- Is High Quality Software Worth the Cost? (Martin Fowler) — "I thus divide software quality attributes into external (such as the UI and defects) and internal (architecture). The distinction is that users and customers can see what makes a software product have high external quality, but cannot tell the difference between higher or lower internal quality."

- What the internet knows about you (Axios) — "The big picture: Finding personal information online is relatively easy; removing all of it is nearly impossible."

- Against Waldenponding II (ribbonfarm) — "Waldenponding is a search for meaning that is circumscribed by the what you might call the spiritual gravity field of an object or behavior held up as ineffably sacred. "

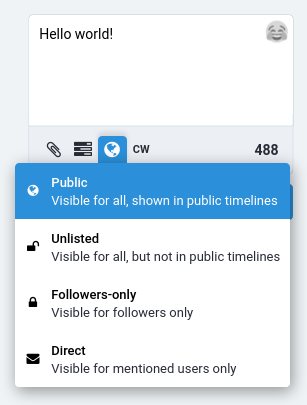

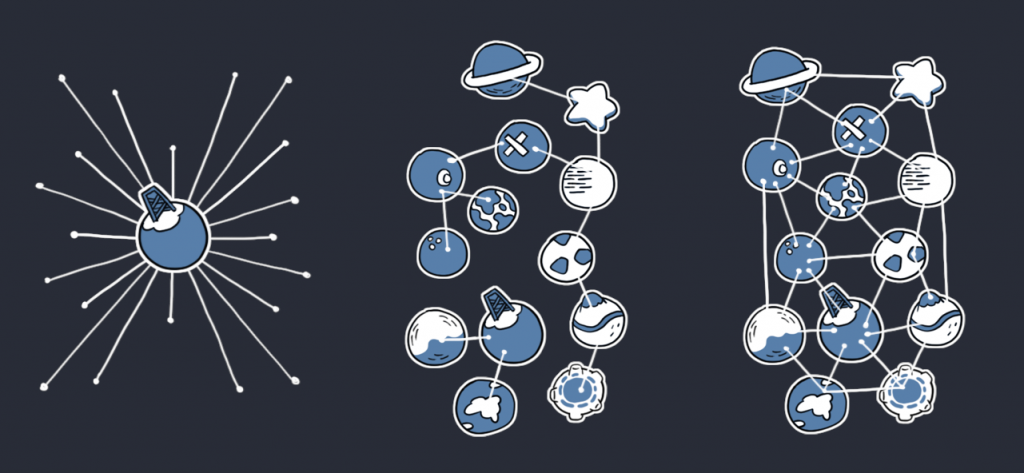

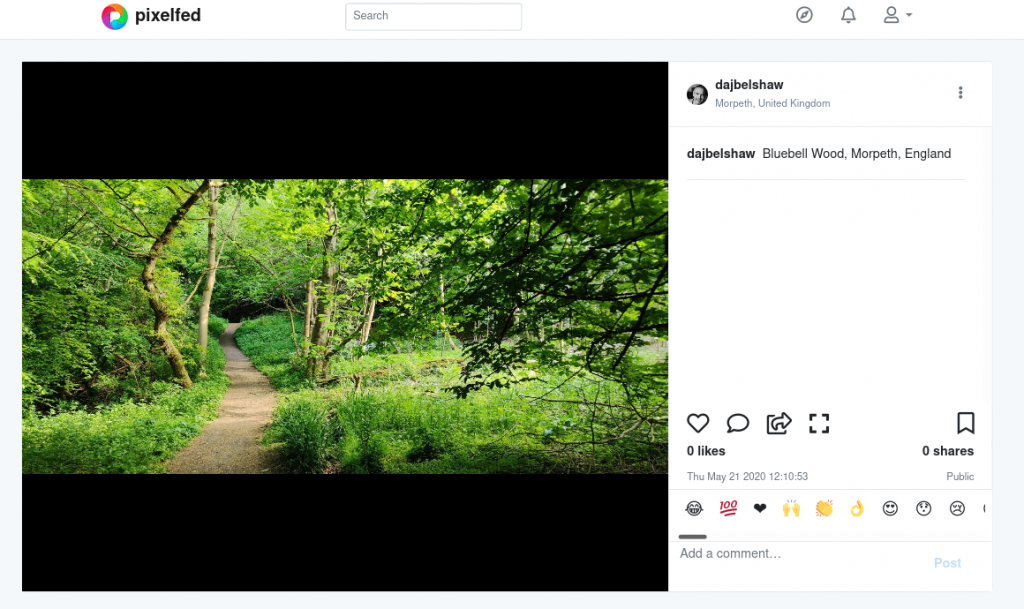

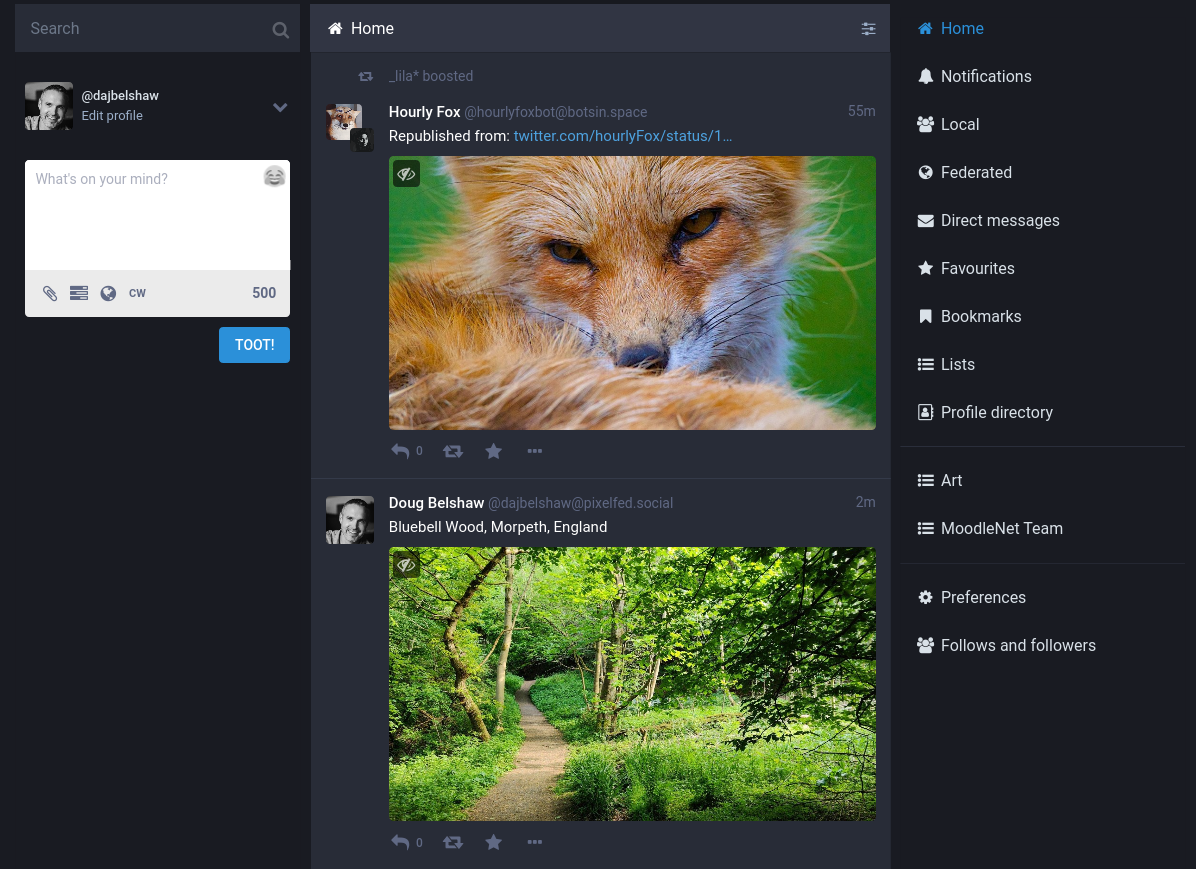

Microcast #081 - Anarchy, Federation, and the IndieWeb

Happy New Year! It's good to be back.

This week's microcast answers a question from John Johnston about federation and the IndieWeb. I also discuss anarchism and left-libertarianism, for good measure.

Show notes

Do not impose one's own standard on the work of others. Mutual moderation and cooperation will proffer better results.

