- We Have No Reason to Believe 5G Is Safe (Scientific American) — "The latest cellular technology, 5G, will employ millimeter waves for the first time in addition to microwaves that have been in use for older cellular technologies, 2G through 4G. Given limited reach, 5G will require cell antennas every 100 to 200 meters, exposing many people to millimeter wave radiation... [which are] absorbed within a few millimeters of human skin and in the surface layers of the cornea. Short-term exposure can have adverse physiological effects in the peripheral nervous system, the immune system and the cardiovascular system."

- Situated degree pathways (The Ed Techie) — "[T]he Trukese navigator “begins with an objective rather than a plan. He sets off toward the objective and responds to conditions as they arise in an ad hoc fashion. He utilizes information provided by the wind, the waves, the tide and current, the fauna, the stars, the clouds, the sound of the water on the side of the boat, and he steers accordingly.” This is in contrast to the European navigator who plots a course “and he carries out his voyage by relating his every move to that plan. His effort throughout his voyage is directed to remaining ‘on course’."

- on rms / necessary but not sufficient (p1k3) — "To the extent that free software was about wanting the freedom to hack and freely exchange the fruits of your hacking, this hasn’t gone so badly. It could be better, but I remember the 1990s pretty well and I can tell you that much of the stuff trivially at my disposal now would have blown my tiny mind back then. Sometimes I kind of snap to awareness in the middle of installing some package or including some library in a software project and this rush of gratitude comes over me."

- Screen time is good for you—maybe (MIT Technology Review) — "Przybylski admitted there are some drawbacks to his team’s study: demographic effects, like socioeconomics, are tied to psychological well-being, and he said his team is working to differentiate those effects—along with the self-selection bias introduced when kids and their caregivers report their own screen use. He also said he was working to figure out whether a certain type of screen use was more beneficial than others."

- This Map Lets You Plug in Your Address to See How It’s Changed Over the Past 750 Million Years (Smithsonian Magazine) — "Users can input a specific address or more generalized region, such as a state or country, and then choose a date ranging from zero to 750 million years ago. Currently, the map offers 26 timeline options, traveling back from the present to the Cryogenian Period at intervals of 15 to 150 million years."

- Understanding extinction — humanity has destroyed half the life on Earth (CBC) — "One of the most significant ways we've reduced the biomass on the planet is by altering the kind of life our planet supports. One huge decrease and shift was due to the deforestation that's occurred with our increasing reliance on agriculture. Forests represent more living material than fields of wheat or soybeans."

- Honks vs. Quacks: A Long Chat With the Developers of 'Untitled Goose Game' (Vice) — "[L]ike all creative work, this game was made through a series of political decisions. Even if this doesn’t explicitly manifest in the text of the game, there are a bunch of ambient traces of our politics evident throughout it: this is why there are no cops in the game, and why there’s no crown on the postbox."

- What is the Zeroth World, and how can we use it? (Bryan Alexander) — "[T]he idea of a zeroth world is also a critique. The first world idea is inherently self-congratulatory. In response, zeroth sets the first in some shade, causing us to see its flaws and limitations. Like postmodern to modern, or Internet2 to the rest of the internet, it’s a way of helping us move past the status quo."

- It’s not the claim, it’s the frame (Hapgood) — "[A] news-reading strategy where one has to check every fact of a source because the source itself cannot be trusted is neither efficient nor effective. Disinformation is not usually distributed as an entire page of lies.... Even where people fabricate issues, they usually place the lies in a bed of truth."

- Teens 'not damaged by screen time', study finds (BBC Technology) — "The analysis is robust and suggests an overall population effect too small to warrant consideration as a public health problem. They also question the widely held belief that screens before bedtime are especially bad for mental health."

- Human Contact Is Now a Luxury Good (The New York Times) — "The rich have grown afraid of screens. They want their children to play with blocks, and tech-free private schools are booming. Humans are more expensive, and rich people are willing and able to pay for them. Conspicuous human interaction — living without a phone for a day, quitting social networks and not answering email — has become a status symbol."

- NHS sleep programme ‘life changing’ for 800 Sheffield children each year (The Guardian) — "Families struggling with children’s seriously disrupted sleep have seen major improvements by deploying consistent bedtimes, banning sugary drinks in the evening and removing toys and electronics from bedrooms."

