- Reinforcement of the connection between productivity and human value

- Creation of 'bullshit jobs'

- Could deny people chance to engage in other pursuits (if poorly implemented)

- Potential to leave behind prior who cannot work (disability / other health concerns)

- Seems didactic and disciplinary

Superorganisms and solidarity

I haven’t gone enough into Buddhism to understand whether what is described in this article by Richard D. Bartlett constitutes as secular version of it, but from my limited knowledge, it would appear so.

That’s not in any way to downplay the important insights that Rich brings to the fore in his writing. For example, asking the question about group dynamics when some or all of the group drinks strong coffee. Or wondering what the largest group is that can hold a single conversation.

Fascinating stuff, and firmly in the realm of philosophy of conviviality and solidarity. One to return to.

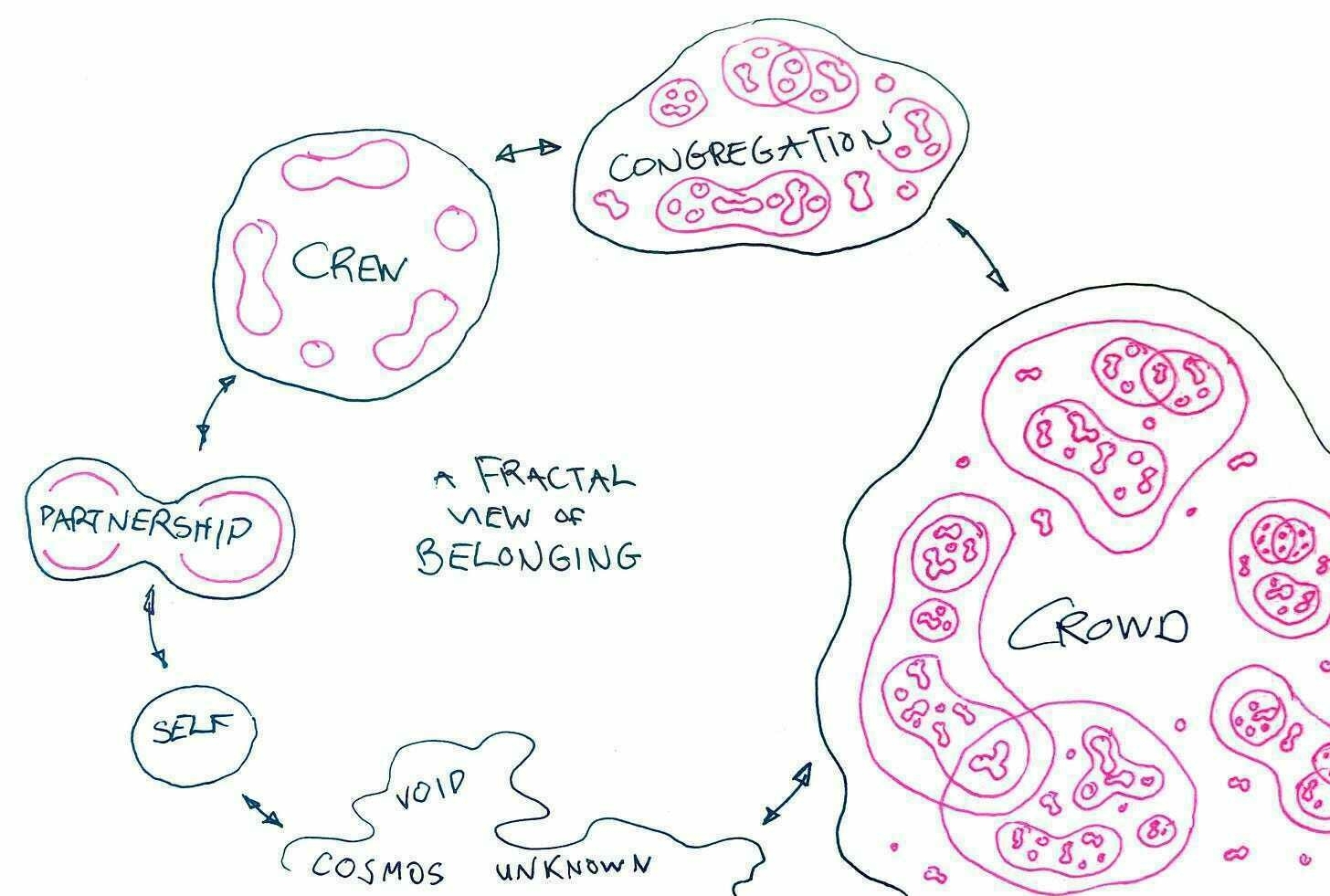

I want you to see your self as a superorganism. And I want you to see the superorganisms that you are part of. I want the perceived boundaries of your self to leak.Source: Seeing Like a Superorganism | Richard D. BartlettI want you to see how your agency is not a tidy black box contained inside the envelope of your skin, but distributed in a network, intra-penetrating with other people. I want you to feel the incorporeal beings steering your choices, and I want you to learn that you can steer their choices too.

