- Celebrate your wins

- Address your losses or weaknesses

- Note your "coulda, woulda, shoulda" tasks

- Create goals for next week

- Summarise it all in one sentence

- Trying (Snakes and Ladders) — "I realized that one of the reasons I like doing the newsletter so much is that I have (quite unconsciously) understood it as a place not to do analysis or critique but to share things that give me delight."

- 43 — All in & with the flow (Buster Benson) — "It’s tempting to always rationalize why our current position is optimal, but as I get older it’s a lot easier to see how things move in cycles, and the cycles themselves are what we should pay attention to more than where we happen to be in them at the moment.

- Four Ways to Figure Out What You Really Want to Do with Your Life (Lifehacker) — "In the end, figuring out your passion, your career path, your life purpose—whatever you want to call it—isn’t an easy process and no magic bullet exists for doing it."

'Restorying' your life as a hero's journey

There are some people, perhaps most people, who do not expect setbacks and problems in life. They seem to think that it should all be smooth sailing, and that anything that interferes with this unarticulated plan is somehow annoying or unfair.

Perhaps because I spent my teenage years reading philosophy (which I studied at university) and then my adult life reading Stoic philosophers such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, this isn’t my view. Instead, I’m well aware that everyone has to deal with setbacks and, in fact, they make you stronger and more focused.

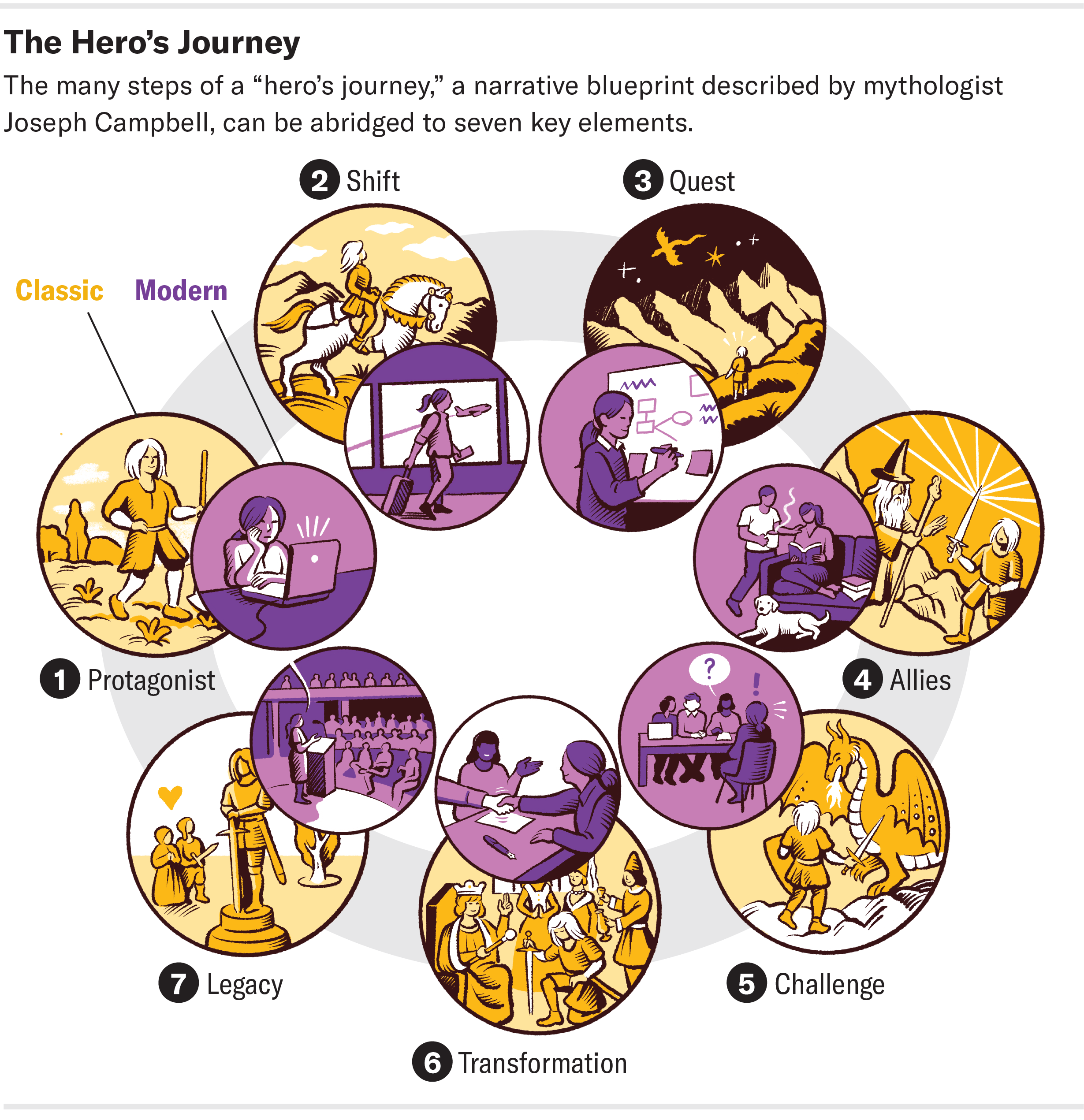

This article discusses the results of research based on interventions taking as its basis The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell. He noticed that cultures around the world had foundational stories which were based on a similar structure. The researchers took this approach, updated it for modern life, and used the structure as an intervention to help individuals to tell better stories about their lives.