I think I must have come across the above saying from Hsing Yun via Mayel de Borniol. It captures some of what I want to discuss in this article which centres around decision-making within organisations.

Let's start with a great article from Roman Imankulov from Doist. He looks to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)'s approach, as enshrined in a document from 2014, explaining their 'rough consensus' approach:

Rough consensus isn’t majority rule. It’s okay to go ahead with a solution that may not look like the best choice for everyone or even the majority. "Not the best choice" means that you believe there is a better way to solve the problem, but you accept that this one will work too. That type of feedback should be welcomed, but it shouldn’t be allowed to slow down a decision.

Roman Imankulov

If they try hard enough, everyone can come up with a reason why an idea or approach won't work. My experience is that many middle-aged white men see it as their sworn duty to come up with as many of those reasons as possible 🙄

What the IETF calls 'rough consensus' I think I'd probably call 'alignment'. You don't all have to agree that a proposal is without problems, but those problems should be surmountable. Within CoTech, a network of co-operatives to which We Are Open belongs, we use Loomio. It has a number of decision tools, including the 'proposal':

As you can see, there's the ability for anyone to 'Block' a proposal, meaning that it can't be passed in its current form. People can 'Abstain' if there's a conflict of interest, or if they don't feel like they've got enough experience or expertise. Note that it's entirely possible for someone to 'Disagree' and the motion to still go ahead.

What I like about Loomio is a tool is that it focuses on decision-making. It's not about endless discussion and debate, but about having a bias towards action. You can separate the planning process from the implementation stage:

Rough consensus doesn’t mean that we don’t aim for perfection in the actual implementation of the solution. When implementing, we should always aim for technical excellence. Commitment to the implementation is often what makes a solution the right one. (This is similar to Amazon’s "disagree and commitment" philosophy.)

Roman Imankulov

I can't, by my nature, stand hierarchy. Unfortunately, it's the default operating system of most organisations, and despite our best efforts, we haven't got a one-size-fits-all alternative to it. I think this is partly because nobody has to teach you how hierarchy works.

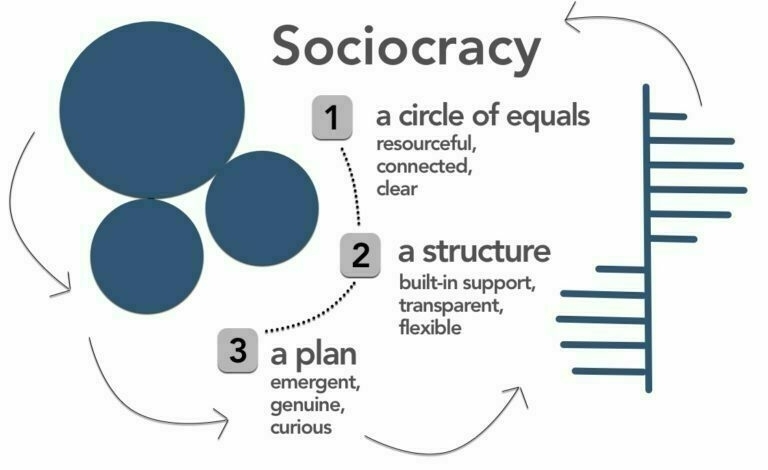

Over the weekend, while we were walking in the Lake District, Tom Broughton and I were discussing sociocracy:

Sociocracy, also known as dynamic governance, is a system of governance which seeks to achieve solutions that create harmonious social environments as well as productive organizations and businesses. It is distinguished by the use of consent rather than majority voting in decision-making, and decision-making after discussion by people who know each other.

Wikipedia

Tom's a Quaker and so used to consent-based decision-making. I explained that we'd asked Outlandish (a CoTech member) to run a sociocratic design sprint to kick off our work around MoodleNet. It was based on the Google design sprint approach, but — as Kayleigh from Outlandish points out — featured an important twist:

We decided to remove the ‘decider’ role that a Google Sprint employs. We weren’t comfortable with the responsibility and authority of decisions sitting with one person, and having spent a few years practising sociocracy already, it just wouldn’t have felt right.

[...]

