- Some of your talents and skills can cause burnout. Here’s how to identify them (Fast Company) — "You didn’t mess up somewhere along the way or miss an important lesson that the rest of us received. We’re all dealing with gifts that drain our energy, but up until now, it hasn’t been a topic of conversation. We aren’t discussing how we end up overusing our gifts and feeling depleted over time."

- Learning from surveillance capitalism (Code Acts in Education) — "Terms such as ‘behavioural surplus’, ‘prediction products’, ‘behavioural futures markets’, and ‘instrumentarian power’ provide a useful critical language for decoding what surveillance capitalism is, what it does, and at what cost."

- Facebook, Libra, and the Long Game (Stratechery) — "Certainly Facebook’s audacity and ambition should not be underestimated, and the company’s network is the biggest reason to believe Libra will work; Facebook’s brand is the biggest reason to believe it will not."

- The Pixar Theory (Jon Negroni) — "Every Pixar movie is connected. I explain how, and possibly why."

- Mario Royale (Kottke.org) — "Mario Royale (now renamed DMCA Royale to skirt around Nintendo’s intellectual property rights) is a battle royale game based on Super Mario Bros in which you compete against 74 other players to finish four levels in the top three. "

- Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think (The Atlantic) — "In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s."

- What Happens When Your Kids Develop Their Own Gaming Taste (Kotaku) — "It’s rewarding too, though, to see your kids forging their own path. I feel the same way when I watch my stepson dominate a round of Fortnite as I probably would if he were amazing at rugby: slightly baffled, but nonetheless proud."

- Whence the value of open? (Half an Hour) — "We will find, over time and as a society, that just as there is a sweet spot for connectivity, there is a sweet spot for openness. And that point where be where the default for openness meets the push-back from people on the basis of other values such as autonomy, diversity and interactivity. And where, exactly, this sweet spot is, needs to be defined by the community, and achieved as a consensus."

- How to Be Resilient in the Face of Harsh Criticism (HBR) — "Here are four steps you can try the next time harsh feedback catches you off-guard. I’ve organized them into an easy-to-remember acronym — CURE — to help you put these lessons in practice even when you’re under stress."

- Fans Are Better Than Tech at Organizing Information Online (WIRED) — "Tagging systems are a way of imposing order on the real world, and the world doesn't just stop moving and changing once you've got your nice categories set up."

- MIT Starts University Group to Build New Digital Credential System (EdSurge) — "The group... expects the standard to be “completely complementary” to the Open Badges standard that has been in the works for many years."

- European MOOC Consortium launches Common Micro-credential Framework (Education Technology) — "A leading driver for the development of the framework is the demand from learners to develop new knowledge, skills and competencies from shorter, recognised and quality-assured courses."

- Why a New Kind of ‘Badge’ Stands Out From the Crowd (The Chronicle of Higher Education) — "As we’ve been reporting, the buzz around certificates, badges, and other measures of achievement has been on the rise as employers have increasingly questioned whether a college degree is a reliable or adequate “signal” of an applicant’s capabilities."

Microcast #079 - information environments

This week's microcast is about information environments, the difference between technical and 'people' skills, and sharing your experience.

Show notes

Friday feeds

These things caught my eye this week:

Header image via Dilbert

There’s no perfection where there’s no selection

So said Baltasar Gracián. One of the reasons that e-portfolios never really took off was because there's so much to read. Can you imagine sifting through hundreds of job applications where each applicant had a fully-fledged e-portfolio, including video content?

That's why I've been so interested in Open Badges, and have written plenty on the subject over the last eight years. If you're new to the party, there are various terms such as 'microcredentials', 'digital badges', and 'digital credentials'. The difference is in the standard which was previously stewarded by Mozilla (including at my time there) and now by IMS Global Learning Consortium.

When I left Mozilla, I did a lot of work with City & Guilds, an awarding body that's well known for its vocational qualifications. They took a particular interest in Open Badges, for obvious reasons. In this article for FE News, Kirstie Donnelly (Managing Director of the City & Guilds Group) explains their huge potential:

The fact that you can actually stack these credentials, and they become portable, then you can publish them through online, through your LinkedIn. I just think it puts a very different dynamic into how the learner owns their experience, but at the same time the employers and the education system can still influence very much how those credentials are built and stacked.