What do Beowulf, Batman and Barbie all have in common? Ancient legends, comic book sagas and blockbuster movies alike share a storytelling blueprint called “the hero’s journey.” This timeless narrative structure, first described by mythologist Joseph Campbell in 1949, describes ancient epics, such as the Odyssey and the Epic of Gilgamesh, and modern favorites, including the Harry Potter, Star Wars and Lord of the Rings series. Many hero’s journey stories have become cultural touchstones that influence how people think about their world and themselves.Source: To Lead a Meaningful Life, Become Your Own Hero | Scientific AmericanOur research reveals that the hero’s journey is not just for legends and superheroes. In a recent study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, we show that people who frame their own life as a hero’s journey find more meaning in it. This insight led us to develop a “restorying” intervention to enrich individuals’ sense of meaning and well-being. When people start to see their own lives as heroic quests, we discovered, they also report less depression and can cope better with life’s challenges.

[…]

To explore the connection between people’s life stories and the hero’s journey, we first had to simplify the storytelling arc from Campbell’s original formulation, which featured 17 steps. Some of the steps in the original set were very specific, such as undertaking a “magic flight” after completing a quest. Think of Dorothy, in the novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, being carried by flying monkeys to the Emerald City after vanquishing the Wicked Witch of the West. Others are out of touch with contemporary culture, such as encountering “women as temptresses.” We abridged and condensed the 17 steps into seven elements that can be found both in legends and everyday life: a lead protagonist, a shift of circumstances, a quest, a challenge, allies, a personal transformation and a resulting legacy.

For example, in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo (the protagonist) leaves the Shire (a shift) to destroy the Ring (a quest). Sam and Gandalf (his allies) help him face Sauron’s forces (a challenge). He discovers unexpected inner strength (a transformation) and then returns home to help the friends he left behind (a legacy). In a parallel way in everyday life, a young woman (the protagonist) might move to Los Angeles (a shift), develop an idea for a new business (a quest), get support from her family and new friends (her allies), overcome self-doubt after initial failure (a challenge), grow into a confident and successful leader (a transformation) and then help her community (a legacy).

[…]

Anyone can frame their life as a hero’s journey—and we suspect that people can also benefit from taking small steps toward a more heroic life. You can see yourself as a heroic protagonist, for example, by identifying your values and keeping them top of mind in daily life. You can lean into friendships and new experiences. You can set goals much like those of classic quests to stay motivated—and challenge yourself to improve your skills. You can also take stock of lessons learned and ways that you might leave a positive legacy for your community or loved ones.

Even those of a harsh and unyielding nature will endure gentle treatment: no creature is fierce and frightening if it is stroked

🌼 Digital gardens let you cultivate your own little bit of the internet

⛏️ Dorset mega henge may be ‘last hurrah’ of stone-age builders

📺 Culture to cheer you up during the second lockdown: part one

Quotation-as-title by Seneca. Image from top-linked post.

If you have been put in your place long enough, you begin to act like the place

📉 Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit

💪 How to walk upright and stop living in a cave

🤔 It’s Not About Intention, It’s About Action

💭 Are we losing our ability to remember?

🇺🇸 How The Presidential Candidates Spy On Their Supporters

Quotation-as-title by Randall Jarrell. Image from top-linked post.

Thus each man ever flees himself

There are some days during this current pandemic when, coccooned in my little bubble, I can forget for a few hours that the world has changed. Conversely, I encounter other days when my baseline existential angst spikes to a level just below "rocking backwards-and-forwards in the corner of the room".

There are a range of ways for obtaining help in such situations, including professional (therapy!), spiritual (religion!) and medical (drugs!) However, while I've dabbled with all three, perhaps my greatest solace comes from bunch of balding white dudes who lived a couple of thousand years ago.

Yes, I'm talking about the Stoics. Having re-read the Seneca's On the Tranquility of the Mind this week, I thought there were whole sections worth sharing for anyone in a similar predicament to me.

