- Some of your talents and skills can cause burnout. Here’s how to identify them (Fast Company) — "You didn’t mess up somewhere along the way or miss an important lesson that the rest of us received. We’re all dealing with gifts that drain our energy, but up until now, it hasn’t been a topic of conversation. We aren’t discussing how we end up overusing our gifts and feeling depleted over time."

- Learning from surveillance capitalism (Code Acts in Education) — "Terms such as ‘behavioural surplus’, ‘prediction products’, ‘behavioural futures markets’, and ‘instrumentarian power’ provide a useful critical language for decoding what surveillance capitalism is, what it does, and at what cost."

- Facebook, Libra, and the Long Game (Stratechery) — "Certainly Facebook’s audacity and ambition should not be underestimated, and the company’s network is the biggest reason to believe Libra will work; Facebook’s brand is the biggest reason to believe it will not."

- The Pixar Theory (Jon Negroni) — "Every Pixar movie is connected. I explain how, and possibly why."

- Mario Royale (Kottke.org) — "Mario Royale (now renamed DMCA Royale to skirt around Nintendo’s intellectual property rights) is a battle royale game based on Super Mario Bros in which you compete against 74 other players to finish four levels in the top three. "

- Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think (The Atlantic) — "In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s."

- What Happens When Your Kids Develop Their Own Gaming Taste (Kotaku) — "It’s rewarding too, though, to see your kids forging their own path. I feel the same way when I watch my stepson dominate a round of Fortnite as I probably would if he were amazing at rugby: slightly baffled, but nonetheless proud."

- Whence the value of open? (Half an Hour) — "We will find, over time and as a society, that just as there is a sweet spot for connectivity, there is a sweet spot for openness. And that point where be where the default for openness meets the push-back from people on the basis of other values such as autonomy, diversity and interactivity. And where, exactly, this sweet spot is, needs to be defined by the community, and achieved as a consensus."

- How to Be Resilient in the Face of Harsh Criticism (HBR) — "Here are four steps you can try the next time harsh feedback catches you off-guard. I’ve organized them into an easy-to-remember acronym — CURE — to help you put these lessons in practice even when you’re under stress."

- Fans Are Better Than Tech at Organizing Information Online (WIRED) — "Tagging systems are a way of imposing order on the real world, and the world doesn't just stop moving and changing once you've got your nice categories set up."

- The fake French minister in a silicone mask who stole millions (BBC News) — "For two years from late 2015, an individual or individuals impersonating France's defence minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, scammed an estimated €80m (£70m; $90m) from wealthy victims including the Aga Khan and the owner of Château Margaux wines."

- No, You Don’t Really Look Like That (The Atlantic) — "The global economy is wired up to your face. And it is willing to move heaven and Earth to let you see what you want to see."

- Can You Unwrinkle A Raisin? (FiveThirtyEight) — "Back when you couldn’t just go buy a bottle of wine, folks would, instead, buy a giant brick of raisins, soak them in water to rehydrate the dried-out fruit and then store that juice in a dark cupboard for 60 days."

- What Ecstasy Does to Octopuses (The Atlantic) — "At first they used too high a dose, and the animals “freaked out and did all these color changes”... But once the team found a more suitable dose, the animals behaved more calmly—and more sociably."

- The English Word That Hasn’t Changed in Sound or Meaning in 8,000 Years (Nautilus) — "The word lox was one of the clues that eventually led linguists to discover who the Proto-Indo-Europeans were, and where they lived. "

- Apple created the privacy dystopia it wants to save you from (Fast Company) — I'm not sure I agree with either the title or subtitle of this piece, but it raises some important points.

- When Grown-Ups Get Caught in Teens’ AirDrop Crossfire (The Atlantic) — hilarious and informative in equal measure!

- Anxiety, revolution, kidnapping: therapy secrets from across the world (The Guardian) — a fascinating look at the reasons why people in different countries get therapy.

- Post-it note war over flowers deemed ‘most middle-class argument ever’ (Metro) — amusing, but there's important things to learn from this about private/public spaces.

- Modern shamans: Financial managers, political pundits and others who help tame life’s uncertainty (The Conversation) — a 'cognitive anthropologist' explains the role of shamans in ancient societies, and extends the notion to the modern world.

- A New York School District Will Test Facial Recognition System On Students Even Though The State Asked It To Wait (BuzzFeed News) — "Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has expressed concern in a congressional hearing on the technology last week that facial recognition could be used as a form of social control."

- Amazon preparing a wearable that ‘reads human emotions,’ says report (The Verge) — "This is definitely one of those things that hasn’t yet been done because of how hard it is to do."

