- Study shows some political beliefs are just historical accidents (Ars Technica) — "Obviously, these experiments aren’t exactly like the real world, where political leaders can try to steer their parties. Still, it’s another way to show that some political beliefs aren’t inviolable principles—some are likely just the result of a historical accident reinforced by a potent form of tribal peer pressure. And in the early days of an issue, people are particularly susceptible to tribal cues as they form an opinion."

- Please, My Digital Archive. It’s Very Sick. (Lapham's Quarterly) — "An archivist’s dream is immaculate preservation, documentation, accessibility, the chance for our shared history to speak to us once more in the present. But if the preservation of digital documents remains an unsolvable puzzle, ornery in ways that print materials often aren’t, what good will our archiving do should it become impossible to inhabit the world we attempt to preserve?"

- So You’re 35 and All Your Friends Have Already Shed Their Human Skins (McSweeney's) — "It’s a myth that once you hit 40 you can’t slowly and agonizingly mutate from a human being into a hideous, infernal arachnid whose gluttonous shrieks are hymns to the mad vampire-goddess Maggorthulax. You have time. There’s no biological clock ticking. The parasitic worms inside you exist outside of our space-time continuum."

- Investing in Your Ordinary Powers (Breaking Smart) — "The industrial world is set up to both encourage and coerce you to discover, as early as possible, what makes you special, double down on it, and build a distinguishable identity around it. Your specialness-based identity is in some ways your Industrial True Name. It is how the world picks you out from the crowd."

- Browser Fingerprinting: An Introduction and the Challenges Ahead (The Tor Project) — "This technique is so rooted in mechanisms that exist since the beginning of the web that it is very complex to get rid of it. It is one thing to remove differences between users as much as possible. It is a completely different one to remove device-specific information altogether."

- What is a Blockchain Phone? The HTC Exodus explained (giffgaff) — "HTC believes that in the future, your phone could hold your passport, driving license, wallet, and other important documents. It will only be unlockable by you which makes it more secure than paper documents."

- Debate rages in Austria over enshrining use of cash in the constitution (EURACTIV) — "Academic and author Erich Kirchler, a specialist in economic psychology, says in Austria and Germany, citizens are aware of the dangers of an overmighty state from their World War II experience."

- Cory Doctorow: DRM Broke Its Promise (Locus magazine) — "We gave up on owning things – property now being the exclusive purview of transhuman immortal colony organisms called corporations – and we were promised flexibility and bargains. We got price-gouging and brittleness."

- Five Books That Changed Me In One Summer (Warren Ellis) — "I must have been around 14. Rayleigh Library and the Oxfam shop a few doors down the high street from it, which someone was clearly using to pay things forward and warp younger minds."

- You can cope on less than five hours' sleep

- Alcohol before bed boosts your sleep

- Watching TV in bed helps you relax

- If you're struggling to sleep, stay in bed

- Hitting the snooze button

- Snoring is always harmless

- The ‘Dark Ages’ Weren’t As Dark As We Thought (Literary Hub) — "At the back of our minds when thinking about the centuries when the Roman Empire mutated into medieval Europe we are unconsciously taking on the spurious guise of specific communities."

- An Easy Mode Has Never Ruined A Game (Kotaku) — "There are myriad ways video games can turn the dials on various systems to change our assessment of how “hard” they seem, and many developers have done as much without compromising the quality or integrity of their games."

- Millennials destroyed the rules of written English – and created something better (Mashable) — "For millennials who conduct so many of their conversations online, this creativity with written English allows us to express things that we would have previously only been conveyed through volume, cadence, tone, or body language."

- Page forward

- Page back

- Menu

- (Power/Sleep)

- Big Gods : how religion transformed cooperation and conflict by Ara Norenzayan

- Prosperity Without Growth : economics for a finite planet by Tim Jackson

- An Everyone Culture : becoming a deliberately developmental organization by Robert Kegan, Lisa Laskow Lahey, and Matthew L Miller

Reading is useless

I like this post by graduate student Beck Tench. Reading is useless, she says, in the same way that meditation is useless. It’s for its own sake, not for something else.