In this dialogue, Serenus explains to Seneca his problem. The details may have changed over the years (no slaves, and we tend not to be so envious about other people's crockery) but the gist is, at least for me, immediately recognisable:

The nature of this mental weakness which hovers between two alternatives, inclining strongly neither to the right nor to the wrong, I can better show you one part at a time than all at once; I will tell you my experience, you will find a name for my sickness. I am completely devoted, I admit, to frugality: I do not like a couch made up for show, or clothing produced from a chest or pressed by weights and a thousand mangles to make it shiny, but rather something homely and inexpensive that has not been kept specially or needs to be put on with anxious care; I like food that a household of slaves has not pr pared, watching it with envy, that has not been ordered many days in advance or served up by many hands, but is easy to fetch and in ample supply; it has nothing outlandish or expensive about it, and will be readily available everywhere, it will not put a strain on one’s purse or body, or return by the way it entered; I like for my servant a young house-bred slave without training or polish, for silverware my country-bred father’s heavy plate that bears no maker’s stamp, and for a table one that is not remarkable for the variety of its markings or known to Rome for having passed through the hands of many stylish owners, but one that is there to be used, that makes no guest stare at it in endless pleasure or burning envy. Then, after finding perfect satisfaction in all such things, I find my mind is dazzled by the splendour of some training-school for pages, by the sight of slaves decked out in gold and more scrupulously dressed than bearers in a procession, and a whole troop of brilliant attendants; by the sight of a house where even the floor one treads is precious and riches are strewn in every corner, where the roofs themselves shine out, and the citizen body waits in attendance and dutifully accompanies an inheritance whose days are numbered; need I mention the waters, transparent to the bottom and flowing round the guests even as they dine, or the banquets that in no way disgrace their setting? Emerging from a long time of dedication to thrift, luxury has enveloped me in the riches of its splendour, filling my ears with all its sounds: my vision falters a little, for it is easier for me to raise my mind to it than my eyes; and so I come back, not a worse man, but a sadder one, I no longer walk with head so high among those worthless possessions of mine, and I feel the sharpness of a secret pain as the doubt arises whether that life is not the better one. None of these things alters me, but none fails to unsettle me.

'Serenus' (in Seneca's 'On The Tranquility of the Mind')

As a result, Serenus asks Seneca for help, as he feels stuck between two stools: asceticism and luxury:

I ask you, therefore, if you possess any cure by which you can check this fluctuation of mine, to consider me worthy of being indebted to you for tranquillity. I am aware that these mental disturbances I suffer from are not dangerous and bring no threat of a storm; to express to you in a true analogy the source of my complaint, it is not a storm I labour under but seasickness: relieve me, then, of this malady, whatever it be, and hurry to aid one who struggles with land in his sight.

'Serenus' (in seneca's 'On The Tranquility of the Mind')

For me, Serenus' description of his 'mental disturbances' as being like seasickness really resonate with me. As a friend said earlier this week, we're both a little tired of the "constant up and down".

Seneca restates Serenus' problem, first stating what he doesn't require:

Accordingly, you have no need of those harsher measures that we have already passed over, that of sometimes opposing yourself, of sometimes getting angry with yourself, of sometimes fiercely driving yourself on, but rather of the one that comes last, having confidence in yourself and believing that you are on the right path and have not been sidetracked by the footprints crossing over, left by many rushing in different directions, some of them wandering close to the path itself.

seneca, 'On The Tranquility of the Mind'

Another useful metaphor, of being sidetracked by other people's, and perhaps your own, footprints. Instead what Seneca explains that Serenus needs to have "confidence" in himself, and believe that he is "on the right path".

Don't we all need that?

Seneca continues by saying that everyone is in the same boat, which might as well be named The Human Condition. What he diagnoses as the nub of the problem, which is think is particularly insightful, is our attempts to keep changing things. Ultimately, this simply means we live in a constant state of suspense and dissatisfaction.

Everyone is in the same predicament, both those who are tormented by inconstancy and boredom and an unending change of purpose, constantly taking more pleasure in what they have just abandoned, and those who idle away their time, yawning. Add to them those who twist and turn like insomniacs, trying all manner of positions until in their weariness they find repose: by altering the condition of their life repeatedly, they end up finally in the state that they are caught, not by dislike of change, but by old age that is reluctant to embrace anything new. Add also those who through the fault, not of determination but of idleness, are too constant in their ways, and live their lives not as they wish, but as they began. The sickness has countless characteristics but only one effect, dissatisfaction with oneself. This arises from a lack of mental balance and desires that are nervous or unfulfilled, when men’s daring or attainment falls short of their desires and they depend entirely on hope; such are always lacking in stability and changeable, the inevitable consequence of living in a state of suspense.

seneca, 'On The Tranquility of the Mind'

Next, Seneca seemingly reaches through the ages to drive his point home with sentences which, despite being aimed at his interlocutor, seem targeted at me.

