- Schools

- Volunteering

- Offices

- House prices

- Community cohesion

- High street

- Home delivery

- Why Do You Grab Your Bag When Running Off a Burning Plane? (The New York Times) — it turns out that it's less of a decision, more of an impulse.

- If a house was designed by machine, how would it look? (BBC Business) — lighter, more efficient buildings.

- Playdate is an adorable handheld with games from the creators of Qwop, Katamari, and more (The Verge) — a handheld console with a hand crank that's actually used for gameplay instead of charging!

- The true story of the worst video game in history (Engadget) — it was so bad they buried millions of unsold cartridges in the desert.

- E Ink Smartphones are the big new trend of 2019 (Good e-Reader) — I've actually also own a regular phone with an e-ink display, so I can't wait for this to be a thing.

- Motorola Moto Z2 Force - Toughness score: 8.5/10

- LG X Venture - Toughness score: 6.6/10

- Apple iPhone X - Toughness score: 6.2/10

- LG V30 - Toughness score: 6/10

- Samsung Galaxy S9 - Toughness score: 6/10

- Motorola Moto G5 Plus - Toughness score: 5.1/10

- Apple iPhone 8 - Toughness score: 4.9/10

- Samsung Galaxy Note 8 - Toughness score: 4.3/10

- OnePlus 5T - Toughness score: 4.3/10

- Huawei Mate 10 Pro - Toughness score: 4.3/10

- Google Pixel 2 XL - Toughness score: 4.3/10

- iPhone SE - Toughness score: 3.9/10

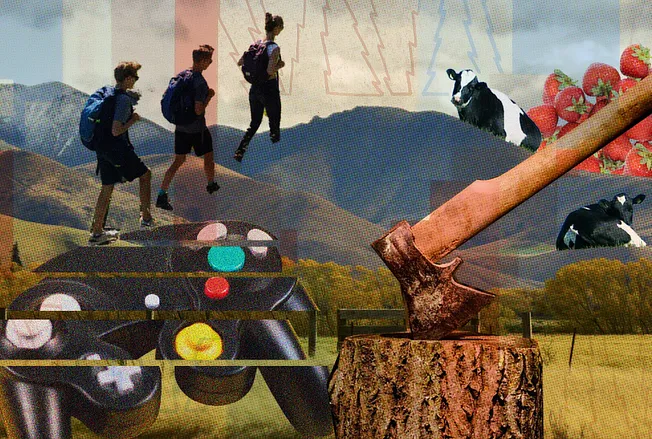

Taking screenagers to the forest

As a parent of a 16 year-old boy and 12 year-old girl I found this article fascinating. Written by Caleb Silverberg, now 17 years of age, it describes his decision to break free from his screen addiction and enrol in Midland, an experiential boarding school located in a forest where technology is forbidden.

Trading his smartphone for an ax, he found liberation and genuine human connection through chores like chopping firewood, living off the land, and engaging in face-to-face conversations. Silverberg advocates for a “Technology Shabbat,” a periodic break from screens, as a solution for his generation’s screen-related issues like ADHD and depression.

At 15 years old, I looked in the mirror and saw a shell of myself. My face was pale. My eyes were hollow. I needed a radical change.Source: Why I Traded My Smartphone for an Ax | The Free PressI vaguely remembered one of my older sister’s friends describing her unique high school, Midland, an experiential boarding school located in the Los Padres National Forest. The school was founded in 1932 under the belief of “Needs Not Wants.” In the forest, cell phones and video games are forbidden, and replaced with a job to keep the place running: washing dishes, cleaning bathrooms, or sanitizing the mess hall. Students depend on one another.

[…]

September 2, 2021, was my first day at Midland, when I traded my smartphone for an ax.

At Midland, students must chop firewood to generate hot water for their showers and heat for their cabins and classrooms. If no one chops the wood or makes the fire, there’s a cold shower, a freezing bed, or a chilly classroom. No punishment by a teacher or adult. Just the disappointment of your peers. Your friends.

[…]

Before Midland, whenever I sat on the couch, engrossed in TikTok or Instagram, my parents would caution me: “Caleb, your brain is going to melt if you keep staring at that screen!” I dismissed their concerns at first. But eventually, I experienced life without an electronic device glued to my hand and learned they were right all along.