When I titled this post “reading is useless,” I was referring to a Zen saying that goes, “Meditation is useless.” It means that you meditate to meditate, not to use it for something. And like the saying, I’m being provocative. Of course reading is not useless. We read in useful ways all the time and for good reason. Reading expands our horizons, it helps us understand things, it complicates, it validates, it clarifies. There’s nothing wrong with reading (or meditating for that matter) with a goal in mind, but maybe there is something wrong if we feel we can’t read unless it’s good for something.Source: Reading is Useless: A 10-Week Experiment in Contemplative Reading | Beck TenchThis quarter’s experiment was an effort to allow myself space to “read to read,” nothing more and certainly nothing less. With more time and fewer expectations, I realized that so much happens while I read, the most important of which are the moments and hours of my life. I am smelling, hearing, seeing, feeling, even tasting. What I read takes up place in my thoughts, yes, and also in my heart and bones. My body, which includes my brain, reads along with me and holds the ideas I encounter.

This suggests to me that reading isn’t just about knowing in an intellectual way, it’s also about holding what I read. The things I read this quarter were held by my body, my dreams, my conversations with others, my drawings and journal entries. I mean holding in an active way, like holding something in your hands in front of you. It takes endurance and patience to actively hold something for very long. As scholars, we need to cultivate patience and endurance for what we read. We need to hold it without doing something with it right away, without having to know.

Better to write for yourself and have no public, than to write for the public and have no self

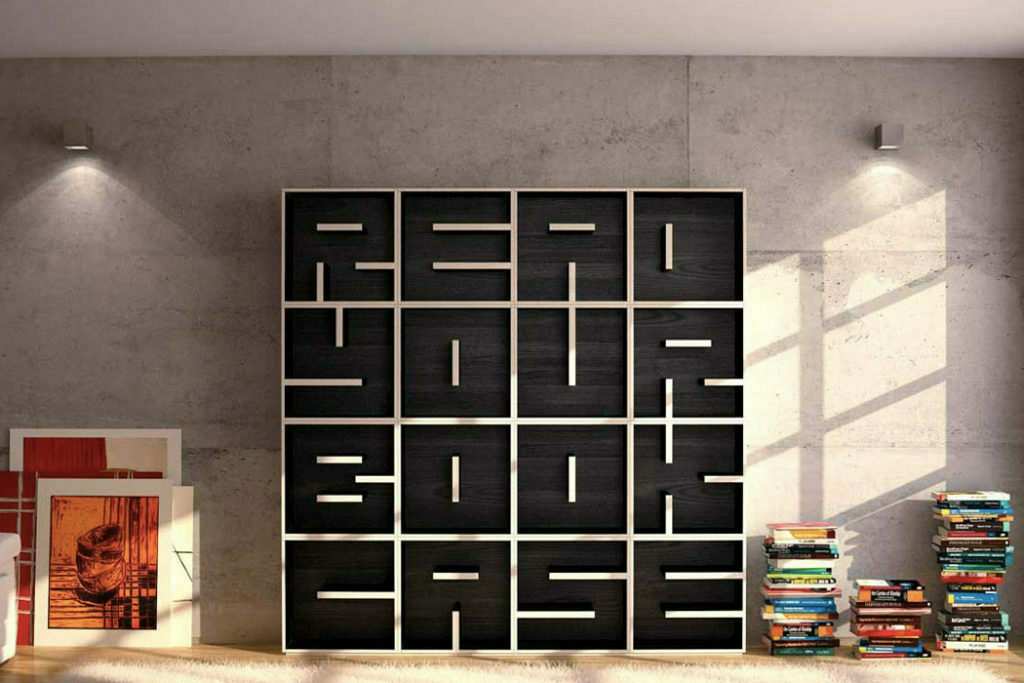

📚 Bookshelf designs as unique as you are: Part 2 — "Stuffing all your favorite novels into a single space without damaging any of them, and making sure the whole affair looks presentable as well? Now, that’s a tough task. So, we’ve rounded up some super cool, functional and not to mention aesthetically pleasing bookshelf designs for you to store your paperback companions in!"

📱 How to overcome Phone Addiction [Solutions + Research] — "Phone addiction goes hand in hand with anxiety and that anxiety often lowers the motivation to engage with people in real life. This is a huge problem because re-connecting with people in the offline world is a solution that improves the quality of life. The unnecessary drop in motivation because of addiction makes it that much harder to maintain social health."