- While some children took part in organised after school clubs at least about one a week, not many of them did other or more spontaneous activities (e.g. physically meeting friends or cultivating hobbies) on a regular basis

- Many children used social media and other messaging platforms (e.g. chat functions in games) to continually keep in touch with their friends while at home

- Often children described going out to meet friends face-to-face as ‘too much effort’ and preferred to spend their free time on their own at home

- While some children managed to fit screen time around other offline interests and passions, for many, watching videos was one of the main activities taking up their spare time

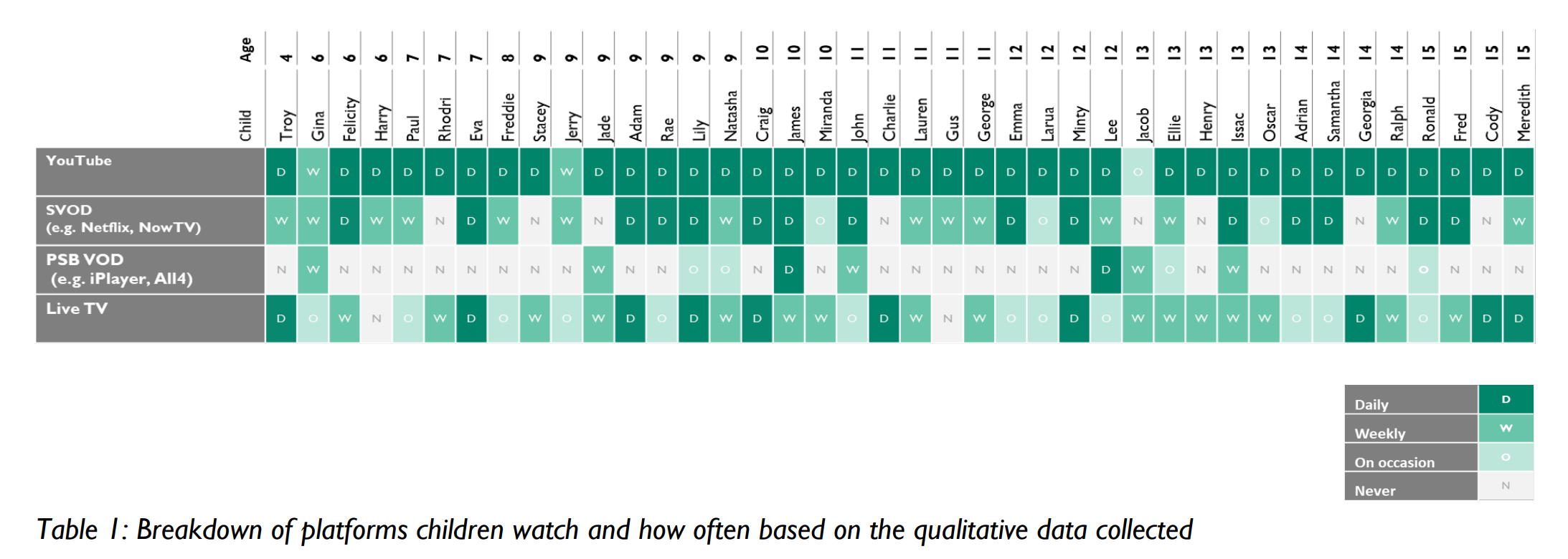

- YouTube was the most popular platform for children to consume video content, followed by Netflix. Although still present in many children’s lives, Public Service Broadcasters Video On Demand] platforms and live TV were used more rarely and seen as less relevant to children like them

- Many parents had attempted to enforce rules about online video watching, especially with younger children. They worried that they could not effectively monitor it, as opposed to live or on-demand TV, which was usually watched on the main TV. Some were frustrated by the amount of time children were spending on personal screens.

- The appeal of YouTube also appeared rooted in the characteristics of specific genres of content.

- Some children who watched YouTubers and vloggers seemed to feel a sense of connection with them, especially when they believed that they had something in common

- Many children liked “satisfying” videos which simulated sensory experiences

- Many consumed videos that allowed them to expand on their interests; sometimes in conjunction to doing activities themselves, but sometimes only pursuing them by watching YouTube videos

- These historically ‘offline’ experiences were part of YouTube’s attraction, potentially in contrast to the needs fulfilled by traditional TV.

Taste ripens at the expense of happiness

🧐 Habits, Data, and Things That Go Bump in the Night: Microsoft for Education — "Microsoft’s ubiquity, however, is sometimes mistaken for banality. Because it is everywhere, because we have all used it forever, we assume we can trust it."

I haven't voluntarily used something made by Microsoft (as opposed to acquired by it) for... about 20 years?

⏳ You Can Set Screen-Time Rules That Don’t Ruin Your Kids’ Lives — "Bear in mind that the limits you set need not be a specific number of minutes. Try to think of other, more natural ways of breaking up their activities. Maybe your kids play one game before tackling homework. Also, consider granting them one day per weekend with fewer restrictions on screen-time socializing. Giving them more autonomy over their weekends helps approximate the fun and flexibility of their pre-COVID world, and lets them unwind and hang out more with their friends."

