- Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive Into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance (EFF)

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (Shoshana Zuboff)

- Zeugma and syllepsis (Wikipedia)

- General Data Protection Regulation (Wikipedia)

- Hierarchy Is Not the Problem (Richard D. Bartlett)

- Instead of breaking up big tech, let’s break them open (Redecentralize)

- Don’t ask forgiveness, radiate intent (Elizabeth Ayer) — "I certainly don’t need a reputation as being underhanded or an organizational problem. Especially as a repeat behavior, signalling builds me a track record of openness and predictability, even as I take risks or push boundaries."

- When will we have flying cars? Maybe sooner than you think. (MIT Technology Review) — "An automated air traffic management system in constant communication with every flying car could route them to prevent collisions, with human operators on the ground ready to take over by remote control in an emergency. Still, existing laws and public fears mean there’ll probably have to be pilots at least for a while, even if only as a backup to an autonomous system."

- For Smart Animals, Octopuses Are Very Weird (The Atlantic) — "Unencumbered by a shell, cephalopods became flexible in both body and mind... They could move faster, expand into new habitats, insinuate their arms into crevices in search of prey."

- Cannabidiol in Anxiety and Sleep: A Large Case Series. (PubMed) — "The final sample consisted of 72 adults presenting with primary concerns of anxiety (n = 47) or poor sleep (n = 25). Anxiety scores decreased within the first month in 57 patients (79.2%) and remained decreased during the study duration. Sleep scores improved within the first month in 48 patients (66.7%) but fluctuated over time. In this chart review, CBD was well tolerated in all but 3 patients."

- 22 Lessons I'm Still Learning at 82 (Coach George Raveling) — "We must always fill ourselves with more questions than answers. You should never retire your mind. After you retire mentally, then you are just taking up residence in society. I do not ever just want to be a resident of society. I want to be a contributor to our communities."

- How Boris Johnson's "model bus hobby" non sequitur manipulated the public discourse and his search results (BoingBoing) — "Remember, any time a politician deliberately acts like an idiot in public, there's a good chance that they're doing it deliberately, and even if they're not, public idiocy can be very useful indeed."

- It’s not that we’ve failed to rein in Facebook and Google. We’ve not even tried. (The Guardian) — "Surveillance capitalism is not the same as digital technology. It is an economic logic that has hijacked the digital for its own purposes. The logic of surveillance capitalism begins with unilaterally claiming private human experience as free raw material for production and sales."

- Choose Boring Technology (Dan McKinley) — "The nice thing about boringness (so constrained) is that the capabilities of these things are well understood. But more importantly, their failure modes are well understood."

- What makes a good excuse? A Cambridge philosopher may have the answer (University of Cambridge) — "Intentions are plans for action. To say that your intention was morally adequate is to say that your plan for action was morally sound. So when you make an excuse, you plead that your plan for action was morally fine – it’s just that something went awry in putting it into practice."

- Your Focus Is Priceless. Stop Giving It Away. (Forge) — "To virtually everyone who isn’t you, your focus is a commodity. It is being amassed, collected, repackaged and sold en masse. This makes your attention extremely valuable in aggregate. Collectively, audiences are worth a whole lot. But individually, your attention and my attention don’t mean anything to the eyeball aggregators. It’s a drop in their growing ocean. It’s essentially nothing."

- Some of your talents and skills can cause burnout. Here’s how to identify them (Fast Company) — "You didn’t mess up somewhere along the way or miss an important lesson that the rest of us received. We’re all dealing with gifts that drain our energy, but up until now, it hasn’t been a topic of conversation. We aren’t discussing how we end up overusing our gifts and feeling depleted over time."

- Learning from surveillance capitalism (Code Acts in Education) — "Terms such as ‘behavioural surplus’, ‘prediction products’, ‘behavioural futures markets’, and ‘instrumentarian power’ provide a useful critical language for decoding what surveillance capitalism is, what it does, and at what cost."

- Facebook, Libra, and the Long Game (Stratechery) — "Certainly Facebook’s audacity and ambition should not be underestimated, and the company’s network is the biggest reason to believe Libra will work; Facebook’s brand is the biggest reason to believe it will not."

- The Pixar Theory (Jon Negroni) — "Every Pixar movie is connected. I explain how, and possibly why."