⚙️ From Tech Critique to Ways of Living — "This technological enframing of human life, says Heidegger, first “endanger[s] man in his relationship to himself and to everything that is” and then, beyond that, “banishes” us from our home. And that is a great, great peril."

🎨 Finding time for creativity will give you respite from worries — "According to one study examining the links between art and health, a cost-benefit analysis showed a 37% drop in GP consultation rates and a 27% reduction in hospital admissions when patients were involved in creative pursuits. Other studies have found similar results. For example, when people were asked to write about a trauma for 15 minutes a day, it resulted in fewer subsequent visits to the doctor, compared to a control group."

🧑🤝🧑 For psychologists, the pandemic has shown people’s capacity for cooperation — "In short, what we have seen is a psychology of collective resilience supplanting a psychology of individual frailty. Such a shift has profound implications for the relationship between the citizen and the state. For the role of the state becomes less a matter of substituting for the deficiencies of the individual and more to do with scaffolding and supporting communal self-organisation."

Quotation-as-title by Cyril Connolly. Image from top-linked post.

Friday feudalism

Check out these things I discovered this week, and wanted to pass along:

Things that people think are wrong (but aren't)

I've collected a bunch of diverse articles that seem to be around the topic of things that people think are wrong, but aren't really. Hence the title.

I'll start with something that everyone over a certain age seems to have a problem with, except for me: sleep. BBC Health lists five sleep myths:

My smartband regularly tells me that I sleep better than 93% of people, and I think that's because of how much I prioritise sleep. I've also got a system, which I've written about before for the times when I do have a rough night.

I like routine, but I also like mixing things up, which is why I appreciate chunks of time at home interspersed with travel. Oliver Burkeman, writing in The Guardian, suggests, however, that routines aren't the be-all and end-all:

Some people are so disorganised that a strict routine is a lifesaver. But speaking as a recovering rigid-schedules addict, trust me: if you click excitedly on each new article promising the perfect morning routine, you’re almost certainly not one of those people. You’re one of the other kind – people who’d benefit from struggling less to control their day, responding a bit more intuitively to the needs of the moment. This is the self-help principle you might call the law of unwelcome advice: if you love the idea of implementing a new technique, it’s likely to be the opposite of what you need.

Expecting something new to solve an underlying problem is a symptom of our culture's focus on the new and novel. While there's so much stuff out there we haven't experienced, should we spend our lives seeking it out to the detriment of the tried and tested, the things that we really enjoy?

On the recommendation of my wife, I recently listened to a great episode of the Off Menu podcast featuring Victoria Cohen Mitchell. It's not only extremely entertaining, but she mentions how, for her, a nice Ploughman's lunch is better than some fancy meal.

This brings me to an article in The Atlantic by Joe Pinsker, who writes that kids who watch and re-watch the same film might be on to something:

In general, psychological and behavioral-economics research has found that when people make decisions about what they think they’ll enjoy, they often assign priority to unfamiliar experiences—such as a new book or movie, or traveling somewhere they’ve never been before. They are not wrong to do so: People generally enjoy things less the more accustomed to them they become. As O’Brien [professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business] writes, “People may choose novelty not because they expect exceptionally positive reactions to the new option, but because they expect exceptionally dull reactions to the old option.” And sometimes, that expected dullness might be exaggerated.

So there's something to be said for re-reading novels you read when you were younger instead of something shortlisted for a prize, or discounted in the local bookshop. I found re-reading Dostoevsky's Crime & Punishment recently exhilarating as I probably hadn't ready it since I became a parent. Different periods of your life put different spins on things that you think you already know.

Also check out:

Audiobooks vs reading

Although I listen to a lot of podcasts (here’s my OPML file) I don’t listen to many audiobooks. That’s partly because I never feel up-to-date with my podcast listening, but also because I often read before going to sleep. It’s much more difficult to find your place again if you drift off while listening than while reading!

This article in TIME magazine (is it still a ‘magazine’?) looks at the research into whether listening to an audiobook is like reading using your eyes. Well, first off, it would seem that there’s no difference in recall of facts given a non-fiction text:

For a 2016 study, Rogowsky put her assumptions to the test. One group in her study listened to sections of Unbroken, a nonfiction book about World War II by Laura Hillenbrand, while a second group read the same parts on an e-reader. She included a third group that both read and listened at the same time. Afterward, everyone took a quiz designed to measure how well they had absorbed the material. “We found no significant differences in comprehension between reading, listening, or reading and listening simultaneously,” Rogowsky says.However, the difficulty here is that there's already an observed discrepancy in recall between dead-tree books and e-books. So perhaps audiobooks are as good as e-books, but both aren't as good as printed matter?