- Google’s Sundar Pichai: Privacy Should Not Be a Luxury Good (The New York Times) — "Ideally, privacy legislation would require all businesses to accept responsibility for the impact of their data processing in a way that creates consistent and universal protections for individuals and society as a whole.

- One step ahead: how walking opens new horizons (The Guardian) — "Walking provides just enough diversion to occupy the conscious mind, but sets our subconscious free to roam. Trivial thoughts mingle with important ones, memories sharpen, ideas and insights drift to the surface."

- A Philosophy of Walking (Frédéric Gros) — "a bestseller in France, leading thinker Frédéric Gros charts the many different ways we get from A to B—the pilgrimage, the promenade, the protest march, the nature ramble—and reveals what they say about us."

- What 10,000 Steps Will Really Get You (The Atlantic) — "While basic guidelines can be helpful when they’re accurate, human health is far too complicated to be reduced to a long chain of numerical imperatives. For some people, these rules can even do more harm than good."

- Cleaner and more energy efficient

- More space efficient

- Safer

- Making the

worldcity a better place - Force for economic inclusion

- Micro-mobility revolution has just begun (Stuff) — "Lime Scooters, Onzo Bikes and the like may seem like novelties at the moment but will likely revolutionise urban transport within 20 years."

- Scooters and Second Order Consequences (Scooter Map Blog) — "Micro-mobility will augment the public transit backbone."

- The Right Way to Regulate Electric Scooters (CityLab) — "After all, if a bicycle needs to meet minimum standards for forks and frames, then an e-scooter ought to meet minimum similar requirements for floorboards and stems."

- Global attention span is narrowing and trends don't last as long, study reveals (The Guardian) — "The empirical data found periods where topics would sharply capture widespread attention and promptly lose it just as quickly."

- Existence precedes likes: how online behaviour defines us (Aeon) — "Something strange is happening as our lives migrate from the analogue to the digital."

- Emotional Intelligence: The Social Skills You Weren't Taught in School (Lifehacker) — "People who exhibit emotional intelligence have the less obvious skills necessary to get ahead in life, such as managing conflict resolution, reading and responding to the needs of others, and keeping their own emotions from overflowing and disrupting their lives."

- The circular economy could create an enormous jobs boom (Fast Company) — "The circular economy presents an opportunity to weave together initiatives on innovation, productivity, and job creation with environmental and climate objectives."

- The Vision for a more Decentralized Web (Decentralize.today) — "Today, we see that we have gone too far in the direction of centralization. We have our data abused and sold by the corporations who mostly care about growth."

- Local-first software: you own your data, in spite of the cloud (Ink & Switch) — "Local-first ideals include the ability to work offline and collaborate across multiple devices, while also improving the security, privacy, long-term preservation, and user control of data."

- You can cope on less than five hours' sleep

- Alcohol before bed boosts your sleep

- Watching TV in bed helps you relax

- If you're struggling to sleep, stay in bed

- Hitting the snooze button

- Snoring is always harmless

- The ‘Dark Ages’ Weren’t As Dark As We Thought (Literary Hub) — "At the back of our minds when thinking about the centuries when the Roman Empire mutated into medieval Europe we are unconsciously taking on the spurious guise of specific communities."

- An Easy Mode Has Never Ruined A Game (Kotaku) — "There are myriad ways video games can turn the dials on various systems to change our assessment of how “hard” they seem, and many developers have done as much without compromising the quality or integrity of their games."

- Millennials destroyed the rules of written English – and created something better (Mashable) — "For millennials who conduct so many of their conversations online, this creativity with written English allows us to express things that we would have previously only been conveyed through volume, cadence, tone, or body language."

Friday feeds

These things caught my eye this week:

Header image via Dilbert

Friday fancies

These are some things I came across this week that made me smile:

Image via webcomic.name

Friday fathomings

I enjoyed reading these:

Image via Indexed

Wretched is a mind anxious about the future

So said one of my favourite non-fiction authors, the 16th century proto-blogger Michel de Montaigne. There's plenty of writing about how we need to be anxious because of the drift towards a future of surveillance states. Eventually, because it's not currently affecting us here and now, we become blasé. We forget that it's already the lived experience for hundreds of millions of people.

Take China, for example. In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson writes about the Chinese government's brutality against the Muslim Uyghur population in the western province of Xinjiang:

[The] horrifying situation is built on the scaffolding of mass surveillance. Cameras fill the marketplaces and intersections of the key city of Kashgar. Recording devices are placed in homes and even in bathrooms. Checkpoints that limit the movement of Muslims are often outfitted with facial-recognition devices to vacuum up the population’s biometric data. As China seeks to export its suite of surveillance tech around the world, Xinjiang is a kind of R&D incubator, with the local Muslim population serving as guinea pigs in a laboratory for the deprivation of human rights.

