You'll be hearing a lot more about nodules

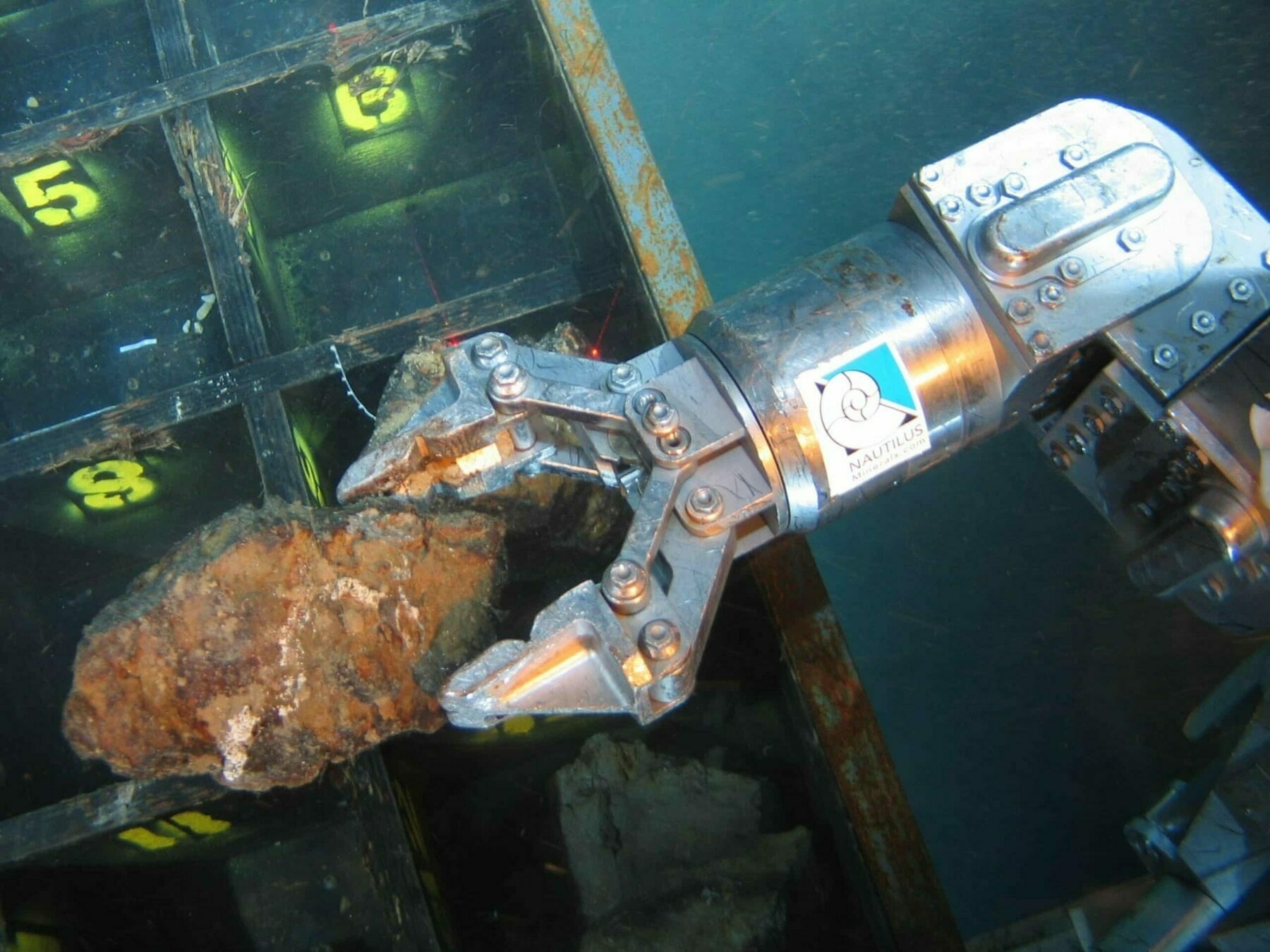

It was only this year that I first heard about nodules, rock-shaped objects formed over millions of years on the sea bed which contain rare earth minerals. We use these for making batteries and other technologies which may help us transition away from fossil fuels.

