- How does a computer ‘see’ gender? (Pew Research Center) — "Machine learning tools can bring substantial efficiency gains to analyzing large quantities of data, which is why we used this type of system to examine thousands of image search results in our own studies. But unlike traditional computer programs – which follow a highly prescribed set of steps to reach their conclusions – these systems make their decisions in ways that are largely hidden from public view, and highly dependent on the data used to train them. As such, they can be prone to systematic biases and can fail in ways that are difficult to understand and hard to predict in advance."

- The Communication We Share with Apes (Nautilus) — "Many primate species use gestures to communicate with others in their groups. Wild chimpanzees have been seen to use at least 66 different hand signals and movements to communicate with each other. Lifting a foot toward another chimp means “climb on me,” while stroking their mouth can mean “give me the object.” In the past, researchers have also successfully taught apes more than 100 words in sign language."

- Why degrowth is the only responsible way forward (openDemocracy) — "If we free our imagination from the liberal idea that well-being is best measured by the amount of stuff that we consume, we may discover that a good life could also be materially light. This is the idea of voluntary sufficiency. If we manage to decide collectively and democratically what is necessary and enough for a good life, then we could have plenty."

- 3 times when procrastination can be a good thing (Fast Company) — "It took Leonardo da Vinci years to finish painting the Mona Lisa. You could say the masterpiece was created by a master procrastinator. Sure, da Vinci wasn’t under a tight deadline, but his lengthy process demonstrates the idea that we need to work through a lot of bad ideas before we get down to the good ones."

- Why can’t we agree on what’s true any more? (The Guardian) — "What if, instead, we accepted the claim that all reports about the world are simply framings of one kind or another, which cannot but involve political and moral ideas about what counts as important? After all, reality becomes incoherent and overwhelming unless it is simplified and narrated in some way or other.

- A good teacher voice strikes fear into grown men (TES) — "A good teacher voice can cut glass if used with care. It can silence a class of children; it can strike fear into the hearts of grown men. A quiet, carefully placed “Excuse me”, with just the slightest emphasis on the “-se”, is more effective at stopping an argument between adults or children than any amount of reason."

- Freeing software (John Ohno) — "The only way to set software free is to unshackle it from the needs of capital. And, capital has become so dependent upon software that an independent ecosystem of anti-capitalist software, sufficiently popular, can starve it of access to the speed and violence it needs to consume ever-doubling quantities of to survive."

- Young People Are Going to Save Us All From Office Life (The New York Times) — "Today’s young workers have been called lazy and entitled. Could they, instead, be among the first to understand the proper role of work in life — and end up remaking work for everyone else?"

- Global climate strikes: Don’t say you’re sorry. We need people who can take action to TAKE ACTUAL ACTION (The Guardian) — "Brenda the civil disobedience penguin gives some handy dos and don’ts for your civil disobedience"

- Flexible working is possible if schools focus on outcomes, not hours (TES) — "Children deserve access to experienced, specialist teachers at a time when they are needed most. To achieve this we need a step change. We need to drive a culture shift in the education community to make teaching more family-friendly."

- Why Constant Learners All Embrace the 5-Hour Rule (Inc.) — "Franklin's five-hour rule reflects the very simple idea that, over time, the smartest and most successful people are the ones who are constant and deliberate learners."

- This App Helps You Learn a New Language With Music (Geek.com) — "Okay, they don’t literally use “Baby Shark,” but Earworms MBT can teach you Spanish, Italian, German, and French and is great for common situations like getting directions, taking a taxi, or going to a restaurant."

- “What’s on your mind?”

- “And what else?”

- “What’s the real challenge here for you?”

- “What do you want?”

- “How can I help?”

- “If you say yes to this, what must you say no to?”

- “What was most useful or most valuable here for you?”

- Join forces with a known legacy brand

- Apply for a posted position

- Independent Consultant: hometown hero variety

- Independent Consultant: free agent variety

Everyone has something to teach

As someone who is apparently in a microgeneration between Generation X and Millennials, I feel constantly the tension between the “old ways” of doing things and the “throwing things against the wall to see what sticks” approach.

This article frames the issue nicely: everyone has something to teach, no matter whether you’re the person with lots of experience to share, or the person with the new approach.

