Signalling that you're AFK in a world where you can never really be AFK

I used AIM and MSN Messenger as a teenager, from around 1996 to about 2001. It was great, and I remember messaging with friends and the woman who is now my wife using it.

Part of the whole experience of it was that you were using the service on a shared device, a computer that the rest of the family would use. In that sense, it was more like a text-based landline phone. It wasn’t personal like the smart devices that live in our pockets these days.

There a lot of nostalgia about how things used to be, and we’re certainly not going back to shared devices as a primary means of getting online anytime soon. So that means that we need other ways of respecting one another’s boundaries. This is something we can actually reclaim ourselves by responding to messages on our own terms.

Sometimes you had to step away. So you threw up an Away Message: I’m not here. I’m in class/at the game/my dad needs to use the comp. I’ve left you with an emo quote that demonstrates how deep I am. Or, here’s a song lyric that signals I am so over you. Never mind that my Away Message is aimed at you.Source: It's Time to Bring Back the AIM Away Message | WIREDI miss Away Messages. This nostalgia is layered in abstraction; I probably miss the newness of the internet of the 1990s, and I also miss just being … away. But this is about Away Messages themselves—the bits of code that constructed Maginot Lines around our availability. An Away Message was a text box full of possibilities, a mini-MySpace profile or a Facebook status update years before either existed. It was also a boundary: An Away Message not only popped up as a response after someone IM’d you, it was wholly visible to that person b they IM’d you.

Nothing like this exists in our modern messaging apps.

[…]

People send too many messages. I send too many messages. The first step in making messaging amends is to admit that you, too, are an inconsiderate messaging maniac.

But I’ll never stop, and neither will you. Quick messaging is a utility. It is, in many cases, the most efficient and meaningful form of communication we have. It’s crucial for relationship building, for organizing, for supporting others through hard times. It can be joyful.

[…]

Would something like the Away Message, a relic from an era when we just didn’t message so darn much, actually put up the guardrails we need? Maybe not. But I’m willing to try anything at this point. If we can’t ever get away from messages, at the very least we can create a digital simulacrum of ourselves that appears to be away. What else is the internet for?

How long before everyone's using decentralised messengers?

I first experimented with Linux in 1997. It wasn't until 20 years later that I was running it as my default operating system.

I hope it doesn't take as long for something like Briar to be my default messaging app! It's difficult to make the case for it when everyone's got WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, or the like.

But the radical, decentralised, approach to privacy that Briar takes is refreshing.

Another potential use case scenario for Briar are natural disasters. With the climate crisis getting worse day by day, destruction of critical infrastructure is a problem affecting more and more parts of the world, as the recent floods in Europe and China and the wildfires all around the world have shown.

While Briar can definitively be useful in those situations, its trade-offs in favor of privacy are severely limiting its connectivity capabilities. To make an example, imagine your city just got nearly extinguished by a wildfire, destroying all the telecommunications infrastructure that was once there. Fortunately, you and your friends got Briar installed, so when a friend of you drops by you grasp at the chance and write messages to all your friends in-town. One could think that all those messages get synchronized to your friend’s device, so she can serve as a carrier for your other friends' messages. Unfortunately, that’s not how Briar works.

As I’ve outlined before, metadata protection is one of Briar’s primary goals. Therefore, Briar doesn’t synchronize messages to your friend Alice with Bob when you meet him in order to not let Bob know that you’re communicating with Alice. This is very useful when you can’t trust even your contacts not to be spying on you, but it’s most likely a huge problem when connectivity is all you want in the face of natural disasters.

This message routing scheme used by Briar is called “single-hop social mesh” because you only ever send messages to your contacts if you have a direct connection to them. During catastrophes you most likely want to have at least “multi-hop social mesh” or yet even better “public mesh” where you share messages not only with your contacts but with anybody using Briar. However, as connectivity improves, privacy gets worse because people will know when you’re communicating with whom.

The good news are that Briar is currently receiving funding to conduct research on supporting other types of mesh. Still it will take a lot of time until something gets implemented in Briar, so all of this should be considered long-term perspectives. Note, though, that this mainly affects private chats and private groups. If you and all your friends are part of a forum (Briar’s “public” version of group chats), Alice will indeed serve as a carrier for your messages sent to that forum.

