Most human beings have an almost infinite capacity for taking things for granted

So said Aldous Huxley. Recently, I discovered a episode of the podcast The Science of Success in which Dan Carlin was interviewed. Now Dan is the host of one of my favourite podcasts, Hardcore History as well as one he's recently discontinued called Common Sense.

The reason the latter is on 'indefinite hiatus' was discussed on The Science of Success podcast. Dan feels that, after 30 years as a journalist, if he can't get a grip on the current information landscape, then who can? It's shaken him up a little.

One of the quotations he just gently lobbed into the conversation was from John Stuart Mill, who at one time or another was accused by someone of being 'inconsistent' in his views. Mill replied:

When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?

John Stuart Mill

Now whether or not Mill said those exact words, the sentiment nevertheless stands. I reckon human beings have always made up their minds first and then chosen 'facts' to support their opinions. These days, I just think that it's easier than ever to find 'news' outlets and people sharing social media posts to support your worldview. It's as simple as that.

Last week I watched a stand-up comedy routine by Kevin Bridges on BBC iPlayer as part of his 2018 tour. As a Glaswegian, he made the (hilarious) analogy of social media as being like going into a pub.

(As an aside, this is interesting, as a decade ago people would often use the analogy of using social media as being like going to an café. The idea was that you could overhear, and perhaps join in with, interesting conversations that you hear. No-one uses that analogy any more.)

Bridges pointed out that if you entered a pub, sat down for a quiet pint, and the person next to you was trying to flog you Herbalife products, constantly talking about how #blessed they felt, or talking ambiguously for the sake of attention, you'd probably find another pub.

He was doing it for laughs, but I think he was also making a serious point. Online, we tolerate people ranting on and generally being obnoxious in ways we would never do offline.

The underlying problem of course is that any platform that takes some segment of the real world and brings it into software will also bring in all that segment's problems. Amazon took products and so it has to deal with bad and fake products (whereas one might say that Facebook took people, and so has bad and fake people).

Benedict Evans

I met Clay Shirky at an event last month, which kind of blew my mind given that it was me speaking at it rather than him. After introducing myself, we spoke for a few minutes about everything from his choice of laptop to what he's been working on recently. Curiously, he's not writing a book at the moment. After a couple of very well-received books (Here Comes Everybody and Cognitive Surplus) Shirky has actually only published a slightly obscure book about Chinese smartphone manufacturing since 2010.

While I didn't have time to dig into things there and then, and it would been a bit presumptuous of me to do so, it feels to me like Shirky may have 'walked back' some of his pre-2010 thoughts. This doesn't surprise me at all, given that many of the rest of us have, too. For example, in 2014 he published a Medium article explaining why he banned his students from using laptops in lectures. Such blog posts and news articles are common these days, but it felt like was one of the first.

The last decade from 2010 to 2019, which Audrey Watters has done a great job of eviscerating, was, shall we say, somewhat problematic. The good news is that we connected 4.5 billion people to the internet. The bad news is that we didn't really harness that for much good. So we went from people sharing pictures of cats, to people sharing pictures of cats and destroying western democracy.

Other than the 'bad and fake people' problem cited by Ben Evans above, another big problem was the rise of surveillance capitalism. In a similar way to climate change, this has been repackaged as a series of individual failures on the part of end users. But, as Lindsey Barrett explains for Fast Company, it's not really our fault at all:

In some ways, the tendency to blame individuals simply reflects the mistakes of our existing privacy laws, which are built on a vision of privacy choices that generally considers the use of technology to be a purely rational decision, unconstrained by practical limitations such as the circumstances of the user or human fallibility. These laws are guided by the idea that providing people with information about data collection practices in a boilerplate policy statement is a sufficient safeguard. If people don’t like the practices described, they don’t have to use the service.