Derek Thompson

As Ian Welsh points out, surveillance states usually involve us in the West pointing towards places like China and shaking our heads. However, if you step back a moment and remember that societies like the US and UK are becoming more unequal over time, then perhaps we're the ones who should be worried:

The endgame, as I’ve been pointing out for years, is a society in which where you are and what you’re doing, and have done is, always known, or at least knowable. And that information is known forever, so the moment someone with power wants to take you out, they can go back thru your life in minute detail. If laws or norms change so that what was OK 10 or 30 years ago isn’t OK now, well they can get you on that.

Ian Welsh

As the world becomes more unequal, the position of elites becomes more perilous, hence Silicon Valley billionaires preparing boltholes in New Zealand. Ironically, they're looking for places where they can't be found, while making serious money from providing surveillance technology. Instead of solving the inequality, they attempt to insulate themselves from the effect of that inequality.

A lot of the crazy amounts of money earned in Silicon Valley comes at the price of infringing our privacy. I've spent a long time thinking about quite nebulous concept. It's not the easiest thing to understand when you examine it more closely.

Privacy is usually considered a freedom from rather than a freedom to, as in "freedom from surveillance". The trouble is that there are many kinds of surveillance, and some of these we actively encourage. A quick example: I know of at least one family that share their location with one another all of the time. At the same time, of course, they're sharing it with the company that provides that service.

There's a lot of power in the 'default' privacy settings devices and applications come with. People tend to go with whatever comes as standard. Sidney Fussell writes in The Atlantic that:

Many apps and products are initially set up to be public: Instagram accounts are open to everyone until you lock them... Even when companies announce convenient shortcuts for enhancing security, their products can never become truly private. Strangers may not be able to see your selfies, but you have no way to untether yourself from the larger ad-targeting ecosystem.

Sidney Fussell

Some of us (including me) are willing to trade some of that privacy for more personalised services that somehow make our lives easier. The tricky thing is when it comes to employers and state surveillance. In these cases there are coercive power relationships at play, rather than just convenience.

Ellen Sheng, writing for CNBC explains how employees in the US are at huge risk from workplace surveillance:

In the workplace, almost any consumer privacy law can be waived. Even if companies give employees a choice about whether or not they want to participate, it’s not hard to force employees to agree. That is, unless lawmakers introduce laws that explicitly state a company can’t make workers agree to a technology...

One example: Companies are increasingly interested in employee social media posts out of concern that employee posts could reflect poorly on the company. A teacher’s aide in Michigan was suspended in 2012 after refusing to share her Facebook page with the school’s superintendent following complaints about a photo she had posted. Since then, dozens of similar cases prompted lawmakers to take action. More than 16 states have passed social media protections for individuals.

Ellen Sheng

It's not just workplaces, though. Schools are hotbeds for new surveillance technologies, as Benjamin Herold notes in an article for Education Week:

Social media monitoring companies track the posts of everyone in the areas surrounding schools, including adults. Other companies scan the private digital content of millions of students using district-issued computers and accounts. Those services are complemented with tip-reporting apps, facial-recognition software, and other new technology systems.

[...]

While schools are typically quiet about their monitoring of public social media posts, they generally disclose to students and parents when digital content created on district-issued devices and accounts will be monitored. Such surveillance is typically done in accordance with schools’ responsible-use policies, which students and parents must agree to in order to use districts’ devices, networks, and accounts.

Benjamin Herold

Hypothetically, students and families can opt out of using that technology. But doing so would make participating in the educational life of most schools exceedingly difficult.

In China, of course, a social credit system makes all of this a million times worse, but we in the West aren't heading in a great direction either.

We're entering a time where, by the time my children are my age, companies, employers, and the state could have decades of data from when they entered the school system through to them finding jobs, and becoming parents themselves.

There are upsides to all of this data, obviously. But I think that in the midst of privacy-focused conversations about Amazon's smart speakers and Google location-sharing, we might be missing the bigger picture around surveillance by educational institutions, employers, and governments.

Returning to Ian Welsh to finish up, remember that it's the coercive power relationships that make surveillance a bad thing:

Surveillance societies are sterile societies. Everyone does what they’re supposed to do all the time, and because we become what we do, it affects our personalities. It particularly affects our creativity, and is a large part of why Communist surveillance societies were less creative than the West, particularly as their police states ramped up.