Gaining experience takes time, effort, and often comes at the price of making painful mistakes. You don’t want to let those lessons go. You want them to mean something, to help you from making the same painful mistakes again. To help others from making the same mistakes you made. So it will always be the case that those with the most experience – and the good, smart, accurate wisdom that comes from it – will be the least willing to adapt their views as the world evolves.Source: Experts From A World That No Longer Exists · Collaborative FundNeither should be the case, because every generation cycles through the same process. Today’s older generation once understood the world better than their parents, who scoffed at them. Today’s younger generation will one day be stuck in the antiquated norms of their past, and their kids will scoff at them. I can imagine my son in 80 years screaming, “Get off my metaverse lawn!”

One takeaway from this is that no age has a monopoly on insight, and different levels of experience offer different kinds of lessons. Vishal Khandelwal recently wrote that old guys don’t understand tech, but young guys don’t understand risk. Another way to put it is: everyone has something to teach.

Image: CC BY Tea, two sugars

Face-to-face university classes during a pandemic? Why?

Earlier in my career, when I worked for Jisc, I was based at Northumbria University in Newcastle. It's just been announced that 770 students there have been infected with COVID-19.

As Lorna Finlayson, a philosophy lecturer at the University of Essex, points out, the desire to get students on campus for face-to-face teaching is driven by economics. Universities are businesses, and some of them are likely to fail this academic year.

[A]fter years of pushing to expand online learning and “lecture capture” on the basis that it is what students want, university managers have decided that what students really want now, during a global pandemic, is face-to-face contact. This sudden-onset fetish reached its most perverse extreme in the case of Boston University, which, realising that many teaching rooms lack good ventilation or even windows, decided to order “giant air circulators”, only to discover that the air circulators were very noisy. Apparently unable to source enough “mufflers” for the air circulators, the university ordered Bluetooth headsets to enable students and teachers to communicate over the roar of machinery.

All of which raises the question: why? The determination to bring students back to campus at any cost doesn’t stem from a dewy-eyed appreciation of in-person pedagogy, nor from concerns about the impact of isolation on students’ mental health. If university managers had any interest in such things, they would not have spent years cutting back on study skills support and counselling services.

Lorna Finlayson, How universities tricked students into returning to campus (The Guardian)

I know people who work in universities in various positions. What they tell me astounds me; a callous disregard for human life in the pursuit of either economic survival, or profit.

This is, as usual, all about the money. With student fees and rents now their main source of revenue, universities will do anything to recruit and retain. When the pandemic hit, university managers warned of a potentially catastrophic loss of income from international student fees in particular. Many used this as an excuse to cut jobs and freeze pay, even as vice-chancellors and senior management continued to rake in huge salaries. As it turned out, international student admissions reached a record high this year, with domestic undergraduate numbers also up – perhaps less due to the irresistibility of universities’ “offer” than to the lack of other options (needless to say, staff jobs and pay have yet to be reinstated).

Lorna Finlayson, How universities tricked students into returning to campus (The Guardian)

But students are more than just fee-payers. They are rent-payers too. Rightly or wrongly, most of those in charge of universities have assumed that only the promise of face-to-face classes would tempt students back to their accommodation. That promise can be safely broken only once rental contracts are signed and income streams flowing.

I predict legal action at some point in the near future.

Saturday seductions

Having a Bank Holiday in the UK on a Friday has really thrown me this week. So apologies for this link roundup being a bit later than usual...

I do try to inject a little bit of positivity into these links every week, but the past few days have made me a little concerned about our post-pandemic future. Anyway, here goes...

Radio Garden

This popped up in my Twitter feed this week and brought joy to my life. So simple but so effective: either randomly go to, or browse radio stations around the world. The one featured in the screenshot above is one close to me I forgot existed!

COVID and forced experiments

Every time we get a new kind of tool, we start by making the new thing fit the existing ways that we work, but then, over time, we change the work to fit the new tool. You’re used to making your metrics dashboard in PowerPoint, and then the cloud comes along and you can make it in Google Docs and everyone always has the latest version. But one day, you realise that the dashboard could be generated automatically and be a live webpage, and no-one needs to make those slides at all. Today, sometimes doing the meeting as a video call is a poor substitute for human interaction, but sometimes it’s like putting the slides in the cloud.

I don’t think we can know which is which right now, but we’re going through a vast, forced public experiment to find out which bits of human psychology will align with which kinds of tool, just as we did with SMS, email or indeed phone calls in previous generations.