However, deep-sea mining is, understandably, a controversial topic. At a recent summit of the Pacific Islands Forum, The Cook Islands' Prime Minister outlined his support for exploration and highlighted its potential by gifting seabed nodules to fellow leaders.

This, of course, is a problem caused by capitalism, and the view that the natural world is a resource to be exploited by humans. We’re talking about something which is by definition a non-renewable resource. I think we need to tread (and dive) extremely carefully.

What’s black, shaped like a potato and found in the suitcases of Pacific leaders when they leave a regional summit in the Cook Islands this week? It’s called a seabed nodule, a clump of metallic substances that form at a rate of just centimetres over millions of years.Source: Here be nodules: will deep-sea mineral riches divide the Pacific family? | Deep-sea mining | The GuardianDeep-sea mining advocates say they could be the answer to global demand for minerals to make batteries and transform economies away from fossil fuels. The prime minister of the Cook Islands, Mark Brown, is offering nodules as mementos to fellow leaders from the Pacific Islands Forum (Pif), a bloc of 16 countries and two territories that wraps up its most important annual political meeting on Friday.

[…]

“Forty years of ocean survey work suggests as much as 6.7bn tonnes of mineral-rich manganese nodules, found at a depth of 5,000m, are spread over some 750,000 square kilometres of the Cook Islands continental shelf,” [the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority] says.

Our ancestors were using complex tools and woodworking approaches almost half a million years ago

Nature reports that, at the Kalambo Falls archaeological site in Zambia, researchers have unearthed the earliest known examples of woodworking — dating back at least 476,000 years. This is a significant find as it includes two logs interlocked by a hand-cut notch, a method previously unseen in early human history. The discovery also features four other wood tools: a wedge, digging stick, cut log, and a notched branch. These artifacts demonstrate early humans' advanced skills in shaping wood for various purposes, challenging the traditional view that early hominins primarily used stone tools.

I’ve also never heard of the approach that the team used: luminescence dating. This is a method that helps determine when the wood was last exposed to light, and various wood analysis techniques.

The findings, especially the interlocked logs, suggest that early humans had the capability to construct large structures and manipulate wood in complex ways. It’s a groundbreaking discovery, as it not only pushes back the timeline of woodworking in Africa but also sheds new light on the cognitive abilities and technological diversity of our early ancestors. Amazing.

The Quaternary sequence is a 9-m-deep exposure above the Kalambo River (BLB1 is a geological section). Sediments are fluvial sands and gravels with occasional, discontinuous beds of fine sands, silts and clays with wood preserved in the lowermost 2 m.... A permanently elevated water table has preserved wood and plant remains (Supplementary Information Section 1). The depositional sequence is typical of a high- to moderate-energy sandbed river that underwent lateral migration. The sands are dominated by a lower unit of horizontal bedding and an upper unit of planar/trough cross-bedding. Upper and lower sand units are separated by fine sands, silts and clays with plant material deposited in still water after the river migrated/avulsed elsewhere in the floodplain. Wood is deposited in this environment either through anthropogenic emplacement, or naturally transported in the flow, and snagged on sand bedforms.Source: Evidence for the earliest structural use of wood at least 476,000 years ago | Nature[…]

Sixteen samples for dating were collected at Site BLB by hammering opaque plastic tubes into the sediment. A combination of field gamma spectrometry, laboratory alpha and beta counting and geochemical analyses were used to determine radionuclide content, and the dose rate and age calculator42 was used to calculate radiation dose rate. Sand-sized grains (approximately 150 to 250 µm in diameter) of quartz and potassium-rich feldspar were isolated under red-light conditions for luminescence measurements and measured on Risø TL/OSL instruments using single-aliquot regenerative dose protocols. Single-grain quartz OSL measurements dated sediments younger than around 60 kyr, but beyond this age the OSL signal was saturated. pIR IRSL measurements of aliquots consisting of around 50 grains of potassium-rich feldspars were able to provide ages for all samples collected. The pIR IRSL signal yielded an average value for anomalous fading of 1.46 ± 0.50% per decade. Where quartz OSL and feldspar pIR IRSL were applied to the same samples, the ages were consistent within uncertainties without needing to correct for anomalous fading. The conservative approach taken here has been to use ages without any correction for fading. If a fading correction had been applied then the ages for the wooden artefacts would be older.