Ian Welsh

We don't want to think about all of this, though, do we?

Also check out:

Only thoughts conceived while walking have any value

Philosopher and intrepid walker Friedrich Nietzsche is well known for today's quotation-as-title. Fellow philosopher Immanuel Kant was a keen walker, too, along with Henry David Thoreau. There's just something about big walks and big thoughts.

I spent a good part of yesterday walking about 30km because I woke wanting to see the sea. It has a calming effect on me, and my wife was at work with the car. Forty-thousand steps later, I'd not only succeeded in my mission and taken the photo that accompanies this post, but managed to think about all kinds of things that definitely wouldn't have entered my mind had I stayed at home.

I want to focus the majority of this article on a single piece of writing by Craig Mod, whose walk across Japan I followed by SMS. Instead of sharing the details of his 620 mile, six-week trek via social media, he instead updated a server which then sent text messages (with photographs, so technically MMS) to everyone who'd signed up to receive them. Readers could reply, but he didn't receive these until he'd finished the walk and they'd been automatically curated into a book and sent to him.

Writing in WIRED, Mod talks of his "glorious, almost-disconnected walk" which was part experiment, part protest:

I have configured servers, written code, built web pages, helped design products used by millions of people. I am firmly in the camp that believes technology is generally bending the world in a positive direction. Yet, for me, Twitter foments neurosis, Facebook sadness, Google News a sense of foreboding. Instagram turns me covetous. All of them make me want to do it—whatever “it” may be—for the likes, the comments. I can’t help but feel that I am the worst version of myself, being performative on a very short, very depressing timeline. A timeline of seconds.

[...]

So, a month ago, when I started walking, I decided to conduct an experiment. Maybe even a protest. I wanted to test hypotheses. Our smartphones are incredible machines, and to throw them away entirely feels foolhardy. The idea was not to totally disconnect, but to test rational, metered uses of technology. I wanted to experience the walk as the walk, in all of its inevitably boring walkiness. To bask in serendipitous surrealism, not just as steps between reloading my streams. I wanted to experience time.

Craig Mod

I love this, it's so inspiring. The most number of consecutive days I've walked is only two, so I can't even really imagine what it must be like to walk for weeks at a time. It's a form of meditation, I suppose, and a way to re-centre oneself.

The longness of an activity is important. Hours or even days don’t really cut it when it comes to long. “Long” begins with weeks. Weeks of day-after-day long walking days, 30- or 40-kilometer days. Days that leave you wilted and aware of all the neglect your joints and muscles have endured during the last decade of sedentary YouTubing.

[...]

In the context of a walk like this, “boredom” is a goal, the antipode of mindless connectivity, constant stimulation, anger and dissatisfaction. I put “boredom” in quotes because the boredom I’m talking about fosters a heightened sense of presence. To be “bored” is to be free of distraction.

Craig Mod

I find that when I walk for any period of time, certain songs start going through my head. Yesterday, for example, my brain put on repeat the song Good Enough by Dodgy from their album Free Peace Sweet. The time before it was We Can Do It from Jamiroquai's latest album Automaton. I'm not sure where it comes from, although the beat does have something to do with my pace.

Walking by oneself seems to do something to the human brain akin to unlocking the subconscious. That's why I'm not alone in calling it a 'meditative' activity. While I enjoy walking with others, the brain seems to start working a different way when you're by yourself being propelled by your own two legs.

It's easy to feel like we're not 'keeping up' with work, with family and friends, and with the news. The truth is, however, that the most important person to 'keep up' with is yourself. Having a strong sense of self, I believe, is the best way to live a life with meaning.

It might sound 'boring' to go for a long walk, but as Alain de Botton notes in The News: a user's manual, getting out of our routine is sometimes exactly what we need:

What we colloquially call 'feeling bored' is just the mind, acting out of a self-preserving reflex, ejecting information it has despaired of knowing where to place.

Alain de Botton

I'm not going to tell you what I thought about during my walk today as, outside of the rich (inner and outer) context in which the thinking took place, whatever I write would probably sound banal.

To me, however, the thoughts I had today will, like all of the thoughts I've had while doing some serious walking, help me organise my future actions. Perhaps that's what Nietzsche meant when he said that only thoughts conceived while walking have any value.

Also check out:

Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving

Thanks to Einstein for today's quote-as-title. Having once again witnessed the joy of electric scooters in Lisbon recently, I thought I'd look at this trend of 'micromobility'.

Let's begin with Horace Dediu, who explains the term:

Simply, Micromobility promises to have the same effect on mobility as microcomputing had on computing. Bringing transportation to many more and allowing them to travel further and faster. I use the term micromobility precisely because of the connotation with computing and the expansion of consumption but also because it focuses on the vehicle rather than the service. The vehicle is small, the service is vast.

