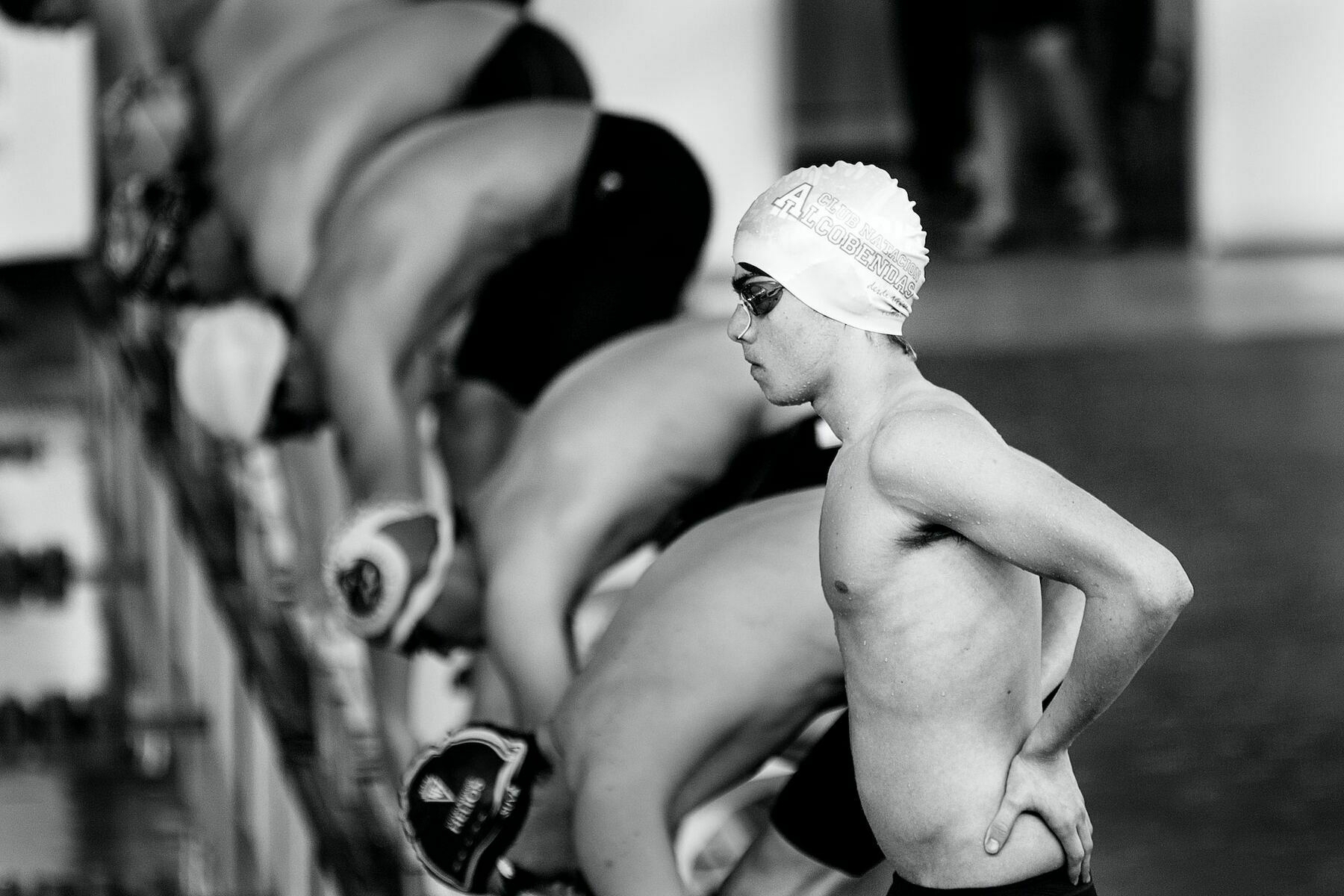

B Lane

There’s a lot going on in this short post. It reminded me of a saying of Steve Jobs: “A players attract A players. B players attract C players.”

Now there’s something in that, in terms of the mentality that people bring to working hard and playing hard. But this post is talking about the way that people treat other people.