Pufflings can't resist the bright lights of the city

I haven’t seen puffins in real life very often, but they’re associated with the Farne Islands off the coast of Northumberland, my home county. They’re a bird associated with more northern climes, and are enigmatic creatures.

It’s both sad and heartening to see that, to save them going extinct in Iceland, locals have to stop them wandering towards the bright lights of human civilization. Instead, they take the baby puffins, which are adorably called ‘pufflings’, and throw them off cliffs to encourage them to fly.

Natural evolution can’t happen as fast as humans are changing the world, so unless we want to see the absolute devastation of biodiversity on our planet, traditions such as this are going to have to become commonplace.

Watching thousands of baby puffins being tossed off a cliff is perfectly normal for the people of Iceland's Westman Islands.Source: During puffling season, Icelanders save baby puffins by throwing them off cliffs | NPRThis yearly tradition is what’s known as “puffling season” and the practice is a crucial, life-saving endeavor.

The chicks of Atlantic puffins, or pufflings, hatch in burrows on high sea cliffs. When they’re ready to fledge, they fly from their colony and spend several years at sea until they return to land to breed, according to Audubon Project Puffin.

Pufflings have historically found the ocean by following the light of the moon, digital creator Kyana Sue Powers told NPR over a video call from Iceland. Now, city lights lead the birds astray.

[…]

Many residents of Vestmannaeyjar spend a few weeks in August and September collecting wayward pufflings that have crashed into town after mistaking human lights for the moon. Releasing the fledglings at the cliffs the following day sets them on the correct path.

This human tradition has become vital to the survival of puffins, Rodrigo A. Martínez Catalán of Náttúrustofa Suðurlands [South Iceland Nature Research Center] told NPR. A pair of puffins – which mate for life – only incubate one egg per season and don’t lay eggs every year.

“If you have one failed generation after another after another after another,” Catalán said, “the population is through, pretty much."

A trickle, a ripple, a slow rush

This article by Antonia Malchik reflects on her personal journey moving back to her hometown in Montana. It focuses on her deep sense of gratitude for the natural environment and community. She discusses the annual Gathering of the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance, celebrating the retirement of the last remaining oil lease in the area, which is significant for the Blackfeet Nation.

The part of the article in which I’m most interested is towards the end: a reflective moment by a creek. She writes about the importance of being present in nature and contemplating one’s place and responsibilities in the world. That feeling of being in and of nature after a day’s walking, feeling quite emotional. It stirs my soul just thinking about it.

On my way home, I stopped at a creek I’m fond of, near a trailhead leading into the Bob Marshall Wilderness. The parking lot was empty of other cars or people. Last year when I’d camped there, the creek had held a delightful number of cylindrical caddisfly shells constructed from gravel about the size of a sesame seed. I looked for them but it was too late in the year.Source: Sometimes there’s a right answer, sometimes you sit by a creek, and sometimes they’re the same thing | On The CommonsThe creek ran cold across my bare feet, its sound and movement and chilly reminders of snowmelt all I really need in this world to ground myself in what’s real, and what matters. I sat there letting my feet go numb and the sound run through me, September’s late afternoon sunlight filtering through the aspen trees to glance off the water.

I don’t even know what to call that sound—a trickle, a ripple, a slow rush?

Sometimes the right answer is an action. Sometimes it’s a change in policy, or in culture. And sometimes it’s simply being, sitting there by a creek reminding yourself what it feels like to be alive, in a place you love. It’s asking questions of belonging and responsibility, and struggling with your own place in the world.

That sound is all of life to me. I could have sat there forever, grown cold and hungry, but I never for a moment would have felt alone.