[…]

I have been privileged to attend Midland. But anyone can benefit from its lessons. To my generation, I would like to offer a 5,000-year-old solution to our twenty-first-century dilemma. Shabbat is the weekly sabbath in Judaic custom where individuals take 24 hours to rest and relax. This weekly reset allows our bodies and minds to recharge.

Study shows no link between age at getting first smartphone and mental health issues

Where we live is unusual for the UK: we have first, middle, and high schools. The knock-on effect of this in the 21st century is that kids aged nine years old are walking to school and, often, taking a smartphone with them.

This study shows that the average age children were given a phone by parents was 11.6 years old, which meshes with the ‘norm’ (I would argue) in the UK of giving kids one when they go to secondary school.

What I like about these findings are that parents overall seem to do a pretty good job. It’s been a constant battle with our eldest, who is almost 16, to be honest, but I think he’s developed some useful habits around technology.

Parents fretting over when to get their children a cell phone can take heart: A rigorous new study from Stanford Medicine did not find a meaningful association between the age at which kids received their first phones and their well-being, as measured by grades, sleep habits and depression symptoms.Source: Age that kids acquire mobile phones not linked to well-being, says Stanford Medicine study | Stanford Medicine[…]

The research team followed a group of low-income Latino children in Northern California as part of a larger project aimed to prevent childhood obesity. Little prior research has focused on technology acquisition in non-white or low-income populations, the researchers said.

The average age at which children received their first phones was 11.6 years old, with phone acquisition climbing steeply between 10.7 and 12.5 years of age, a period during which half of the children acquired their first phones. According to the researchers, the results may suggest that each family timed the decision to what they thought was best for their child.

“One possible explanation for these results is that parents are doing a good job matching their decisions to give their kids phones to their child’s and family’s needs,” Robinson said. “These results should be seen as empowering parents to do what they think is right for their family.”

Dedicated portable digital media players and central listening devices

I listen to music. A lot. In fact, I’m listening while I write this (Busker Flow by Kofi Stone). This absolutely rinses my phone battery unless it’s plugged in, or if I’m playing via one of the smart speakers in every room of our house.

I’ve considered buying a dedicated digital media player, specifically one of the Sony Walkman series. But even the reasonably-priced ones are almost the cost of a smartphone and, well, I carry my phone everywhere.

It’s interesting, therefore, to see Warren Ellis' newsletter shoutout being responded to by Marc Weidenbaum. It seems they both have dedicated ‘music’ screens on their smartphones. Personally, I use an Android launcher that makes that impracticle. Also, I tend to switch between only four apps: Spotify (I’ve been a paid subscriber for 13 years now), Auxio (for MP3s), BBC Sounds (for radio/podcasts), and AntennaPod (for other podcasts). I don’t use ‘widgets’ other than the player in the notifications bar, if that counts.

We are too busy mopping the floor to turn off the faucet

Pandemics, remote work, and global phase shifts

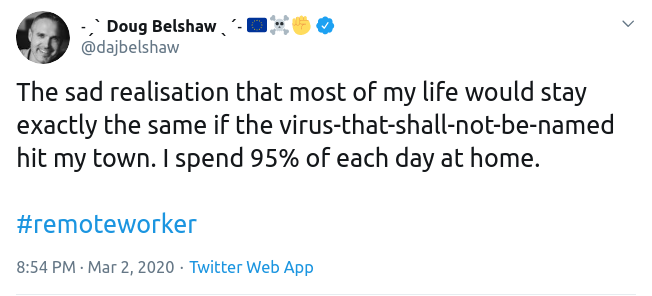

Last week, I tweeted this:

I get the feeling that, between film and TV shows on Netflix, Amazon deliveries, and social interaction on Twitter and Mastodon, beyond close friends and family, no-one would even realise if I'd been quarantined.

Writing in The Atlantic, Ian Bogost points out that Every Place Is the Same Now, because you go to every place with your personal screen, a digital portal to the wider world.

Anywhere has become as good as anywhere else. The office is a suitable place for tapping out emails, but so is the bed, or the toilet. You can watch television in the den—but also in the car, or at the coffee shop, turning those spaces into impromptu theaters. Grocery shopping can be done via an app while waiting for the kids’ recital to start. Habits like these compress time, but they also transform space. Nowhere feels especially remarkable, and every place adopts the pleasures and burdens of every other. It’s possible to do so much from home, so why leave at all?