- Mario Royale (Kottke.org) — "Mario Royale (now renamed DMCA Royale to skirt around Nintendo’s intellectual property rights) is a battle royale game based on Super Mario Bros in which you compete against 74 other players to finish four levels in the top three. "

- Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think (The Atlantic) — "In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s."

- What Happens When Your Kids Develop Their Own Gaming Taste (Kotaku) — "It’s rewarding too, though, to see your kids forging their own path. I feel the same way when I watch my stepson dominate a round of Fortnite as I probably would if he were amazing at rugby: slightly baffled, but nonetheless proud."

- Whence the value of open? (Half an Hour) — "We will find, over time and as a society, that just as there is a sweet spot for connectivity, there is a sweet spot for openness. And that point where be where the default for openness meets the push-back from people on the basis of other values such as autonomy, diversity and interactivity. And where, exactly, this sweet spot is, needs to be defined by the community, and achieved as a consensus."

- How to Be Resilient in the Face of Harsh Criticism (HBR) — "Here are four steps you can try the next time harsh feedback catches you off-guard. I’ve organized them into an easy-to-remember acronym — CURE — to help you put these lessons in practice even when you’re under stress."

- Fans Are Better Than Tech at Organizing Information Online (WIRED) — "Tagging systems are a way of imposing order on the real world, and the world doesn't just stop moving and changing once you've got your nice categories set up."

- Platform avoidance,

- Infrastructural avoidance

- Hardware experiments

- Digital homesteading

Meredith Whittaker on AI doomerism

This interview with Signal CEO Meredith Whittaker in Slate is so awesome. She brings the AI 'doomer' narrative back time and again both to surveillance capitalism, and the massive mismatch between marginalised people currently having harm done to them and the potential harm done to very powerful people.

Source: A.I. Doom Narratives Are Hiding What We Should Be Most Afraid Of | SlateWhat we’re calling machine learning or artificial intelligence is basically statistical systems that make predictions based on large amounts of data. So in the case of the companies we’re talking about, we’re talking about data that was gathered through surveillance, or some variant of the surveillance business model, that is then used to train these systems, that are then being claimed to be intelligent, or capable of making significant decisions that shape our lives and opportunities—even though this data is often very flimsy.

[...]

We are in a world where private corporations have unfathomably complex and detailed dossiers about billions and billions of people, and increasingly provide the infrastructures for our social and economic institutions. Whether that is providing so-called A.I. models that are outsourcing decision-making or providing cloud support that is ultimately placing incredibly sensitive information, again, in the hands of a handful of corporations that are centralizing these functions with very little transparency and almost no accountability. That is not an inevitable situation: We know who the actors are, we know where they live. We have some sense of what interventions could be healthy for moving toward something that is more supportive of the public good.

[...]

My concern with some of the arguments that are so-called existential, the most existential, is that they are implicitly arguing that we need to wait until the people who are most privileged now, who are not threatened currently, are in fact threatened before we consider a risk big enough to care about. Right now, low-wage workers, people who are historically marginalized, Black people, women, disabled people, people in countries that are on the cusp of climate catastrophe—many, many folks are at risk. Their existence is threatened or otherwise shaped and harmed by the deployment of these systems.... So my concern is that if we wait for an existential threat that also includes the most privileged person in the entire world, we are implicitly saying—maybe not out loud, but the structure of that argument is—that the threats to people who are minoritized and harmed now don’t matter until they matter for that most privileged person in the world. That’s another way of sitting on our hands while these harms play out. That is my core concern with the focus on the long-term, instead of the focus on the short-term.

Continuous eloquence is tedious

🏭 Ukraine plans huge cryptocurrency mining data centers next to nuclear power plants — "Ukraine's Energoatom followed up [the May 2020] deal with another partnership in October. The state enterprise announced an MoU with Dutch mining company Bitfury to operate multiple data centers near its four nuclear power plants, with a total mining consumption of 2GW."

It's already impossible to buy graphics cards, due to their GPUs being perfect for crypto mining. That fact doesn't seem like it's going to be resolved anytime soon.

😔 The unbearable banality of Jeff Bezos — "To put it in Freudian terms, we are talking about the triumph of the consumerist id over the ethical superego. Bezos is a kind of managerial Mephistopheles for our time, who will guarantee you a life of worldly customer ecstasy as long as you avert your eyes from the iniquities being carried out in your name."