I’ve definitely noticed in my life, from my own studies to my kids sports teams, the tyranny of the “not quite top-level” mindset. It’s almost like you have to get over yourself to get to the “top”. What that is and whether it’s worth pursuing is another question entirely.

I noticed that when I swam next to the B lane swimmers, they were not nearly as kind and friendly as the C lane swimmers had been when they were my next-lane neighbours. The A lane swimmers were extremely nice, and were generous with encouragement, praise and tips. This wasn’t a hard and fast rule, but I started to notice a pattern: A, C, and D lane swimmers tended to be nice, friendly, and helpful to pretty much everyone; B lane swimmers tended to be nice to A lane and other B lane swimmers but not so much to C and D.Source: The B Lane Swimmer | Holly WittemanWhen I stopped doing tris and moved back to field sports, I started to notice the same thing. The very top athletes were nice to everyone and so were the middle and bottom of the pack. The not quite top players, though, were less friendly. They played more political games, and acted out their threatened feelings of being not quite good enough by being snobbish to those below them. (In retrospect, I worry I did some of this, too, especially when I was playing on a top team but was not a top player. I definitely felt a need to prove myself.)

I have since noted the same phenomenon in nearly every domain, including academia. The truly great researchers are generous and friendly; so are many of the middle of the roaders. Those who have something to prove, though, and who feel like they aren’t quite managing to do it, show definite aspects of being B lane swimmers.

Image: Quino AI

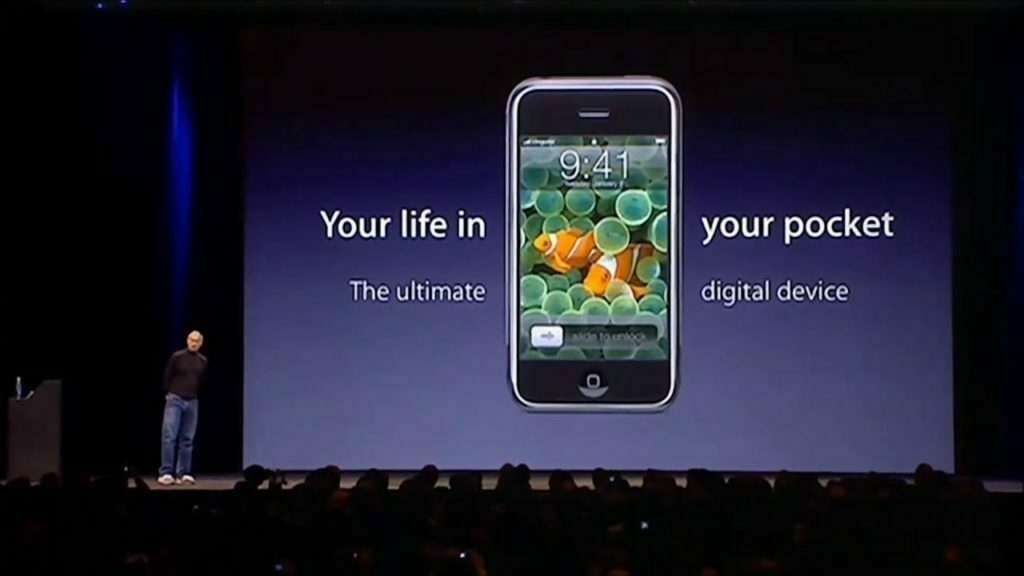

A world without apps?

When Steve Jobs demonstrated the iPhone in 2007, he didn't show off the App Store. That's because it didn't exist.

The full Safari engine is inside of iPhone. And so, you can write amazing Web 2.0 and Ajax apps that look exactly and behave exactly like apps on the iPhone. And these apps can integrate perfectly with iPhone services. They can make a call, they can send an email, they can look up a location on Google Maps.

Steve Jobs

Jobs' vision was for a world where web apps worked as well as native apps. Unfortunately, at the time, web technologies weren't quite ready for his vision, so, almost as a temporary workaround, Apple invented a billion-dollar industry.