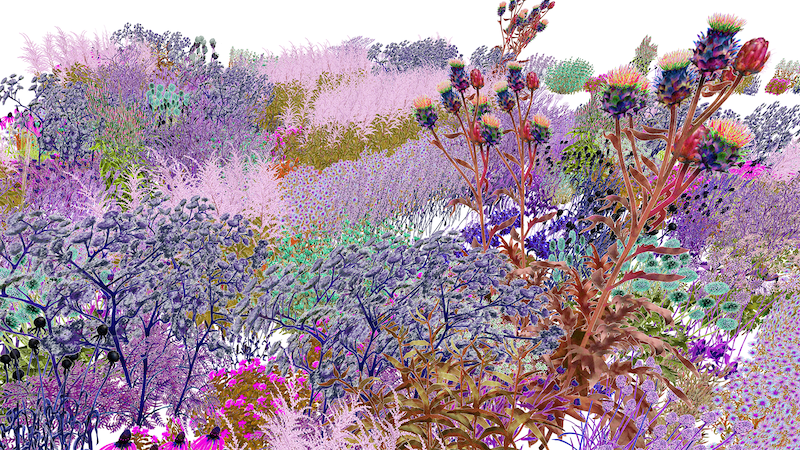

The world's largest climate-positive artwork provides food and nesting spots via algorithm

It’s interesting that this is being conceptualised as an ‘artwork’ rather than a technological intervention. Perhaps this is the way to deal with the climate crisis, by bringing algorithms from the cold, sterile environment of technology into the warmer, more joyful world of art?

This multidisciplinary project by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg explores the relationship between humans, nature, and technology and aims to draw attention to the importance of insects in pollination by creating an algorithmic solution for planting designs that serve a diverse range of pollinator species.

The project changes depending on location, debuting at the Eden Project in 2021 and includes 7,000 plants across 80 varieties. These provide food and nesting spots for insects with the aim to create the world’s largest climate-positive artwork.

This is not a natural ecosystem planted outside, there are plants from all over the world. With the expert group, we chose not to focus on native plants only because they are locally appropriate so they’re not invasive. So that’s the first thing—it’s an artificial landscape designed for nature, so it’s a very different way of creating an ecosystem. The other big challenge to the art world that I’m proposing is creating a climate-positive artwork. I also show in museums and I use digital media and that’s all very carbon-consuming. Here, we actually have an artwork fabricated in plants. It has its own climate impact because of the soil we’re moving, the plastic pots, the shipping of plants, but it’s here for at least three years, so it starts to outweigh that negative. There’s also a question of how we measure that, and that’s something I’m really interested in.Source: An Interview with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg | Berlin Art LinkThe other thing that’s really important to me is upending the idea of value. The art market is all about the one, the singular, the limited edition. This is an unlimited edition. The idea is: the more people who have one, the better each one is because each one supports the other. For me, that’s a strong statement to make to commissioners and when I’m trying to get more partners involved. It’s a very different way of thinking about how we create art and what its purpose is. For me, this is about playfulness, joy and celebrating nature. I call it an artwork and not a garden project because I think situating it in that context makes a powerful statement in itself.

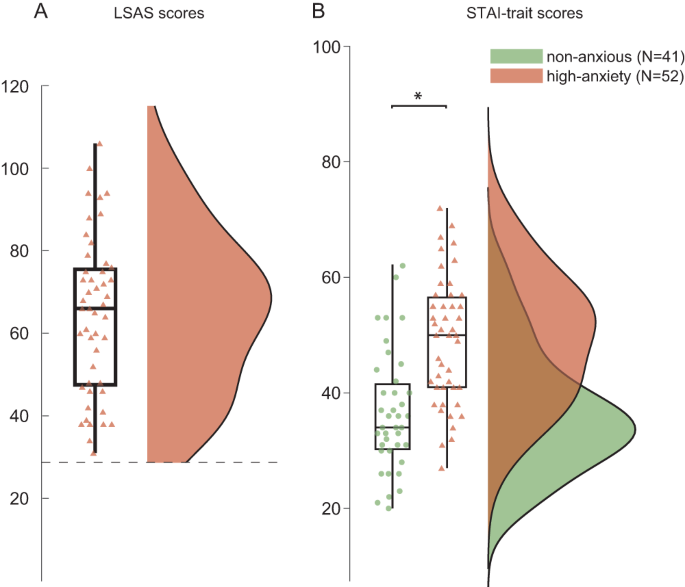

Why anxious people find it difficult to control their emotions

This explains a lot. Basically, studies have found that a specific part of the brain behaves differently in anxious individuals, and this difference might explain why they struggle with emotional control. It’s like a traffic jam in the brain that makes it harder for the signals to get through, leading to difficulties in managing emotional reactions.

