- Are we on the road to civilisation collapse? (BBC Future) — "Collapse is often quick and greatness provides no immunity. The Roman Empire covered 4.4 million sq km (1.9 million sq miles) in 390. Five years later, it had plummeted to 2 million sq km (770,000 sq miles). By 476, the empire’s reach was zero."

- Fish farming could be the center of a future food system (Fast Company) — "Aquaculture has been shown to have 10% of the greenhouse gas emissions of beef when it’s done well, and 50% of the feed usage per unit of production as beef"

- The global internet is disintegrating. What comes next? (BBC FutureNow) — "A separate internet for some, Facebook-mediated sovereignty for others: whether the information borders are drawn up by individual countries, coalitions, or global internet platforms, one thing is clear – the open internet that its early creators dreamed of is already gone."

- More workers want to slow down to get things right — "In reality, 61% of workers said they wanted to “slow down to get things right” while only 41%* wanted to “go fast to achieve more.” The divide was even starker among older workers."

- Workers strongly value uninterrupted focus at work, but most will make an exception to help others — "The results suggest we need to be more thoughtful about when we break our concentration, or ask others to do so. When people know they are helping others in a meaningful way, they tend to be okay with some distraction. But the busywork of meetings, alerts, and emails can quickly disrupt a person’s flow—one of the most important values we polled."

- Most workers have slightly more trust in people closest to the work, rather than people in upper management — "Among all respondents, 53% trusted people “closest to the work,” while only 45% trusted “upper management.” You might assume that younger workers would be the most likely to trust peers over management, but in fact, the opposite was true."

- Workers are torn between idealism and pragmatism — "It’s tempting to assume that addressing just one piece—like taking a stand on societal issues—will necessarily get in the way of the work itself. But our research suggests we can begin to solve the two in tandem, as more equality, inclusion, and diversity tends to come hand-in-hand with a healthier mindset about work."

- Health effects of job insecurity (IZA) — "Workers’ health is not just a matter for employees and employers, but also for public policy. Governments should count the health cost of restrictive policies that generate unemployment and insecurity, while promoting employability through skills training."

- Will your organization change itself to death? (opensource.com) — "Sometimes, an organization returns to the same state after sensing a stimulus. Think about a kid's balancing doll: You can push it and it'll wobble around, but it always returns to its upright state... Resilient organizations undergo change, but they do so in the service of maintaining equilibrium."

- Your Brain Can Only Take So Much Focus (HBR) — "The problem is that excessive focus exhausts the focus circuits in your brain. It can drain your energy and make you lose self-control. This energy drain can also make you more impulsive and less helpful. As a result, decisions are poorly thought-out, and you become less collaborative."

What if I never change?

Oliver Burkeman on Jocelyn K. Glei’s Hurrry Slowly is an absolute treat. In particular, he quotes Jim Benson on how we can easily become “a limitless reservoir for other people’s expectations”. I also liked the discussion around the “internalised capitalism” of “clock time”.

The title comes from an important point that Burkeman makes about so many of our hopes and dreams being based on somehow in the future being a radically different person to who we are now.

It reminded me of a section in Alain de Botton’s The Art of Travel in which he summarises Seneca by saying that the problem about going somewhere to escape things is that you always take yourself (and your mental/emotional baggage) with you…

Oliver Burkeman on why we try to control time, how perfectionism holds us back, and the problems with a “when-i-finally” mindset.Source: Oliver Burkeman: What if I never change? | Hurry Slowly

Thus each man ever flees himself

There are some days during this current pandemic when, coccooned in my little bubble, I can forget for a few hours that the world has changed. Conversely, I encounter other days when my baseline existential angst spikes to a level just below "rocking backwards-and-forwards in the corner of the room".

There are a range of ways for obtaining help in such situations, including professional (therapy!), spiritual (religion!) and medical (drugs!) However, while I've dabbled with all three, perhaps my greatest solace comes from bunch of balding white dudes who lived a couple of thousand years ago.

Yes, I'm talking about the Stoics. Having re-read the Seneca's On the Tranquility of the Mind this week, I thought there were whole sections worth sharing for anyone in a similar predicament to me.

