- Payments: Mastercard, PayPal, PayU (Naspers’ fintech arm), Stripe, Visa

- Technology and marketplaces: Booking Holdings, eBay, Facebook/Calibra, Farfetch, Lyft, MercadoPago, Spotify AB, Uber Technologies, Inc.

- Telecommunications: Iliad, Vodafone Group

Blockchain: Anchorage, Bison Trails, Coinbase, Inc., Xapo Holdings Limited - Venture Capital: Andreessen Horowitz, Breakthrough Initiatives, Ribbit Capital, Thrive Capital, UnionSquare Ventures

- Nonprofit and multilateral organizations, and academic institutions: Creative Destruction Lab, Kiva,Mercy Corps, Women’s World Banking

- Facebook's Libra could threaten the global financial system (Sky News) — "it's effectively reinvented PayPal, only with Facebook Pounds instead of regular ones."

- Why We’re Joining the Libra Association (Spotify) — "One challenge for Spotify and its users around the world has been the lack of easily accessible payment systems."

- The real risk of Facebook’s Libra coin is crooked developers (TechCrunch) — "A shady developer could build a wallet that just cleans out a user’s account or funnels their coins to the wrong recipient, mines their purchase history for marketing data or uses them to launder money. Digital risks become a lot less abstract when real-world assets are at stake."

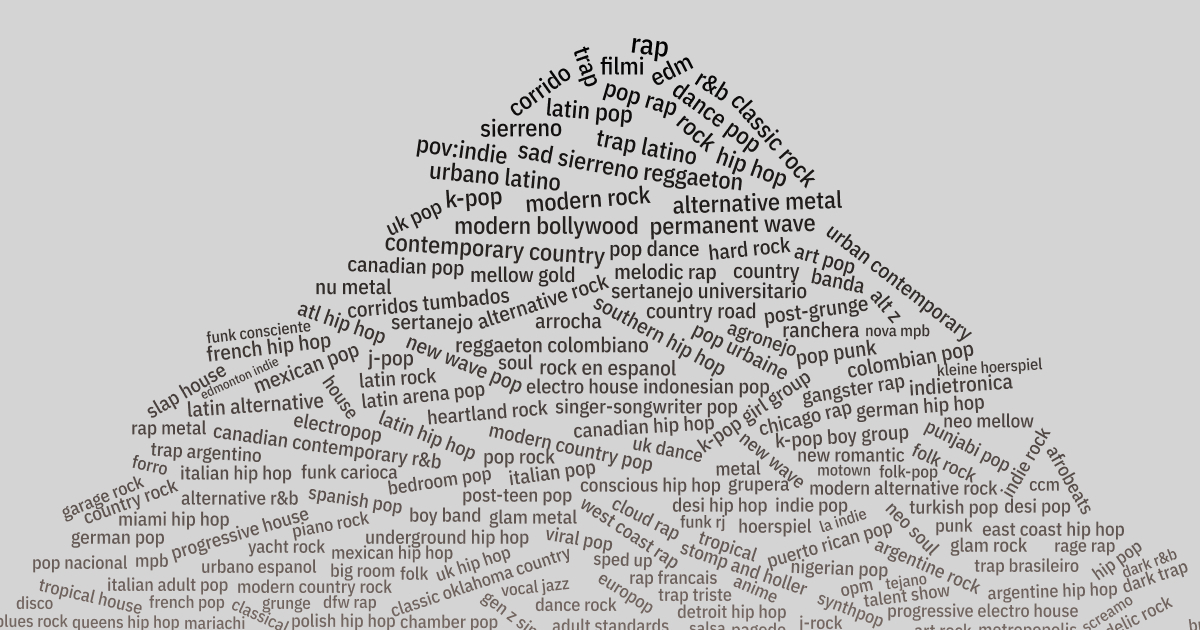

Dynamic ontologies and music genres

As a music lover and someone who has more than a passing interest in dynamic ontologies, I found this analysis of Spotify’s changing categorisation of genres fascinating.

Spotify Unwrapped shows users their most-streamed artists, tracks, and genres at the end of the year. But what if you want to find out at another time? I just had a look at Chosic, which told me that my main ‘parent genres’ are Hip hop, Pop, and Electronic. My top sub-genres are trip hop, downtempo, and electronica.

All of the pushback against genre classifications are valid, whether that's inventing escape room and stomp & holler of what qualifies as r&b vs. pop.Source: You should look at this chart about music genres | pudding.coolBut I still think an always-updating catalog of 6,000 genres is groundbreaking.

I see this effort in the same way I see taxonomy: technically accurate, colloquially useless.

For centuries we had generic names to identify animals, such as “fish.” Everything from squid to crabs (and obviously jellyfish) were lumped into the same “fish” bucket.

But on closer inspection, most of these animals were not related at all. In a research context, scientists have draw boundaries between animals that we mindlessly lumped together.

Similarly, the genre database adds much needed detail to broad categories, like hip hop and rock. For musicologists, it’s an anthropological gold mine. And for Spotify, it likely helps them to better profile their users' music tastes.

But these genres don’t necessarily work in casual conversation: you can describe your music taste as indie, even if, technically, Spotify says it’s escape room. The same goes for biology: people should call figs a fruit, even though it’s technically an inverted flower.

The album is no longer the unit of musical currency

I’m sitting listening to the new Kings of Convenience album while writing this. As this article points out, listening to albums is an increasingly unlikely thing to in the era of streaming music services.

This isn’t accidental: it’s easy to hop between services when the unit of currency is an ‘album’. But when it’s a regularly-updated playlist that’s only available on a particular platform (e.g. Spotify) that’s a different proposition altogether.