Horace Dediu

Micromobility covers mainly electric scooters and (e-)bikes, which can be found in many of the cities I've visited over the past year. Not in the UK, though, where riding electric scooters is technically illegal. Why? Because of a 183 year-old law, explains Jeff Parsons Metro:

You can’t ride scooters on the road, because the DVLA requires that electric vehicles be registered and taxed. And you can’t ride scooters on the pavement because of the 1835 Highways Act that prohibits anyone from riding a ‘carriage’ on the pavement.

Jeff Parsons

It's only a matter of time, though, before legislation is passed to remove this anachronism. And, to be honest, I can't imagine the police with their stretched resources pulling over anyone who's using one sensibly.

Electric scooters in particular are great and, if you haven't tried one, you should. Florent Crivello, one of Uber's product managers, explains why they're not just fun, but actually valuable:

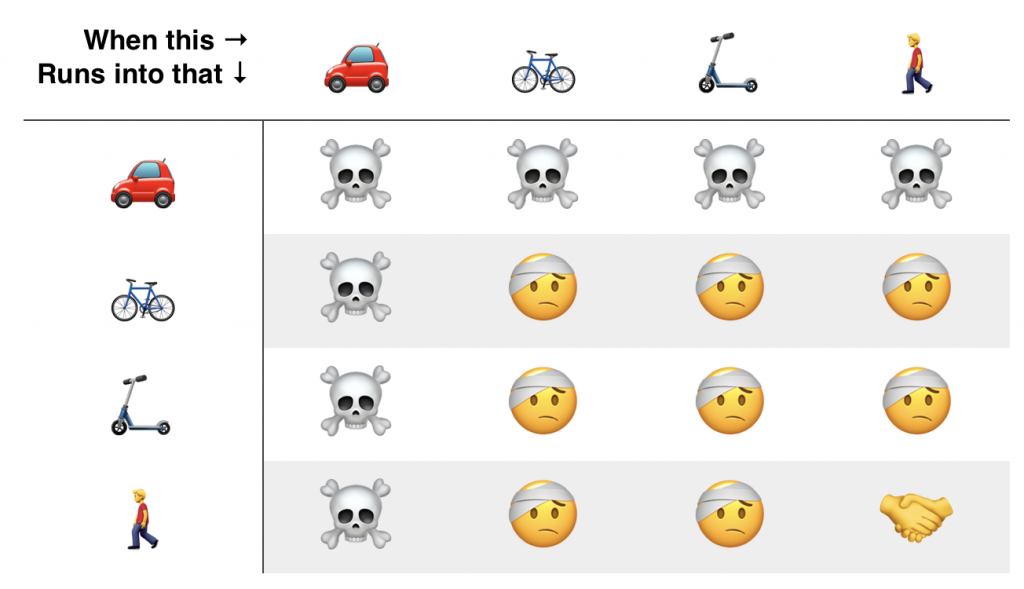

You might be wondering about the third one of these, as I was. Crivello includes this chart:

Of course, as he points out, you can prevent cars running into scooters, bikes, and pedestrians by building separate lanes for them, with a high kerb in between. Countries that have done this, like the Netherlands, have seen a sharp decline in fatalities and injuries.