[…]

Just as a we can see the distinct layers of “cell”, “tissue” and “organ” at the micro-scales, I want you to see the distinct layers at the macro-scale. I want you to see that a group of 5 people is a distinct superorganism with distinct competencies. A group of 150 people is another species of superorganism, it can do other things.

You may be thinking to yourself, what the fuck are you talking about Rich? I can’t explain it, you have to see for yourself. Maybe I can give you some instructions to help you see like a superorganism.

Worker-owned co-op federation

Sion Whellens helped us set up WAO six years ago, and he’s quoted in this piece about a new worker co-op federation.

There’s been a feeling for a while that Coops UK only really represents large co-operatives such as food co-ops. So this new organisation, of which we will be a member, should be much better at giving worker-owned co-ops a voice.

The vision of the organisation (the name is still under discussion) is to bring together an alliance of people and organisations “with an explicit focus on worker issues, worker-led organising, social solidarity, and economic justice”.Source: New federation planned for worker co-ops in the UK | Co-operative News[…]

The new federation is starting out small – there are around 400 worker co-ops in the UK – but is receiving support and guidance from other federations worldwide, including the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives. “USFWC is a relatively new organisation that has managed to pull together something that works really effectively with little core resource in terms of membership subscriptions. They don’t have a vast amount of rich work co-ops to fund it, so they have to pull resources together in different ways. We can learn from that,” says Mr Whellens.

[…]

Co-operatives UK has been a home for worker co-ops for 20 years, but Mr Whellens believes that over the last decade, there has been “a growing realisation that it can’t really speak about worker co-operation authentically, or develop the worker co-op-specific resources we really need”.

[…]

“There has been a progressive loss of a distinctive voice and service for worker co-ops and we reached a point where we realised we need an independent voice and an independent network that can be more agile, less bureaucratic, more focused on the primary audience for worker co-operation – which is workers.”

We have it in our power to begin the world over again

UBI, GDP, and Libertarian Municipalism

It's sobering to think that, in years to come, historians will probably refer to the 75 years between the end of the Second World War and the start of this period we've just begun with a single name.

Whatever we end up calling it, one thing is for sure: what comes next can't be a continuation of what went before. We need a sharp division of life pre- and post-pandemic.

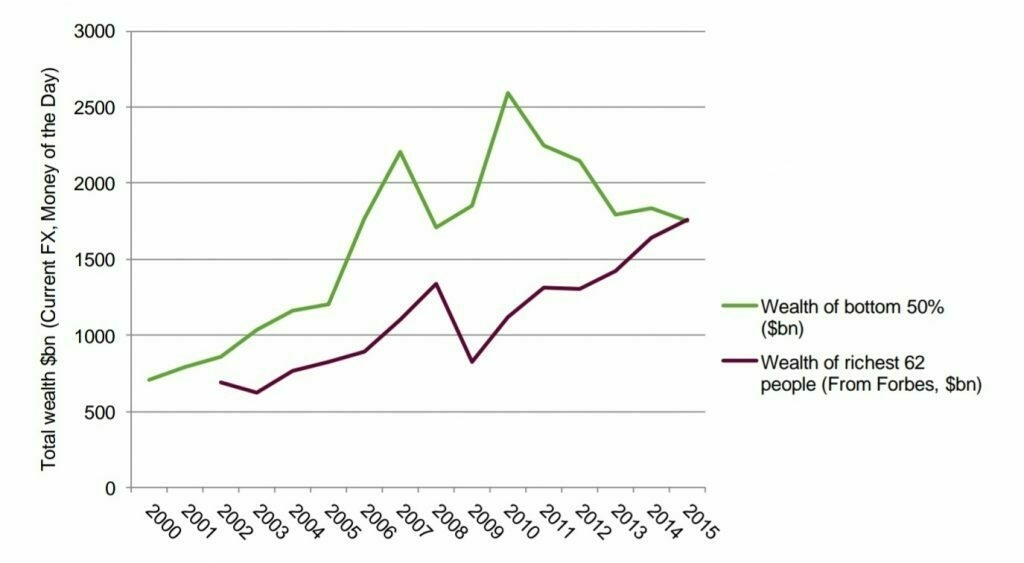

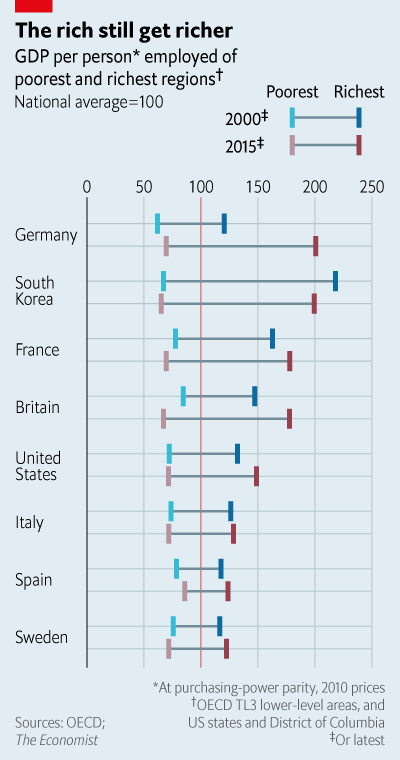

That's because our societies have been increasingly unequal since 2008, when the global financial crisis meant that the rich consolidated their position while the rest of us paid for the mistakes of bankers and the global elite.