Benedict Evans

An interesting post that both invokes 'green eggs and ham' as a metaphor, and includes an anecdote from an Ofcom report towards the end about a woman named Polly that no-one who does training or usability testing should ever forget.

Education is over…

What future learning environments need is not more mechanization, but more humanization; not more data, but more wisdom; not more

William Rankin (regenerative.global)

objectification, but more subjectification; not more Plato, but more Aristotle.

I agree, although 'subjectification' is a really awkward word that suggests school subjects, which isn't the author's point. After all of this, I can't see parents, in particular, accepting going back to how school has been. At least, I hope not.

What Happens Next?

This guide... is meant to give you hope and fear. To beat COVID-19 in a way that also protects our mental & financial health, we need optimism to create plans, and pessimism to create backup plans. As Gladys Bronwyn Stern once said, “The optimist invents the airplane and the pessimist the parachute.”

Marcel Salathé & Nicky Case

Modelling what happens next in terms of lockdowns, etc. is not an easy think to understand, and there are many competing opinions. This guide, with 'playable simulations' is the best thing I've seen so far, and I feel I'm much better prepared for the next decade (yes, you read that correctly).

Sheltering in Place with Montaigne

By the time Michel de Montaigne wrote “Of Experience,” the last entry in his third and final book of essays, the French statesman and author had weathered numerous outbreaks of plague (in 1585, while he was mayor of Bordeaux, a third of the population perished), political uprisings, the death of five daughters, and an onslaught of physical ailments, from rotting teeth to debilitating kidney stones.

[...]

The ubiquity of suffering heightened Montaigne’s attentiveness to the complexity of human experience. Pleasure, he contends, flows not from free rein but structure. The brevity of existence, he goes on, gives it a certain heft. Exertion, truth be told, is the best form of compensation. Time is slippery, the more reason to grab hold.

Drew Bratcher (The Paris Review)

Montaigne is one of my favourite authors, and having recently read Stefan Zweig's bioraphy of him, he feels even more relevant to our times.

Clarity for Teachers: Day 42

There’s a children’s book that I love, The Greentail Mouse by Leo Lionni. It plays on the old theme of the town mouse and the country mouse. In this telling, the town mouse comes to visit his cousins in their rural idyll, and they ask him about life in the town. It’s horrible, he says, noisy and dangerous, but there is one day a year when it’s amazing, and that’s when carnival comes around. So the country mice decide to hold a carnival of their own: they make costumes and masks, they grunt and shriek and howl and jump around like wild things. But then, at some point, they forget that they are wearing masks; they end up believing that they are the fierce creatures they have been playing at being, and their formerly peaceful community becomes filled with fear, hatred and suspicion.

Dougald Hine

Dougald Hine is taking Charlie Davies' course Clarity for Teachers and is blogging each day about it. This is from the last post in the series. I'm including it partly to point towards Homeward Bound, which I've just signed up for, and which starts next Thursday.

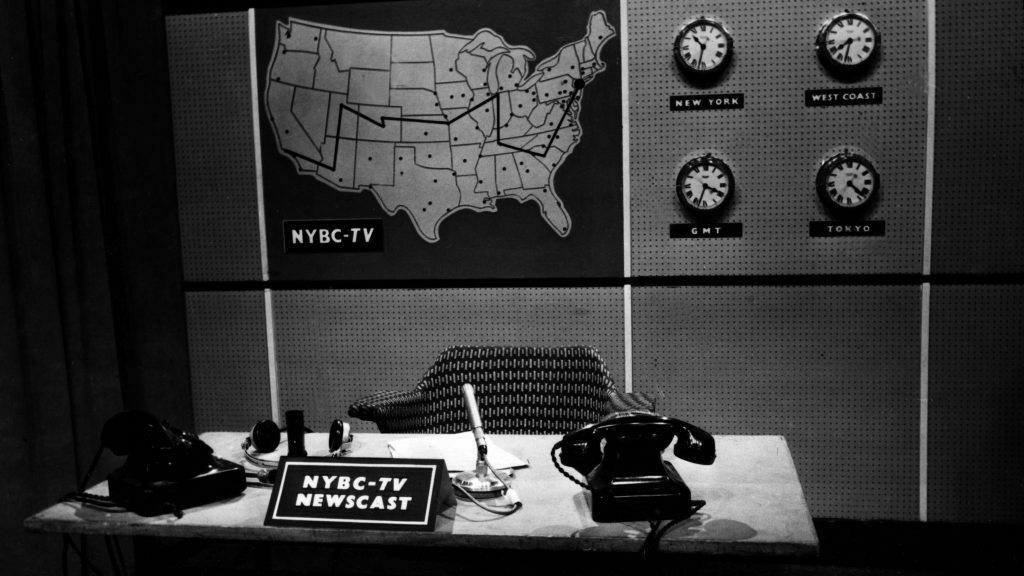

BBC Archive: Empty sets

Give your video calls a makeover, with this selection of over 100 empty sets from the BBC Archive.