In this dialogue, Serenus explains to Seneca his problem. The details may have changed over the years (no slaves, and we tend not to be so envious about other people's crockery) but the gist is, at least for me, immediately recognisable:

The nature of this mental weakness which hovers between two alternatives, inclining strongly neither to the right nor to the wrong, I can better show you one part at a time than all at once; I will tell you my experience, you will find a name for my sickness. I am completely devoted, I admit, to frugality: I do not like a couch made up for show, or clothing produced from a chest or pressed by weights and a thousand mangles to make it shiny, but rather something homely and inexpensive that has not been kept specially or needs to be put on with anxious care; I like food that a household of slaves has not pr pared, watching it with envy, that has not been ordered many days in advance or served up by many hands, but is easy to fetch and in ample supply; it has nothing outlandish or expensive about it, and will be readily available everywhere, it will not put a strain on one’s purse or body, or return by the way it entered; I like for my servant a young house-bred slave without training or polish, for silverware my country-bred father’s heavy plate that bears no maker’s stamp, and for a table one that is not remarkable for the variety of its markings or known to Rome for having passed through the hands of many stylish owners, but one that is there to be used, that makes no guest stare at it in endless pleasure or burning envy. Then, after finding perfect satisfaction in all such things, I find my mind is dazzled by the splendour of some training-school for pages, by the sight of slaves decked out in gold and more scrupulously dressed than bearers in a procession, and a whole troop of brilliant attendants; by the sight of a house where even the floor one treads is precious and riches are strewn in every corner, where the roofs themselves shine out, and the citizen body waits in attendance and dutifully accompanies an inheritance whose days are numbered; need I mention the waters, transparent to the bottom and flowing round the guests even as they dine, or the banquets that in no way disgrace their setting? Emerging from a long time of dedication to thrift, luxury has enveloped me in the riches of its splendour, filling my ears with all its sounds: my vision falters a little, for it is easier for me to raise my mind to it than my eyes; and so I come back, not a worse man, but a sadder one, I no longer walk with head so high among those worthless possessions of mine, and I feel the sharpness of a secret pain as the doubt arises whether that life is not the better one. None of these things alters me, but none fails to unsettle me.

'Serenus' (in Seneca's 'On The Tranquility of the Mind')

As a result, Serenus asks Seneca for help, as he feels stuck between two stools: asceticism and luxury:

I ask you, therefore, if you possess any cure by which you can check this fluctuation of mine, to consider me worthy of being indebted to you for tranquillity. I am aware that these mental disturbances I suffer from are not dangerous and bring no threat of a storm; to express to you in a true analogy the source of my complaint, it is not a storm I labour under but seasickness: relieve me, then, of this malady, whatever it be, and hurry to aid one who struggles with land in his sight.

'Serenus' (in seneca's 'On The Tranquility of the Mind')

For me, Serenus' description of his 'mental disturbances' as being like seasickness really resonate with me. As a friend said earlier this week, we're both a little tired of the "constant up and down".

Seneca restates Serenus' problem, first stating what he doesn't require:

Accordingly, you have no need of those harsher measures that we have already passed over, that of sometimes opposing yourself, of sometimes getting angry with yourself, of sometimes fiercely driving yourself on, but rather of the one that comes last, having confidence in yourself and believing that you are on the right path and have not been sidetracked by the footprints crossing over, left by many rushing in different directions, some of them wandering close to the path itself.

seneca, 'On The Tranquility of the Mind'

Another useful metaphor, of being sidetracked by other people's, and perhaps your own, footprints. Instead what Seneca explains that Serenus needs to have "confidence" in himself, and believe that he is "on the right path".

Don't we all need that?

Seneca continues by saying that everyone is in the same boat, which might as well be named The Human Condition. What he diagnoses as the nub of the problem, which is think is particularly insightful, is our attempts to keep changing things. Ultimately, this simply means we live in a constant state of suspense and dissatisfaction.