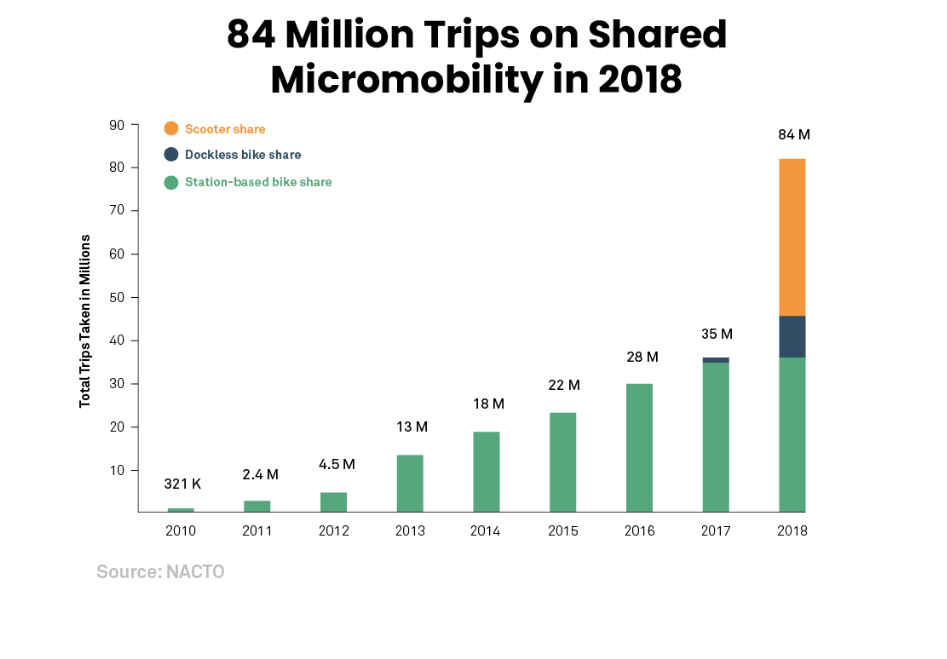

Despite the title, I'm focusing on electric scooters because of my enthusiasm for them and because of the huge growth since they became a thing about 18 months ago. Just look at this chart that Megan Rose Dickey includes in a recent TechCrunch article:

One of the biggest downsides to electric scooters at the moment, and one which threatens the whole idea of 'micromobility' is over-supply. As this photograph in an article by Alan Taylor for The Atlantic shows, this can quickly get out-of-hand when VC-backed companies are involved:

This can scare cities, who don't know how to deal with these kinds of potential consequences. That's why it's refreshing to see Charlotte in North Carolina lead the way by partnering with Passport, a transportation logistics company. As John R. Quain reports for Digital Trends:

“When e-scooters first came to town,” said Charlotte’s city manager Marcus Jones, “it left our shared bike program in the dust.”

[...]

By tracking scooter rentals and coordinating it with other information about public transit routes, congestion, and parking information, Passport can report on where scooters and bikes tend to be idle, where they get the most use, and how they might be deployed to serve more people. Furthermore, rather than railing against escooters, such information can help a city encourage proper use and behavior.

John R. Quain

I'm really quite excited about e-scooters, and can't wait until I can buy and use one legally in the UK!

Also check out:

Sometimes even to live is an act of courage

Thank you to Seneca for the quotation for today's title, which sprang to mind after reading Rosie Spinks' claim in Quartz that we've reached 'peak influencer'.

Where once the social network was basically lunch and sunsets, it’s now a parade of strategically-crafted life updates, career achievements, and public vows to spend less time online (usually made by people who earn money from social media)—all framed with the carefully selected language of a press release. Everyone is striving, so very hard.

Thank goodness for that. The selfie-obsessed influencer brigade is an insidious effect of the neoliberalism that permeates western culture:

For the internet influencer, everything from their morning sun salutation to their coffee enema (really) is a potential money-making opportunity. Forget paying your dues, or working your way up—in fact, forget jobs. Work is life, and getting paid to live your best life is the ultimate aspiration.

[...]

“Selling out” is not just perfectly OK in the influencer economy—it’s the raison d’etre. Influencers generally do not have a craft or discipline to stay loyal to in the first place, and by definition their income comes from selling a version of themselves.

As Yascha Mounk, writing in The Atlantic, explains the problem isn't necessarily with social networks. It's that you care about them. Social networks flatten everything into a never-ending stream. That stream makes it very difficult to differentiate between gossip and (for example) extremely important things that are an existential threat to democratic institutions:

“When you’re on Twitter, every controversy feels like it’s at the same level of importance,” one influential Democratic strategist told me. Over time, he found it more and more difficult to tune Twitter out: “People whose perception of reality is shaped by Twitter live in a different world and a different country than those off Twitter.”

It's easier for me to say these days that our obsession with Twitter and Instagram is unhealthy. While I've never used Instagram (because it's owned by Facebook) a decade ago I was spending hours each week on Twitter. My relationship with the service has changed as I've grown up and it has changed — especially after it became a publicly-traded company in 2013.

Twitter, in particular, now feels like a neverending soap opera similar to EastEnders. There's always some outrage or drama running. Perhaps it's better, as Catherine Price suggests in The New York Times, just to put down our smartphones?

Until now, most discussions of phones’ biochemical effects have focused on dopamine, a brain chemical that helps us form habits — and addictions. Like slot machines, smartphones and apps are explicitly designed to trigger dopamine’s release, with the goal of making our devices difficult to put down.

This manipulation of our dopamine systems is why many experts believe that we are developing behavioral addictions to our phones. But our phones’ effects on cortisol are potentially even more alarming.Cortisol is our primary fight-or-flight hormone. Its release triggers physiological changes, such as spikes in blood pressure, heart rate and blood sugar, that help us react to and survive acute physical threats.