All these feelings are aggravated when disgust at the effort they have spent on becoming unsuccessful drives men to leisure, to solitary studies, which are unendurable for a mind intent on a public career, eager for employment, and by nature restless, since without doubt it possesses few enough resources for consolation; for this reason, once it has been deprived of those delights that business itself affords to active participants, the mind does not tolerate home, solitude, or the walls of a room, and does not enjoy seeing that it has been left to itself. This is the source of that boredom and dissatisfaction, of the wavering of a mind that finds no rest anywhere, and the sad and spiritless endurance of one’s leisure; and particularly when one is ashamed to confess the reasons for these feelings, and diffidence drives its torments inwards, the desires, confined in a narrow space from which there is no escape, choke one-another; hence come grief and melancholy and the thousand fluctuations of an uncertain mind, held in suspense by early hopes and then reduced to sadness once they fail to materialize; this causes that feeling which makes men loathe their own leisure and complain that they themselves have nothing to keep them occupied, and also the bitterest feelings of jealousy of other men’s successes.

Seneca, 'On The Tranquility of the Mind'

Seneca continues to give Serenus more advice in the dialogue, but, every time I read these opening few pages, I feel like he has diagnosed not only my condition, and that of all humankind.

While some people are always on the lookout for the new and the novel, I'm realising that the best way to spend the second half of my life might well be to spend a good amount of time wringing out as much value from things I've already discovered.

The quotations in this post are from the Oxford World's Classics version of Seneca's Dialogues and Essays. If you can't find it in your local library, try here.

If you're new to the Stoics, may I suggest starting with The Enchiridion by Epictetus? I'd follow that with Marcus Aurelius' Meditations (buy a decent quality dead-tree version; you'll thank me in years to come) and then dip into Seneca's somewhat voluminous works.

Header image by Simon Migaj. Quotation-as-title from Lucretius, who Seneca quotes in 'On the Tranquility of the Mind'.

To refrain from imitation is the best revenge

Today's title comes from Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, which regular readers of my writing will know I read on repeat. George Herbert, the English poet, wrote something similar to this in "living well is the best revenge".

But what do these things actually mean in practice?

One of my favourite episodes of Frasier (the only sitcom I've ever really enjoyed) is when Niles has to confront his childhood bully. It leads to this magnificent exchange:

Frasier:

You know the expression, "Living well is the best revenge"?

Niles:

It's a wonderful expression. I just don't know how true it is. You don't see it turning up in a lot of opera plots. "Ludwig, maddened by the poisoning of his entire family, wreaks vengeance on Gunther in the third act by living well."

Frasier:

All right, Niles.

Niles:

"Whereupon Woton, upon discovering his deception, wreaks vengeance on Gunther in the third act again by living even better than the Duke."

Frasier:

Oh, all right!

In other words, it often doesn't feel that 'living well' makes any tangible difference.

But let's step back a moment. What does it mean to 'live well'? Is it the same as refraining from imitating others, or are Marcus Aurelius and George Herbert talking about two entirely different things?

During an email exchange last week, someone mentioned that they weren't sure whether my segues between topics were 'brilliant' or 'tenuous'. Well, dear reader, here's a chance to judge for yourself....

In a recent article for Fast Company, ostensibly about 'personal branding' Trip O'Dell gets awfully deep awfully quickly and starts invoking Aristotle:

Aristotle is the father of Western philosophy because he didn’t focus on likes, engagement, or followers. Aristotle focused on the nature of authenticity; what it means to be real but also persuasive. He broke the requirements for persuasiveness into four simple elements: ethos (reputation/authority), logos (logic), pathos (feeling), and kairos (timing). Those four elements are required to argue persuasively in any context. However, the stakes are higher in business. Confidently communicating who you are, what you stand for, and why you’re great at what you do is not only essential, it’s liberating.

Trip O'Dell

What I particularly like about the article is the re-focusing on 'personal ethos' rather than 'personal brand'. Branding is a form of marketing, of changing the surface appearance of something. It's about morphing a product (in this case, yourself) into something that better fits in with what other people expect.

An ethos runs much deeper. It is, as Aristotle noted, about your reputation or authority, neither of which are manufactured overnight.

The hardest part of establishing a professional ethos is describing it; it takes work, and it isn’t easy. The process requires a level of maturity and self-awareness that can be uncomfortable at times. You’re forced to ask some essential questions and make yourself vulnerable to critique and rejection. That discomfort is the tax that is paid to eliminate self-defeating habits that hold many people back in their professional lives.

Trip O'Dell

This is where that magnificent word 'authenticity' comes in. No-one really knows what it means, but everyone wants to have it. I'd argue that authenticity is a by-product of reputation and authority. Easy to destroy, difficult to build.

Let me set my stall out by saying that I think that Marcus Aurelius ("To refrain from imitation is the best revenge") and George Herbert ("Living well is the best revenge") were actually talking about much the same thing.