Everyone is in the same predicament, both those who are tormented by inconstancy and boredom and an unending change of purpose, constantly taking more pleasure in what they have just abandoned, and those who idle away their time, yawning. Add to them those who twist and turn like insomniacs, trying all manner of positions until in their weariness they find repose: by altering the condition of their life repeatedly, they end up finally in the state that they are caught, not by dislike of change, but by old age that is reluctant to embrace anything new. Add also those who through the fault, not of determination but of idleness, are too constant in their ways, and live their lives not as they wish, but as they began. The sickness has countless characteristics but only one effect, dissatisfaction with oneself. This arises from a lack of mental balance and desires that are nervous or unfulfilled, when men’s daring or attainment falls short of their desires and they depend entirely on hope; such are always lacking in stability and changeable, the inevitable consequence of living in a state of suspense.

seneca, 'On The Tranquility of the Mind'

Next, Seneca seemingly reaches through the ages to drive his point home with sentences which, despite being aimed at his interlocutor, seem targeted at me.

All these feelings are aggravated when disgust at the effort they have spent on becoming unsuccessful drives men to leisure, to solitary studies, which are unendurable for a mind intent on a public career, eager for employment, and by nature restless, since without doubt it possesses few enough resources for consolation; for this reason, once it has been deprived of those delights that business itself affords to active participants, the mind does not tolerate home, solitude, or the walls of a room, and does not enjoy seeing that it has been left to itself. This is the source of that boredom and dissatisfaction, of the wavering of a mind that finds no rest anywhere, and the sad and spiritless endurance of one’s leisure; and particularly when one is ashamed to confess the reasons for these feelings, and diffidence drives its torments inwards, the desires, confined in a narrow space from which there is no escape, choke one-another; hence come grief and melancholy and the thousand fluctuations of an uncertain mind, held in suspense by early hopes and then reduced to sadness once they fail to materialize; this causes that feeling which makes men loathe their own leisure and complain that they themselves have nothing to keep them occupied, and also the bitterest feelings of jealousy of other men’s successes.

Seneca, 'On The Tranquility of the Mind'

Seneca continues to give Serenus more advice in the dialogue, but, every time I read these opening few pages, I feel like he has diagnosed not only my condition, and that of all humankind.

While some people are always on the lookout for the new and the novel, I'm realising that the best way to spend the second half of my life might well be to spend a good amount of time wringing out as much value from things I've already discovered.

The quotations in this post are from the Oxford World's Classics version of Seneca's Dialogues and Essays. If you can't find it in your local library, try here.

If you're new to the Stoics, may I suggest starting with The Enchiridion by Epictetus? I'd follow that with Marcus Aurelius' Meditations (buy a decent quality dead-tree version; you'll thank me in years to come) and then dip into Seneca's somewhat voluminous works.

Header image by Simon Migaj. Quotation-as-title from Lucretius, who Seneca quotes in 'On the Tranquility of the Mind'.

It is the child within us that trembles before death

So said Plato in his Phaedo. I've just returned from a holiday, much of which was dominated by finding out that a good friend of mine had passed away. It was a huge shock.

A few days later, author Austin Kleon sent out a newsletter noting that a few people he particularly admired had also died, and linked to a post about checking in with death. In it, he quotes advice from a pediatrician who works with patients in palliative care:

Be kind. Read more books. Spend time with your family. Crack jokes. Go to the beach. Hug your dog. Tell that special person you love them.

These are the things these kids wished they could’ve done more. The rest is details.

Oh… and eat ice-cream.

Alastair McAlpine

Despite my grandmother dying last year, I was utterly unprepared for the death of my friend. I had thought that by reading Stoic philosophy every day, and having a memento mori next to my bed, that I was somehow in tune with death. I really wasn't.

I shed many tears for the first couple of days after hearing the news. While I was devastated by the loss of a good friend, I was also affected by the questions it raised about my own mortality.

I'm thankful for the strong support network of family and friends that have helped me with the grieving process. One friend in particular has a much healthier relationship with death than me. They said that they've come to see such times in their life as a useful opportunity to re-assess whether they're on the right course.

That makes sense. I don't want to waste the rest of the time I have left.

Some have no aims at all for their life’s course, but death takes them unawares as they yawn languidly – so much so that I cannot doubt the truth of that oracular remark of the greatest of poets: ‘It is a small part of life we really live.’ Indeed, all the rest is not life but merely time.

Seneca

Some people seem to pack several lifetimes into their short time on earth. Others, not so much.

When I studied Philosophy as an undergraduate, I was always puzzled by Aristotle's mention of Solon in the Nichomachean Ethics. He thought events and actions after a person's death could affect their 'happiness'.

