content created on district-issued devices and accounts will be monitored. Such surveillance is typically done in accordance with schools’ responsible-use policies, which students and parents must agree to in order to use districts’ devices, networks, and accounts.

Benjamin Herold

Hypothetically, students and families can opt out of using that technology. But doing so would make participating in the educational life of most schools exceedingly difficult.

In China, of course, a social credit system makes all of this a million times worse, but we in the West aren't heading in a great direction either.

We're entering a time where, by the time my children are my age, companies, employers, and the state could have decades of data from when they entered the school system through to them finding jobs, and becoming parents themselves.

There are upsides to all of this data, obviously. But I think that in the midst of privacy-focused conversations about Amazon's smart speakers and Google location-sharing, we might be missing the bigger picture around surveillance by educational institutions, employers, and governments.

Returning to Ian Welsh to finish up, remember that it's the coercive power relationships that make surveillance a bad thing:

Surveillance societies are sterile societies. Everyone does what they’re supposed to do all the time, and because we become what we do, it affects our personalities. It particularly affects our creativity, and is a large part of why Communist surveillance societies were less creative than the West, particularly as their police states ramped up.

Ian Welsh

We don't want to think about all of this, though, do we?

Also check out:

Only thoughts conceived while walking have any value

Philosopher and intrepid walker Friedrich Nietzsche is well known for today's quotation-as-title. Fellow philosopher Immanuel Kant was a keen walker, too, along with Henry David Thoreau. There's just something about big walks and big thoughts.

I spent a good part of yesterday walking about 30km because I woke wanting to see the sea. It has a calming effect on me, and my wife was at work with the car. Forty-thousand steps later, I'd not only succeeded in my mission and taken the photo that accompanies this post, but managed to think about all kinds of things that definitely wouldn't have entered my mind had I stayed at home.

I want to focus the majority of this article on a single piece of writing by Craig Mod, whose walk across Japan I followed by SMS. Instead of sharing the details of his 620 mile, six-week trek via social media, he instead updated a server which then sent text messages (with photographs, so technically MMS) to everyone who'd signed up to receive them. Readers could reply, but he didn't receive these until he'd finished the walk and they'd been automatically curated into a book and sent to him.

Writing in WIRED, Mod talks of his "glorious, almost-disconnected walk" which was part experiment, part protest:

I have configured servers, written code, built web pages, helped design products used by millions of people. I am firmly in the camp that believes technology is generally bending the world in a positive direction. Yet, for me, Twitter foments neurosis, Facebook sadness, Google News a sense of foreboding. Instagram turns me covetous. All of them make me want to do it—whatever “it” may be—for the likes, the comments. I can’t help but feel that I am the worst version of myself, being performative on a very short, very depressing timeline. A timeline of seconds.

[...]

So, a month ago, when I started walking, I decided to conduct an experiment. Maybe even a protest. I wanted to test hypotheses. Our smartphones are incredible machines, and to throw them away entirely feels foolhardy. The idea was not to totally disconnect, but to test rational, metered uses of technology. I wanted to experience the walk as the walk, in all of its inevitably boring walkiness. To bask in serendipitous surrealism, not just as steps between reloading my streams. I wanted to experience time.

Craig Mod

I love this, it's so inspiring. The most number of consecutive days I've walked is only two, so I can't even really imagine what it must be like to walk for weeks at a time. It's a form of meditation, I suppose, and a way to re-centre oneself.

The longness of an activity is important. Hours or even days don’t really cut it when it comes to long. “Long” begins with weeks. Weeks of day-after-day long walking days, 30- or 40-kilometer days. Days that leave you wilted and aware of all the neglect your joints and muscles have endured during the last decade of sedentary YouTubing.

[...]

In the context of a walk like this, “boredom” is a goal, the antipode of mindless connectivity, constant stimulation, anger and dissatisfaction. I put “boredom” in quotes because the boredom I’m talking about fosters a heightened sense of presence. To be “bored” is to be free of distraction.

Craig Mod

I find that when I walk for any period of time, certain songs start going through my head. Yesterday, for example, my brain put on repeat the song Good Enough by Dodgy from their album Free Peace Sweet. The time before it was We Can Do It from Jamiroquai's latest album Automaton. I'm not sure where it comes from, although the beat does have something to do with my pace.

Walking by oneself seems to do something to the human brain akin to unlocking the subconscious. That's why I'm not alone in calling it a 'meditative' activity. While I enjoy walking with others, the brain seems to start working a different way when you're by yourself being propelled by your own two legs.

It's easy to feel like we're not 'keeping up' with work, with family and friends, and with the news. The truth is, however, that the most important person to 'keep up' with is yourself. Having a strong sense of self, I believe, is the best way to live a life with meaning.

It might sound 'boring' to go for a long walk, but as Alain de Botton notes in The News: a user's manual, getting out of our routine is sometimes exactly what we need:

What we colloquially call 'feeling bored' is just the mind, acting out of a self-preserving reflex, ejecting information it has despaired of knowing where to place.

Alain de Botton

I'm not going to tell you what I thought about during my walk today as, outside of the rich (inner and outer) context in which the thinking took place, whatever I write would probably sound banal.

To me, however, the thoughts I had today will, like all of the thoughts I've had while doing some serious walking, help me organise my future actions. Perhaps that's what Nietzsche meant when he said that only thoughts conceived while walking have any value.

Also check out:

What is no good for the hive is no good for the bee

So said Roman Emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius. In this article, I want to apply that to our use of technology as well as the stories we tell one another about that technology use.

Let's start with an excellent post by Nolan Lawson, who when I started using Twitter less actually deleted his account and went all-in on the Fediverse. He maintains a Mastodon web client called Pinafore, and is a clear-headed thinker on all things open. The post is called Tech veganism and sums up the problem I have with holier-than-thou open advocates:

I find that there’s a bit of a “let them eat cake” attitude among tech vegan boosters, because they often discount the sheer difficulty of all this stuff. (“Let them use Linux” could be a fitting refrain.) After all, they figured it out, so why can’t you? What, doesn’t everyone have a computer science degree and six years experience as a sysadmin?

To be a vegan, all you have to do is stop eating animal products. To be a tech vegan, you have to join an elite guild of tech wizards and master their secret arts. And even then, you’re probably sneaking a forbidden bite of Google or Apple every now and then.

Nolan Lawson

It's that second paragraph that's the killer for me. I'm pescetarian and probably about the equivalent of that, in Lawson's lingo, when it comes to my tech choices. I definitely agree with him that the conversation is already changing away from open source and free software to what Mark Zuckerberg (shudder) calls "time well spent":

I also suspect that tech veganism will begin to shift, if it hasn’t already. I think the focus will become less about open source vs closed source (the battle of the last decade) and more about digital well-being, especially in regards to privacy, addiction, and safety. So in this way, it may be less about switching from Windows to Linux and more about switching from Android to iOS, or from Facebook to more private channels like Discord and WhatsApp.

Nolan Lawson

This is reminiscent of Yancey Strickler's notion of 'dark forests'. I can definitely see more call for nuance around private and public spaces.

So much of this, though, depends on your worldview. Everyone likes the idea of 'freedom', but are we talking about 'freedom from' or 'freedom to'? How important are different types of freedom? Should all information be available to everyone? Where do rights start and responsibilities stop (and vice-versa)?

One thing I've found fascinating is how the world changes and debates get left behind. For example, the idea (and importance) of Linux on the desktop has been something that people have been discussing most of my adult life. At the same time, cloud computing has changed the game, with a lot of the data processing and heavy lifting being done by servers — most of which are powered by Linux!

Mark Shuttleworth, CEO of Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu Linux, said in a recent interview:

I think the bigger challenge has been that we haven't invented anything in the Linux that was like deeply, powerfully ahead of its time... if in the free software community we only allow ourselves to talk about things that look like something that already exists, then we're sort of defining ourselves as a series of forks and fragmentations.

Mark Shuttleworth

This is a problem that's wider than just software. Those of us who are left-leaning are more likely to let small ideological differences dilute our combined power. That affects everything from opposing Brexit, to getting people to switch to Linux. There's just too much noise, too many competing options.

Meanwhile, as the P2P Foundation notes, businesses swoop in and use open licenses to enclose the Commons:

[I]t is clear that these Commons have become an essential infrastructure without which the Internet could no longer function today (90% of the world’s servers run on Linux, 25% of websites use WordPress, etc.) But many of these projects suffer from maintenance and financing problems, because their development depends on communities whose means are unrelated to the size of the resources they make available to the whole world.

[...]

This situation corresponds to a form of tragedy of the Commons, but of a different nature from that which can strike material resources. Indeed, intangible resources, such as software or data, cannot by definition be over-exploited and they even increase in value as they are used more and more. But tragedy can strike the communities that participate in the development and maintenance of these digital commons. When the core of individual contributors shrinks and their strengths are exhausted, information resources lose quality and can eventually wither away.

P2P Foundation

So what should we do? One thing we've done with MoodleNet is to ensure that it has an AGPL license, one that Google really doesn't like. They state perfectly the reasons why we selected it:

The primary risk presented by AGPL is that any product or service that depends on AGPL-licensed code, or includes anything copied or derived from AGPL-licensed code, may be subject to the virality of the AGPL license. This viral effect requires that the complete corresponding source code of the product or service be released to the world under the AGPL license. This is triggered if the product or service can be accessed over a remote network interface, so it does not even require that the product or service is actually distributed.

Google

So, in other words, if you run a server with AGPL code, or create a project with source code derived from it, you must make that code available to others. To me, it has the same 'viral effect' as the Creative Commons BY-SA license.

As Benjamin "Mako" Hill points out in a recent keynote, we need to be a bit more wise when it comes to 'choosing a side'. Cory Doctorow, summarising Mako's keynote says:

[M]arkets discovered free software and turned it into "open source," figuring out how to create developer communities around software ("digital sharecropping") that lowered their costs and increased their quality. Then the companies used patents and DRM and restrictive terms of service to prevent users from having any freedom.

Mako says that this is usually termed "strategic openness," in which companies take a process that would, by default, be closed, and open the parts of it that make strategic sense for the firm. But really, this is "strategic closedness" -- projects that are born open are strategically enclosed by companies to allow them to harvest the bulk of the value created by these once-free systems.

[...]

Mako suggests that the time in which free software and open source could be uneasy bedfellows is over. Companies' perfection of digital sharecropping means that when they contribute to "free" projects, all the freedom will go to them, not the public.

Cory Doctorow

It's certainly an interesting time we live in, when the people who are pointing out all of the problems (the 'tech vegans') are seen as the problem, and the VC-backed companies as the disruptive champions of the people. Tech follows politics, though, I guess.

Also check out:

Friday fabrications

These things made me sit up and take notice:

Image via xkcd

Men fear wanderers for they have no rules

A few years ago, when I was at Mozilla, a colleague mentioned a series of books by Bernard Cornwell called The Last Kingdom. It seemed an obvious fit for me, he said, given that my interest in history and that I live in Northumberland. A couple of years later, I got around to reading the series, and loved it. The quote that serves as the title for this article is from the second book in the series: The Pale Horseman.

Another book I read that I wasn't expecting to enjoy was Ender's Game, a sci-fi novel by Orson Scott Card. I was looking for a quotation about Ender's access to networks when I came across this one from another one of the author's novels:

“Every person is defined by the communities she belongs to.”

Orson Scott Card

Some people say that you're the average of the five people with which you surround yourself. In this day and age, 'surrounding yourself' isn't necessarily a physical activity, it's to do with your interactions, however they occur.

It's easy to think about the time we spend at home with our nearest and dearest, but what about our networked interactions? For example, I've been playing a lot of Red Dead Redemption 2 with Dai Barnes recently, so that might count as an example — and so might the time we spend on Twitter, Instagram, and other social networks.