There’s a really interesting point made in the article about how dead-tree books allow for a slight ‘rest’ while you’re reading:

If you’re reading, it’s pretty easy to go back and find the point at which you zoned out. It’s not so easy if you’re listening to a recording, Daniel says. Especially if you’re grappling with a complicated text, the ability to quickly backtrack and re-examine the material may aid learning, and this is likely easier to do while reading than while listening. “Turning the page of a book also gives you a slight break,” he says. This brief pause may create space for your brain to store or savor the information you’re absorbing.This reminds me of an article on Lifehacker a few years ago that quoted a YouTuber who swears by reading a book while also listening to it:

First of all, it combines two senses…so you end up with really good comprehension while being really efficient at the same time. ...Another possibly even more important benefit is…it keeps you going. So you’re not going back and rereading things, you’re not taking all kinds of unnecessary breaks and pauses, your eyes aren’t running around all the time, and you’re not getting distracted every two minutes.Since switching to an open source e-reader, I'm no longer using the Amazon Kindle ecosystem so much these days. If I were, I'd be experimenting with their WhisperSync technology that allows you to either pick up where you left up with one medium — or, indeed, use both at the same time.

Source: TIME / Lifehacker

The importance of marginalia

Austin Kleon makes a simple, but important point, about how to become a writer:

I believe that the first step towards becoming a writer is becoming a reader, but the next step is becoming a reader with a pencil. When you underline and circle and jot down your questions and argue in the margins, you’re existing in this interesting middle ground between reader and writer:Kleon has previously recommended Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren's How to Read a Book, which I bought last time he mentioned it. Ironically enough, it's sitting on my bookshelf, unread. Anyway, he quotes Adler and Van Doren as saying:

Full ownership of a book only comes when you have made it a part of yourself, and the best way to make yourself a part of it — which comes to the same thing — is by writing in it. Why is marking a book indispensable to reading it? First, it keeps you awake — not merely conscious, but wide awake. Second, reading, if it is active, is thinking, and thinking tends to express itself in words, spoken or written. The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks. Third, writing your reactions down helps you to remember the thoughts of the author. Reading a book should be a conversation between you and the author….Marking a book is literally an expression of your differences or your agreements…It is the highest respect you can pay him.I read a lot of non-fiction books on my e-reader*, so the equivalent of that for me is Thought Shrapnel, I guess...

Source: Austin Kleon

* Note: I left my old e-reader on the flight home from our holiday. I took the opportunity to upgrade to the bq Cervantes 4, which I bought from Amazon Spain.

Keeping track of articles you want to read

One of the things I like about Hacker News is that, as well as providing useful links to technically-minded stuff, there are also ‘Ask HN’ threads where a user asks a question of the rest of the community.

Ask HN: How do you keep track of articles you want to read?I don’t like the ‘inbox as to-do list’ method. Other HN users suggested alternatives, with the top-voted comment at the time of writing this being:When I browse HN, I usually pick out a few articles I want to read from the front page, then email the links to myself to read later.

This method works out pretty well for me. I’m wondering if people have other strategies that work better?

I used Instapaper (https://www.instapaper.com/), then moved to Pocket (https://getpocket.com/) to take advantage of the social features, then moved back to Instapaper for no really good reason. Pocket still looks nicer and the apps are more reliable, in my experience.Pocket is great, but I used IFTTT to automatically send RSS feeds there at one point, and now it seems to be in an endless sync loop.They both allow you to save the full text of an article to read later, as well as archiving and organizing articles you’ve already read. They sync to phones, so most of my reading actually happens on public transit. Pocket can also sync to a Kobo ebook reader; not sure about Kindle, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it worked with them, too.

Other HN users said that they pin bookmarks, and so have many, many tabs open at one time. I think that’s a hugely inefficient and resource-intensive approach.

Some kept it super-simple:

I use Org Mode so I have a plain text file called todo-bookmarks.org with a list of links to the articles I want to read.This caused me to think about what I do. If I want to read something, I actually add the link as a draft post here, on Thought Shrapnel. The best way to ensure I gain value from a potentially-interesting article is to write about it.