I've started buying less stuff from Amazon; even just removing the app from my phone has made them treat me as just another online shop. I also switched a few years ago from a Kindle to a ePub-based e-reader.

📱 The great unbundling — "Covid brought shock and a lot of broken habits to tech, but mostly, it accelerates everything that was already changing. 20 trillion dollars of retail, brands, TV and advertising is being overturned, and software is remaking everything from cars to pharma. Meanwhile, China has more smartphone users than Europe and the USA combined, and India is close behind - technology and innovation will be much more widely spread. For that and lots of other reasons, tech is becoming a regulated industry, but if we step over the slogans, what does that actually mean? Tech is entering its second 50 years."

This is a really interesting presentation (and slide deck). It's been interesting watching Evans build this iteratively over the last few weeks, as he's been sharing his progress on Twitter.

🗯️ The Coup We Are Not Talking About — "In an information civilization, societies are defined by questions of knowledge — how it is distributed, the authority that governs its distribution and the power that protects that authority. Who knows? Who decides who knows? Who decides who decides who knows? Surveillance capitalists now hold the answers to each question, though we never elected them to govern. This is the essence of the epistemic coup. They claim the authority to decide who knows by asserting ownership rights over our personal information and defend that authority with the power to control critical information systems and infrastructures."

Zuboff is an interesting character, and her book on surveillance capitalism is a classic. This might article be a little overblown, but it's still an important subject for discussion.

☀️ Who Built the Egyptian Pyramids? Not Slaves — "So why do so many people think the Egyptian pyramids were built by slaves? The Greek historian Herodotus seems to have been the first to suggest that was the case. Herodotus has sometimes been called the “father of history.” Other times he's been dubbed the “father of lies.” He claimed to have toured Egypt and wrote that the pyramids were built by slaves. But Herodotus actually lived thousands of years after the fact."

It's always good to challenge our assumptions, and, perhaps more importantly, analyse why we came to hold them in the first place.

Quotation-as-title by Blaise Pascal. Image by Victor Forgacs.

Microcast #086 — Strategies for dealing with surveillance capitalism

Over the last year (at least) I've been talking about the dangers of surveillance capitalism. Stephen Haggard picked up on this and, after an email conversation, sent through an audio provocation for disucssion.

If you'd like to join this discussion, feel free to comment on this microcast, or reply with your own thoughts in audio or text format in a part of the web under your control!

Show notes

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Image cropped and rotated from an original by Tim Gouw

Most human beings have an almost infinite capacity for taking things for granted

So said Aldous Huxley. Recently, I discovered a episode of the podcast The Science of Success in which Dan Carlin was interviewed. Now Dan is the host of one of my favourite podcasts, Hardcore History as well as one he's recently discontinued called Common Sense.

The reason the latter is on 'indefinite hiatus' was discussed on The Science of Success podcast. Dan feels that, after 30 years as a journalist, if he can't get a grip on the current information landscape, then who can? It's shaken him up a little.

One of the quotations he just gently lobbed into the conversation was from John Stuart Mill, who at one time or another was accused by someone of being 'inconsistent' in his views. Mill replied:

When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?

John Stuart Mill

Now whether or not Mill said those exact words, the sentiment nevertheless stands. I reckon human beings have always made up their minds first and then chosen 'facts' to support their opinions. These days, I just think that it's easier than ever to find 'news' outlets and people sharing social media posts to support your worldview. It's as simple as that.

Last week I watched a stand-up comedy routine by Kevin Bridges on BBC iPlayer as part of his 2018 tour. As a Glaswegian, he made the (hilarious) analogy of social media as being like going into a pub.

(As an aside, this is interesting, as a decade ago people would often use the analogy of using social media as being like going to an café. The idea was that you could overhear, and perhaps join in with, interesting conversations that you hear. No-one uses that analogy any more.)

Bridges pointed out that if you entered a pub, sat down for a quiet pint, and the person next to you was trying to flog you Herbalife products, constantly talking about how #blessed they felt, or talking ambiguously for the sake of attention, you'd probably find another pub.

He was doing it for laughs, but I think he was also making a serious point. Online, we tolerate people ranting on and generally being obnoxious in ways we would never do offline.

The underlying problem of course is that any platform that takes some segment of the real world and brings it into software will also bring in all that segment's problems. Amazon took products and so it has to deal with bad and fake products (whereas one might say that Facebook took people, and so has bad and fake people).