So what can we do about this? What should we be demanding once we're allowed back out of our houses? What should we organise against?

I've been a proponent of Universal Basic Income over the last few years, but, I have to say that the closer it comes to being a reality, the more concerns I have about its implementation. Even if it's brought in by a left-leaning government, there's still the danger that it's subsequently used as a weapon against the poor by a new adminstration.

That's why I was interested in this section from a book I'm reading at the moment. Writing in Future Histories, Lizzie O'Shea suggests that we need to think beyond UBI to include other approaches:

Alongside this, we need to consider how productive, waged work could be more democratically organized to meet the needs of society rather than individual companies. To this end, one commonly suggested alternative to a basic income is a job guarantee. The idea is that the government offers a job to anyone who wants one and is able to work, in exchange for a minimum wage. Jobs could be created around infrastructure projects, for example, or care work. Government spending on this enlarged public sector world act like a kind of Keynesian expenditure, to stimulate the economy and buffer the population against the volatility of the private labor market. Modeling suggests that this would be more cost-effective than a basic income (often critiqued for being too expensive) and avoid many of the inflationary perils that might accompany basic income proposals. It could also be used to jump-start sections of the economy that are politically important, like green energy, carbon reduction and infrastructure. A job guarantee could help us collectively decide what kind of work is must urgent and necessary and to prioritize that through democratically accountable representatives.

Lizzie O'Shea, Future Histories

Of course, as she points out, there are a number of drawbacks to a job guarantee scheme:

Nevertheless, O'Shea believes that a combination of a job guarantee, UBI, and government-provided services is the way forward:

Ultimately, we need a combination of these programs. We need the liberty offered by a basic income, the sustainability promised by the organization of a job guarantee, and the protection of dignity offered by centrally planned essential services. It is like a New Deal for the age of automation, a ground rent for the digital revolution, in which the benefits of accelerated productive capacity are shared among everyone. From each according to his ability, to each according to their need - a twenty-first-century vision of socialism. "We have it in our power to begin the world over again," wrote Thomas Paine in an appendix to Common Sense, just before one of the most revolutionary periods in human history. We have a similar opportunity today.

Lizzie O'Shea, Future Histories

While I don't disagree that we will continue to need "the protection of dignity offered by centrally planned essential services," I'm not so sure that giving the state so much power over our lives is a good thing. I think this approach papers over the cracks of neoliberalism, giving billionaires and capitalists a get-out-of-jail-free card.

Instead, I'd like to see a post-pandemic breakup of mega corporations. While a de jure limit on how much one individual or one organisation can be worth is likely to be unworkable, there's ways we can make de facto limits on this a reality.

People respond to incentives, including how easy or hard it is to do something. I know from experience how easy it is to set up a straightforward limited company in the UK and how difficult it is to set up a co-operative. To get to where we need to be, we need to ensure collective decision-making is the norm within organisations owned by workers. And then these worker-owned organisations need to co-ordinate for the good of everyone.

I'm a huge believer in decentralisation, not just technologically but politically and socially; we don't need governments, billionaires, or celebrities telling us what to do with our lives. We need to think wider and deeper. My current thinking aligns with this section on libertarian municipalism from the Wikipedia page on the political philosopher Murray Bookchin:

Libertarian Municipalism constitutes the politics of social ecology, a revolutionary effort in which freedom is given institutional form in public assemblies that become decision-making bodies.

Wikipedia

...or, in other words:

The overriding problem is to change the structure of society so that people gain power. The best arena to do that is the municipality—the city, town, and village—where we have an opportunity to create a face-to-face democracy.

Wikipedia

Some people think that, in these days of super-fast connections to anyone on the planet, that nation states are dead, and that we should be building communities on the blockchain. I have yet to see a proposal of how this would be workable in practice; everything I've seen so far extrapolates naïvely from what's technically possible to what should be socially desirable.

Yes, we can and should have solidarity with people around the world with whom we work and socialise. But this does not negate the importance of decision-making at a local level. Gaming clans don't yet do bin collections, and colleagues in a different country can't fix the corruption riddling your local government.

Ultimately, then, we're going to need a whole new politics and social contract after the pandemic. I sincerely hope we manage to grasp the nettle and do something radically different. I'm not sure how we'll all survive if the rich, once again, come out of all this even richer than before.

BONUS: check out this 1978 speech from Murray Bookchin where he calls for utopia, not futurism.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup, become a supporter, or download Thought Shrapnel Vol.1: Personal Productivity!

Quotation-as-title from Thomas Paine. Header image by Stas Knop.