Depending on how we use them, social networks can stoke the worst feelings in us: emotions such as jealousy, anger, and worry. This is not conducive to healthy outcomes, especially for children where stress has a direct correlation to the take-up of addictive substances, and to heart disease in later life.

I wonder how future generations will look back at this time period?

Also check out:

Anything invented after you're thirty-five is against the natural order of things

I'm fond of the above quotation by Douglas Adams that I've used for the title of this article. It serves as a reminder to myself that I've now reached an age when I'll look at a technology and wonder: why?

Despite this, I'm quite excited about the potential of two technologies that will revolutionise our digital world both in our homes and offices and when we're out-and-about. Those technologies? Wi-Fi 6, as it's known colloquially, and 5G networks.

Let's take Wi-Fi 6 first, which Chuong Nguyen explains in an article for Digital Trends, isn't just about faster speeds:

A significant advantage for Wi-Fi 6 devices is better battery life. Though the standard promotes Internet of Things (IoT) devices being able to last for weeks, instead of days, on a single charge as a major benefit, the technology could even prove to be beneficial for computers, especially since Intel’s latest 9th-generation processors for laptops come with Wi-Fi 6 support.

Likewise, Alexis Madrigal, writing in The Atlantic, explains that mobile 5G networks bring benefits other than streaming YouTube videos at ever-higher resolutions, but are quite a technological hurdle:

The fantastic 5G speeds require higher-frequency, shorter-wavelength signals. And the shorter the wavelength, the more likely it is to be blocked by obstacles in the world.

[...]

Ideally, [mobile-associated companies] would like a broader set of customers than smartphone users. So the companies behind 5G are also flaunting many other applications for these networks, from emergency services to autonomous vehicles to every kind of “internet of things” gadget.

If you've been following the kerfuffle around the UK using Huawei's technology for its 5G infrastructure, you'll already know about the politics and security issues at stake here.

Sue Halpern, writing in The New Yorker, outlines the claimed benefits:

Two words explain the difference between our current wireless networks and 5G: speed and latency. 5G—if you believe the hype—is expected to be up to a hundred times faster. (A two-hour movie could be downloaded in less than four seconds.) That speed will reduce, and possibly eliminate, the delay—the latency—between instructing a computer to perform a command and its execution. This, again, if you believe the hype, will lead to a whole new Internet of Things, where everything from toasters to dog collars to dialysis pumps to running shoes will be connected. Remote robotic surgery will be routine, the military will develop hypersonic weapons, and autonomous vehicles will cruise safely along smart highways. The claims are extravagant, and the stakes are high. One estimate projects that 5G will pump twelve trillion dollars into the global economy by 2035, and add twenty-two million new jobs in the United States alone. This 5G world, we are told, will usher in a fourth industrial revolution.

But greater speeds and lower latency isn't all upside for all members of societies, as I learned in this BBC Beyond Today podcast episode about Korean spy cam porn. Halpern explains:

In China, which has installed three hundred and fifty thousand 5G relays—about ten times more than the United States—enhanced geolocation, coupled with an expansive network of surveillance cameras, each equipped with facial-recognition technology, has enabled authorities to track and subordinate the country’s eleven million Uighur Muslims. According to the Times, “the practice makes China a pioneer in applying next-generation technology to watch its people, potentially ushering in a new era of automated racism.”

Automated racism, now there's a thing. It turns out that technologies amplify our existing prejudices. Perhaps we should be a bit more careful and ask more questions before we march down the road of technological improvements? Especially given 5G could affect our ability to predict major storms. I'm reading Low-tech Magazine: The Printed Website at the moment, and it's pretty eye-opening about what we could be doing instead.

Also check out:

Things that people think are wrong (but aren't)

I've collected a bunch of diverse articles that seem to be around the topic of things that people think are wrong, but aren't really. Hence the title.

I'll start with something that everyone over a certain age seems to have a problem with, except for me: sleep. BBC Health lists five sleep myths:

My smartband regularly tells me that I sleep better than 93% of people, and I think that's because of how much I prioritise sleep. I've also got a system, which I've written about before for the times when I do have a rough night.

I like routine, but I also like mixing things up, which is why I appreciate chunks of time at home interspersed with travel. Oliver Burkeman, writing in The Guardian, suggests, however, that routines aren't the be-all and end-all:

Some people are so disorganised that a strict routine is a lifesaver. But speaking as a recovering rigid-schedules addict, trust me: if you click excitedly on each new article promising the perfect morning routine, you’re almost certainly not one of those people. You’re one of the other kind – people who’d benefit from struggling less to control their day, responding a bit more intuitively to the needs of the moment. This is the self-help principle you might call the law of unwelcome advice: if you love the idea of implementing a new technique, it’s likely to be the opposite of what you need.