I don't know much about George Herbert, but Wikipedia tells me he was an orator as well as a poet, and fluent in Latin and Greek. So I'm surmising that he at least had a passing knowledge of the Stoics. The chances are he was using his poetic flair to make Marcus Aurelius' quotation a little more memorable.

Revenge can be dramatic and explosive. It can be as subtle as tiny daggers. Either way, revenge involves communicating something to another person in such a way that they realise you've got one up on them.

Malice may or may not be involved; it's probably better if it isn't. The pop diva Mariah Carey is the queen of this, claiming that she "doesn't know" people with whom she's allegedly having a feud.

But, back to the dead white dudes. In How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, Donald Robertson explains that the Stoics saw that both way we live and the way we communicate as important.

The Stoics realized that to communicate wisely, we must phrase things appropriately. Indeed, according to Epictetus, the most striking characteristic of Socrates was that he never became irritated during an argument. He was always polite and refrained from speaking harshly even when others insulted him. He patiently endured much abuse and yet was able to put an end to most quarrels in a calm and rational manner.

Donald J. Robertson

In other words, you don't need to imitate other people's anger, irritability, or lack of patience. You can 'live well' by being comfortable in your own skin and demonstrate the calm waters of your soul.

This, of course, is hard work. Nietzsche is famously quoted as saying:

He who fights too long against dragons becomes a dragon himself; and if you gaze too long into the abyss, the abyss will gaze into you.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

Feel free to substitute 'internet trolls' or 'petty-minded neighbours' for 'dragons'. The effect is the same. Marcus Aurelius is reminding us that refraining from imitating their behaviour is the best form of revenge.

Likewise, George Herbert is telling us that 'living well' is (as Trip O'Dell notes in that Fast Company article) about having a 'personal ethos'. It's about knowing who you are and where you're going. And, potentially, acting like Mariah Carey, throwing shade on your enemies by not acknowledging their existence.

Even in their sleep men are at work

For today's title I've used Marcus Aurelius' more concise, if unfortunately gendered, paraphrasing of a slightly longer quotation from Heraclitus. It's particularly relevant to me at the moment, as recently I've been sleepwalking. This isn't a new thing; I've been doing it all my life when something's been bothering me.

When I tell people about this, they imagine something similar to the cartoon above. The reality is somewhat more banal, with me waking up almost as soon as I get out of bed and then getting back into it.

Sometimes I'm not entirely sure what's bothering me. Other times I do, but it's a combintion of things. In an article for Inc. Amy Morin gives some advice, explains there's an important difference between 'ruminating' and 'problem-solving':

If you're behind on your bills, thinking about how to get caught up can be helpful. But imagining yourself homeless or thinking about how unfair it is that you got behind isn't productive.

So ask yourself, "Am I ruminating or problem-solving?"

Amy Morin

If you're dwelling on the problem, you're ruminating. If you're actively looking for solutions, you're problem-solving.

Morin goes on to talk about 'changing the channel' which can be a very difficult thing to do. One thing that helps me is reading the work of Stoic philosophers such as The Enchiridion by Epictetus, which begins with some of the best advice I've ever read:

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.

The things in our control are by nature free, unrestrained, unhindered; but those not in our control are weak, slavish, restrained, belonging to others. Remember, then, that if you suppose that things which are slavish by nature are also free, and that what belongs to others is your own, then you will be hindered. You will lament, you will be disturbed, and you will find fault both with gods and men. But if you suppose that only to be your own which is your own, and what belongs to others such as it really is, then no one will ever compel you or restrain you. Further, you will find fault with no one or accuse no one. You will do nothing against your will. No one will hurt you, you will have no enemies, and you not be harmed.

Aiming therefore at such great things, remember that you must not allow yourself to be carried, even with a slight tendency, towards the attainment of lesser things. Instead, you must entirely quit some things and for the present postpone the rest. But if you would both have these great things, along with power and riches, then you will not gain even the latter, because you aim at the former too: but you will absolutely fail of the former, by which alone happiness and freedom are achieved.

Work, therefore to be able to say to every harsh appearance, "You are but an appearance, and not absolutely the thing you appear to be." And then examine it by those rules which you have, and first, and chiefly, by this: whether it concerns the things which are in our own control, or those which are not; and, if it concerns anything not in our control, be prepared to say that it is nothing to you.

Epictetus

Donald Robertson, founder of Modern Stoicism, is an author and psychotherapist. Robertson was interviewed by Knowledge@Wharton for their podcast, which they've also transcribed. He makes a similar point to Epictetus, based on the writings of Marcus Aurelius:

Ultimately, the only thing that’s really under our control is our own will, our own actions. Things happen to us, but what we can really control is the way that we respond to those things. Stoicism wants us to take also greater responsibility, greater ownership for the things that we can actually do, both in terms of our thoughts and our actions, and respond to the situations that we face.