Benedict Evans

I met Clay Shirky at an event last month, which kind of blew my mind given that it was me speaking at it rather than him. After introducing myself, we spoke for a few minutes about everything from his choice of laptop to what he's been working on recently. Curiously, he's not writing a book at the moment. After a couple of very well-received books (Here Comes Everybody and Cognitive Surplus) Shirky has actually only published a slightly obscure book about Chinese smartphone manufacturing since 2010.

While I didn't have time to dig into things there and then, and it would been a bit presumptuous of me to do so, it feels to me like Shirky may have 'walked back' some of his pre-2010 thoughts. This doesn't surprise me at all, given that many of the rest of us have, too. For example, in 2014 he published a Medium article explaining why he banned his students from using laptops in lectures. Such blog posts and news articles are common these days, but it felt like was one of the first.

The last decade from 2010 to 2019, which Audrey Watters has done a great job of eviscerating, was, shall we say, somewhat problematic. The good news is that we connected 4.5 billion people to the internet. The bad news is that we didn't really harness that for much good. So we went from people sharing pictures of cats, to people sharing pictures of cats and destroying western democracy.

Other than the 'bad and fake people' problem cited by Ben Evans above, another big problem was the rise of surveillance capitalism. In a similar way to climate change, this has been repackaged as a series of individual failures on the part of end users. But, as Lindsey Barrett explains for Fast Company, it's not really our fault at all:

In some ways, the tendency to blame individuals simply reflects the mistakes of our existing privacy laws, which are built on a vision of privacy choices that generally considers the use of technology to be a purely rational decision, unconstrained by practical limitations such as the circumstances of the user or human fallibility. These laws are guided by the idea that providing people with information about data collection practices in a boilerplate policy statement is a sufficient safeguard. If people don’t like the practices described, they don’t have to use the service.

Lindsey Barrett

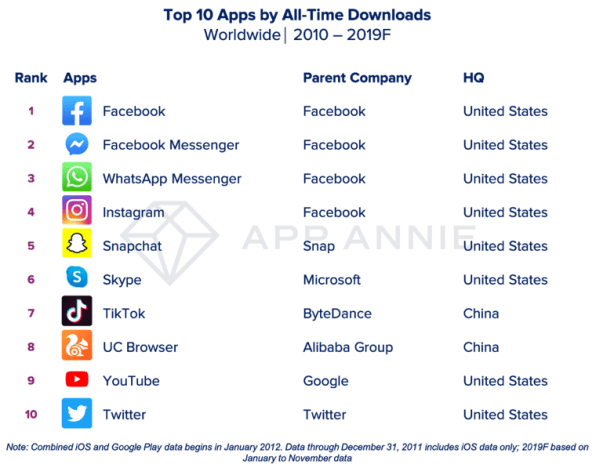

The problem is that we have monopolistic practices in the digital world. Fast Company also reports the four most downloaded apps of the 2010s were all owned by Facebook:

I don't actually think people really understand that their data from WhatsApp and Instagram is being hoovered up by Facebook. I don't then think they understand what Facebook then do with that data. I tried to lift the veil on this a little bit at the event where I met Clay Shirky. I know at least one person who immediately deleted their Facebook account as a result of it. But I suspect everyone else will just keep on keeping on. And yes, I have been banging my drum about this for quite a while now. I'll continue to do so.

The truth is, and this is something I'll be focusing on in upcoming workshops I'm running on digital literacies, that to be an 'informed citizen' these days means reading things like the EFF's report into the current state of corporate surveillance. It means deleting accounts as a result. It means slowing down, taking time, and reading stuff before sharing it on platforms that you know care for the many, not the few. It means actually caring about this stuff.

All of this might just look and feel like a series of preferences. I prefer decentralised social networks and you prefer Facebook. Or I like to use Signal and you like WhatsApp. But it's more than that. It's a whole lot more than that. Democracy as we know it is at stake here.

As Prof. Scott Galloway has discussed from an American point of view, we're living in times of increasing inequality. The tools we're using exacerbate that inequality. All of a sudden you have to be amazing at your job to even be able to have a decent quality of life:

The biggest losers of the decade are the unremarkables. Our society used to give remarkable opportunities to unremarkable kids and young adults. Some of the crowding out of unremarkable white males, including myself, is a good thing. More women are going to college, and remarkable kids from low-income neighborhoods get opportunities. But a middle-class kid who doesn’t learn to code Python or speak Mandarin can soon find she is not “tracking” and can’t catch up.