On reflection, I think it's a way of saying that the effect that someone has during their time on earth — for example, as a teacher — outlasts them. Their lives can be viewed in a 'happy' or 'unhappy' light based on how things turn out.

When someone close to you dies before they reach old age, we also mentally factor-in the happiness they could have experienced after they passed away. However, after the initial shock of them no longer being present comes the realisation that they (and you) wouldn't have been around forever anyway.

Back in 2017, Zan Boag, editor of New Philosopher magazine, interviewed Hilde Lindemann, Professor of Philosophy at Michigan State University. In a wide-ranging interview, she commented:

Premature death is a tragedy, but I don’t think death at the end of a normal human life span should be met with anger and indignation. We humans can only take in so much, and in due season it will be time for us all to leave

Hilde Lindemann

As a husband and father, perhaps the hardest teaching from the Stoic philosophers around death comes from Epictetus in his Enchiridion. He expresses a similar thought in several different ways, but here is one formulation:

If you wish your children, and your wife, and your friends to live for ever, you are stupid; for you wish to be in control of things which you cannot, you wish for things that belong to others to be your own... Exercise, therefore, what is in your control.

Epictetus

There are some things that are in my control, and some things that are not. Epictetus' teachings can be reduced to the simple point that we should be concerned with those things which are under our control.

Marcus Aurelius, whose Meditations we should remember were designed as a form of practical philosophical journal, also mentioned death a lot.

Do not act as if you had ten thousand years to throw away. Death stands at your elbow. Be good for something while you live and it is in your power.

Marcus Aurelius

I think the best thing to take from the experience of losing someone close to us other is to begin a life worth living right now. Not putting off for the future right action and virtuous living, but practising them immediately.

It's certainly been a wake-up call for me. I'll be reading even more books, giving my family more hugs, and standing up for the things in which I believe. Starting now.

Aren’t you ashamed to reserve for yourself only the remnants of your life and to dedicate to wisdom only that time can’t be directed to business?

Once you remove the specific details from the lives of the ancients, their lives were remarkably like ours. Take today's title, for example, which is a quotation from Seneca. He knew what it was like to be so busy doing 'productive' things to the exclusion of almost everything else.

My good friend Laura Hilliger wears her heart on her sleeve, and is the most no-nonsense person I know. By observing the way she lives and works, I'm learning to set limits and say exactly what I think:

The thing is that western society, implicitly at least, assumes that people are 'fixed' in terms of their personality and likes. But that's just the way that we choose to see ourselves:

I feel that the biggest thing that constrains us is our view of how we think other people see us. That perceived expectation becomes internalised, creating a 'psychic prison' which becomes an extremely limited playground. For better or for worse, we perform the role of how we think other people have come to see us.

One way many people find to avoid responsibility for their life choices is to play the 'busy' card. They're too busy to make good decisions, to look after their mental and physical health, to ensure that they're doing your best work.