Ian Bogost (The Atlantic)

If you're a knowledge worker, someone who deals with ideas and virtual objects rather than things in 'meatspace', then there is nothing tying you to a particular geographical place. This may be liberating, but it's also quite... weird.

It’s easy but disorienting, and it makes the home into a very strange space. Until the 20th century, one had to leave the house for almost anything: to work, to eat or shop, to entertain yourself, to see other people. For decades, a family might have a single radio, then a few radios and a single television set. The possibilities available outside the home were far greater than those within its walls. But now, it’s not merely possible to do almost anything from home—it’s also the easiest option. Our forebears’ problem has been inverted: Now home is a prison of convenience that we need special help to escape.

Ian Bogost (The Atlantic)

I've worked from home for the last eight years, and now can't imagine going back to working any other way. Granted, I get to travel pretty much every month, but that 95% being-at-home statistic still includes my multi-day international trips.

I haven't watched it recently, but in 2009 a film called Surrogates starring Bruce Willis foreshadowed the kind of world we're creating. Here's the synopsis via IMDB:

People are living their lives remotely from the safety of their own homes via robotic surrogates — sexy, physically perfect mechanical representations of themselves. It's an ideal world where crime, pain, fear and consequences don't exist. When the first murder in years jolts this utopia, FBI agent Greer discovers a vast conspiracy behind the surrogate phenomenon and must abandon his own surrogate, risking his life to unravel the mystery.

IMDB

If we replace the word 'robotic' with 'virtual' in this plot summary, then it's a close approximation to the world in which some of us now live. Facetuned Instagram selfies project a perfect life. We construct our own narratives and then believe the story we have concocted. Everything is amazing but no-one's happy.

Even Zoom, the videoconferencing software I use most days for work, has an option to smooth out wrinkles, change your background, and make everything look a bit more sparkly. Our offline lives can be gloriously mundane, but online, thanks to various digital effects, we can make them look glorious. And why wouldn't we?

I think we'll see people and businesses optimising for how they look and sound online, including recruitment. The ability to communicate effectively at a distance with people who you may never meet in person is a skill that's going to be in high demand, if it isn't already.

Remote working may be a trend, but one which is stubbornly resisted by some bosses who are convinced they have to keep a close eye on employees to get any work out of them.

However, when those bosses are forced to implement remote working policies to keep their businesses afloat, and nothing bad happens as a result, this attitude can, and probably will, change. Remote working, when done properly, is not only more cost-effective for businesses, but often leads to higher productivity and self-reported worker happiness.

Being 'good in the room' is fine, and I'm sure it will always be highly prized, but I also see confident, open working practices as something that's rising in perceived value. Chairing successful online meetings is at least as important as chairing ones offline, for example. We need to think of ways of being able recognise these remote working skills, as it's not something in which you can receive a diploma.

For workers, of course, there are so many benefits of working from home that I'm not even sure where to start. Your health, relationships, and happiness are just three things that are likely to dramatically improve when you start working remotely.

For example, let's just take the commute. This dominates the lives of non-remote workers, usually taking an hour or more out of a their day — every day. Commuting is tiring and inconvenient, but people are currently willing to put up with long commutes to afford a decently-sized house, or to live in a nicer area.

So, let's imagine that because of the current pandemic (which some are calling the world's biggest remote-working experiment) businesses decide that having their workers being based from home has multi-faceted benefits. What happens next?

Well, if a large percentage (say we got up to ~50%) of the working population started working remotely over the next few months and years, this would have a knock-on effect. We'd see changes in:

...to name but a few. I think it would be a huge net benefit for society, and hopefully allow for much greater civic engagement and democratic participation.

I'll conclude with a quotation from Nafeez Ahmed's excellent (long!) post on what he's calling a global phase shift. Medium says it's a 30-minute read, but I reckon it's about half that.

Ahmed points out in stark detail the crisis, potential future scenarios, and the opportunity we've got. I particularly appreciate his focus on the complete futility of what he calls "a raw, ‘fend for yourself’ approach". We must work together to solve the world's problems.

The coronavirus outbreak is, ultimately, a lesson in not just the inherent systemic fragilities in industrial civilization, but also the limits of its underlying paradigm. This is a paradigm premised on a specific theory of human nature, the neoclassical view of Homo-Economicus, human beings as dislocated units which compete with each other to maximise their material self-gratification through endless consumption and production. That paradigm and its values have brought us so far in our journey as a species, but they have long outlasted their usefulness and now threaten to undermine our societies, and even our survival as a species.

Getting through coronavirus will be an exercise not just in building societal resilience, but relearning the values of cooperation, compassion, generosity and kindness, and building systems which institutionalize these values. It is high time to recognize that such ethical values are not simply human constructs, products of socialization. They are cognitive categories which reflect patterns of behaviour in individuals and organizations that have an evolutionary, adaptive function. In the global phase shift, systems which fail to incorporate these values into their structures will eventually die.

Nafeez Ahmed

Just as crises can be manufactured by totalitarian regimes to seize power and control populations, perhaps natural crises can be used to make us collectively realise we need to pull together?

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup, become a supporter, or download Thought Shrapnel Vol.1: Personal Productivity!

Header image by pan xiaozhen. Anonymous quotation-as-title taken from Scott Klososky's The Velocity Manifesto

Friday fumblings

These were the things I came across this week that made me smile:

Image via Why WhatsApp Will Never Be Secure (Pavel Durov)

The dangers of distracted parenting

I usually limit myself to three quotations in posts I write here. I’m going to break that self-imposed rule for this article by Erika Christakis in The Atlantic on parents' screentime.

Christakis points out the good and the bad news:

Yes, parents now have more face time with their children than did almost any parents in history. Despite a dramatic increase in the percentage of women in the workforce, mothers today astoundingly spend more time caring for their children than mothers did in the 1960s. But the engagement between parent and child is increasingly low-quality, even ersatz. Parents are constantly present in their children’s lives physically, but they are less emotionally attuned.As parents, and in society in general, we're super-hot on limiting kids' screentime, but we don't necessarily apply that to ourselves:

[S]urprisingly little attention is paid to screen use by parents... who now suffer from what the technology expert Linda Stone more than 20 years ago called “continuous partial attention.” This condition is harming not just us, as Stone has argued; it is harming our children. The new parental-interaction style can interrupt an ancient emotional cueing system, whose hallmark is responsive communication, the basis of most human learning. We’re in uncharted territory.'Continuous partial attention' is the term people tend to use these days instead of 'multitasking'. To my mind it's a better term, as it references the fact that you're not just trying to do different things simultaneously, you're trying to pay attention to them.

I’ve given the example before of my father sitting down to read the newspaper on a Sunday. Is there really much difference to the child, I’ve wondered, between his being hidden behind a broadsheet for an hour, and his scrolling and clicking on a mobile device? In some ways yes, in some ways no.

To me, the difference can be summed up quite easily: our mobile devices are designed to be addictive and capture our full attention, in ways that analogue media and experiences aren't.It has never been easy to balance adults’ and children’s needs, much less their desires, and it’s naive to imagine that children could ever be the unwavering center of parental attention. Parents have always left kids to entertain themselves at times—“messing about in boats,” in a memorable phrase from The Wind in the Willows, or just lounging aimlessly in playpens. In some respects, 21st-century children’s screen time is not very different from the mother’s helpers every generation of adults has relied on to keep children occupied. When parents lack playpens, real or proverbial, mayhem is rarely far behind. Caroline Fraser’s recent biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, the author of Little House on the Prairie, describes the exceptionally ad hoc parenting style of 19th-century frontier parents, who stashed babies on the open doors of ovens for warmth and otherwise left them vulnerable to “all manner of accidents as their mothers tried to cope with competing responsibilities.” Wilder herself recounted a variety of near-calamities with her young daughter, Rose; at one point she looked up from her chores to see a pair of riding ponies leaping over the toddler’s head.

Short, deliberate separations can of course be harmless, even healthy, for parent and child alike (especially as children get older and require more independence). But that sort of separation is different from the inattention that occurs when a parent is with a child but communicating through his or her nonengagement that the child is less valuable than an email. A mother telling kids to go out and play, a father saying he needs to concentrate on a chore for the next half hour—these are entirely reasonable responses to the competing demands of adult life. What’s going on today, however, is the rise of unpredictable care, governed by the beeps and enticements of smartphones. We seem to have stumbled into the worst model of parenting imaginable—always present physically, thereby blocking children’s autonomy, yet only fitfully present emotionally.Physically present but emotionally unavailable. Yes, we need to do better.

Under the circumstances, it’s easier to focus our anxieties on our children’s screen time than to pack up our own devices. I understand this tendency all too well. In addition to my roles as a mother and a foster parent, I am the maternal guardian of a middle-aged, overweight dachshund. Being middle-aged and overweight myself, I’d much rather obsess over my dog’s caloric intake, restricting him to a grim diet of fibrous kibble, than address my own food regimen and relinquish (heaven forbid) my morning cinnamon bun. Psychologically speaking, this is a classic case of projection—the defensive displacement of one’s failings onto relatively blameless others. Where screen time is concerned, most of us need to do a lot less projecting.Amen to that.

Source: The Atlantic (via Jocelyn K. Glei)

The dangers of distracted parenting

I usually limit myself to three quotations in posts I write here. I’m going to break that self-imposed rule for this article by Erika Christakis in The Atlantic on parents' screentime.

Christakis points out the good and the bad news:

Yes, parents now have more face time with their children than did almost any parents in history. Despite a dramatic increase in the percentage of women in the workforce, mothers today astoundingly spend more time caring for their children than mothers did in the 1960s. But the engagement between parent and child is increasingly low-quality, even ersatz. Parents are constantly present in their children’s lives physically, but they are less emotionally attuned.As parents, and in society in general, we're super-hot on limiting kids' screentime, but we don't necessarily apply that to ourselves:

[S]urprisingly little attention is paid to screen use by parents... who now suffer from what the technology expert Linda Stone more than 20 years ago called “continuous partial attention.” This condition is harming not just us, as Stone has argued; it is harming our children. The new parental-interaction style can interrupt an ancient emotional cueing system, whose hallmark is responsive communication, the basis of most human learning. We’re in uncharted territory.'Continuous partial attention' is the term people tend to use these days instead of 'multitasking'. To my mind it's a better term, as it references the fact that you're not just trying to do different things simultaneously, you're trying to pay attention to them.

I’ve given the example before of my father sitting down to read the newspaper on a Sunday. Is there really much difference to the child, I’ve wondered, between his being hidden behind a broadsheet for an hour, and his scrolling and clicking on a mobile device? In some ways yes, in some ways no.

To me, the difference can be summed up quite easily: our mobile devices are designed to be addictive and capture our full attention, in ways that analogue media and experiences aren't.It has never been easy to balance adults’ and children’s needs, much less their desires, and it’s naive to imagine that children could ever be the unwavering center of parental attention. Parents have always left kids to entertain themselves at times—“messing about in boats,” in a memorable phrase from The Wind in the Willows, or just lounging aimlessly in playpens. In some respects, 21st-century children’s screen time is not very different from the mother’s helpers every generation of adults has relied on to keep children occupied. When parents lack playpens, real or proverbial, mayhem is rarely far behind. Caroline Fraser’s recent biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, the author of Little House on the Prairie, describes the exceptionally ad hoc parenting style of 19th-century frontier parents, who stashed babies on the open doors of ovens for warmth and otherwise left them vulnerable to “all manner of accidents as their mothers tried to cope with competing responsibilities.” Wilder herself recounted a variety of near-calamities with her young daughter, Rose; at one point she looked up from her chores to see a pair of riding ponies leaping over the toddler’s head.

Short, deliberate separations can of course be harmless, even healthy, for parent and child alike (especially as children get older and require more independence). But that sort of separation is different from the inattention that occurs when a parent is with a child but communicating through his or her nonengagement that the child is less valuable than an email. A mother telling kids to go out and play, a father saying he needs to concentrate on a chore for the next half hour—these are entirely reasonable responses to the competing demands of adult life. What’s going on today, however, is the rise of unpredictable care, governed by the beeps and enticements of smartphones. We seem to have stumbled into the worst model of parenting imaginable—always present physically, thereby blocking children’s autonomy, yet only fitfully present emotionally.Physically present but emotionally unavailable. Yes, we need to do better.

Under the circumstances, it’s easier to focus our anxieties on our children’s screen time than to pack up our own devices. I understand this tendency all too well. In addition to my roles as a mother and a foster parent, I am the maternal guardian of a middle-aged, overweight dachshund. Being middle-aged and overweight myself, I’d much rather obsess over my dog’s caloric intake, restricting him to a grim diet of fibrous kibble, than address my own food regimen and relinquish (heaven forbid) my morning cinnamon bun. Psychologically speaking, this is a classic case of projection—the defensive displacement of one’s failings onto relatively blameless others. Where screen time is concerned, most of us need to do a lot less projecting.Amen to that.

Source: The Atlantic (via Jocelyn K. Glei)

The toughest smartphones on the market

I found this interesting:

To help you avoid finding out the horrifying truth when your phone goes clattering to the ground, we tested all of the major smartphones by dropping them over the course of four rounds from 4 feet and 6 feet onto wood and concrete — and even into a toilet — to see which handset is the toughest.The results?

While the result wasn't completely unexpected — after all, the phone has a ShatterShield display, which the company guarantees against cracks — the Moto Z2 Force survived drops from 6 feet onto concrete, with barely a scratch.Summary:Apple’s least-expensive phone didn’t prove very tough at all. In fact, the $399 iPhone SE was rendered unusable before all of the others. However, this was not a big surprise, as the newer iPhone 8 and iPhone X are made with much stronger glass than the iPhone SE’s from 2016.

Every part of your digital life is being tracked, packaged up, and sold

I’ve just installed Lumen Privacy Monitor on my Android smartphone after reading this blog post from Mozilla:

The link to the full report is linked to in the quotation above, but the high-level findings were:New research co-authored by Mozilla Fellow Rishab Nithyanand explores just this: The opaque realm of third-party trackers and what they know about us. The research is titled “Apps, Trackers, Privacy, and Regulators: A Global Study of the Mobile Tracking Ecosystem,” and is authored by researchers at Stony Brook University, Data & Society, IMDEA Networks, ICSI, Princeton University, Corelight, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

[...]In all, the team identified 2,121 trackers — 233 of which were previously unknown to popular advertising and tracking blacklists. These trackers collected personal data like Android IDs, phone numbers, device fingerprints, and MAC addresses.

We're finally getting the stage where a large portion of the population can't really ignore the fact that they're using free services in return for pervasive and always-on surveillance.»Most trackers are owned by just a few parent organizations. The authors report that sixteen of the 20 most pervasive trackers are owned by Alphabet. Other parent organizations include Facebook and Verizon. “There is a clear oligopoly happening in the ecosystem,” Nithyanand says.

» Mobile games and educational apps are the two categories with the highest number of trackers. Users of news and entertainment apps are also exposed to a wide range of trackers. In a separate paper co-authored by Vallina-Rodriguez, he explores the intersection of mobile tracking and apps for youngsters: “Is Our Children’s Apps Learning?”

» Cross-device tracking is widespread. The vast majority of mobile trackers are also active on the desktop web, allowing companies to link together personal data produced in both ecosystems. “Cross-platform tracking is already happening everywhere,” Nithyanand says. “Fifteen of the top 20 organizations active in the mobile advertising space also have a presence in the web advertising space.”

Audrey Watters on technology addiction

Audrey Watters answers the question whether we’re ‘addicted’ to technology:

I am hesitant to make any clinical diagnosis about technology and addiction – I’m not a medical professional. But I’ll readily make some cultural observations, first and foremost, about how our notions of “addiction” have changed over time. “Addiction” is medical concept but it’s also a cultural one, and it’s long been one tied up in condemning addicts for some sort of moral failure. That is to say, we have labeled certain behaviors as “addictive” when they’ve involve things society doesn’t condone. Watching TV. Using opium. Reading novels. And I think some of what we hear in discussions today about technology usage – particularly about usage among children and teens – is that we don’t like how people act with their phones. They’re on them all the time. They don’t make eye contact. They don’t talk at the dinner table. They eat while staring at their phones. They sleep with their phones. They’re constantly checking them.The problem is that our devices are designed to be addictive, much like casinos. The apps on our phones are designed to increase certain metrics:

I think we’re starting to realize – or I hope we’re starting to realize – that those metrics might conflict with other values. Privacy, sure. But also etiquette. Autonomy. Personal agency. Free will.Ultimately, she thinks, this isn't a question of addiction. It's much wider than that:

How are our minds – our sense of well-being, our knowledge of the world – being shaped and mis-shaped by technology? Is “addiction” really the right framework for this discussion? What steps are we going to take to resist the nudges of the tech industry – individually and socially and yes maybe even politically?Good stuff.

Source: Audrey Watters