Prof. Scott Galloway

I shared an article last Friday, about how you shouldn't have to be good at your job. The whole point of society is that we look after one another, not compete with one another to see which of us can 'extract the most value' and pile up more money than he or she can ever hope to spend. Yes, it would be nice if everyone was awesome at all they did, but the optimisation of everything isn't the point of human existence.

So once we come down the stack from social networks, to surveillance capitalism, to economic and markets eating the world we find the real problem behind all of this: decision-making. We've sacrificed stability for speed, and seem to be increasingly happy with dictator-like behaviour in both our public institutions and corporate lives.

Dictatorships can be more efficient than democracies because they don’t have to get many people on board to make a decision. Democracies, by contrast, are more robust, but at the cost of efficiency.

Taylor Pearson

A selectorate, according to Pearson, "represents the number of people who have influence in a government, and thus the degree to which power is distributed". Aside from the fact that dictatorships tend to be corrupt and oppressive, they're just not a good idea in terms of decision-making:

Said another way, much of what appears efficient in the short term may not be efficient but hiding risk somewhere, creating the potential for a blow-up. A large selectorate tends to appear to be working less efficiently in the short term, but can be more robust in the long term, making it more efficient in the long term as well. It is a story of the Tortoise and the Hare: slow and steady may lose the first leg, but win the race.

Taylor Pearson

I don't think we should be optimising human beings for their role in markets. I think we should be optimising markets (if in fact we need them) for their role in human flourishing. The best way of doing that is to ensure that we distribute power and decision-making well.

So it might seem that my continual ragging on Facebook (in particular) is a small thing in the bigger picture. But it's actually part of the whole deal. When we have super-powerful individuals whose companies have the ability to surveil us at will; who then share that data to corrupt regimes; who in turn reinforce the worst parts of the status quo; then I think we have a problem.

This year I've made a vow to be more radical. To speak my mind even more, and truth to power, especially when it's inconvenient. I hope you'll join me ✊

I am not fond of expecting catastrophes, but there are cracks in the universe

So said Sydney Smith. Let's talk about surveillance. Let's talk about surveillance capitalism and surveillance humanitarianism. But first, let's talk about machine learning and algorithms; in other words, let's talk about what happens after all of that data is collected.

Writing in The Guardian, Sarah Marsh investigates local councils using "automated guidance systems" in an attempt to save money.

The systems are being deployed to provide automated guidance on benefit claims, prevent child abuse and allocate school places. But concerns have been raised about privacy and data security, the ability of council officials to understand how some of the systems work, and the difficulty for citizens in challenging automated decisions.

Sarah Marsh

The trouble is, they're not particularly effective:

It has emerged North Tyneside council has dropped TransUnion, whose system it used to check housing and council tax benefit claims. Welfare payments to an unknown number of people were wrongly delayed when the computer’s “predictive analytics” erroneously identified low-risk claims as high risk

Meanwhile, Hackney council in east London has dropped Xantura, another company, from a project to predict child abuse and intervene before it happens, saying it did not deliver the expected benefits. And Sunderland city council has not renewed a £4.5m data analytics contract for an “intelligence hub” provided by Palantir.

Sarah Marsh

When I was at Mozilla there were a number of colleagues there who had worked on the OFA (Obama For America) campaign. I remember one of them, a DevOps guy, expressing his concern that the infrastructure being built was all well and good when there's someone 'friendly' in the White House, but what comes next.

Well, we now know what comes next, on both sides of the Atlantic, and we can't put that genie back in its bottle. Swingeing cuts by successive Conservative governments over here, coupled with the Brexit time-and-money pit means that there's no attention or cash left.

If we stop and think about things for a second, we probably wouldn't don't want to live in a world where machines make decisions for us, based on algorithms devised by nerds. As Rose Eveleth discusses in a scathing article for Vox, this stuff isn't 'inevitable' — nor does it constitute a process of 'natural selection':

Often consumers don’t have much power of selection at all. Those who run small businesses find it nearly impossible to walk away from Facebook, Instagram, Yelp, Etsy, even Amazon. Employers often mandate that their workers use certain apps or systems like Zoom, Slack, and Google Docs. “It is only the hyper-privileged who are now saying, ‘I’m not going to give my kids this,’ or, ‘I’m not on social media,’” says Rumman Chowdhury, a data scientist at Accenture. “You actually have to be so comfortable in your privilege that you can opt out of things.”