This has been really hard to managed as a parent, and it's easy to think that you're always doing it wrong.

💬 Why do we keep on telling others what to do? — "Usually starting a conversation out with telling people what you feel they are doing wrong is going to make it a negative conversation all in all, and I tend to believe that it's better to follow “the campfire rule”, try to make all people taking part in a conversation end up a bit better off than what they were when they started the conversation, and telling people what to do or what not to are going straight against this."

Post-therapy, I'm much better at focusing on changing myself than trying to change others. I'd recommend therapy, but that might be construed as an implicit instruction...

🙌 Twitter Considers Subscription Fee for Tweetdeck, Unique Content — "To explore potential options outside ad sales, a number of Twitter teams are researching subscription offerings, including one using the code name “Rogue One,” according to people familiar with the effort. At least one idea being considered is related to “tipping,” or the ability for users to pay the people they follow for exclusive content, said the people, who asked not to be named because the discussions are internal. Other possible ways to generate recurring revenue include charging for the use of services like Tweetdeck or advanced user features like “undo send” or profile-customization options."

This is fantastic news. It would destroy Twitter as it currently stands, but that's fine as it's much worse than it was a decade ago.

🔒 Do lockdowns work? — "It's absurd thinking, but the sceptics have finally found an argument that cannot be categorically disproved. Lockdowns have a scientific rational: you can't transmit a virus to people you don't meet. Contrary to what Toby says in his article, they also have historic precedents: during the Spanish Flu, cities such as Philadelphia closed shops, churches, schools, bars and restaurants by law (they also made face masks mandatory). And now we have numerous natural experiments from around the world showing that infection rates fall when lockdowns are introduced."

There will always be idiots who try and use their influence and eloquence to ensure they're heard. Thankfully, there are people like this who can dismantle their arguments brick-by-brick.

Quotation-as-title by Jules Renard. Image. by Elena Mozhvilo.

Friday facilitations

This week, je presente...

Image of hugelkultur bed via Sid

Cutting the Gordian knot of 'screen time'

Let's start this with an admission: my wife and I limit our children's time on their tablets, and they're only allowed on our games console at weekends. Nevertheless, I still maintain that wielding 'screen time' as a blunt instrument does more harm than good.

There's a lot of hand-wringing on this subject, especially around social skills and interaction. Take a recent article in The Guardian, for example, where Peter Fonagy, who is a professor of Contemporary Psychoanalysis and Developmental Science at UCL, comments:

“My impression is that young people have less face-to-face contact with older people than they once used to. The socialising agent for a young person is another young person, and that’s not what the brain is designed for.

“It is designed for a young person to be socialised and supported in their development by an older person. Families have fewer meals together as people spend more time with friends on the internet. The digital is not so much the problem – it’s what the digital pushes out.”

I don't disagree that we all need a balance here, but where's the evidence? On balance, I spend more time with my children than my father spent with my sister and I, yet my wife, two children and me probably have fewer mealtimes sat down at a table together than I did with my parents and sister. Different isn't always worse, and in our case it's often due to their sporting commitments.

So I'd agree with Jordan Shapiro who writes that the World Health Organisation's guidelines on screen time for kids isn't particularly useful. He quotes several sources that dismiss the WHO's recommendations:

Andrew Przybylski, the Director of Research at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, said: “The authors are overly optimistic when they conclude screen time and physical activity can be swapped on a 1:1 basis.” He added that, “the advice overly focuses on quantity of screen time and fails to consider the content and context of use. Both the American Academy of Pediatricians and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health now emphasize that not all screen time is created equal.”

That being said, parents still need some guidance. As I've said before, my generation of parents are the first ones having to deal with all of this, so where do we turn for advice?

An article by Roja Heydarpour suggests three strategies, including one from Mimi Ito who I hold in the utmost respect for her work around Connected Learning:

“Just because [kids] may meet an unsavory person in the park, we don’t ban them from outdoor spaces,” said Mimi Ito, director of the Connected Learning Lab at University of California-Irvine, at the 10th annual Women in the World Summit on Thursday. After years of research, the mother of two college-age children said she thinks parents need to understand how important digital spaces are to children and adjust accordingly.

Taking away access to these spaces, she said, is taking away what kids perceive as a human right. Gaming is like the proverbial water cooler for many boys, she said. And for many girls, social media can bring access to friends and stave off social isolation. “We all have to learn how to regulate our media consumption,” Ito said. “The longer you delay kids being able to use those muscles, the longer you delay kids learning how to regulate.”

I feel a bit bad reading that, as we've recently banned my son from the game Fortnite, which we felt was taking over his life a little too much. It's not forever, though, and he does have to find that balance between it having a place in his life and literally talking about it all of the freaking time.