Using WhatsApp is a (poor) choice that you make

People often ask me about my stance on Facebook products. They can understand that I don't use Facebook itself, but what about Instagram? And surely I use WhatsApp? Nope.

Given that I don't usually have a single place to point people who want to read about the problems with WhatsApp, I thought I'd create one.

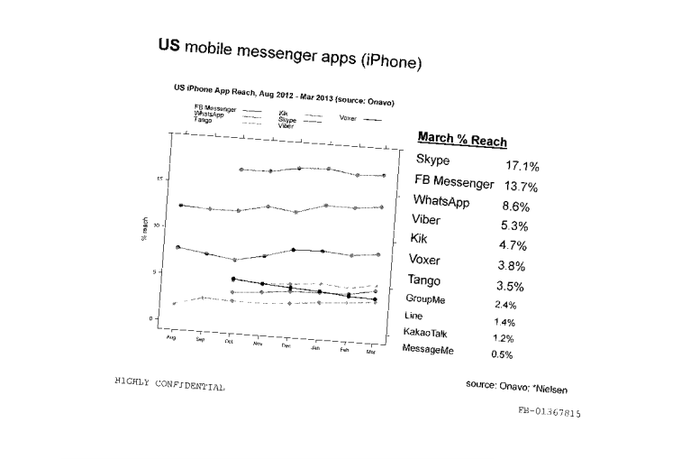

WhatsApp is a messaging app that was acquired by Facebook for the eye-watering amount of $19 billion in 2014. Interestingly, a BuzzFeed News article from 2018 cites documents confidential documents from the time leading up to the acquisition that were acquired by the UK's Department for Culture, Media, and Sport. They show the threat WhatsApp posed to Facebook at the time.

As you can see from the above chart, Facebook executives were shown in 2013 that WhatsApp (8.6% reach) was growing rapidly and posed a huge threat to Facebook Messenger (13.7% reach).

So Facebook bought WhatsApp. But what did they buy? If, as we're led to believe, WhatsApp is 'end-to-end encrypted' then Facebook don't have access to the messages of users. So what's so valuable?

Brian Acton, one of the founders of WhatsApp (and a man who got very rich through its sale) has gone on record saying that he feels like he sold his users' privacy to Facebook.

Facebook, Acton says, had decided to pursue two ways of making money from WhatsApp. First, by showing targeted ads in WhatsApp’s new Status feature, which Acton felt broke a social compact with its users. “Targeted advertising is what makes me unhappy,” he says. His motto at WhatsApp had been “No ads, no games, no gimmicks”—a direct contrast with a parent company that derived 98% of its revenue from advertising. Another motto had been “Take the time to get it right,” a stark contrast to “Move fast and break things.”

Facebook also wanted to sell businesses tools to chat with WhatsApp users. Once businesses were on board, Facebook hoped to sell them analytics tools, too. The challenge was WhatsApp’s watertight end-to-end encryption, which stopped both WhatsApp and Facebook from reading messages. While Facebook didn’t plan to break the encryption, Acton says, its managers did question and “probe” ways to offer businesses analytical insights on WhatsApp users in an encrypted environment.

Parmy Olson (Forbes)

The other way Facebook wanted to make money was to sell tools to businesses allowing them to chat with WhatsApp users. These tools would also give "analytical insights" on how users interacted with WhatsApp.

Facebook was allowed to acquire WhatsApp (and Instagram) despite fears around monopolistic practices. This was because they made a promise not to combine data from various platforms. But, guess what happened next?

In 2014, Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19b, and promised users that it wouldn't harvest their data and mix it with the surveillance troves it got from Facebook and Instagram. It lied. Years later, Facebook mixes data from all of its properties, mining it for data that ultimately helps advertisers, political campaigns and fraudsters find prospects for whatever they're peddling. Today, Facebook is in the process of acquiring Giphy, and while Giphy currently doesn’t track users when they embed GIFs in messages, Facebook could start doing that anytime.

Cory Doctorow (EFF)

So Facebook is harvesting metadata from its various platforms, tracking people around the web (even if they don't have an account), and buying up data about offline activities.