Donald Robertson

Robertson talks in the interview about how Stoicism has helped him personally:

It’s helped me to cope with a lot of things, even relatively trivial things. The last time I went to the dentist, I’m sure I was using Stoic pain management techniques. It becomes a habitual thing. Coping with some of the stress that therapists have when they’re dealing with clients who sometimes describe very traumatic problems, and the stress of working with other people who have their difficulties and stresses. [I moved] to Canada a few years ago, and that was a big upheaval for me. As for many people, a life-changing event like that can require a lot to deal with. Learning to think about things like a Stoic has helped me to negotiate all of these things in life.

Donald Robertson

Although I haven't done it since August 2010(!) I used to do something which I referred to as "calling myself into the office". The idea was that I'd set myself three to five goals, and then review them at the end of the month. I'd also set myself some new goals.

The value of doing this is that you can see that you're making progress. It's something that I should definitely start doing again. I was reminded of this approach after reading an article at Career Contessa about weekly self-evaluations. The suggested steps are:

While Career Contessa suggests this will all take only five minutes, I think that if you did it properly it might take more like 20 minutes to half an hour. Whether you do it weekly or monthly probably depends on the size of the goals you're trying to achieve. Either way, it's a valuable exercise.

We all need to cut ourselves some slack, to go easy on ourselves. The chances are that the thing we're worrying about isn't such a big deal in the scheme of things, and the world won't end if we don't get that thing done right now. Perhaps regular self-examination, whether through Stoicism or weekly/monthly reviews, can help more of us with that?

Also check out:

You cant escape your problems through travel

I work from home, but travel quite a bit for the kind of work I do. I’ve noticed how, after three weeks of being based at home, I get restless. The four walls of my home office get a little bit stifling, even if I do augment them with the occasional working visit to the local coffee shop.

Work travel is, of course, different to holiday/vacation. However, as I write this from Montana, USA, I’m reminded how easy it is to slip into the mindset of how travel or money or a relationship can solve your problems in life.

This heavily-illustrated article is a good reminder that your need to sort out your life is independent from external things, including travel.

The reason I read Stoic philosophy every day is that it can give you a perspective of happiness that is independent of location, financial circumstances, or relationship status.Travel is the answer much of us look to when we feel the automation of life. The routine of waking up, getting ready, going to work, eating the same lunch, sitting in meetings, getting off work, going home, eating dinner, relaxing, going to sleep, and then doing it all over again can feel like a never-ending road that is housed within the confines of a mundane box.

Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher, was lame and, it is thought, an ex-slave. We only know his teachings from the notes that his students made, but his message is pretty clear. Here's the very first section of the Enchiridion. It might not change your life the first time you read it, but try reading it every day for a month:Since much of what we desire lives on the outside (i.e. in the future), we make it the mission of our Box of Daily Experience to make contact with the outer world as much as possible. This touch represents the achievement of our goals and validates our aspirations. We hope that this brief contact will change the architecture of our box, but ultimately, the result is fleeting.

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.The only thing that can make you happy, calm, and contented is controlling your reactions to external prompts. That’s it. But it takes a lifetime to figure out.The things in our control are by nature free, unrestrained, unhindered; but those not in our control are weak, slavish, restrained, belonging to others. Remember, then, that if you suppose that things which are slavish by nature are also free, and that what belongs to others is your own, then you will be hindered. You will lament, you will be disturbed, and you will find fault both with gods and men. But if you suppose that only to be your own which is your own, and what belongs to others such as it really is, then no one will ever compel you or restrain you. Further, you will find fault with no one or accuse no one. You will do nothing against your will. No one will hurt you, you will have no enemies, and you not be harmed.

Aiming therefore at such great things, remember that you must not allow yourself to be carried, even with a slight tendency, towards the attainment of lesser things. Instead, you must entirely quit some things and for the present postpone the rest. But if you would both have these great things, along with power and riches, then you will not gain even the latter, because you aim at the former too: but you will absolutely fail of the former, by which alone happiness and freedom are achieved.

Work, therefore to be able to say to every harsh appearance, “You are but an appearance, and not absolutely the thing you appear to be.” And then examine it by those rules which you have, and first, and chiefly, by this: whether it concerns the things which are in our own control, or those which are not; and, if it concerns anything not in our control, be prepared to say that it is nothing to you.

Source: More To That

You cant escape your problems through travel

I work from home, but travel quite a bit for the kind of work I do. I’ve noticed how, after three weeks of being based at home, I get restless. The four walls of my home office get a little bit stifling, even if I do augment them with the occasional working visit to the local coffee shop.

Work travel is, of course, different to holiday/vacation. However, as I write this from Montana, USA, I’m reminded how easy it is to slip into the mindset of how travel or money or a relationship can solve your problems in life.