Anxious individuals consistently fail in controlling emotional behavior, leading to excessive avoidance, a trait that prevents learning through exposure. Although the origin of this failure is unclear, one candidate system involves control of emotional actions, coordinated through lateral frontopolar cortex (FPl) via amygdala and sensorimotor connections. Using structural, functional, and neurochemical evidence, we show how FPl-based emotional action control fails in highly-anxious individuals. Their FPl is overexcitable, as indexed by GABA/glutamate ratio at rest, and receives stronger amygdalofugal projections than non-anxious male participants. Yet, high-anxious individuals fail to recruit FPl during emotional action control, relying instead on dorsolateral and medial prefrontal areas. This functional anatomical shift is proportional to FPl excitability and amygdalofugal projections strength. The findings characterize circuit-level vulnerabilities in anxious individuals, showing that even mild emotional challenges can saturate FPl neural range, leading to a neural bottleneck in the control of emotional action tendencies.Source: Anxious individuals shift emotion control from lateral frontal pole to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Nature Communications

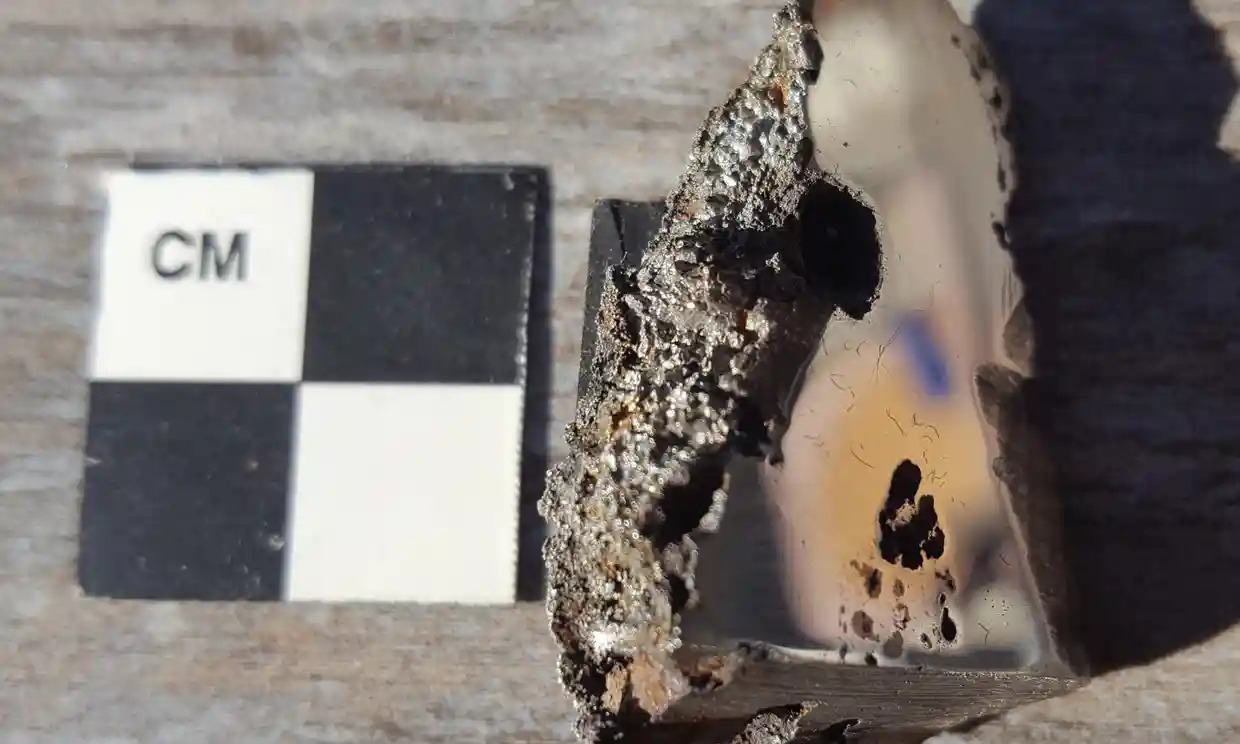

'Nightfall' meteorite contains new and unusual minerals

OK, so it’s not Vibranium, but discovering potentially three new minerals in a meteorite found in Somalia is pretty exciting! I wonder what new substances we’ll find as we further explore space, and what uses we’ll discover for them?

The meteorite, the ninth largest recorded at over 2 metres wide, was unearthed in Somalia in 2020, although local camel herders say it was well known to them for generations and named Nightfall in their songs and poems.Source: Researchers discover two new minerals on meteorite grounded in Somalia | The Guardian[…]

Dr Chris Herd, a professor in the department of earth and atmospheric sciences and the curator of the collection, said that while he was classifying the rock he noticed “unusual” minerals. Herd asked Andrew Locock, the head of the university’s electron microprobe laboratory, to investigate.

[…]

Similar minerals had been synthetically created in a lab in the 1980s but never recorded as appearing in nature, Herd said, adding that these new minerals could help understand how “nature’s laboratory” works and may have as yet unknown real-world uses. A third potentially new mineral is being analysed.

The mesmerising murmurations of Europe’s starlings

Incredible. I highly recommend clicking through to watch the videos!

How the birds move together in such close proximity, as though one organism, is another mystery. One study found that each starling was responding instantly to the six or seven birds closest to it to maintain group cohesion.Source: ‘A fragment of eternity’: the mesmerising murmurations of Europe’s starlings | The Guardian

The cost of a thing is the amount of life which is required to be exchanged for it