I’d rather write about a few links rather than bookmark lots. I’ve all but given up on bookmarking, as it’s almost as quick to search the web for something I’m looking for as it is to search my bookmarks…

Source: Hacker News

The benefits of reading aloud to children

This article in the New York Times by Perri Klass, M.D. focuses on studies that show a link between parents reading to their children and a reduction in problematic behaviour.

I really like the way that they focus on the positives and point out how much the child loves the interaction with their parent through the text.This study involved 675 families with children from birth to 5; it was a randomized trial in which 225 families received the intervention, called the Video Interaction Project, and the other families served as controls. The V.I.P. model was originally developed in 1998, and has been studied extensively by this research group.

Participating families received books and toys when they visited the pediatric clinic. They met briefly with a parenting coach working with the program to talk about their child’s development, what the parents had noticed, and what they might expect developmentally, and then they were videotaped playing and reading with their child for about five minutes (or a little longer in the part of the study which continued into the preschool years). Immediately after, they watched the videotape with the study interventionist, who helped point out the child’s responses.

I don't know enough about the causes of ADHD to be able to comment, but as a teacher and parent, I do know there's a link between the attention you give and the attention you receive.The Video Interaction Project started as an infant-toddler program, working with low-income urban families in New York during clinic visits from birth to 3 years of age. Previously published data from a randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development showed that the 3-year-olds who had received the intervention had improved behavior — that is, they were significantly less likely to be aggressive or hyperactive than the 3-year-olds in the control group.

It is a bit sad when we have to encourage parents to play with children between the ages of birth and three, but I guess in the age of smartphone addiction, we kind of have to.“The reduction in hyperactivity is a reduction in meeting clinical levels of hyperactivity,” Dr. Mendelsohn said. “We may be helping some children so they don’t need to have certain kinds of evaluations.” Children who grow up in poverty are at much higher risk of behavior problems in school, so reducing the risk of those attention and behavior problems is one important strategy for reducing educational disparities — as is improving children’s language skills, another source of school problems for poor children.

Source: The New York Times

Image CC BY Jason Lander

Craig Mod's subtle redesign of the hardware Kindle

I like Craig Mod’s writing. He’s the guy that’s written on his need to walk, drawing his own calendar, and getting his attention back.

This article is hardware Kindle devices — the distinction being important given that you can read your books via the Kindle Cloud Reader or, indeed, via an app on pretty much any platform.

As he points out, the user interface remains sub-optimal:

Tap most of the screen to go forward a page. Tap the left edge to go back. Tap the top-ish area to open the menu. Tap yet another secret top-right area to bookmark. This model co-opts the physical space of the page to do too much.He suggests an alternative to this which involves physical buttons on the device itself:The problem is that the text is also an interface element. But it’s a lower-level element. Activated through a longer tap. In essence, the Kindle hardware and software team has decided to “function stack” multiple layers of interface onto the same plane.

And so this model has never felt right.

I can see why he proposes this, but I'm not so sure about the physical buttons for page turns. The reason I'd say that, is that although I now use a Linux-based bq Cervantes e-reader, before 2015 I had almost every iteration of the hardware Kindle. There's a reason Amazon removed hardware buttons for page turns.Hardware buttons:

What does this get us?

It means we can now assume that — when inside of a book — any tap on the screen is explicitly to interact with content: text or images within the text. This makes the content a first-class object in the interaction model. Right now it’s secondary, engaged only if you tap and hold long enough on the screen. Otherwise, page turn and menu invocations take precedence.

I read in lots of places, but I read in bed with my wife every day and if there’s one thing she couldn’t stand, it was the clicking noise of me turning the page on my Kindle. Even if I tried to press it quietly, it annoyed her. Touchscreen page turns are much better.

The e-reader I use has a similar touch interaction to the Kindle, so I see where Craig Mod is coming from when he says:

This, if you haven't come across it before, is user interface design, or UI design for short. It's important stuff, for as Steve Jobs famously said: "Everything in this world... was created by people no smarter than you" — and that's particularly true in tech.When content becomes the first-class object, every interaction is suddenly bounded and clear. Want the menu? Press the (currently non-existent) menu button towards the top of the Kindle. Want to turn the page? Press the page turn button. Want to interact with the text? Touch it. Nothing is “hidden.” There is no need to discover interactions. And because each interaction is clear, it invites more exploration and play without worrying about losing your place.