This heavily-illustrated article is a good reminder that your need to sort out your life is independent from external things, including travel.

The reason I read Stoic philosophy every day is that it can give you a perspective of happiness that is independent of location, financial circumstances, or relationship status.Travel is the answer much of us look to when we feel the automation of life. The routine of waking up, getting ready, going to work, eating the same lunch, sitting in meetings, getting off work, going home, eating dinner, relaxing, going to sleep, and then doing it all over again can feel like a never-ending road that is housed within the confines of a mundane box.

Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher, was lame and, it is thought, an ex-slave. We only know his teachings from the notes that his students made, but his message is pretty clear. Here's the very first section of the Enchiridion. It might not change your life the first time you read it, but try reading it every day for a month:Since much of what we desire lives on the outside (i.e. in the future), we make it the mission of our Box of Daily Experience to make contact with the outer world as much as possible. This touch represents the achievement of our goals and validates our aspirations. We hope that this brief contact will change the architecture of our box, but ultimately, the result is fleeting.

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.The only thing that can make you happy, calm, and contented is controlling your reactions to external prompts. That’s it. But it takes a lifetime to figure out.The things in our control are by nature free, unrestrained, unhindered; but those not in our control are weak, slavish, restrained, belonging to others. Remember, then, that if you suppose that things which are slavish by nature are also free, and that what belongs to others is your own, then you will be hindered. You will lament, you will be disturbed, and you will find fault both with gods and men. But if you suppose that only to be your own which is your own, and what belongs to others such as it really is, then no one will ever compel you or restrain you. Further, you will find fault with no one or accuse no one. You will do nothing against your will. No one will hurt you, you will have no enemies, and you not be harmed.

Aiming therefore at such great things, remember that you must not allow yourself to be carried, even with a slight tendency, towards the attainment of lesser things. Instead, you must entirely quit some things and for the present postpone the rest. But if you would both have these great things, along with power and riches, then you will not gain even the latter, because you aim at the former too: but you will absolutely fail of the former, by which alone happiness and freedom are achieved.

Work, therefore to be able to say to every harsh appearance, “You are but an appearance, and not absolutely the thing you appear to be.” And then examine it by those rules which you have, and first, and chiefly, by this: whether it concerns the things which are in our own control, or those which are not; and, if it concerns anything not in our control, be prepared to say that it is nothing to you.

Source: More To That

The role of Lady Luck

This post on Of Dollars and Data is a bit rambling, at least from my perspective, but I did like this paragraph:

I think this chimes well with Stoic philosophy: focus on the things within you control. There are going to be times in all of our lives when bad things happen. Conversely, there are going to be times when good things happen. We can't control anything apart from our reactions to these things.Think about the story you tell yourself about yourself. In all the lives you could be living, in all of the worlds you could simulate, how much did luck play a role in this one? Have you gotten more than your fair share? Have you had to deal with more struggles than most? I ask you this question because accepting luck as a primary determinant in your life is one of the most freeing ways to view the world. Why? Because when you realize the magnitude of happenstance and serendipity in your life, you can stop judging yourself on your outcomes and start focusing on your efforts. It’s the only thing you can control.

Source: Of Dollars and Data

The role of Lady Luck

This post on Of Dollars and Data is a bit rambling, at least from my perspective, but I did like this paragraph:

I think this chimes well with Stoic philosophy: focus on the things within you control. There are going to be times in all of our lives when bad things happen. Conversely, there are going to be times when good things happen. We can't control anything apart from our reactions to these things.Think about the story you tell yourself about yourself. In all the lives you could be living, in all of the worlds you could simulate, how much did luck play a role in this one? Have you gotten more than your fair share? Have you had to deal with more struggles than most? I ask you this question because accepting luck as a primary determinant in your life is one of the most freeing ways to view the world. Why? Because when you realize the magnitude of happenstance and serendipity in your life, you can stop judging yourself on your outcomes and start focusing on your efforts. It’s the only thing you can control.

Source: Of Dollars and Data

On struggle

The popular view of life seems to be that mishaps, hardship, and struggle are all things that most people can avoid. If we stop to think about that for a second, that’s obviously untrue; in fact, the opposite is the case.

This article in Lifehacker quotes Seneca, one of my favourite Stoic philosophers:

As part of my daily reading, I meditate on other tenets of Stoicism. The opening to Epictetus' Enchiridion tells you pretty much everything you need to know:“Why, then, should we be angry? Why should we lament? We are prepared for our fate: let nature deal as she will with her own bodies; let us be cheerful whatever befalls, and stoutly reflect that it is not anything of our own that perishes. What is the duty of a good man? To submit himself to fate: it is a great consolation. To be swept away together with the entire universe: whatever law is laid upon us that thus we must live and thus we must die, is laid upon the gods.”

