The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason

I always enjoy reading L.M. Sacasas' thoughts on the intersection of technology, society, and ethics. This article is no different. In addition to the quotation from G.K. Chesterton which provides the title for this post, Sacasas also quotes Wendell Berry as saying, “It is easy for me to imagine that the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines."

While I’ve chosen to highlight the part riffing off David Noble’s discussion of technology as religion, I’d highly recommend reading the last three paragraphs of Sacasas' article. In it, he talks about AI as being “the culmination of a longstanding trajectory… [towards] the eclipse of the human person”.

The late David Noble’s The Religion of Technology: The Divinity of Man and the Spirit of Invention, first published in 1997, is a book that I turn to often. Noble was adamant about the sense in which readers should understand the phrase “religion of technology.” “Modern technology and modern faith are neither complements nor opposites,” Noble argued, “nor do they represent succeeding stages of human development. They are merged, and always have been, the technological enterprise being, at the same time, an essentially religious endeavor.”Source: Apocalyptic AI | The Convivial Society[…]

The Enlightenment did not, as it turns out, vanquish Religion, driving it far from the pure realms of Science and Technology. In fact, to the degree that the radical Enlightenment’s assault on religious faith was successful, it empowered the religion of technology. To put this another way, the Enlightenment—and, yes, we are painting with broad strokes here—did not do away with the notions of Providence, Heaven, and Grace. Rather, the Enlightenment re-framed these as Progress, Utopia, and Technology respectively. If heaven had been understood as a transcendent goal achieved with the aid of divine grace within the context of the providentially ordered unfolding of human history, it became a Utopian vision, a heaven on earth, achieved by the ministrations Science and Technology within the context of Progress, an inexorable force driving history toward its Utopian consummation.

[…]

In other words, we might frame the religion of technology not so much as a Christian heresy, but rather as (post-)Christian fan-fiction, an elaborate imagining of how the hopes articulated by the Christian faith will materialize as a consequence of human ingenuity in the absence of divine action.

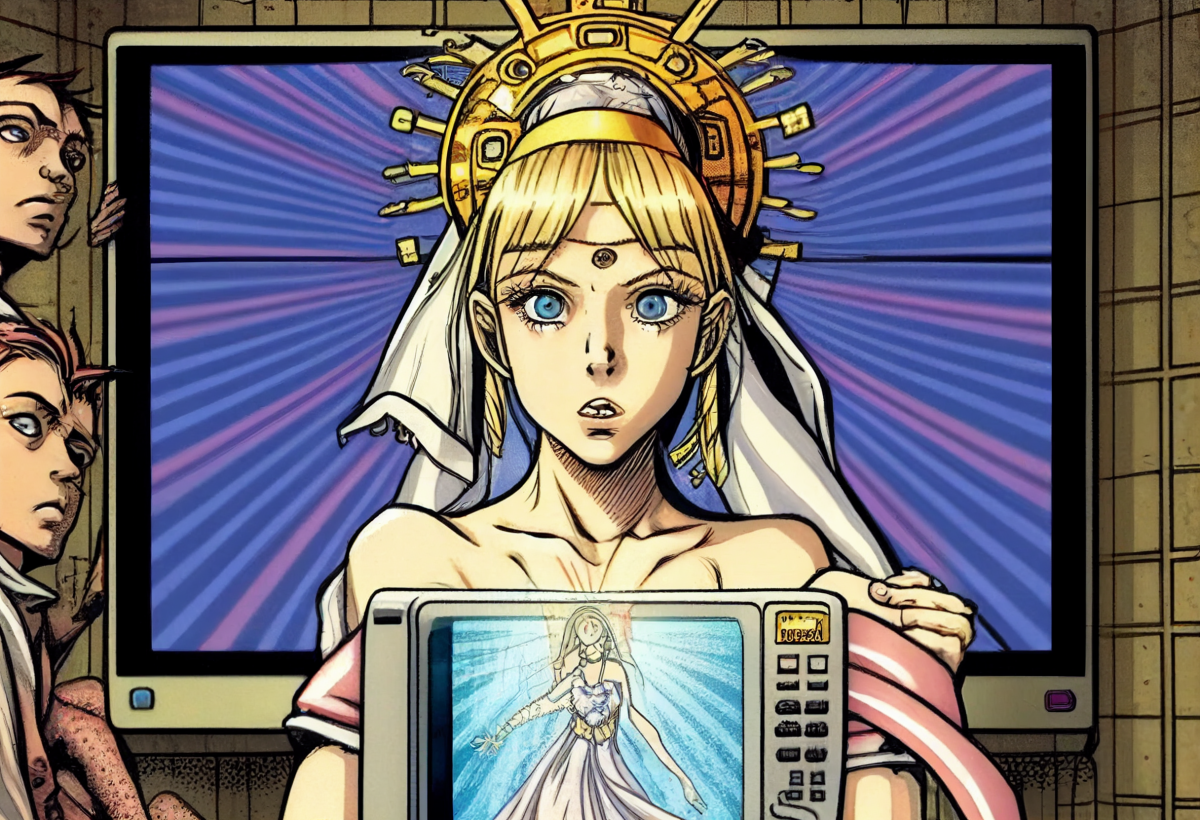

Image: Midjourney (see alt text for prompt)

Lifehouses, not churches

We used to go to church regularly. Then, as the kids grew older and sporting fixtures took over the weekend, we started going sporadically. Then, after the pandemic, we stopped going altogether. It seems we weren’t alone, as attendance, which was already declining, has fallen sharply. In fact, around 25% of Anglican churches no longer hold weekly services.

So what are we to do with these buildings? There are two massive ones at the end of our road, and a third was converted into a house a couple of decades ago. Writing in The Guardian, Simon Jenkins suggests we need to reconnect the buildings with the communities which surround them.

Throughout history these buildings have offered their publics ceremony and memorial, peace and meditation, charity and friendship, quite apart from faith. It is wrong that modern communities do not use them for such – or any other – purposes merely because religion has declined. They were built on the tithes of rich and poor alike.Adam Greenfield expands on this with the concept of 'Lifehouses'. He discusses this in a Mastodon thread with the following quotation coming from his newsletter:[…]

It is senseless to expect the Church of England to find the money to maintain these places into the future. The solution must be to reconnect them to the surrounding communities from which the decline in worship has distanced them. They must be wholly or partly secularised. This is happening across Europe, where churches are being brought under the aegis of local councils. They can benefit from a specific – usually small – local “church tax” which, in countries such as Sweden and Germany, is voluntary. This has been the churches’ salvation.

The fundamental idea of the Lifehouse is that there should be a place in every three-four city-block radius where you can charge your phone when the power’s down everywhere else, draw drinking water when the supply from the mains is for whatever reason untrustworthy, gather with your neighbors to discuss and deliberate over matters of common concern, organize reliable childcare, borrow tools it doesn’t make sense for any one household to own individually, and so on, and that these can and should be one and the same place. As a foundation for collective resourcefulness, the Lifehouse is a practical implementation of solarpunk values, and it’s eminently doable.Source: The decline of churchgoing doesn’t have to mean the decline of churches – they can help us level up | The Guardian[…]

And of course, in longer-established neighborhoods, there will often already be a building or physical site that organically serves many of these functions – the neighborhood’s naturally-arising Schelling Point, or node of unconscious coordination. Whether church, mosque, synagogue, high-school gym or public library, it will be where people instinctively turn for shelter and aid in times of trouble. What I believe our troubled times now ask of us is that we be more conscious and purposive about creating loose networks of such places, each of them provisioned against the hour of maximum need.