All of this creates a profile. So yes, because of end-ot-end encryption, Facebook might not know the exact details of your messages. But they know that you've started messaging a particular user account around midnight every night. They know that you've started interacting with a bunch of stuff around anxiety. They know how the people you message most tend to vote.

Do I have to connect the dots here? This is a company that sells targeted adverts, the kind of adverts that can influence the outcome of elections. Of course, Facebook will never admit that its platforms are the problem, it's always the responsibility of the user to be 'vigilant'.

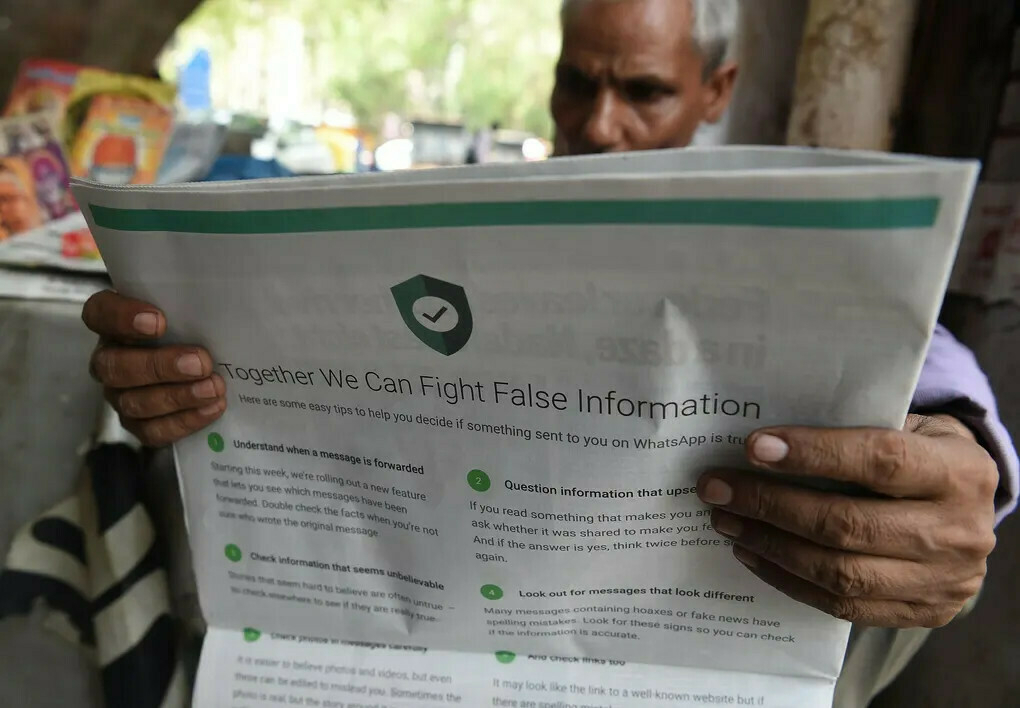

So you might think that you're just messaging your friend or colleague on a platform that 'everyone' uses. But your decision to go with the flow has consequences. It has implications for democracy. It has implications on creating a de facto monopoly for our digital information. And it has implications around the dissemination of false information.

The features that would later allow WhatsApp to become a conduit for conspiracy theory and political conflict were ones never integral to SMS, and have more in common with email: the creation of groups and the ability to forward messages. The ability to forward messages from one group to another – recently limited in response to Covid-19-related misinformation – makes for a potent informational weapon. Groups were initially limited in size to 100 people, but this was later increased to 256. That’s small enough to feel exclusive, but if 256 people forward a message on to another 256 people, 65,536 will have received it.

[...]

A communication medium that connects groups of up to 256 people, without any public visibility, operating via the phones in their pockets, is by its very nature, well-suited to supporting secrecy. Obviously not every group chat counts as a “conspiracy”. But it makes the question of how society coheres, who is associated with whom, into a matter of speculation – something that involves a trace of conspiracy theory. In that sense, WhatsApp is not just a channel for the circulation of conspiracy theories, but offers content for them as well. The medium is the message.

William Davies (The Guardian)

I cannot control the decisions others make, nor have I forced my opinions on my two children, who (despite my warnings) both use WhatsApp to message their friends. But, for me, the risk to myself and society of using WhatsApp is not one I'm happy with taking.

Just don't say I didn't warn you.

Header image by Rachit Tank