Kirstie Donnelly

Like it or not, a lot of education is 'signalling' — i.e. providing an indicator that you can do a thing. The great thing about Open Badges is that you can make credentials much more granular and, crucially, include evidence of your ability to do the thing you claim to be able to do.

As Tyler Cowen picks up on for Marginal Revolution, without this granularity, there's a knock-on effect upon societal inequality. Privilege is perpetuated. He quotes a working paper by Gaurab Aryal, Manudeep Bhuller, and Fabian Lange who state:

The social and the private returns to education differ when education can increase productivity and also be used to signal productivity. We show how instrumental variables can be used to separately identify and estimate the social and private returns to education within the employer learning framework of Farber and Gibbons (1996) and Altonji and Pierret (2001). What an instrumental variable identifies depends crucially on whether the instrument is hidden from or observed by the employers. If the instrument is hidden, it identifies the private returns to education, but if the instrument is observed by employers, it identifies the social returns to education.

Aryal, Bhuller, and Lange

I take this to mean that, in a marketplace, the more the 'buyers' (i.e. employers) understand what's on offer, the more this changes the way that 'sellers' (i.e. potential employees) position themselves. Open Badges and other technologies can help with this.

Understandably, a lot is made of digital credentials for recruitment. Indeed, I've often argued that badges are important at times of transition — whether into a job, on the job, or onto your next job. But they are also important for reasons other than employment.

Lauren Acree, writing for Digital Promise explains how they can be used to foster more inclusive classrooms:

The Learner Variability micro-credentials ask educators to better understand students as learners. The micro-credentials support teachers as they partner with students in creating learning environments that address learners’ needs, leverage their strengths, and empower students to reflect and adjust as needed. We found that micro-credentials are one important way we can ultimately build teacher capacity to meet the needs of all learners.

Lauren Acree

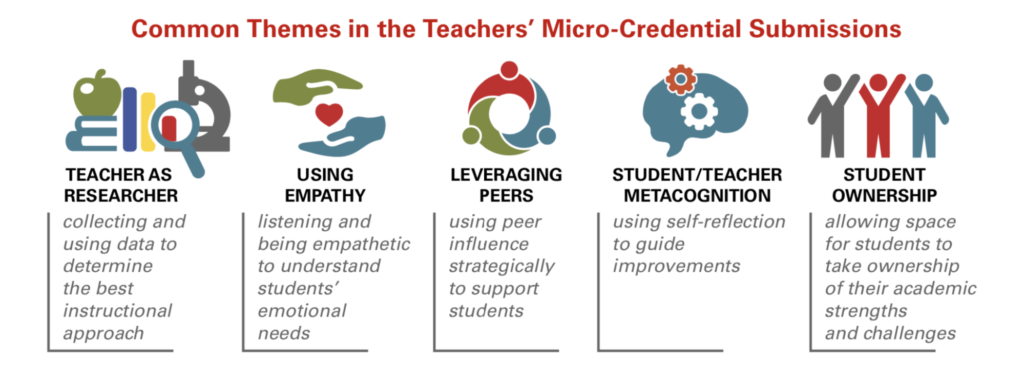

The article includes this image representing a taxonomy of how teachers use micro-credentials in their work:

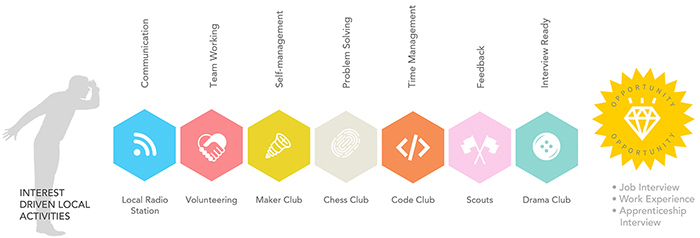

If we zoom out even further, we can see that micro-credentials as a form of 'currency' could play a big role in how we re-imagine society. Tim Riches, who I collaborated with while at both Mozilla and City & Guilds, has written a piece for the RSA about the 'Cities of Learning' projects that he's been involved in. All of these have used badges in some form or other.

In formal education, the value of learning is measured in qualifications. However, qualifications only capture a snapshot of what we know, not what we can do. What’s more, they tend to measure routine skills - the ones most vulnerable to automation and outsourcing.