Expecting something new to solve an underlying problem is a symptom of our culture's focus on the new and novel. While there's so much stuff out there we haven't experienced, should we spend our lives seeking it out to the detriment of the tried and tested, the things that we really enjoy?

On the recommendation of my wife, I recently listened to a great episode of the Off Menu podcast featuring Victoria Cohen Mitchell. It's not only extremely entertaining, but she mentions how, for her, a nice Ploughman's lunch is better than some fancy meal.

This brings me to an article in The Atlantic by Joe Pinsker, who writes that kids who watch and re-watch the same film might be on to something:

In general, psychological and behavioral-economics research has found that when people make decisions about what they think they’ll enjoy, they often assign priority to unfamiliar experiences—such as a new book or movie, or traveling somewhere they’ve never been before. They are not wrong to do so: People generally enjoy things less the more accustomed to them they become. As O’Brien [professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business] writes, “People may choose novelty not because they expect exceptionally positive reactions to the new option, but because they expect exceptionally dull reactions to the old option.” And sometimes, that expected dullness might be exaggerated.

So there's something to be said for re-reading novels you read when you were younger instead of something shortlisted for a prize, or discounted in the local bookshop. I found re-reading Dostoevsky's Crime & Punishment recently exhilarating as I probably hadn't ready it since I became a parent. Different periods of your life put different spins on things that you think you already know.

Also check out:

Murmurations

Starlings where I live in Northumberland, England, also swarm like this, but not in so many numbers.

I love the way that we give interesting names to groups of animals English (e.g. a ‘murder’ of crows). There’s a whole list of them on Wikipedia.

Source: The Atlantic

The link between sleep and creativity

I’m a big fan of sleep. Since buying a smartwatch earlier this year, I’ve been wearing it all of the time, including in bed at night. What I’ve found is that I’m actually a good sleeper, regularly sleeping better than 95% of other people who use the same Mi Fit app.

Like most people, after a poor night’s sleep I’m not at my best the next day. This article by Ed Yong in The Atlantic helps explain why.

As you start to fall asleep, you enter non-REM sleep. That includes a light phase that takes up most of the night, and a period of much heavier slumber called slow-wave sleep, or SWS, when millions of neurons fire simultaneously and strongly, like a cellular Greek chorus. “It’s something you don’t see in a wakeful state at all,” says Lewis. “You’re in a deep physiological state of sleep and you’d be unhappy if you were woken up.”We’ve known for generations that, if we’ve got a problem to solve or a decision to make, that it’s a good idea to ‘sleep on it’. Science is catching up with folk wisdom.During that state, the brain replays memories. For example, the same neurons that fired when a rat ran through a maze during the day will spontaneously fire while it sleeps at night, in roughly the same order. These reruns help to consolidate and strengthen newly formed memories, integrating them into existing knowledge. But Lewis explains that they also help the brain extract generalities from specifics—an idea that others have also supported.

The other phase of sleep—REM, which stands for rapid eye movement—is very different. That Greek chorus of neurons that sang so synchronously during non-REM sleep descends into a cacophonous din, as various parts of the neocortex become activated, seemingly at random. Meanwhile, a chemical called acetylcholine—the same one that Loewi identified in his sleep-inspired work—floods the brain, disrupting the connection between the hippocampus and the neocortex, and placing both in an especially flexible state, where connections between neurons can be more easily formed, strengthened, or weakened.The difficulty is that our sleep quality is affected by blue light confusing the brain as to what kind of day it is. That's why we're seeing increasing numbers of devices changing your screen colour towards the red end of the spectrum in the evening. If you have disrupted sleep, you miss out on an important phase of your sleep cycle.

Crucially, they build on one another. The sleeping brain goes through one cycle of non-REM and REM sleep every 90 minutes or so. Over the course of a night—or several nights—the hippocampus and neocortex repeatedly sync up and decouple, and the sequence of abstraction and connection repeats itself. “An analogy would be two researchers who initially work on the same problem together, then go away and each think about it separately, then come back together to work on it further,” Lewis writes.As the article states, there’s further research to be done here. But, given that sleep (along with exercise and nutrition) is one of the three ‘pillars’ of productivity, this certainly chimes with my experience.“The obvious implication is that if you’re working on a difficult problem, allow yourself enough nights of sleep,” she adds. “Particularly if you’re trying to work on something that requires thinking outside the box, maybe don’t do it in too much of a rush.”

Source: The Atlantic