To help listeners find their way in the endless aisles of digital music, streaming providers created playlists — but this new way of listening has created unintended consequences for artists and songwriters. Today, three services make up two-thirds of the streaming economy: Spotify, which has an estimated 32 percent of the market, Apple Music (18 percent), and Amazon Music (14 percent). But Spotify dominates the conversation both because of its market power and its immensely popular playlists. In 2017, 68 percent of all listening on Spotify was from a company or user playlist, according to the company’s 2018 Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Its platform has more than 4 billion playlists, 3,000 of which are owned by Spotify, curated by a mix of algorithms and editors.Source: How streaming made hit songs more important than the pop stars who sing them | VoxIts most prominent playlists have serious cultural power. RapCaviar shapes the sound of hip-hop, and can turn indie rappers into household names. The genre-agnostic, slightly quirky playlist Lorem curates the vibe for Spotify’s Gen Z listeners. In 2020, listeners ages 16 to 40 used playlists as their primary source for discovering new music on the platform, according to the company. So today, a placement atop one of its playlists can make or break a song.

Spotify isn’t shy about the marketing power of its playlists. In its SEC filing, the company wrote as much, crediting Lorde’s breakout global success to her placement on a single playlist: Sean Parker’s Hipster International. But her example may be an outlier. The challenge for most artists is that playlist listeners frequently don’t know who they’re listening to. A song with high completion rates on a playlist might end up on more playlists, accumulating millions of streams for an artist who remains effectively nameless. In the best-case scenario, these streams, which pay very low royalties compared to radio, could help land the song a coveted advertisement, or better yet, pique the attention of Top 40 radio programmers.

The habit of sardonic contemplation is the hardest habit of all to break

Angela Carter with the story of my life there. I can't help but be skeptical about 'Libra', Facebook's new crytocurrency project. I'm skeptical about almost all cryptocurrencies, to be honest.

The website is marketing. It's all about 'empowering' the 'unbanked' worldwide. However, let's dive into the white paper:

Members of the Libra Association will consist of geographically distributed and diverse businesses, nonprofit and multilateral organizations, and academic institutions. The initial group of organizations that will work together on finalizing the association’s charter and become “Founding Members” upon its completion are, by industry:

We hope to have approximately 100 members of the Libra Association by the target launch in the first half of 2020.

So, all the usual suspects. How will Facebook ensure that we don't see the crazy price volatility we've seen with other cryptocurrencies?

Libra is designed to be a stable digital cryptocurrency that will be fully backed by a reserve of real assets — the Libra Reserve — and supported by a competitive network of exchanges buying and selling Libra. That means anyone with Libra has a high degree of assurance they can convert their digital currency into local fiat currency based on an exchange rate, just like exchanging one currency for another when traveling. This approach is similar to how other currencies were introduced in the past: to help instill trust in a new currency and gain widespread adoption during its infancy, it was guaranteed that a country’s notes could be traded in for real assets, such as gold. Instead of backing Libra with gold, though, it will be backed by a collection of low-volatility assets, such as bank deposits and short-term government securities in currencies from stable and reputable central banks.

So it sounds like all of the value is being extracted by founding members. Now let's move onto the technology. Any surprises there? Nope.

Blockchains are described as either permissioned or permissionless in relation to the ability to participate as a validator node. In a “permissioned blockchain,” access is granted to run a validator node. In a “permissionless blockchain,” anyone who meets the technical requirements can run a validator node. In that sense, Libra will start as a permissioned blockchain.

This is as conservative as they come, which is exactly what your strategy would be if you're trying to transfer the entire monetary system to one that you control. People often joke about Facebook as 'social infrastructure', but this is a level beyond. This is Facebook as financial infrastructure.

Given both current and potential future regulatory oversight, Facebook are very careful to distance themselves from Libra. In fact, the website proudly states that, "The Libra Association is an independent, not-for-profit membership organization, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland."

To be fair,Josh Constine, writing for TechCrunch, notes that Facebook only gets one vote as a founding member of the Libra Association. It does actually look like they're in it for the long-haul:

In cryptocurrencies, Facebook saw both a threat and an opportunity. They held the promise of disrupting how things are bought and sold by eliminating transaction fees common with credit cards. That comes dangerously close to Facebook’s ad business that influences what is bought and sold. If a competitor like Google or an upstart built a popular coin and could monitor the transactions, they’d learn what people buy and could muscle in on the billions spent on Facebook marketing. Meanwhile, the 1.7 billion people who lack a bank account might choose whoever offers them a financial services alternative as their online identity provider too. That’s another thing Facebook wants to be.

John Constine

Whereas before there's always been social pressure to have a Facebook account, now there could be pressures that span identity and economic necessities, too.

Some good commentary on the hurdles ahead comes from Kari Paul for The Guardian, who writes:

The company claims it will not attempt to bypass existing regulation but instead “innovate” on regulatory fronts. Libra will use the same verification and anti-fraud processes that banks and credit cards use and will implement automated systems to detect fraud, Facebook said in its launch. It also promised to give refunds to any users who are hacked or have Libra stolen from their digital wallets.

Kari Paul

Would this be the same kind of 'innovation' that Uber uses to muscle its way into cities without a license? Or to muscle its way into cities without a license? Perhaps it's the shady business practices beloved of PayPal? Both companies are founding members, after all!

Right now, developers can get access to a 'test network' for Libra. The system itself won't be running until the end of 2020, so there's a lot speculation. Here's some sources I found useful, but you'll need to make up your own mind. Is this a good thing?