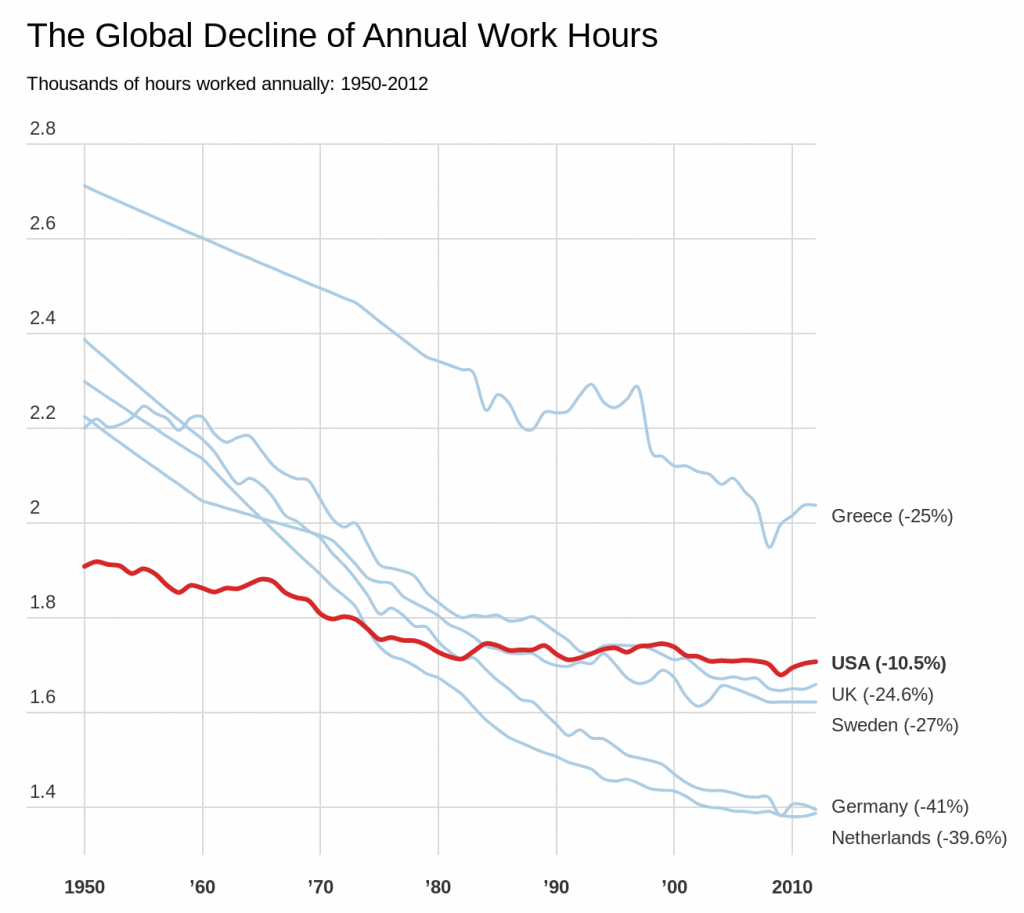

The trouble is, that's simply not true. We've got more free time than our parents and grandparents:

As the above chart demonstrates, it's not true that we actually work more hours. Instead, I think, it's that we're so concerned about how other people see us that we spend time doing things that feel like work but are mostly to do with presentation of self. Hence the amount of time spent on social networks like Instagram trying to create the highlights reel of our lives to show others.

One way of viewing this is that we've collectively internalised capitalism. The logic of the market has become as invisible to us as an ideology as water is to fish. In fact, some people say it's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism!

Of course, it's become something of a cliché in our pseudo-enlightened times to talk of capitalism as the meta-problem behind everything. But that doesn't make it any less true.

Our identity is mediated by the market, by what we produce instead of who we are. I keep coming back to a fantastic episode of Jocelyn K. Glei's Hurry Slowly podcast entitled Who Are You Without The Doing? in which she explains that we should learn to 'sit with ourselves', learning that change comes from within:

You have to completely conquer the feeling that there is something fundamentally wrong with your human nature, and that therefore you need discipline to correct your behavior. As long as you feel the discipline comes from the outside, there is still a feeling that something is lacking in you.

Jocelyn K. Glei

Derek Sivers uses the metaphor of 'doors' to explain where he finds value and wants to spend time doing. Some doors he opens and it helps him grow as a person and fosters positive relationships.

But one door is really no fun to open. I’m horrified at all the shouting, the second I open it. It’s an infinite dark room filled with psychologically tortured people, trying to get attention. Strangers screaming at strangers, starting fights. Businesses set up shop there, showing who’s said and done bad things today, because they make money when people get mad.

Derek Sivers

We keep wringing our hands about people's behaviour online, but it's that way for a reason. Hate is profitable for social networks:

Massive platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube “optimize for engagement,” and make automatic, algorithmic suggestions for every bit of content or action. From “you might also like” to “recommended just for you” to prioritizing things — anything — that will get you to click, comment, or share.

[...]

They know what will catch your attention. They know what will get you “engaged.” They know what will be more likely to lead you deeper into a rabbit hole, and what will make it harder to climb back out. Is it a literal, iron-clad trap? No. But the slippery, spiral path that leads people to the darkest corners of the internet is not an accident.

[...]

Hate is profitable. Conflict is profitable. Schadenfreude and shame are profitable. While we smugly point fingers, tsk-tsk, and think we’re being clever as we strategically dole out likes and shares, we forget that we are all just gruel-fed hamsters running on wheels deep inside giant, hyper-engineered, artificially intelligent, fully gamified, corporate-controlled virtual worlds that we absurdly think belong to us.