Writing in The New York Times, Shira Ovide reflects on the recent controversy around Epic Games and Apple, among other things, and wonders whether we actually need apps?

Apple and Google dictate much of what is allowed on the world’s phones. There are good outcomes from this, including those companies weeding out bad or dangerous apps and giving us one place to find them.

But this comes with unhappy side effects. Apple and Google charge a significant fee on many in-app purchases, and they’ve forced app makers into awkward workarounds. (Ever try to buy a Kindle e-book on an iPhone app? You can’t.) The growing complaints from app makers show that the downsides of app control may be starting to outweigh the benefits.

You know what’s free from Apple and Google’s iron grip? The web. Smartphones could lean on the web instead.

Shira Ovide, Imagine a World Without Apps (The new York Times)

It's almost impossible for a small developer to get discovered in the Apple and Google app stores these days. As VentureBeat put it three years ago, "you have a better chance of making the NBA than making your app viral."

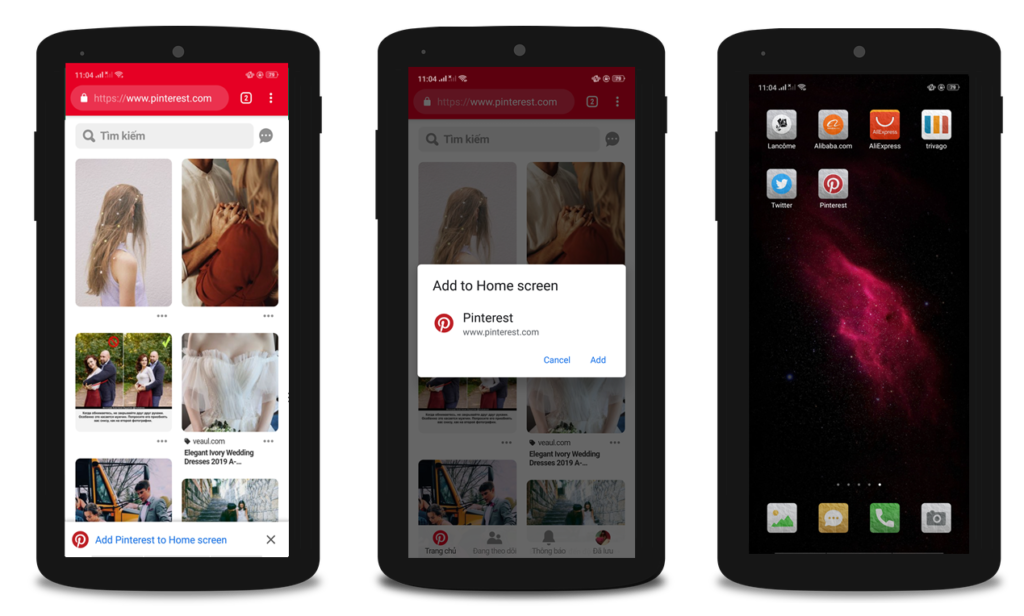

Progressive Web Apps, or PWAs, make an alternative, web-centric world a reality. When Google launched its gaming service, Stadia, on iOS, it used a PWA to bypass the Apple App Store.

Organisations from Twitter and Tinder to the Financial Times have PWAs. Pinterest used it to increase the number of people installing their app by 45%.

This is about imagining an alternate reality where companies don’t need to devote money to creating apps that are tailored to iPhones and Android phones, can’t work on any other devices and obligate app makers to hand over a cut of each sale.

Maybe more smaller digital companies could thrive. Maybe our digital services would be cheaper and better. Maybe we’d have more than two dominant smartphone systems. Or maybe it would be terrible. We don’t know because we’ve mostly lived with unquestioned smartphone app dominance.

Shira Ovide, Imagine a World Without Apps (The new York Times)

Initiatives such as Mozilla's Firefox OS were cursed with being too early to the market. Had they kept going, or if it were launching now, I think we'd see very different adoption rates.

As it is, and as Todd Weaver, CEO of Purism points out, it's going to require a combination of both market dynamics and regulation to fix the current situation. Let's get back to that original vision of the web as the platform for human flourishing.