And so we’re left with a tech world claiming to be driven by our desires when those decisions aren’t ones that most consumers feel good about. There’s a growing chasm between how everyday users feel about the technology around them and how companies decide what to make. And yet, these companies say they have our best interests in mind. We can’t go back, they say. We can’t stop the “natural evolution of technology.” But the “natural evolution of technology” was never a thing to begin with, and it’s time to question what “progress” actually means.

Rose Eveleth

I suppose the thing that concerns me the most is people in dire need being subject to impersonal technology for vital and life-saving aid.

For example, Mark Latonero, writing in The New York Times, talks about the growing dangers around what he calls 'surveillance humanitarianism':

By surveillance humanitarianism, I mean the enormous data collection systems deployed by aid organizations that inadvertently increase the vulnerability of people in urgent need.

Despite the best intentions, the decision to deploy technology like biometrics is built on a number of unproven assumptions, such as, technology solutions can fix deeply embedded political problems. And that auditing for fraud requires entire populations to be tracked using their personal data. And that experimental technologies will work as planned in a chaotic conflict setting. And last, that the ethics of consent don’t apply for people who are starving.

Mark Latonero

It's easy to think that this is an emergency, so we should just do whatever is necessary. But Latonero explains the risks, arguing that the risk is shifted to a later time:

If an individual or group’s data is compromised or leaked to a warring faction, it could result in violent retribution for those perceived to be on the wrong side of the conflict. When I spoke with officials providing medical aid to Syrian refugees in Greece, they were so concerned that the Syrian military might hack into their database that they simply treated patients without collecting any personal data. The fact that the Houthis are vying for access to civilian data only elevates the risk of collecting and storing biometrics in the first place.

Mark Latonero

There was a rather startling article in last weekend's newspaper, which I've found online. Hannah Devlin, again writing in The Guardian (which is a good source of information for those concerned with surveillance) writes about a perfect storm of social media and improved processing speeds:

[I]n the past three years, the performance of facial recognition has stepped up dramatically. Independent tests by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (Nist) found the failure rate for finding a target picture in a database of 12m faces had dropped from 5% in 2010 to 0.1% this year.

The rapid acceleration is thanks, in part, to the goldmine of face images that have been uploaded to Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and captioned news articles in the past decade. At one time, scientists would create bespoke databases by laboriously photographing hundreds of volunteers at different angles, in different lighting conditions. By 2016, Microsoft had published a dataset, MS Celeb, with 10m face images of 100,000 people harvested from search engines – they included celebrities, broadcasters, business people and anyone with multiple tagged pictures that had been uploaded under a Creative Commons licence, allowing them to be used for research. The dataset was quietly deleted in June, after it emerged that it may have aided the development of software used by the Chinese state to control its Uighur population.

In parallel, hardware companies have developed a new generation of powerful processing chips, called Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), uniquely adapted to crunch through a colossal number of calculations every second. The combination of big data and GPUs paved the way for an entirely new approach to facial recognition, called deep learning, which is powering a wider AI revolution.

Hannah Devlin

Those of you who have read this far and are expecting some big reveal are going to be disappointed. I don't have any 'answers' to these problems. I guess I've been guilty, like many of us have, of the kind of 'privacy nihilism' mentioned by Ian Bogost in The Atlantic:

Online services are only accelerating the reach and impact of data-intelligence practices that stretch back decades. They have collected your personal data, with and without your permission, from employers, public records, purchases, banking activity, educational history, and hundreds more sources. They have connected it, recombined it, bought it, and sold it. Processed foods look wholesome compared to your processed data, scattered to the winds of a thousand databases. Everything you have done has been recorded, munged, and spat back at you to benefit sellers, advertisers, and the brokers who service them. It has been for a long time, and it’s not going to stop. The age of privacy nihilism is here, and it’s time to face the dark hollow of its pervasive void.

Ian Bogost

The only forces that we have to stop this are collective action, and governmental action. My concern is that we don't have the digital savvy to do the former, and there's definitely the lack of will in respect of the latter. Troubling times.