Ryan Ozawa

This all comes back to the time equation. Because we feel like we don't have enough time to curate things ourselves, we outsource that to others. That ends up with handing our information environments over to others to manipulate and control. It's curate or be curated.

Nobody cares about how much money you earn. Nobody cares how productive you are. Not really.

Also, without sounding harsh, nobody else cares how productive you are. Of course, productivity is important for important things, and “getting stuff done” or whatever, but it doesn’t define you in any way. What does is things like your sense of humour, where your passions lie, how you comfort a friend who’s upset, and that weird noise you make when the delivery guy calls you to say he’s outside with your food.

Leila Mitwally

The trouble is that we don't want to have this conversation, because it questions our identity, and everything we've been working for over our careers and throughout our lives:

But we don’t want to hear that because accepting this truth means asking a lot of complicated questions about our society, in which work is glorified as the pinnacle of self-expression, and personal earnings are viewed as a measure of merit and esteem.

Instead, we would instead read about buy into the idea that success in our work life is a merely a matter of being more productive. If you just follow the ‘right’ set of algorithms or rules, you too can achieve ‘success’ in your work life, along with fame and recognition and a fat bank account.

Richard Whittall

So, to finish, let me revisit a link I shared recently from Jason Hickel. We can choose to live differently, to recognise the abundance of time and resources we have in the world. To slow down, to take stock, and reject economic growth as in any way a useful indicator of human flourishing:

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can call a halt to the madness – throw a wrench in the juggernaut. By de-enclosing social goods and restoring the commons, we can ensure that people are able to access the things that they need to live a good life without having to generate piles of income in order to do so, and without feeding the never-ending growth machine. “Private riches” may shrink, as Lauderdale pointed out, but public wealth will increase.

Jason Hickel

It doesn't have to be difficult. We can just, as Dan Lyons mentions in his book Lab Rats, decide to work on things that 'close the gap' or 'increase the gap'. What that means to you, in your context, is a different matter.

One can see only what one has already seen

Fernando Pessoa with today's quotation-as-title. He's best known for The Book of Disquiet which he called "a factless autobiography". It's... odd. Here's a sample:

Whether or not they exist, we're slaves to the gods.

Fernando pessoa

I've been reading a lot of Seneca recently, who famously said:

Life is divided into three periods, past, present and future. Of these, the present is short, the future is doubtful, the past is certain.

Seneca

The trouble is, we try and predict the future in order to control the future. Some people have a good track record in this, partly because they are involved in shaping things in the present. Other people have a vested interest in trying to get the world to bend to their ideology.

In an article for WIRED, Joi Ito, Director of the MIT Media Lab writes about 'extended intelligence' being the future rather than AI:

The notion of singularity – which includes the idea that AI will supercede humans with its exponential growth, making everything we humans have done and will do insignificant – is a religion created mostly by people who have designed and successfully deployed computation to solve problems previously considered impossibly complex for machines.

Joi Ito

It's a useful counter-balance to those banging the AI drum and talking about the coming jobs apocalypse.

After talking about 'S curves' and adaptive systems, Ito explains that:

Instead of thinking about machine intelligence in terms of humans vs machines, we should consider the system that integrates humans and machines – not artificial intelligence but extended intelligence. Instead of trying to control or design or even understand systems, it is more important to design systems that participate as responsible, aware and robust elements of even more complex systems.

Joi Ito

I haven't had a chance to read it yet, but I'm looking forward to seeing some of the ideas put forward in The Weight of Light: a collection of solar futures (which is free to download in multiple formats). We need to stop listening solely to rich white guys proclaiming the Silicon Valley narrative of 'disruption'. There are many other, much more collaborative and egalitarian, ways of thinking about and designing for the future.

This collection was inspired by a simple question: what would a world powered entirely by solar energy look like? In part, this question is about the materiality of solar energy—about where people will choose to put all the solar panels needed to power the global economy. It’s also about how people will rearrange their lives, values, relationships, markets, and politics around photovoltaic technologies. The political theorist and historian Timothy Mitchell argues that our current societies are carbon democracies, societies wrapped around the technologies, systems, and logics of oil.What will it be like, instead, to live in the photon societies of the future?