Martin, Moodle’s CEO and founder joined us for the duration of the sprint. While Martin naturally had the most expertise in the domain, the most ‘skin in the game’ and the had done the most background thinking sociocracy meant that he still needed to convince the rest of the sprint team as to why his ideas were best, and take on board other suggestions and compromises. We feel that it led to better outputs at each stage of the design sprint.

Kayleigh Walsh

It was the first time I'd seen a CEO give up their hierarchical power in the interests of ensuring that we designed something that could be the best it could possibly be. In fact, that week last May is probably one of the highlights of my career to date.

That was one week into which was poured a lot of time, attention, and money. But what if you want to practise something like sociocracy on a day-to-day basis? You have to think about structure of organisations, as there's no such thing as 'structureless' group:

Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved. The very fact that we are individuals, with different talents, predispositions, and backgrounds makes this inevitable. Only if we refused to relate or interact on any basis whatsoever could we approximate structurelessness -- and that is not the nature of a human group.

Jo Freeman

It's only within the last year that I've discovered left-libertarianism as a coherent political and social philosophy that helps me reconcile two things that I've previously found difficult. On the one hand, I believe in a small state. On the other, I believe we have a duty to one another and should help out wherever possible.

Left-libertarianism, also known as left-wing libertarianism, names several related yet distinct approaches to political and social theory which stress both individual freedom and social equality. In its classical usage, left-libertarianism is a synonym for anti-authoritarian varieties of left-wing politics such as libertarian socialism which includes anarchism and libertarian Marxism among others.

[...]

While maintaining full respect for personal property, left-libertarians are skeptical of or fully against private ownership of natural resources, arguing in contrast to right-libertarians that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights and maintain that natural resources (raw land, oil, gold, the electromagnetic spectrum, air-space and so on) should be held in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively. Those left-libertarians who support private property do so under occupation and use property norms or under the condition that recompense is offered to the local or even global community.

Wikipedia

In other words, you don't have to be a Marxist, communist, or anarchist to be a left-libertarian. It means you can start from a basis of personal autonomy, but end with an egalitarian approach to the world where resources (especially natural resources) are collectively owned.

To me, this is the position from which we should start when we think about decision-making within organisations. First of all, we should ask: who owns the organisation? Why? Second, we should consider how the organisation should be structured. Ten layers of management might be bad, but so is a completely flat structure for 700 people. And finally, we should think about appropriate mechanisms for decision-making.

The usual criticisms of sociocracy and other consent-based decision-making systems is that they are too slow, that they don't work in practice. In my experience, by participating in the Outlandish/Moodle design sprint, witnessing a Mozilla Festival session in which participants quickly got up-to-speed on sociocracy, and through CoTech gatherings (both online and offline), I'd say sociocracy is a viable solution.

The best decisions aren't ones where you have all of the information to hand. That's impossible. The best decisions are based on trust and consent.

As I get older, I'm realising that the best way we can improve the world is to improve its governance. It's not that we haven't got extremely talented people in the world, it's that we don't always know how to make good decision. I'd like to change that.

What is no good for the hive is no good for the bee

So said Roman Emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius. In this article, I want to apply that to our use of technology as well as the stories we tell one another about that technology use.

Let's start with an excellent post by Nolan Lawson, who when I started using Twitter less actually deleted his account and went all-in on the Fediverse. He maintains a Mastodon web client called Pinafore, and is a clear-headed thinker on all things open. The post is called Tech veganism and sums up the problem I have with holier-than-thou open advocates:

I find that there’s a bit of a “let them eat cake” attitude among tech vegan boosters, because they often discount the sheer difficulty of all this stuff. (“Let them use Linux” could be a fitting refrain.) After all, they figured it out, so why can’t you? What, doesn’t everyone have a computer science degree and six years experience as a sysadmin?

To be a vegan, all you have to do is stop eating animal products. To be a tech vegan, you have to join an elite guild of tech wizards and master their secret arts. And even then, you’re probably sneaking a forbidden bite of Google or Apple every now and then.