Source: Craig Mod

To lose old styles of reading is to lose a part of ourselves

Sometimes I think we’re living in the end times:

I wrote my doctoral thesis on digital literacies. There was a real sense in the 1990s that reading on screen was very different to reading on paper. We've kind of lost that sense of difference, and I think perhaps we need to regain it:Out for dinner with another writer, I said, "I think I've forgotten how to read."

"Yes!" he replied, pointing his knife. "Everybody has."

"No, really," I said. "I mean I actually can't do it any more."

He nodded: "Nobody can read like they used to. But nobody wants to talk about it."

We don't really talk about 'hypertext' any more, as it's almost the default type of text that we read. As such, reading on paper doesn't really prepare us for it:For most of modern life, printed matter was, as the media critic Neil Postman put it, "the model, the metaphor, and the measure of all discourse." The resonance of printed books – their lineal structure, the demands they make on our attention – touches every corner of the world we've inherited. But online life makes me into a different kind of reader – a cynical one. I scrounge, now, for the useful fact; I zero in on the shareable link. My attention – and thus my experience – fractures. Online reading is about clicks, and comments, and points. When I take that mindset and try to apply it to a beaten-up paperback, my mind bucks.

Me too. I train myself to read longer articles through mechanisms such as writing Thought Shrapnel posts and newsletters each week. But I don't read like I used to; I read for utility rather than pleasure and just for the sake of it.For a long time, I convinced myself that a childhood spent immersed in old-fashioned books would insulate me somehow from our new media climate – that I could keep on reading and writing in the old way because my mind was formed in pre-internet days. But the mind is plastic – and I have changed. I'm not the reader I was.

It's funny. We've such a connection with books, but for most of human history we've done without them:The suggestion that, in a few generations, our experience of media will be reinvented shouldn't surprise us. We should, instead, marvel at the fact we ever read books at all. Great researchers such as Maryanne Wolf and Alison Gopnik remind us that the human brain was never designed to read. Rather, elements of the visual cortex – which evolved for other purposes – were hijacked in order to pull off the trick. The deep reading that a novel demands doesn't come easy and it was never "natural." Our default state is, if anything, one of distractedness. The gaze shifts, the attention flits; we scour the environment for clues. (Otherwise, that predator in the shadows might eat us.) How primed are we for distraction? One famous study found humans would rather give themselves electric shocks than sit alone with their thoughts for 10 minutes. We disobey those instincts every time we get lost in a book.

There's several theses in all of this around fake news, the role of reading in a democracy, and how information spreads. For now, I continue to be amazed at the power of the web on the fabric of societies.Literacy has only been common (outside the elite) since the 19th century. And it's hardly been crystallized since then. Our habits of reading could easily become antiquated. The writer Clay Shirky even suggests that we've lately been "emptily praising" Tolstoy and Proust. Those old, solitary experiences with literature were "just a side-effect of living in an environment of impoverished access." In our online world, we can move on. And our brains – only temporarily hijacked by books – will now be hijacked by whatever comes next.

Source: The Globe and Mail

Why we forget most of what we read

I read a lot of stuff, and I remember random bits of it. I used to be reasonably disciplined about bookmarking stuff, but then realised I hardly ever went back through my bookmarks. So, instead, I try to use what I read, which is kind of the reason for Thought Shrapnel…

Surely some people can read a book or watch a movie once and retain the plot perfectly. But for many, the experience of consuming culture is like filling up a bathtub, soaking in it, and then watching the water run down the drain. It might leave a film in the tub, but the rest is gone.Well, indeed. Nice metaphor.

In the internet age, recall memory—the ability to spontaneously call information up in your mind—has become less necessary. It’s still good for bar trivia, or remembering your to-do list, but largely, [Jared Horvath, a research fellow at the University of Melbourne] says, what’s called recognition memory is more important. “So long as you know where that information is at and how to access it, then you don’t really need to recall it,” he says.Exactly. You need to know how to find that article you read that backs up the argument you're making. You don't need to remember all of the details. Search skills are really important.

One study showed that recalling details about episodes for those bingeing on Netflix series was much lower than for thoose who spaced them out. I guess that’s unsurprising.