The Weight of Light: a collection of solar futures

We create the future, it doesn't just happen to us. My concern is that we don't recognise the signs that we're in the last days. Someone shared this quotation from the philosopher Kierkegaard recently, and I think it describes where we're at pretty well:

A fire broke out backstage in a theatre. The clown came out to warn the public; they thought it was a joke and applauded. He repeated it; the acclaim was even greater. I think that's just how the world will come to an end: to general applause from wits who believe it's a joke.

Søren Kierkegaard

Let's home we collectively wake up before it's too late.

Also check out:

Everyone hustles his life along, and is troubled by a longing for the future and weariness of the present

Thanks to Seneca for today's quotation, taken from his still-all-too-relevant On the Shortness of Life. We're constantly being told that we need to 'hustle' to make it in today's society. However, as Dan Lyons points out in a book I'm currently reading called Lab Rats: how Silicon Valley made work miserable for the rest of us, we're actually being 'immiserated' for the benefit of Venture Capitalists.

As anyone who's read Daniel Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow will know, there are two dominant types of thinking:

The central thesis is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. The book delineates cognitive biases associated with each type of thinking, starting with Kahneman's own research on loss aversion. From framing choices to people's tendency to replace a difficult question with one which is easy to answer, the book highlights several decades of academic research to suggest that people place too much confidence in human judgement.

WIkipedia

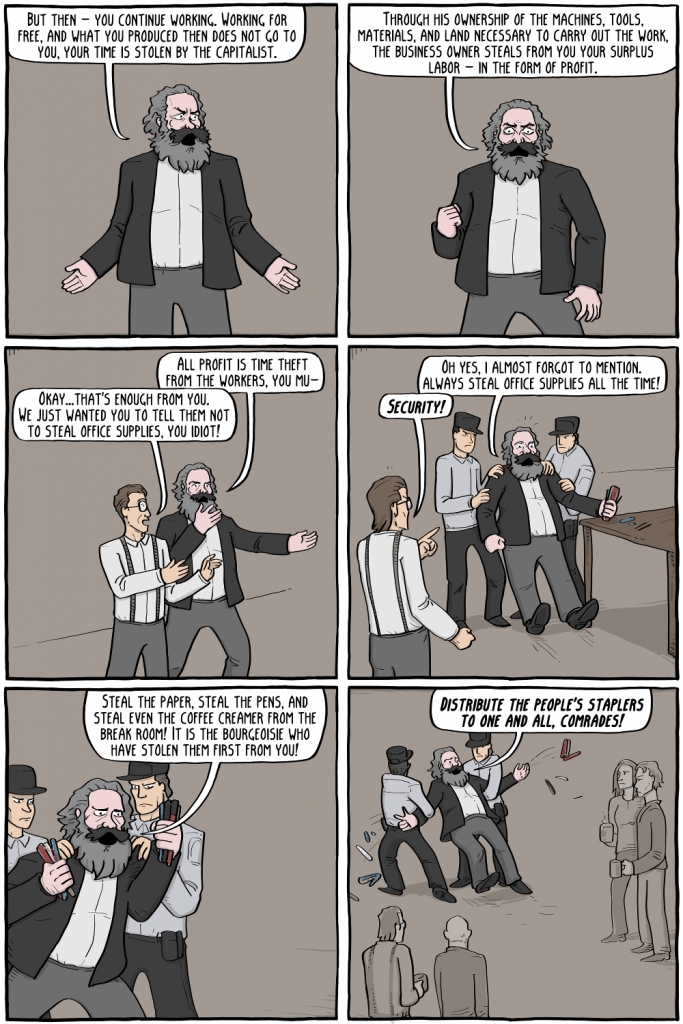

Cal Newport, in a book of the same name, calls 'System 2' something else: Deep Work. Seneca, Kahneman, and Newport, are all basically saying the same thing but with different emphasis. We need to allow ourselves time for the slower and deliberative work that makes us uniquely human.