Of things some are in our power, and others are not. In our power are opinion, movement toward a thing, desire, aversion (turning from a thing); and in a word, whatever are our own acts: not in our power are the body, property, reputation, offices (magisterial power), and in a word, whatever are not our own acts. And the things in our power are by nature free, not subject to restraint nor hindrance: but the things not in our power are weak, slavish, subject to restraint, in the power of others. Remember then that if you think the things which are by nature slavish to be free, and the things which are in the power of others to be your own, you will be hindered, you will lament, you will be disturbed, you will blame both gods and men: but if you think that only which is your own to be your own, and if you think that what is another’s, as it really is, belongs to another, no man will ever compel you, no man will hinder you, you will never blame any man, you will accuse no man, you will do nothing involuntarily (against your will), no man will harm you, you will have no enemy, for you will not suffer any harm.It's also worth dwelling on this from Marcus Aurelius' Meditations:

Begin each day by telling yourself: Today I shall be meeting with interference, ingratitude, insolence, disloyalty, ill-will, and selfishness – all of them due to the offenders’ ignorance of what is good or evil.Suffering is part of life, and we should embrace it. Control what you can control, and let the rest go.

Source: Lifehacker

What we can learn from Seneca about dying well

As I’ve shared before, next to my bed at home I have a memento mori, an object to remind me before I go to sleep and when I get up that one day I will die. It kind of puts things in perspective.

“Study death always,” Seneca counseled his friend Lucilius, and he took his own advice. From what is likely his earliest work, the Consolation to Marcia (written around AD 40), to the magnum opus of his last years (63–65), the Moral Epistles, Seneca returned again and again to this theme. It crops up in the midst of unrelated discussions, as though never far from his mind; a ringing endorsement of rational suicide, for example, intrudes without warning into advice about keeping one’s temper, in On Anger. Examined together, Seneca’s thoughts organize themselves around a few key themes: the universality of death; its importance as life’s final and most defining rite of passage; its part in purely natural cycles and processes; and its ability to liberate us, by freeing souls from bodies or, in the case of suicide, to give us an escape from pain, from the degradation of enslavement, or from cruel kings and tyrants who might otherwise destroy our moral integrity.Seneca was forced to take his own life by his own pupil, the more-than-a-little-crazy Roman Emperor, Nero. However, his whole life had been a preparation for such an eventuality.

Seneca, like many leading Romans of his day, found that larger moral framework in Stoicism, a Greek school of thought that had been imported to Rome in the preceding century and had begun to flourish there. The Stoics taught their followers to seek an inner kingdom, the kingdom of the mind, where adherence to virtue and contemplation of nature could bring happiness even to an abused slave, an impoverished exile, or a prisoner on the rack. Wealth and position were regarded by the Stoics as adiaphora, “indifferents,” conducing neither to happiness nor to its opposite. Freedom and health were desirable only in that they allowed one to keep one’s thoughts and ethical choices in harmony with Logos, the divine Reason that, in the Stoic view, ruled the cosmos and gave rise to all true happiness. If freedom were destroyed by a tyrant or health were forever compromised, such that the promptings of Reason could no longer be obeyed, then death might be preferable to life, and suicide, or self-euthanasia, might be justified.Given that death is the last taboo in our society, it's an interesting way to live your life. Being ready at any time to die, having lived a life that you're satisfied with, seems like the right approach to me.

“Study death,” “rehearse for death,” “practice death”—this constant refrain in his writings did not, in Seneca’s eyes, spring from a morbid fixation but rather from a recognition of how much was at stake in navigating this essential, and final, rite of passage. As he wrote in On the Shortness of Life, “A whole lifetime is needed to learn how to live, and—perhaps you’ll find this more surprising—a whole lifetime is needed to learn how to die.”Source: Lapham's Quarterly

Money in, blood out

A marvellous post by Ryan Holiday, who is well versed in Stoic philosophy:

Seneca, the Roman statesman and writer, spoke often about wealthy Romans who have spent themselves into debt and the misery and dependence this created for them. Slavery, he said, often lurks beneath marble and gold. Yet, his own life was defined by these exact debts. With his own fortune, he made large loans to a colony of Britain at rates so high it eventually destroyed their economy. And what was the source of this fortune? The Emperor Nero was manipulatively generous with Seneca, bestowing upon him numerous estates and monetary awards in exchange for his advice and service. Seneca probably could have said no, but after he accepted the first one, the hooks were in. As Nero grew increasingly unstable and deranged, Seneca tried to escape into retirement but he couldn’t. He pushed all the wealth into a pile and offered to give it back with no luck.Eventually, death—a forced suicide—was the only option. Money in, blood out.

You need to know what you stand for in life so you can politely decline those things that don’t mesh with your expectations and approach to life. This takes discipline, and discipline takes practice.

Source: Thought Catalog