[...]

Cities are full of people with unrecognised talents and potential. Cities are a huge untapped resource. Skills are developed every day in the community, at work and online, but they are hidden from view - disconnected from formal education and employers.

Tim Riches

I don't live in a city, and don't necessarily see them as the organising force here, but I do think that, on a societal level, there's something about recognising potential. Tim includes a graphic in his article which, I think, captures this nicely:

There's a phrase that's often used by feminist writers: "you can't be what you can't see". In other words, if you don't have any role models in a particular area, you're unlikely to think of exploring it. Similarly, if you don't know anyone who's a lawyer, or a sailor, or a horse rider, it's not perhaps something you'd think of doing.

If we can wrest control of innovations such as Open Badges away from the incumbents, and focus on human flourishing, I can see real opportunities for what Serge Ravet and others call 'open recognition'. Otherwise, we're just co-opting them to prop up and perpetuate the existing, unequal system.

Also check out:

Valuing and signalling your skills

When I rocked up to the MoodleMoot in Miami back in November last year, I ran a workshop that involved human spectrograms, post-it notes, and participatory activities. Although I work in tech and my current role is effectively a product manager for Moodle, I still see myself primarily as an educator.

This, however, was a surprise for some people who didn’t know me very well before I joined Moodle. As one person put it, “I didn’t know you had that in your toolbox”. The same was true at Mozilla; some people there just saw me as a quasi-academic working on web literacy stuff.

Given this, I was particularly interested in a post from Steve Blank which outlined why he enjoys working with startup-like organisations rather than large, established companies:

It never crossed my mind that I gravitated to startups because I thought more of my abilities than the value a large company would put on them. At least not consciously. But that’s the conclusion of a provocative research paper, Asymmetric Information and Entrepreneurship, that explains a new theory of why some people choose to be entrepreneurs. The authors’ conclusion — Entrepreneurs think they are better than their resumes show and realize they can make more money by going it alone.And in most cases, they are right.If you stop and think for a moment, it's entirely obvious that you know your skills, interests, and knowledge better than anyone who hires you for a specific role. Ordinarily, they're interested in the version of you that fits the job description, rather than you as a holistic human being.

The paper that Blank cites covers research which followed 12,686 people over 30+ years. It comes up with seven main findings, but the most interesting thing for me (given my work on badges) is the following:

If the authors are right, the way we signal ability (resumes listing education and work history) is not only a poor predictor of success, but has implications for existing companies, startups, education, and public policy that require further thought and research.It's perhaps a little simplistic as a binary, but Blank cites a 1970s paper that uses 'lemons' and 'cherries' as a metaphors to compare workers:

Lemons Versus Cherries. The most provocative conclusion in the paper is that asymmetric information about ability leads existing companies to employ only “lemons,” relatively unproductive workers. The talented and more productive choose entrepreneurship. (Asymmetric Information is when one party has more or better information than the other.) In this case the entrepreneurs know something potential employers don’t – that nowhere on their resume does it show resiliency, curiosity, agility, resourcefulness, pattern recognition, tenacity and having a passion for products.My main takeaway from this isn’t necessarily that entrepreneurship is always the best option, but that we’re really bad at signalling abilities and finding the right people to work with. I’m convinced that using digital credentials can improve that, but only if we use them in transformational ways, rather than replicate the status quo.This implication, that entrepreneurs are, in fact, “cherries” contrasts with a large body of literature in social science, which says that the entrepreneurs are the “lemons”— those who cannot find, cannot hold, or cannot stand “real jobs.”

Source: Steve Blank

Silicon Valley looking to skills from the Humanities

Cathy Davidson writing about the subjects that teach the kinds of skills that employers are really looking for:

Google’s studies concur with others trying to understand the secret of a great future employee. A recent survey of 260 employers by the nonprofit National Association of Colleges and Employers, which includes both small firms and behemoths like Chevron and IBM, also ranks communication skills in the top three most-sought after qualities by job recruiters. They prize both an ability to communicate with one’s workers and an aptitude for conveying the company’s product and mission outside the organization. Or take billionaire venture capitalist and “Shark Tank” TV personality Mark Cuban: He looks for philosophy majors when he’s investing in sharks most likely to succeed.Source: The Washington Post