That kind of work doesn't happen when you're being constantly interrupted, nor when you're in an environment that isn't comfortable, nor when you're fearful that your job may not exist next week. A post for the Nuclino blog entitled Slack Is Not Where 'Deep Work' Happens uses a potentially-apocryphal tale to illustrate the point:

On one morning in 1797, the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was composing his famous poem Kubla Khan, which came to him in an opium-induced dream the night before. Upon waking, he set about writing until he was interrupted by an unknown person from Porlock. The interruption caused him to forget the rest of the lines, and Kubla Khan, only 54 lines long, was never completed.

Nuclino blog

What we're actually doing by forcing everyone to use synchronous tools like Slack is a form of journalistic rhythm — but without everyone being synced-up:

If you haven't read Deep Work, never fear, because there's an epic article by Fadeke Adegbuyi for doist entitled The Complete Guide to Deep Work which is particularly useful:

This is an actionable guide based directly on Newport’s strategies in Deep Work. While we fully recommend reading the book in its entirety, this guide distills all of the research and recommendations into a single actionable resource that you can reference again and again as you build your deep work practice. You’ll learn how to integrate deep work into your life in order to execute at a higher level and discover the rewards that come with regularly losing yourself in meaningful work.

Fadeke Adegbuyi

Lots of articles and podcast episodes say they're 'actionable' or provide 'tactics' for success. I have to say this one delivers. I'd still read Newport's book, though.

Interestingly, despite all of the ridiculousness spouted by VC's, people are pretty clear about how they can do their best work. After a Dropbox survey of 500 US-based workers in the knowledge economy, Ben Taylor outlines four 'lessons' they've learned:

I think we need to reclaim workplace culture from the hustlers, shallow thinkers, and those focused on short-term profit. Let's reflect on how things actually work in practice. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb says about being 'antifragile', let's "look for habits and rules that have been around for a long time".

Also check out:

What we can learn from Seneca about dying well

As I’ve shared before, next to my bed at home I have a memento mori, an object to remind me before I go to sleep and when I get up that one day I will die. It kind of puts things in perspective.

“Study death always,” Seneca counseled his friend Lucilius, and he took his own advice. From what is likely his earliest work, the Consolation to Marcia (written around AD 40), to the magnum opus of his last years (63–65), the Moral Epistles, Seneca returned again and again to this theme. It crops up in the midst of unrelated discussions, as though never far from his mind; a ringing endorsement of rational suicide, for example, intrudes without warning into advice about keeping one’s temper, in On Anger. Examined together, Seneca’s thoughts organize themselves around a few key themes: the universality of death; its importance as life’s final and most defining rite of passage; its part in purely natural cycles and processes; and its ability to liberate us, by freeing souls from bodies or, in the case of suicide, to give us an escape from pain, from the degradation of enslavement, or from cruel kings and tyrants who might otherwise destroy our moral integrity.Seneca was forced to take his own life by his own pupil, the more-than-a-little-crazy Roman Emperor, Nero. However, his whole life had been a preparation for such an eventuality.

Seneca, like many leading Romans of his day, found that larger moral framework in Stoicism, a Greek school of thought that had been imported to Rome in the preceding century and had begun to flourish there. The Stoics taught their followers to seek an inner kingdom, the kingdom of the mind, where adherence to virtue and contemplation of nature could bring happiness even to an abused slave, an impoverished exile, or a prisoner on the rack. Wealth and position were regarded by the Stoics as adiaphora, “indifferents,” conducing neither to happiness nor to its opposite. Freedom and health were desirable only in that they allowed one to keep one’s thoughts and ethical choices in harmony with Logos, the divine Reason that, in the Stoic view, ruled the cosmos and gave rise to all true happiness. If freedom were destroyed by a tyrant or health were forever compromised, such that the promptings of Reason could no longer be obeyed, then death might be preferable to life, and suicide, or self-euthanasia, might be justified.Given that death is the last taboo in our society, it's an interesting way to live your life. Being ready at any time to die, having lived a life that you're satisfied with, seems like the right approach to me.

“Study death,” “rehearse for death,” “practice death”—this constant refrain in his writings did not, in Seneca’s eyes, spring from a morbid fixation but rather from a recognition of how much was at stake in navigating this essential, and final, rite of passage. As he wrote in On the Shortness of Life, “A whole lifetime is needed to learn how to live, and—perhaps you’ll find this more surprising—a whole lifetime is needed to learn how to die.”Source: Lapham's Quarterly