Who hasn't wanted to host a pub quiz from the Queen Vic, conduct a job interview from the confines of Fletch's cell, or catch up with friends and family from the bridge of the Liberator in Blake's 7?

I love this idea, to spice up Zoom calls, etc.

People you follow

First I search for my new item of interest, then I filter the results by “People I Follow.” (You can try it out with some of my recent searches: “Roger Angell,” “Captain Beefheart,” and “Rockford Files.”) Depending on the subject, I might have pages and pages of links, all handily selected for me by people I find interesting.

Austin Kleon

In his most recent newsletter, Austin Kleon referenced this post of his from five years ago. I think the idea is a great one and I'll definitely be doing this in future! Twitter move settings around occasionally, but it's still there under 'search filters'.

68 Bits of Unsolicited Advice

Perhaps the most counter-intuitive truth of the universe is that the more you give to others, the more you’ll get. Understanding this is the beginning of wisdom.

Before you are old, attend as many funerals as you can bear, and listen. Nobody talks about the departed’s achievements. The only thing people will remember is what kind of person you were while you were achieving.

Over the long term, the future is decided by optimists. To be an optimist you don’t have to ignore all the many problems we create; you just have to imagine improving our capacity to solve problems.

Kevin Kelly (The Technium)

The venerable KK is now 68 years of age and so has dispensed some wisdom. It's a mixed bag, but I particularly liked these the three bits of advice I've quoted above.

Header image by Ben Jennings.

Saturday strikings

This week's roundup is going out a day later than usual, as yesterday was the Global Climate Strike and Thought Shrapnel was striking too!

Here's what I've been paying attention to this week:

The school system is a modern phenomenon, as is the childhood it produces

Good old Ivan Illich with today's quotation-as-title. If you haven't read his Deschooling Society yet, you must. Given actions speak louder than words, it really makes you think about what we're actually doing to children when we send them off to the world of formal education.

The pupil is thereby "schooled" to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new.

ivan illich

I left teaching almost a decade ago and still have a strong connection to the classroom through my wife (who's a teacher), my children (who are at school) and my friends/network (many of whom are involved in formal education.

That's why a post entitled The Absurd Structure of High School by Bernie Bleske resonated with me, even though it's based on his experience in the US:

The system’s scheduling fails on every possible level. If the goal is productivity, the fractured nature of the tasks undermines efficient product. So much time is spent in transition that very little is accomplished before there is a demand to move on. If the goal is maximum content conveyed, then the system works marginally well, in that students are pretty much bombarded with detail throughout their school day. However, that breadth of content comes at the cost of depth of understanding. The fractured nature of the work, the short amount of time provided, and the speed of change all undermine learning beyond the superficial. It’s shocking, really, that students learn as much as they do.

Bernie Bleske

We've known for a long time now, that a 'stage, not age' approach is much better for everyone involved. My daughter, sadly, enjoys school but is pretty bored there. And, frustratingly, there's not much we as parents can do about it.

If you've got an academically-able child, on the surface it seems like part of the problem is them being 'held back' by their peers. However, studies show that there's little empirical evidence for this being true — as Oscar Hedstrom points out in Why streaming kids according to ability is a terrible idea:

Despite all this, there is limited empirical evidence to suggest that streaming results in better outcomes for students. Professor John Hattie, director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute, notes that ‘tracking has minimal effects on learning outcomes and profound negative equity effects’. Streaming significantly – and negatively – affects those students placed in the bottom sets. These students tend to have much higher representation of low socioeconomic backgrounds. Less significant is the small benefit for those lucky clever students in the higher sets. The overall result is relative inequality. The smart stay smart, and the dumb get dumber, further entrenching social disadvantage.

Oscar Hedstrom

I worked in a school in a rough area that streamed kids based on the results of a 'literacy skills' test on entry. The result was actually middle-class segregation within the school. As a child myself, I also went to a pretty tough school in an ex-mining town, which was a bit more integrated.