People are binging on the written word, too. In 2009, the average American encountered 100,000 words a day, even if they didn’t “read” all of them. It’s hard to imagine that’s decreased in the nine years since. In “Binge-Reading Disorder,” an article for The Morning News, Nikkitha Bakshani analyzes the meaning of this statistic. “Reading is a nuanced word,” she writes, “but the most common kind of reading is likely reading as consumption: where we read, especially on the internet, merely to acquire information. Information that stands no chance of becoming knowledge unless it ‘sticks.’”For anyone who knows about spaced learning, the conclusions are pretty obvious:

The lesson from his binge-watching study is that if you want to remember the things you watch and read, space them out. I used to get irritated in school when an English-class syllabus would have us read only three chapters a week, but there was a good reason for that. Memories get reinforced the more you recall them, Horvath says. If you read a book all in one stretch—on an airplane, say—you’re just holding the story in your working memory that whole time. “You’re never actually reaccessing it,” he says.So apply what you learn and you're putting it to work. Hence this post!

Source: The Atlantic (via e180)

Reading the web on your own terms

Although it was less than a decade ago since the demise of the wonderful, simple, much-loved Google Reader, it seems like it was a different age entirely.

Subscribing to news feeds and blogs via RSS wasn’t as widely used as it could/should have been, but there was something magical about that period of time.

In this article, the author reflects on that era and suggests that we might want to give it another try:

Well, I believe that RSS was much more than just a fad. It made blogging possible for the first time because you could follow dozens of writers at the same time and attract a considerably large audience if you were the writer. There were no ads (except for the high-quality Daring Fireball kind), no one could slow down your feed with third party scripts, it had a good baseline of typographic standards and, most of all, it was quiet. There were no comments, no likes or retweets. Just the writer’s thoughts and you.I was a happy user of Google Reader until they pulled the plug. It was a bit more interactive than other feed readers, somehow, in a way I can't quite recall. Everyone used it until they didn't.

The unhealthy bond between RSS and Google Reader is proof of how fragile the web truly is, and it reveals that those communities can disappear just as quickly as they bloom.Since that time I've been an intermittent user of Feedly. Everyone else, it seems, succumbed to the algorithmic news feeds provided by Facebook, Twitter, and the like.

A friend of mine the other day said that “maybe Medium only exists because Google Reader died — Reader left a vacuum, and the social network filled it.” I’m not entirely sure I agree with that, but it sure seems likely. And if that’s the case then the death of Google Reader probably led to the emergence of email newsletters, too.I don’t think we can turn the clock back, but it does feel like there might be positive, future-focused ways of improving things through, for example, decentralisation.[…]

On a similar note, many believe that blogging is making a return. Folks now seem to recognize the value of having your own little plot of land on the web and, although it’s still pretty complex to make your own website and control all that content, it’s worth it in the long run. No one can run ads against your thing. No one can mess with the styles. No one can censor or sunset your writing.

Not only that but when you finish making your website you will have gained superpowers: you now have an independent voice, a URL, and a home on the open web.

Source: Robin Rendle

Albert Wenger's reading list

Albert Wenger, a venture capitalist and author of World After Capital, invited his (sizeable) blog readership to suggest some books he should read over his Christmas and New Year’s break. The results are interesting, as there’s a mix of technical, business, and more discursive writing.

The ones that stood out for me were:

Source: Continuations

What you read determines who you are

Shane Parrish from Farnam Street has written an ‘annual letter’ to his audience, much like his hero Warren Buffett. I particularly liked this section:

The people you spend time with shape who you are. As Goethe said, “tell me with whom you consort and I will tell you who you are.” But Goethe didn’t know about the internet. It’s not just the people you spend your time with in person who shape you; the people you spend time with online shape you as well.Source: Farnam Street BlogTell me what you read on a regular basis and I will tell you what you likely think. Creepy? Think again. Facebook already knows more about you than your partner does. They know the words that resonate with you. They know how to frame things to get you to click. And they know the thousands of people who look at the same things online that you do.

When you’re reading something online, you’re spending time with someone. These people determine our standards, our defaults, and often our happiness.

Every year, I make a point of reflecting on how I’ve been spending my time. I ask myself who I’m spending my time with and what I’m reading, online and offline. The thread of these questions comes back to a common core: Is where I’m spending my time consistent with who I want to be?