Friday frustrations

I couldn't help but notice these things this week:

Image via @EffinBirds

Friday feeds

These things caught my eye this week:

Header image via Dilbert

Exit option democracy

This week saw the launch of a new book by Shoshana Zuboff entitled The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. It was featured in two of my favourite newspapers, The Observer and the The New York Times, and is the kind of book I would have lapped up this time last year.

In 2019, though, I’m being a bit more pragmatic, taking heed of Stoic advice to focus on the things that you can change. Chiefly, that’s your own perceptions about the world. I can’t change the fact that, despite the Snowden revelations and everything that has come afterwards, most people don’t care one bit that they’re trading privacy for convenience..

That puts those who care about privacy in a bit of a predicament. You can use the most privacy-respecting email service in the world, but as soon as you communicate with someone using Gmail, then Google has got the entire conversation. Chances are, the organisation you work for has ‘gone Google’ too.

Then there’s Facebook shadow profiles. You don’t even have to have an account on that platform for the company behind it to know all about you. Same goes with companies knowing who’s in your friendship group if your friends upload their contacts to WhatsApp. It makes no difference if you use ridiculous third-party gadgets or not.

In short, if you want to live in modern society, your privacy depends on your family and friends. Of course you have the option to choose not to participate in certain platforms (I don’t use Facebook products) but that comes at a significant cost. It’s the digital equivalent of Thoreau taking himself off to Walden pond.

In a post from last month that I stumbled across this weekend, Nate Matias reflects on a talk he attended by Janet Vertesi at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology Policy. Vertesi, says Matias, tried four different ways of opting out of technology companies gathering data on her:

The basic assumption of markets is that people have choices. This idea that “you can just vote with your feet” is called an “exit option democracy” in organizational sociology (Weeks, 2004). Opt-out democracy is not really much of a democracy, says Janet. She should know–she’s been opting out of tech products for years.The option Vertesi advocates for going Google-free is a pain in the backside. I know, because I've tried it:

To prevent Google from accessing her data, Janet practices “data balkanization,” spreading her traces across multiple systems. She’s used DuckDuckGo, sandstorm.io, ResilioSync, and youtube-dl to access key services. She’s used other services occasionally and non-exclusively, and varied it with open source alternatives like etherpad and open street map. It’s also important to pay attention to who is talking to whom and sharing data with whom. Data balkanization relies on knowing what companies hate each other and who’s about to get in bed with whom.The time I've spent doing these things was time I was not being productive, nor was it time I was spending with my wife and kids. It's easy to roll your eyes at people "trading privacy for convenience" but it all adds up.

Talking of family, straying too far from societal norms has, for better or worse, negative consequences. Just as Linux users were targeted for surveillance, so Vertisi and her husband were suspected of fraud for browsing the web using Tor and using cash for transactions:

Trying to de-link your identity from data storage has consequences. For example, when Janet and her husband tried to use cash for their purchases, they faced risks of being reported to the authorities for fraud, even though their actions were legal.And then, of course, there's the tinfoil hat options:

...Janet used parts from electronics kits to make her own 2g phone. After making the phone Janet quickly realized even a privacy-protecting phone can’t connect to the network without identifying the user to companies through the network itself.I'm rolling my eyes at this point. The farthest I've gone down this route is use the now-defunct Firefox OS and LineageOS for microG. Although both had their upsides, they were too annoying to use for extended periods of time.

Finally, Vertesi goes down the route of trying to own all your own data. I’ll just point out that there’s a reason those of us who had huge CD and MP3 collections switched to Spotify. Looking after any collection takes time and effort. It’s also a lot more cost effective for someone like me to ‘rent’ my music instead of own it. The same goes for Netflix.

What I do accept, though, is that Vertesi’s findings show that ‘exit democracy’ isn’t really an option here, so the world of technology isn’t really democratic. My takeaway from all this, and the reason for my pragmatic approach this year, is that it’s up to governments to do something about all this.

Western society teaches us that empowered individuals can change the world. But if you take a closer look, whether it’s surveillance capitalism or climate change, it’s legislation that’s going to make the biggest difference here. Just look at the shift that took place because of GDPR.

So whether or not I read Zuboff’s new book, I’m going to continue my pragmatic approach this year. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to mute the microphone on the smart speakers in our house when they’re not being used, block trackers on my Android smartphone, and continue my monthly donations to work of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Open Rights Group.

Source: J. Nathan Matias