The trouble with all of this is that most of the learning that happens in school is inside some form of classroom. As a recent Innovation Unit report entitled Local Learning Ecosystems: emerging models discusses, 'learning ecosystem' is a bit of a buzz-term at the moment, but with potentially useful applications:

It remains to be seen whether the education ecosystem idea, as expressed in these varieties, will evolve as a truly significant new driver in public education on a large scale. These initiatives reflect ambitious visions well beyond current achievements. Conventional systems, with their excessive assessment routines, pressurized school communities, and entrenched vestigial approaches, are difficult to shift. But this report offers a taste of the creative flourishing in education thinking today that has emerged against, and perhaps in response to, the erosion of resources for public education, often abetted by indifferent, even hostile government.

Local Learning Ecosystems: emerging models

My go-to book around all of this is still Prof. Keri Facer's excellent Learning Futures: education, technology and social change. I still haven't come across another book with such a hopeful, practical vision for the future since reading it when it came out in 2011.

Hopefully, taking a learning ecosystem or 'ecology' approach will provide the necessary shift of perspective to move us to the world beyond (just) classrooms.

Also check out:

Seven coaching questions

Eylan Ezekiel shared this article in the Slack channel we hang out in most days. It’s a useful set of questions for when you’re in a coaching situation — which could be in sports, at work, when teaching, or even parenting:

(Educational) consulting for the uninitiated

Noah Geisel, who I know from the world of Open Badges, has written a great post on how to be an educational consultant. I’ve got some advice of my own to add to his, but I’ll let him set the scene:

In my experience, people in employment who have never been their own boss are always interested at the prospect of becoming a freelancer or consultant. This is particularly the case with jobs like teaching that are endless time and energy pits.I get several messages each month from people — usually teachers — reaching out for an informational interview to learn about what options exist to be an education consultant. I’ve had the conversation enough times now that I’m sharing out this quick primer of what normally gets discussed. Maybe it’ll save you the cup of coffee you were going to buy me or help you come prepared to our coffee with novel questions that really make me think.

Like Noah, the first thing I’d do is try and get underneath the desire to do something different. Why is that? I think he does this brilliantly by asking whether potential consultants are running towards, or running away, from something:

Which way are you running? This is the most important question. Are you running to a new opportunity or are you running away from your current situation? The people I know who are successful and happy doing this work definitely ran to it. The work is just too hard to be anything other than what you want (or even NEED) to be doing. I can’t speak for others but my own experience is that this path is a calling, not an escape pod.I can only speak about my own experience, but once the Open Badges work went outside of Mozilla, and I'd pretty much done all I could with the Web Literacy work, it was time for me to move into consultancy. It was the logical step, both because I was ready for it, but also because people were asking if I was available.

If no-one’s asking if you can help them out with something that you already specialise in, then it’s going to be long, hard struggle to be seen as an expert, get gigs, and pay your mortgage. However, if you do decide to make the leap, I like the way Noah demarcates the types of consultancy you can do:

If you’ve been used to a job where you do lots of different things, such as teaching, the temptation is going to be to offer lots of different services. The trouble with that, of course, is that people find it difficult to know what you’re selling.

One of the best things I've ever done is to set up a co-operative with friends and former colleagues. We have an associated Slack channel for both member discussions (private) and discourse with trusted colleagues and acquaintances. Meeting regularly, and doing work with these guys not only gives us flexibility, but access to a wider range of expertise than I could provide on my own.You are wise to avoid attempting to be all things to all people. Focus on a strength that gives you a competitive advantage and go hard; if you fail, you’ll want to know that wasn’t because you didn’t put enough into it.

As Noah says, it’s great to earn a bit of money on the side, but that’s very different to deciding that your going to rely on products you can sell and services you can provide for your income. I did it successfully for three years, before deciding to take my current four day per week position with Moodle, and work with the co-op on the side.

Finally, one thing that might help is to see your life as have ‘seasons’. I think too many people see their professional life as some kind of ladder which they need to climb. It’s nothing of the sort. It’s always nice to be well-paid (and I’ve never earned more than when I was consulting full-time) but there’s other things that are valuable in life: colleagues, security, and benefits such as a pension and healthcare, to name but a few.

Source: Verses

(Related: a post I wrote of my experiences after two years of full-time consultancy)