Lindsey Barrett

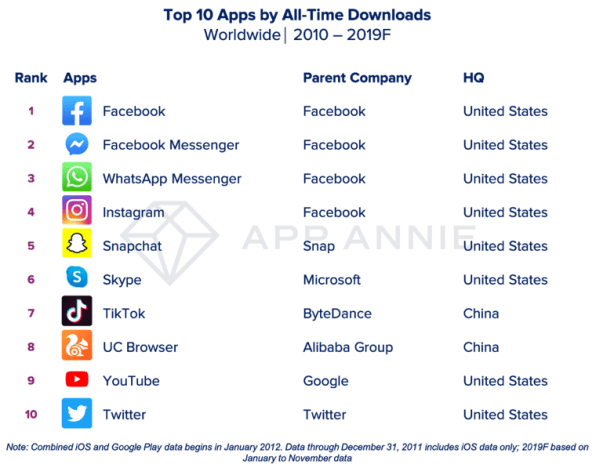

The problem is that we have monopolistic practices in the digital world. Fast Company also reports the four most downloaded apps of the 2010s were all owned by Facebook:

I don't actually think people really understand that their data from WhatsApp and Instagram is being hoovered up by Facebook. I don't then think they understand what Facebook then do with that data. I tried to lift the veil on this a little bit at the event where I met Clay Shirky. I know at least one person who immediately deleted their Facebook account as a result of it. But I suspect everyone else will just keep on keeping on. And yes, I have been banging my drum about this for quite a while now. I'll continue to do so.

The truth is, and this is something I'll be focusing on in upcoming workshops I'm running on digital literacies, that to be an 'informed citizen' these days means reading things like the EFF's report into the current state of corporate surveillance. It means deleting accounts as a result. It means slowing down, taking time, and reading stuff before sharing it on platforms that you know care for the many, not the few. It means actually caring about this stuff.

All of this might just look and feel like a series of preferences. I prefer decentralised social networks and you prefer Facebook. Or I like to use Signal and you like WhatsApp. But it's more than that. It's a whole lot more than that. Democracy as we know it is at stake here.

As Prof. Scott Galloway has discussed from an American point of view, we're living in times of increasing inequality. The tools we're using exacerbate that inequality. All of a sudden you have to be amazing at your job to even be able to have a decent quality of life:

The biggest losers of the decade are the unremarkables. Our society used to give remarkable opportunities to unremarkable kids and young adults. Some of the crowding out of unremarkable white males, including myself, is a good thing. More women are going to college, and remarkable kids from low-income neighborhoods get opportunities. But a middle-class kid who doesn’t learn to code Python or speak Mandarin can soon find she is not “tracking” and can’t catch up.

Prof. Scott Galloway

I shared an article last Friday, about how you shouldn't have to be good at your job. The whole point of society is that we look after one another, not compete with one another to see which of us can 'extract the most value' and pile up more money than he or she can ever hope to spend. Yes, it would be nice if everyone was awesome at all they did, but the optimisation of everything isn't the point of human existence.

So once we come down the stack from social networks, to surveillance capitalism, to economic and markets eating the world we find the real problem behind all of this: decision-making. We've sacrificed stability for speed, and seem to be increasingly happy with dictator-like behaviour in both our public institutions and corporate lives.

Dictatorships can be more efficient than democracies because they don’t have to get many people on board to make a decision. Democracies, by contrast, are more robust, but at the cost of efficiency.

Taylor Pearson

A selectorate, according to Pearson, "represents the number of people who have influence in a government, and thus the degree to which power is distributed". Aside from the fact that dictatorships tend to be corrupt and oppressive, they're just not a good idea in terms of decision-making:

Said another way, much of what appears efficient in the short term may not be efficient but hiding risk somewhere, creating the potential for a blow-up. A large selectorate tends to appear to be working less efficiently in the short term, but can be more robust in the long term, making it more efficient in the long term as well. It is a story of the Tortoise and the Hare: slow and steady may lose the first leg, but win the race.

Taylor Pearson

I don't think we should be optimising human beings for their role in markets. I think we should be optimising markets (if in fact we need them) for their role in human flourishing. The best way of doing that is to ensure that we distribute power and decision-making well.

So it might seem that my continual ragging on Facebook (in particular) is a small thing in the bigger picture. But it's actually part of the whole deal. When we have super-powerful individuals whose companies have the ability to surveil us at will; who then share that data to corrupt regimes; who in turn reinforce the worst parts of the status quo; then I think we have a problem.

This year I've made a vow to be more radical. To speak my mind even more, and truth to power, especially when it's inconvenient. I hope you'll join me ✊