Nolan Lawson

It's that second paragraph that's the killer for me. I'm pescetarian and probably about the equivalent of that, in Lawson's lingo, when it comes to my tech choices. I definitely agree with him that the conversation is already changing away from open source and free software to what Mark Zuckerberg (shudder) calls "time well spent":

I also suspect that tech veganism will begin to shift, if it hasn’t already. I think the focus will become less about open source vs closed source (the battle of the last decade) and more about digital well-being, especially in regards to privacy, addiction, and safety. So in this way, it may be less about switching from Windows to Linux and more about switching from Android to iOS, or from Facebook to more private channels like Discord and WhatsApp.

Nolan Lawson

This is reminiscent of Yancey Strickler's notion of 'dark forests'. I can definitely see more call for nuance around private and public spaces.

So much of this, though, depends on your worldview. Everyone likes the idea of 'freedom', but are we talking about 'freedom from' or 'freedom to'? How important are different types of freedom? Should all information be available to everyone? Where do rights start and responsibilities stop (and vice-versa)?

One thing I've found fascinating is how the world changes and debates get left behind. For example, the idea (and importance) of Linux on the desktop has been something that people have been discussing most of my adult life. At the same time, cloud computing has changed the game, with a lot of the data processing and heavy lifting being done by servers — most of which are powered by Linux!

Mark Shuttleworth, CEO of Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu Linux, said in a recent interview:

I think the bigger challenge has been that we haven't invented anything in the Linux that was like deeply, powerfully ahead of its time... if in the free software community we only allow ourselves to talk about things that look like something that already exists, then we're sort of defining ourselves as a series of forks and fragmentations.

Mark Shuttleworth

This is a problem that's wider than just software. Those of us who are left-leaning are more likely to let small ideological differences dilute our combined power. That affects everything from opposing Brexit, to getting people to switch to Linux. There's just too much noise, too many competing options.

Meanwhile, as the P2P Foundation notes, businesses swoop in and use open licenses to enclose the Commons:

[I]t is clear that these Commons have become an essential infrastructure without which the Internet could no longer function today (90% of the world’s servers run on Linux, 25% of websites use WordPress, etc.) But many of these projects suffer from maintenance and financing problems, because their development depends on communities whose means are unrelated to the size of the resources they make available to the whole world.

[...]

This situation corresponds to a form of tragedy of the Commons, but of a different nature from that which can strike material resources. Indeed, intangible resources, such as software or data, cannot by definition be over-exploited and they even increase in value as they are used more and more. But tragedy can strike the communities that participate in the development and maintenance of these digital commons. When the core of individual contributors shrinks and their strengths are exhausted, information resources lose quality and can eventually wither away.

P2P Foundation

So what should we do? One thing we've done with MoodleNet is to ensure that it has an AGPL license, one that Google really doesn't like. They state perfectly the reasons why we selected it:

The primary risk presented by AGPL is that any product or service that depends on AGPL-licensed code, or includes anything copied or derived from AGPL-licensed code, may be subject to the virality of the AGPL license. This viral effect requires that the complete corresponding source code of the product or service be released to the world under the AGPL license. This is triggered if the product or service can be accessed over a remote network interface, so it does not even require that the product or service is actually distributed.

Google

So, in other words, if you run a server with AGPL code, or create a project with source code derived from it, you must make that code available to others. To me, it has the same 'viral effect' as the Creative Commons BY-SA license.

As Benjamin "Mako" Hill points out in a recent keynote, we need to be a bit more wise when it comes to 'choosing a side'. Cory Doctorow, summarising Mako's keynote says:

[M]arkets discovered free software and turned it into "open source," figuring out how to create developer communities around software ("digital sharecropping") that lowered their costs and increased their quality. Then the companies used patents and DRM and restrictive terms of service to prevent users from having any freedom.

Mako says that this is usually termed "strategic openness," in which companies take a process that would, by default, be closed, and open the parts of it that make strategic sense for the firm. But really, this is "strategic closedness" -- projects that are born open are strategically enclosed by companies to allow them to harvest the bulk of the value created by these once-free systems.

[...]

Mako suggests that the time in which free software and open source could be uneasy bedfellows is over. Companies' perfection of digital sharecropping means that when they contribute to "free" projects, all the freedom will go to them, not the public.

Cory Doctorow

It's certainly an interesting time we live in, when the people who are pointing out all of the problems (the 'tech vegans') are seen as the problem, and the VC-backed companies as the disruptive champions of the people. Tech follows politics, though, I guess.

Also check out: