- A New York School District Will Test Facial Recognition System On Students Even Though The State Asked It To Wait (BuzzFeed News) — "Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has expressed concern in a congressional hearing on the technology last week that facial recognition could be used as a form of social control."

- Amazon preparing a wearable that ‘reads human emotions,’ says report (The Verge) — "This is definitely one of those things that hasn’t yet been done because of how hard it is to do."

- Google’s Sundar Pichai: Privacy Should Not Be a Luxury Good (The New York Times) — "Ideally, privacy legislation would require all businesses to accept responsibility for the impact of their data processing in a way that creates consistent and universal protections for individuals and society as a whole.

- More workers want to slow down to get things right — "In reality, 61% of workers said they wanted to “slow down to get things right” while only 41%* wanted to “go fast to achieve more.” The divide was even starker among older workers."

- Workers strongly value uninterrupted focus at work, but most will make an exception to help others — "The results suggest we need to be more thoughtful about when we break our concentration, or ask others to do so. When people know they are helping others in a meaningful way, they tend to be okay with some distraction. But the busywork of meetings, alerts, and emails can quickly disrupt a person’s flow—one of the most important values we polled."

- Most workers have slightly more trust in people closest to the work, rather than people in upper management — "Among all respondents, 53% trusted people “closest to the work,” while only 45% trusted “upper management.” You might assume that younger workers would be the most likely to trust peers over management, but in fact, the opposite was true."

- Workers are torn between idealism and pragmatism — "It’s tempting to assume that addressing just one piece—like taking a stand on societal issues—will necessarily get in the way of the work itself. But our research suggests we can begin to solve the two in tandem, as more equality, inclusion, and diversity tends to come hand-in-hand with a healthier mindset about work."

- Health effects of job insecurity (IZA) — "Workers’ health is not just a matter for employees and employers, but also for public policy. Governments should count the health cost of restrictive policies that generate unemployment and insecurity, while promoting employability through skills training."

- Will your organization change itself to death? (opensource.com) — "Sometimes, an organization returns to the same state after sensing a stimulus. Think about a kid's balancing doll: You can push it and it'll wobble around, but it always returns to its upright state... Resilient organizations undergo change, but they do so in the service of maintaining equilibrium."

- Your Brain Can Only Take So Much Focus (HBR) — "The problem is that excessive focus exhausts the focus circuits in your brain. It can drain your energy and make you lose self-control. This energy drain can also make you more impulsive and less helpful. As a result, decisions are poorly thought-out, and you become less collaborative."

The end of the Millennial Lifestyle Subsidy

What goes up must come down. In this case with prices of services backed by VC firms, the reverse is true…

Source: Farewell, Millennial Lifestyle Subsidy | The New York TimesFor years, these subsidies allowed us to live Balenciaga lifestyles on Banana Republic budgets. Collectively, we took millions of cheap Uber and Lyft rides, shuttling ourselves around like bourgeois royalty while splitting the bill with those companies’ investors. We plunged MoviePass into bankruptcy by taking advantage of its $9.95-a-month, all-you-can-watch movie ticket deal, and took so many subsidized spin classes that ClassPass was forced to cancel its $99-a-month unlimited plan. We filled graveyards with the carcasses of food delivery start-ups — Maple, Sprig, SpoonRocket, Munchery — just by accepting their offers of underpriced gourmet meals.

These companies’ investors didn’t set out to bankroll our decadence. They were just trying to get traction for their start-ups, all of which needed to attract customers quickly to establish a dominant market position, elbow out competitors and justify their soaring valuations. So they flooded these companies with cash, which often got passed on to users in the form of artificially low prices and generous incentives.

Now, users are noticing that for the first time — whether because of disappearing subsidies or merely an end-of-pandemic demand surge — their luxury habits actually carry luxury price tags.

Hiring is broken, but not in the ways you assume

Hacker News is a link aggregator for people who work in tech. There's a lot of very technical information on there, but also stuff interesting to the curious mind more generally.

As so many people visit the site every day, it can be very influential, especially given the threaded discussion about shared links.

There can be a bit of a 'hive mind' sometimes, with certain things being sacred cows or implicit assumptions held by those who post (and lurk) there.

In this blog post focusing on hiring practices there's a critique of four 'myths' that seem to be prevalent in Hacker News discussions. Some of it is almost exclusively focused on tech roles in Silicon Valley, but I wanted to pull out this nugget which outlines what is really wrong with hiring:

Diversity. We really, really suck at diversity. We’re getting better, but we have a long way to go. Most of the industry chases the same candidates and assesses them in the same way.

Generally unfair practices. In cases where companies have power and candidates don’t, things can get really unfair. Lack of diversity is just one side-effect of this, others include poor candidate experiences, unfair compensation, and many others.

Short-termism. Recruiters and hiring managers that just want to fill a role at any cost, without thinking about whether there really is a fit or not. Many recruiters work on contingency, and most of them suck. The really good ones are awesome, but most of the well is poison. Hiring managers can be the same, too, when they’re under pressure to hire.

General ineptitude. Sometimes companies don’t knowing what they’re looking for, or are not internally aligned on it. Sometimes they just have broken processes, where they can’t keep track of who they’re talking to and what stage they’re at. Sometimes the engineers doing the interviews couldn’t care two shits about the interview or the company they work at. And often, companies are just tremendously indecisive, which makes them really slow to decide, or to just reject candidates because they can’t make up their minds.

Ozzie, 4 Hiring Myths Common in HackerNews Discussions

I've hired people and, even with the lastest talent management workflow software, it's not easy. It sucks up your time, and anything/everything you do can and will be criticised.

But that doesn't mean that we can't strive to make the whole process better, more equitable, and more enjoyable for all involved.

Ethics is the result of the human will

Sabelo Mhlambi is a computer scientist, researcher and Fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. He focuses on the ethical implications of technology in the developing world, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, and has written a great, concise essay on technological ethics in relation to the global north and south.

Ethics is not missing in technology, rather we are witnessing the ethics in technology – the ethics of the powerful. The ethics of individualism.

Mhlambi makes a number of important points, and I want to share three of them. First, he says that ethics is the result of human will, not algorithmic processes:

Ethics should not be left to algorithmic definitions and processes, ultimately ethics is a result of the human will. Technology won’t save us. The abdication of social and environmental responsibility by creators of technology should not be allowed to become the norm.

Second, technology is a driver of change in society, and, because technology is not neutral, we have individualism baked into the tools we use:

Ethics describes one’s relationship and responsibilities to others and the environment. Ethics is the protocol for human interaction, with each other and with the world. Different ethical systems may be described through this scale: Individualistic systems promote one’s self assertion through the limitation of one’s relationship and responsibilities to others and the environment. In contrast, a more communal ethics asserts the self through the encouragement of one’s relationship and responsibilities to the community and the environment.

This is, he says, a form of colonialism:

Technology designed and deployed beyond its ethical borders poses a threat to social stability in different regions with different ethical systems, norms and values. The imposition of a society’s beliefs on another is colonial. This relationship can be observed even amongst members of the South as the more economically developed nations extend their technology and influence into less developed nations, the East to Africa relationship being an example.

Third, over and above the individualism and colonialism, the technologies we use are unrepresentative because they do not take into account the lived experiences and view of marginalised groups:

In the development and funding of technology, marginalized groups are underrepresented. Their values and views are unaccounted for. In the software industry marginalized groups make a minority of the labor force and leadership roles. The digital divide continues to increase when technology is only accessible through the languages of the well developed nations.

It's an important essay, and one that I'll no doubt be returning to in the weeks and months to come.

Wretched is a mind anxious about the future

So said one of my favourite non-fiction authors, the 16th century proto-blogger Michel de Montaigne. There's plenty of writing about how we need to be anxious because of the drift towards a future of surveillance states. Eventually, because it's not currently affecting us here and now, we become blasé. We forget that it's already the lived experience for hundreds of millions of people.

Take China, for example. In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson writes about the Chinese government's brutality against the Muslim Uyghur population in the western province of Xinjiang:

[The] horrifying situation is built on the scaffolding of mass surveillance. Cameras fill the marketplaces and intersections of the key city of Kashgar. Recording devices are placed in homes and even in bathrooms. Checkpoints that limit the movement of Muslims are often outfitted with facial-recognition devices to vacuum up the population’s biometric data. As China seeks to export its suite of surveillance tech around the world, Xinjiang is a kind of R&D incubator, with the local Muslim population serving as guinea pigs in a laboratory for the deprivation of human rights.

Derek Thompson

As Ian Welsh points out, surveillance states usually involve us in the West pointing towards places like China and shaking our heads. However, if you step back a moment and remember that societies like the US and UK are becoming more unequal over time, then perhaps we're the ones who should be worried:

The endgame, as I’ve been pointing out for years, is a society in which where you are and what you’re doing, and have done is, always known, or at least knowable. And that information is known forever, so the moment someone with power wants to take you out, they can go back thru your life in minute detail. If laws or norms change so that what was OK 10 or 30 years ago isn’t OK now, well they can get you on that.

Ian Welsh

As the world becomes more unequal, the position of elites becomes more perilous, hence Silicon Valley billionaires preparing boltholes in New Zealand. Ironically, they're looking for places where they can't be found, while making serious money from providing surveillance technology. Instead of solving the inequality, they attempt to insulate themselves from the effect of that inequality.

A lot of the crazy amounts of money earned in Silicon Valley comes at the price of infringing our privacy. I've spent a long time thinking about quite nebulous concept. It's not the easiest thing to understand when you examine it more closely.

Privacy is usually considered a freedom from rather than a freedom to, as in "freedom from surveillance". The trouble is that there are many kinds of surveillance, and some of these we actively encourage. A quick example: I know of at least one family that share their location with one another all of the time. At the same time, of course, they're sharing it with the company that provides that service.

There's a lot of power in the 'default' privacy settings devices and applications come with. People tend to go with whatever comes as standard. Sidney Fussell writes in The Atlantic that:

Many apps and products are initially set up to be public: Instagram accounts are open to everyone until you lock them... Even when companies announce convenient shortcuts for enhancing security, their products can never become truly private. Strangers may not be able to see your selfies, but you have no way to untether yourself from the larger ad-targeting ecosystem.

Sidney Fussell

Some of us (including me) are willing to trade some of that privacy for more personalised services that somehow make our lives easier. The tricky thing is when it comes to employers and state surveillance. In these cases there are coercive power relationships at play, rather than just convenience.

Ellen Sheng, writing for CNBC explains how employees in the US are at huge risk from workplace surveillance:

In the workplace, almost any consumer privacy law can be waived. Even if companies give employees a choice about whether or not they want to participate, it’s not hard to force employees to agree. That is, unless lawmakers introduce laws that explicitly state a company can’t make workers agree to a technology...

One example: Companies are increasingly interested in employee social media posts out of concern that employee posts could reflect poorly on the company. A teacher’s aide in Michigan was suspended in 2012 after refusing to share her Facebook page with the school’s superintendent following complaints about a photo she had posted. Since then, dozens of similar cases prompted lawmakers to take action. More than 16 states have passed social media protections for individuals.

Ellen Sheng

It's not just workplaces, though. Schools are hotbeds for new surveillance technologies, as Benjamin Herold notes in an article for Education Week:

Social media monitoring companies track the posts of everyone in the areas surrounding schools, including adults. Other companies scan the private digital content of millions of students using district-issued computers and accounts. Those services are complemented with tip-reporting apps, facial-recognition software, and other new technology systems.

[...]

While schools are typically quiet about their monitoring of public social media posts, they generally disclose to students and parents when digital content created on district-issued devices and accounts will be monitored. Such surveillance is typically done in accordance with schools’ responsible-use policies, which students and parents must agree to in order to use districts’ devices, networks, and accounts.

Benjamin Herold

Hypothetically, students and families can opt out of using that technology. But doing so would make participating in the educational life of most schools exceedingly difficult.

In China, of course, a social credit system makes all of this a million times worse, but we in the West aren't heading in a great direction either.

We're entering a time where, by the time my children are my age, companies, employers, and the state could have decades of data from when they entered the school system through to them finding jobs, and becoming parents themselves.

There are upsides to all of this data, obviously. But I think that in the midst of privacy-focused conversations about Amazon's smart speakers and Google location-sharing, we might be missing the bigger picture around surveillance by educational institutions, employers, and governments.

Returning to Ian Welsh to finish up, remember that it's the coercive power relationships that make surveillance a bad thing:

Surveillance societies are sterile societies. Everyone does what they’re supposed to do all the time, and because we become what we do, it affects our personalities. It particularly affects our creativity, and is a large part of why Communist surveillance societies were less creative than the West, particularly as their police states ramped up.

Ian Welsh

We don't want to think about all of this, though, do we?

Also check out:

Everyone hustles his life along, and is troubled by a longing for the future and weariness of the present

Thanks to Seneca for today's quotation, taken from his still-all-too-relevant On the Shortness of Life. We're constantly being told that we need to 'hustle' to make it in today's society. However, as Dan Lyons points out in a book I'm currently reading called Lab Rats: how Silicon Valley made work miserable for the rest of us, we're actually being 'immiserated' for the benefit of Venture Capitalists.

As anyone who's read Daniel Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow will know, there are two dominant types of thinking:

The central thesis is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. The book delineates cognitive biases associated with each type of thinking, starting with Kahneman's own research on loss aversion. From framing choices to people's tendency to replace a difficult question with one which is easy to answer, the book highlights several decades of academic research to suggest that people place too much confidence in human judgement.

WIkipedia

Cal Newport, in a book of the same name, calls 'System 2' something else: Deep Work. Seneca, Kahneman, and Newport, are all basically saying the same thing but with different emphasis. We need to allow ourselves time for the slower and deliberative work that makes us uniquely human.

That kind of work doesn't happen when you're being constantly interrupted, nor when you're in an environment that isn't comfortable, nor when you're fearful that your job may not exist next week. A post for the Nuclino blog entitled Slack Is Not Where 'Deep Work' Happens uses a potentially-apocryphal tale to illustrate the point:

On one morning in 1797, the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was composing his famous poem Kubla Khan, which came to him in an opium-induced dream the night before. Upon waking, he set about writing until he was interrupted by an unknown person from Porlock. The interruption caused him to forget the rest of the lines, and Kubla Khan, only 54 lines long, was never completed.

Nuclino blog

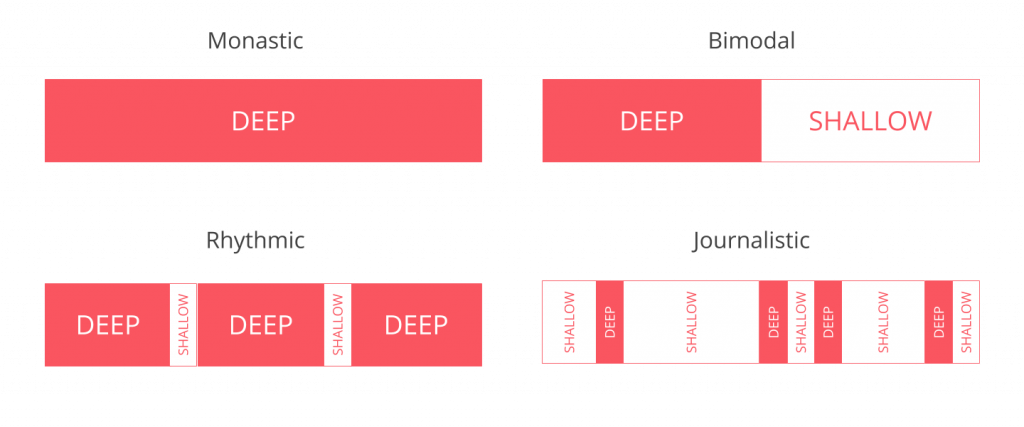

What we're actually doing by forcing everyone to use synchronous tools like Slack is a form of journalistic rhythm — but without everyone being synced-up:

If you haven't read Deep Work, never fear, because there's an epic article by Fadeke Adegbuyi for doist entitled The Complete Guide to Deep Work which is particularly useful:

This is an actionable guide based directly on Newport’s strategies in Deep Work. While we fully recommend reading the book in its entirety, this guide distills all of the research and recommendations into a single actionable resource that you can reference again and again as you build your deep work practice. You’ll learn how to integrate deep work into your life in order to execute at a higher level and discover the rewards that come with regularly losing yourself in meaningful work.

Fadeke Adegbuyi

Lots of articles and podcast episodes say they're 'actionable' or provide 'tactics' for success. I have to say this one delivers. I'd still read Newport's book, though.

Interestingly, despite all of the ridiculousness spouted by VC's, people are pretty clear about how they can do their best work. After a Dropbox survey of 500 US-based workers in the knowledge economy, Ben Taylor outlines four 'lessons' they've learned:

I think we need to reclaim workplace culture from the hustlers, shallow thinkers, and those focused on short-term profit. Let's reflect on how things actually work in practice. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb says about being 'antifragile', let's "look for habits and rules that have been around for a long time".

Also check out:

Charisma instead of hierarchy?

An interesting interview with Fred Turner, former journalist, Stanford professor, and someone who spends a lot of time studying the technology and culture of Silicon Valley.

Turner likens tech companies who try to do away with hierarchy to 1960s communes:

When you take away bureaucracy and hierarchy and politics, you take away the ability to negotiate the distribution of resources on explicit terms. And you replace it with charisma, with cool, with shared but unspoken perceptions of power. You replace it with the cultural forces that guide our behavior in the absence of rules.It's an interesting viewpoint, and one which chimes with works such as The Tyranny of Structurelessness. I still think less hierarchy is a good thing. But then I would say that, because I'm a white, privileged western man getting ever-closer to middle-age...

Source: Logic magazine

What would a version of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs for society look like?

I like the notion put forward by Susan Wu in this article — although Maslow’s framework was actually based on co-operation, so re-thinking it as a dynamic hierarchy may be all that’s required:

Perhaps it's time for an updated version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, one that underscores what’s essential not just for individuals to flourish, but for the greater good of society. Startups and management executives universally invoke this theory as an accepted canon for framing the human problems they’re trying to solve.Source: WIREDThe problem is that Maslow’s framework pertains to individual, not societal, well-being. The reality is that individual needs cannot be met without the social cohesion of belonging, connectedness, and symbiotic networks. A revised design focused on a thriving civilization would have at its root empathy and ethics, and acknowledge that if inequality continues to grow at its current pace, societal well-being becomes impossible to achieve.