This article in The Atlantic by Alan Lightman points out how biophilic we have been historically as a species, and how that’s changed only recently.

None of this, of course, helps with the climate emergency and the concomitant biodiversity collapse. I read the WEF Global Risks Report for 2022 and, well, I’ve read more hopeful documents.

Most of the minutes and hours of each day we spend in temperature-controlled structures of wood, concrete, and steel. With all of its success, our technology has greatly diminished our direct experience with nature. We live mediated lives. We have created a natureless world.Source: This Is No Way to Be Human - The AtlanticIt was not always this way. For more than 99 percent of our history as humans, we lived close to nature. We lived in the open. The first house with a roof appeared only 5,000 years ago. Television less than a century ago. Internet-connected phones only about 30 years ago. Over the large majority of our 2-million-year evolutionary history, Darwinian forces molded our brains to find kinship with nature, what the biologist E. O. Wilson called “biophilia.” That kinship had survival benefit. Habitat selection, foraging for food, reading the signs of upcoming storms all would have favored a deep affinity with nature. Social psychologists have documented that such sensitivities are still present in our psyches today. Further psychological and physiological studies have shown that more time spent in nature increases happiness and well-being; less time increases stress and anxiety. Thus, there is a profound disconnect between the natureless environment we have created and the “natural” affections of our minds. In effect, we live in two worlds: a world in close contact with nature, buried deep in our ancestral brains, and a natureless world of the digital screen and constructed environment, fashioned from our technology and intellectual achievements. We are at war with our ancestral selves. The cost of this war is only now becoming apparent.

[…]

I am not so naive as to think that the careening technologization of the modern world will stop or even slow down. But I do think that we need to be more mindful of what this technology has cost us and the vital importance of direct experiences with nature. And by “cost,” I mean what Henry David Thoreau meant in Walden: “The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” The new technology in Thoreau’s day was the railroad, which he feared was overtaking life. Thoreau’s concern was updated by the literary critic and historian of technology Leo Marx in his 1964 book, The Machine in the Garden. That book describes the way in which pastoral life in America was interrupted by the technology and industrialization of the 19th and 20th centuries. Marx could not have imagined the internet and the smartphone, which arrived only a few decades later. And now I worry about the promise of an all-encompassing virtual world called the “metaverse,” and the Silicon Valley arms race to build it. Again, it is not the technology itself that should concern us. It is how we use that technology, in balance with the rest of our lives.