One authoritative voice in the area is my friend and sometimes collaborator Ian O'Byrne, who, together with Kristen Hawley Turner, has created screentime.me which features a blog, podcast, and up-to-date research on the subject. Well worth checking out!

Also check out:

What UK children are watching (and why)

There were only 40 children as part of this Ofcom research, and (as far as I can tell) none were in the North East of England where I live. Nevertheless, as parent to a 12 year-old boy and eight year-old girl, I found the report interesting.

Key findings:I've recently volunteered as an Assistant Scout Leader, and last night went with Scouts and Cubs to the ice-rink in Newcastle on the train. As I'd expect, most of the 12 year-old boys had their smartphones out and most of the girls were talking to one another. The boys were playing some games, but were mostly watching YouTube videos of other people playing games.

All kids with access to screen watch YouTube. Why?

Until I saw my son really level up his gameplay by watching YouTubers play the same games as him, I didn't really get it. There's lots of moral panic about YouTube's algorithms, but there's also a lot to celebrate with the fact that children have a bit more autonomy and control these days.

The appeal of YouTube for many of the children in the sample seemed to be that they were able to feed and advance their interests and hobbies through it. Due to the variety of content available on the platform, children were able to find videos that corresponded with interests they had spoken about enjoying offline; these included crafts, sports, drawing, music, make-up and science. Notably, in some cases, children were watching people on YouTube pursuing hobbies that they did not do themselves or had recently given up offline.Really interesting stuff, and well worth digging into!

Source: Ofcom (via Benedict Evans)

Let's (not) let children get bored again

Is boredom a good thing? Is there a direct link between having nothing to do and being creative? I’m not sure. Pamela Paul, writing in The New York Times, certainly thinks so:

Paul doesn't give any evidence beyond anecdote for boredom being 'good for you'. She gives a post hoc argument stating that because someone's creative life came after (what they remembered as) a childhood punctuated by boredom, the boredom must have caused the creativity.[B]oredom is something to experience rather than hastily swipe away. And not as some kind of cruel Victorian conditioning, recommended because it’s awful and toughens you up. Despite the lesson most adults learned growing up — boredom is for boring people — boredom is useful. It’s good for you.

I don’t think that’s true at all. You need space to be creative, but that space isn’t physical, it’s mental. You can carve it out in any situation, whether that’s while watching a TV programme or staring out of a window.

For me, the elephant in the room here is the art of parenting. Not a week goes by without the media beating up parents for not doing a good enough job. This is particularly true of the bizarre concept of ‘screentime’ (something that Ian O’Byrne and Kristen Turner are investigating as part of a new project).

In the article, Paul admits that previous generations ‘underparented’. However, in her article she creates a false dichotomy between that and ‘relentless’ modern helicopter parents. Where’s the happy medium that most of us inhabit?

So parents who provide for their children by enrolling them in classes and activities to explore and develop their talents are somehow doing them a disservice? I don't get it. Fair enough if they're forcing them into those activities, but I don't know too many parents who are doing that.Only a few short decades ago, during the lost age of underparenting, grown-ups thought a certain amount of boredom was appropriate. And children came to appreciate their empty agendas. In an interview with GQ magazine, Lin-Manuel Miranda credited his unattended afternoons with fostering inspiration. “Because there is nothing better to spur creativity than a blank page or an empty bedroom,” he said.

Nowadays, subjecting a child to such inactivity is viewed as a dereliction of parental duty. In a much-read story in The Times, “The Relentlessness of Modern Parenting,” Claire Cain Miller cited a recent study that found that regardless of class, income or race, parents believed that “children who were bored after school should be enrolled in extracurricular activities, and that parents who were busy should stop their task and draw with their children if asked.”

Ultimately, Paul and I have very different expectations and experiences of adult life. I don’t expect to be bored whether at work our out of it. There’s so much to do in the world, online and offline, that I don’t particularly get the fetishisation of boredom. To me, as soon as someone uses the word ‘realistic’, they’ve lost the argument:

No, perhaps we should make more engaging, and provide more than bullshit jobs. Perhaps we should seek out interesting things ourselves, so that our children do likewise?But surely teaching children to endure boredom rather than ratcheting up the entertainment will prepare them for a more realistic future, one that doesn’t raise false expectations of what work or life itself actually entails. One day, even in a job they otherwise love, our kids may have to spend an entire day answering Friday’s leftover email. They may have to check spreadsheets. Or assist robots at a vast internet-ready warehouse.

This sounds boring, you might conclude. It sounds like work, and it sounds like life. Perhaps we should get used to it again, and use it to our benefit. Perhaps in an incessant, up-the-ante world, we could do with a little less excitement.

Source: The New York Times