- Apple created the privacy dystopia it wants to save you from (Fast Company) — I'm not sure I agree with either the title or subtitle of this piece, but it raises some important points.

- When Grown-Ups Get Caught in Teens’ AirDrop Crossfire (The Atlantic) — hilarious and informative in equal measure!

- Anxiety, revolution, kidnapping: therapy secrets from across the world (The Guardian) — a fascinating look at the reasons why people in different countries get therapy.

- Post-it note war over flowers deemed ‘most middle-class argument ever’ (Metro) — amusing, but there's important things to learn from this about private/public spaces.

- Modern shamans: Financial managers, political pundits and others who help tame life’s uncertainty (The Conversation) — a 'cognitive anthropologist' explains the role of shamans in ancient societies, and extends the notion to the modern world.

Therapy is simple

Craig Mod is a couple of months older than me, as I turn 43 just before Christmas. Like me, he’s gone through some therapy. Unlike me, he lives alone, and has continued therapy sessions for over five years.

What I like about the raw honesty of what he writes in this dispatch is how he wishes that everyone had access to therapy. Despite all of the positive messages about mental health, there’s still something of a stigma about getting some help. As if you should just “get over it”.

But therapy is part of how you become you. As Craig says, in the bit that comes after the part I’ve quoted below: “Therapy is simple. You load up FaceTime and speak out loud the things you’re most terrified about in life. Be radically open and honest, treating yourself as a third party, kindly observant without judgement."

It’s hard talking about your hopes, fears, and dreams with people you are emotionally invested in. There’s something remarkably grown-up and liberating about finally being able to start living a more flourishing life by sorting your shit out.

I’ve been thinking about aloneness recently. Well, I’ve been thinking about it my whole life. It’s difficult to remember a time where I didn’t feel alone or apart or “on my own.” And I’ve spent the majority of my adult life — from 17 onward — living mostly alone, going to bed alone, and waking up alone. Left to my own volition to somehow transmute that aloneness into forward momentum, “output,” (“content” ha ha) and positive habits.Source: Tokyo Walk, TBOT Cover, Aloneness | Roden Issue 086[…]

I just turned 43 the other day. As part of the fun of embracing mid-life crises, I’m in pattern matching mode. Two decades of watching friends either pair up and start families (or just embark on paired adventures), or continue down paths of aloneness. It seems to get more and more acute — the effects of aloneness — as folks drift into their 40s. It also seems to be more and more difficult to break habits connected with aloneness the older we get. This makes sense. Habits self-reinforce. And the folks with families have less time for solo people, creating even more dissonance.

[…]

I’ve spent the last five and half years speaking weekly with a therapist in New York over FaceTime. I started because I was exhausted. I recognized toxic relationship patterns that I had held onto since my teenage years, and wanted to break free. And I recognized that I had spent roughly twenty years not being able to do that on my own. (I had made some strides, of course, in fits and starts; most notably when I was 27, then: at the lowest of lows, I began running in the middle of the night (2am, feeling like I was losing my mind, put on my shoes, and ran the silent moonlit summer streets of Tokyo until my lungs burned and I felt back on the ground), soon completing two full marathons, felt my sense of value and self-worth rise, charged more for my time, made my way to Palo Alto, worked with incredible talent, made real money, big projects, huge scale, proved to myself I wasn’t stuck — it was an incredible stretch, thinking back on it now, a stretch of life-transformational love and hugs and sense of support, all initially catalyzed by feeling more alone than ever before, a yawning endless aloneness, and wanting to crawl out of that well before someone came and sealed the top.) Back to five years ago — I was 37 and stuck and thought — OK, let’s try something new. Hence: calling in for support (finally!).

I feel guilty for having access to this therapist. I want everyone to have access to someone like this. The world would be whole if you gave everyone a talented therapist and a cat. I can’t overstate how transformational my weekly act of analysis has been. I am still broken in many obvious (and non-unique) ways. But through these weekly sessions I’ve mitigated a huge chunk of lingering aloneness.

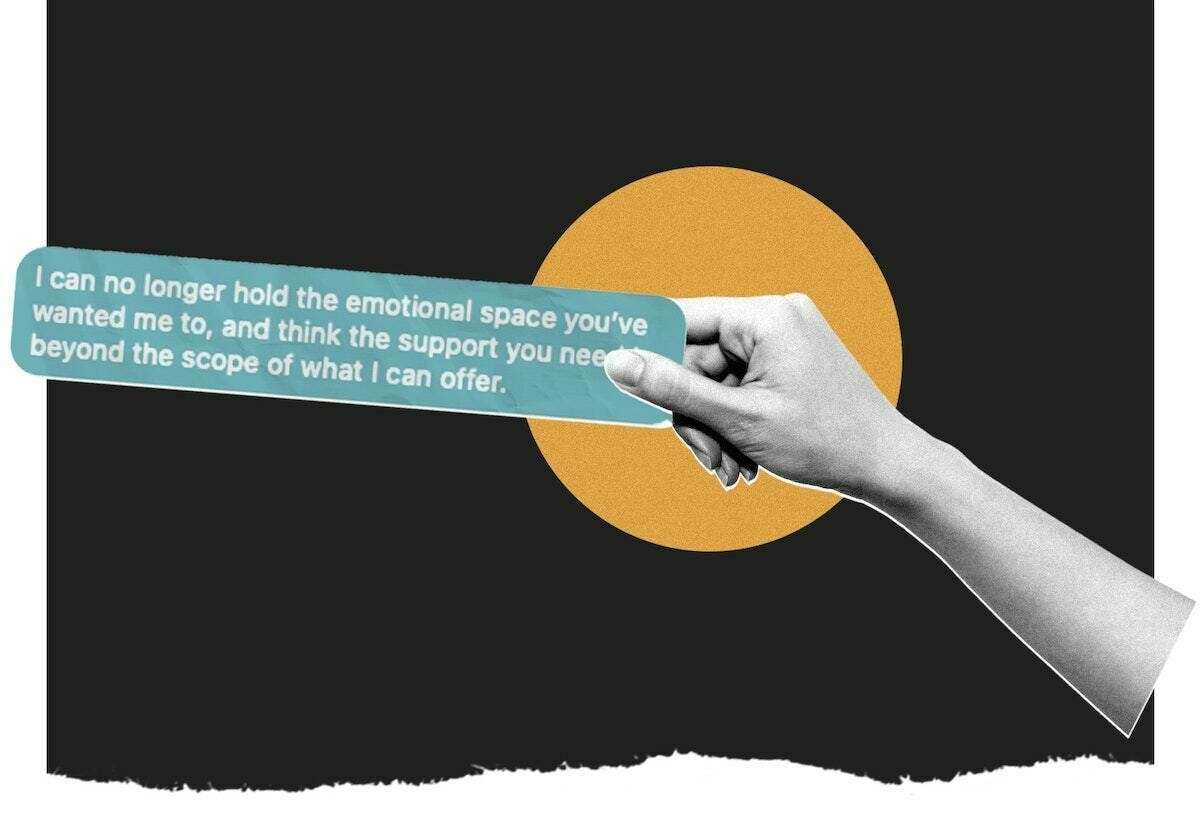

Relationships and therapy-speak

I’m hugely supportive of people choosing therapies such as CBT and using language from NVC. However, it’s possible to go too far.

My wife has told me “not to use that language” with her before when she thinks that I’m using it in a way that doesn’t feel in some way natural. And it seems that it’s particularly prevalent in younger generations? Interesting article.

In recent years, therapy concepts like self-care and boundary-setting have shown up everywhere online, with Instagram accounts and other social media communities sharing mantras and advice advocating for self-actualization. TikTok therapists like Nadia Addesi and TherapyJeff offer tips for struggling with anxiety, self-esteem, and people-pleasing. “Therapy speak” — prescriptive language describing certain psychological concepts and behaviors — can be found everywhere from group chats to dating apps. Now, we have more language to advocate for ourselves and our needs, whether it be canceling plans when we feel overwhelmed or ending relationships that no longer serve us.Source: Is Therapy-Speak Making Us Selfish?It’s important to be able to set boundaries and advocate for yourself. Occasionally, though, the emphasis on protecting one’s individual needs can overlook the fact that someone else is on other side of that boundary-setting. In 2019, for instance, a relationship coach’s Twitter thread offering a template for telling friends in need of support that you’re “at capacity” at the moment drew criticism for equating friendship to emotional labor. Earlier this year, a clinical psychologist’s TikTok video outlining how to break up with a friend went viral after viewers pointed out that it sounded like a missive from HR. Critics have noted that personal relationships require a touch more compassion than some of these therapeutic blueprints offer.

[…]

There are reasons a person might be tempted to overindulge in some of this self-care behavior. Conflict can be difficult, and people might think they can avoid it by asserting their needs in a way that prevents the other person from responding — by using HR language to end a friendship, for instance, or via straight-up ghosting. And by couching the behavior in therapy language, the hard “boundary” can feel more legitimate, or even virtuous.

[…]

Beyond boundary-setting and inflexibility, the proliferation of therapy speak has also inspired some people to assign labels like “toxic” and “narcissistic” to certain relationships or behaviors. Though toxic people and narcissists do exist, these armchair diagnoses don’t always accurately capture every dynamic, and being on the receiving end of this language can be destabilizing when it’s misplaced.

Pain, suffering, and scuba diving

In this post, Derek Sivers shares his experience of a panic attack during a scuba diving trip and being calmed down by his instructor. He then subsequently used the same technique to help someone else who wasn’t OK on a later trip.

Pain and suffering are part of the human experience. For anyone ask “why me?” doesn’t make sense. There are those who dissimulate and those who don’t, but underneath it all there is hardship.

There is less stigma around therapy than there used to be, but I haven’t met anyone (me included!) who hasn’t transformed their life for the better after going through some form of counselling.

I learned a few lessons from this experience.Source: scuba, panic, empathy | Derek SiversThere are things in life we think won’t apply to us: Panic. Addiction. Depression.

I thought that was for other people. I thought I wasn’t that type. Why is this happening to me?

But I learned so much empathy that day. These things that only seem to happen to other people can happen to me. We’re not so different. It helps me recognize it in others, and be most helpful by remembering that feeling.

I imagine this is why people, who have been through really hard times, become counselors.

That day also reinforced the power of imitation. My teacher calmed me down so well that it was best to just imitate him.

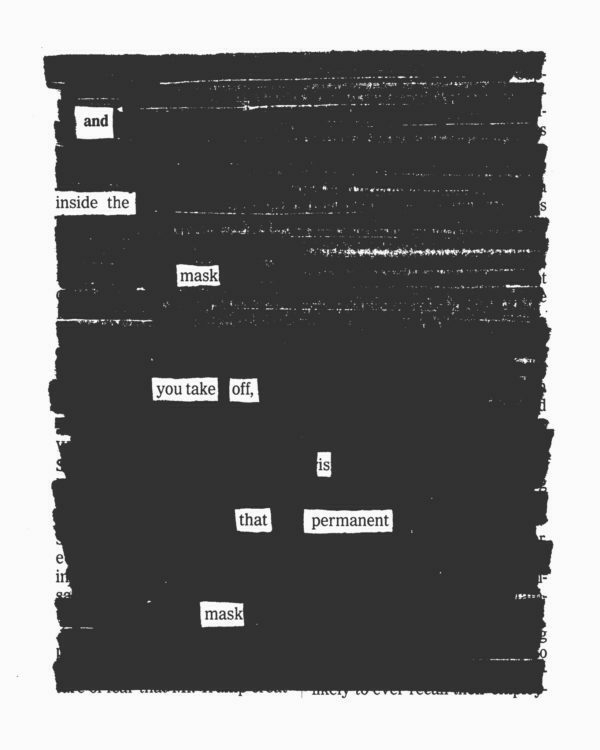

The permanent mask

I’m sharing this mainly for the blackout poetry, but I also appreciate the quotation from Nabakov that Austin Kleon shares in this post.

As I explained in my checking out of therapy post, you can “paint yourself into a rather unhelpful corner by being the person everyone else expects you to be”. Taking off that mask can be liberating.

I don’t think that an artist should bother about his audience. His best audience is the person he sees in his shaving mirror every morning. I think that the audience an artist imagines, when he imagines that kind of a thing, is a room filled with people wearing his own mask.Source: Inside the mask | Austin Kleon

Main-Character Energy

Before starting therapy, my wife said that she was concerned that I might “lose my superpowers”. One of the ways of thinking about this is as the Main-Character Energy discussed in this New Yorker article. It’s a vitality you bring to each day because you see yourself in a starring role.

Therapy did strip me of that, but in a good way. Instead of some Hollywood actor, I now see myself in a much more realistic light, rather in the way that social media can distort and mediate the view I have of myself. It means that I see myself a part of a whole, rather than set apart from it.

The impulse to see oneself as the focal point of the action is all the more powerful as we emerge from the dull isolation of the pandemic, when activities were limited to the likes of re-growing scallions and feeding bulbous sourdough starters. Post-covid, we want to reclaim control of our stories, exert ourselves upon the world, take our places as protagonists once more—and then post about it. During quarantine, the Internet was one of the few tethers to public connection. But publishing evidence of any social engagements, even C.D.C.-compliant ones, came with the risk of being shamed as reckless or self-indulgent. Now, suddenly, much of that fear of critique is gone. The “return of fomo,” as a recent New York cover described it, means the return of jealousy-inducing Instagram stories and glamorous TikToks.Source: We All Have “Main-Character Energy” Now | The New Yorker

Friday fathomings

I enjoyed reading these:

Image via Indexed