Fractional dosing of COVID vaccines may help more people get immunity faster

The advice to date has, quite rightly, to get any COVID vaccine that’s available to you. For me, that’s meant a double dose of AstraZeneca, and I’m happy about that.

But as the pandemic progresses, we need to be aware that some vaccines are more effective than others. This working paper, building on one published in Nature earlier this year, looks at how ‘fractional dosing’ of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines could reach more people more quickly.

Needless to say, we shouldn’t be in the position where people in less developed countries are getting access to vaccines much more slowly than the rest of the world. But, pragmatically speaking, this may help.

We supplement the key figure from Khoury et al.’s paper to show that fractional doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have neutralizing antibody levels (as measured in the early phase I and phase II trials) that look to be on par with those of many approved vaccines. Indeed, a one-half or one-quarter dose of the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine is predicted to be more effective than the standard dose of some of the other vaccines like the AstraZeneca, J&J or Sinopharm vaccines, assuming the same relationship as in Khoury et al. holds. The point is not that these other vaccines aren’t good–they are great! The point is that by using fractional dosing we could rapidly and safely expand the number of effective doses of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines.Source: A Half Dose of Moderna is More Effective Than a Full Dose of AstraZeneca | Marginal REVOLUTION[…]

One more point worth mentioning. Dose stretching policies everywhere are especially beneficial for less-developed countries, many of which are at the back of the vaccine queue. If dose-stretching cuts the time to be vaccinated in half, for example, then that may mean cutting the time to be vaccinated from two months to one month in a developed country but cutting it from two years to one year in a country that is currently at the back of the queue.

Who's the pet? Tarantula or tiny frog?

I read recently that some tarantulas keep tiny frogs as ‘pets’. Of course, I had to do some more digging and found out that’s not quite true, and if it were, it would be more like the other way around (as some tarantulas are so docile!)

I’ve seen some “sources” (and I really do use the word source here in it’s least possible capacity) try to say that the frogs eat potential nuisances to the spider like ants, mites and other nasties which is why the spider keeps it around. This is silly for a few reasons. 1. Tarantulas line the entire length of their burrow (which can be several feet deep) with thick sticky web. This prevents things like small insects from burrowing into or walking into their homes. Anything large enough to do so is too big to be eaten by the frog. 2. These frogs don’t even eat stuff like mites or springtails. The prey items are far too small for them to bother with. 3. If there are enough ants to bother a tarantula of this size the frog is going to die if it sticks around anyway.Source: Is it true that some tarantulas keep tiny frogs as pets? - Quora

In a dark place

Last year, I remember being amazed by how black a new substance was that’s been created by scientists. Called Vantablack, it’s like a black hole for light:

Vantablack is genuinely amazing: It’s so good at absorbing light that if you move a laser onto it, the red dot disappears.

However, it turns out that Mother Nature already had that trick up her sleeve. Birds of Paradise have a similar ability:

A typical bird feather has a central shaft called a rachis. Thin branches, or barbs, sprout from the rachis, and even thinner branches—barbules—sprout from the barbs. The whole arrangement is flat, with the rachis, barbs, and barbules all lying on the same plane. The super-black feathers of birds of paradise, meanwhile, look very different. Their barbules, instead of lying flat, curve upward. And instead of being smooth cylinders, they are studded in minuscule spikes. “It’s hard to describe,” says McCoy. “It’s like a little bottle brush or a piece of coral.”These unique structures excel at capturing light. When light hits a normal feather, it finds a series of horizontal surfaces, and can easily bounce off. But when light hits a super-black feather, it finds a tangled mess of mostly vertical surfaces. Instead of being reflected away, it bounces repeatedly between the barbules and their spikes. With each bounce, a little more of it gets absorbed. Light loses itself within the feathers.

Incredible.

Source: The Atlantic